Michael Franti Isnot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyrics and the Law : the Constitution of Law in Music

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2006 Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music. Aaron R. S., Lorenz University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Lorenz, Aaron R. S.,, "Lyrics and the law : the constitution of law in music." (2006). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2399. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2399 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2006 Department of Political Science © Copyright by Aaron R.S. Lorenz 2006 All Rights Reserved LYRICS AND THE LAW: THE CONSTITUTION OF LAW IN MUSIC A Dissertation Presented by AARON R.S. LORENZ Approved as to style and content by: Sheldon Goldman, Member DEDICATION To Martin and Malcolm, Bob and Peter. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project has been a culmination of many years of guidance and assistance by friends, family, and colleagues. I owe great thanks to many academics in both the Political Science and Legal Studies fields. Graduate students in Political Science have helped me develop a deeper understanding of public law and made valuable comments on various parts of this work. -

Jazz Festival Pr

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! DC Jazz Festival Neighborhood Venues Host More Than 80 Performances Citywide Jazz in the ‘Hoods, a major feature of the DC Jazz Festival, annually attracts a vibrant audience of thousands of music enthusiasts and highlights the city as a vibrant cultural capital by bringing jazz to all four quadrants of the nation’s capital, with over 80 performances at more than !40 neighborhood venues. View full schedule. !RAMW Member Jazz Festival Venues & Specials: Carmine’s DC 425 7th Street NW Washington, DC 20004 (202) 737-7770 http://www.carminesnyc.com !Special: Groups of 6 or more, show your ticket stub to receive a free desert. Bistrot Lepic & Wine Bar 1736 Wisconsin Ave NW Washington, DC 20007 (202) 333-0111 !http://www.bistrotlepic.com !June 10th & 15th- Jazz in the ‘Hoods Presents: Jazz in the Wine Room (7:00 pm) Acadiana 901 New York Ave NW Washington, DC 20001 (202) 408-8848 !http://www.acadianarestaurant.com/acadiana.html !June 14th - Jazz in the ‘Hoods Presents: Live Jazz Brunch (11:00 am) ! ! The Hamilton Live 600 14th St NW Washington, DC 20005 (202) 787-1000 !http://www.thehamiltondc.com June 10th - John Scofield ÜberJam Band featuring Andy Hess, Avi Bortnick & Tony !Mason: 7:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) June 11th - Paquito D’Rivera with Special Guest Edmar Castañeda: 7:30 pm (Doors !open at 6:30 pm) June 12th - The Bad plus Joshua Redman with Opener Underwater Ghost featuring !Allison Miller: 8:30 pm (Doors open at 7 pm) June 13th - (Early and Late Shows) Jack DeJohnette Trio featuring Ravi Coltrane & Matthew Garrison: 7:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) & 10:30 pm (Doors open at 9:30 !pm) June 14th - Stanton Moore Trio & Charlie Hunter Trio featuring Bobby Previte & Curtis !Fowlkes: 7:30 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) !June 15th - An Evening with Snarky Puppy (First Night): 8 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm) June 16th - An Evening with Snarky Puppy (Second Night): 8 pm (Doors open at 6:30 pm). -

Eddie B's Wedding Songs

ƒƒƒƒƒƒ ƒƒƒƒƒƒ Eddie B. & Company Presents Music For… Bridal Party Introductions Cake Cutting 1. Beautiful Day . U2 1. 1,2,3,4 (I Love You) . Plain White T’s 2. Best Day Of My Life . American Authors 2. Accidentally In Love . Counting Crows 3. Bring Em’Out . T.I. 3. Ain’t That A Kick In The Head . Dean Martin 4. Calabria . Enur & Natasja 4. All You Need Is Love . Beatles 5. Celebration . Kool & The Gang 5. Beautiful Day . U2 6. Chelsea Dagger . Fratellis 6. Better Together . Jack Johnson 7. Crazy In Love . Beyonce & Jay Z 7. Build Me Up Buttercup . Foundations 8. Don’t Stop The Party . Pitbull 8. Candyman . Christina Aguilera 9. Enter Sandman . Metalica 9. Chapel of Love . Dixie Cups 10. ESPN Jock Jams . Various Artists 10. Cut The Cake . Average White Bank 11. Everlasting Love . Carl Carlton 11. Everlasting Love . Carl Carlton & Gloria Estefan 12. Eye Of The Tiger . Survivor 12. Everything . Michael Buble 13. Feel So Close . Calvin Harris 13. Grow Old With You . Adam Sandler 14. Feel This Moment . Pitt Bull & Christina Aguilera 14. Happy Together . Turtles 15. Finally . Ce Ce Peniston 15. Hit Me With Your Best Shot . Pat Benatar 16. Forever . Chris Brown 16. Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You) . James Taylor 17. Get Ready For This . 2 Unlimited 17. I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) Four Tops 18. Get The Party Started . Pink 18. I Got You Babe . Sonny & Cher 19. Give Me Everything Tonight . Pitbull & Ne-Yo 19. Ice Cream . Sarah McLachlan 20. Gonna Fly Now . -

I S C O R D E R Free

I S C O R D E R FREE IUTE K OGWAI ARHEAD NC HR IS1 © "DiSCORDER" 2001 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circuldtion 1 7,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance, to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN elsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money orders payable to DiSCORDER Mag azine. DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the August issue is July 14th. Ad space is available until July 21st and ccn be booked by calling Maren at 604.822.3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. DiS CORDER is not responsible for loss, damage, or any other injury to unsolicited mcnuscripts, unsolicit ed drtwork (including but not limited to drawings, photographs and transparencies), or any other unsolicited material. Material can be submitted on disc or in type. As always, English is preferred. Send e-mail to DSCORDER at [email protected]. From UBC to Langley and Squamish to Bellingham, CiTR can be heard at 101.9 fM as well as through all major cable systems in the Lower Mainland, except Shaw in White Rock. Call the CiTR DJ line at 822.2487, our office at 822.301 7 ext. 0, or our news and sports lines at 822.3017 ext. 2. Fax us at 822.9364, e-mail us at: [email protected], visit our web site at http://www.ams.ubc.ca/media/citr or just pick up a goddamn pen and write #233-6138 SUB Blvd., Vancouver, BC. -

Wedding Music Guide

Wedding Music Guide R [email protected] captivsounds.com 613.304.7884 Wedding Music Guide Classic Love Songs Recessional The Power of Love Celine Dion Signed, Sealed, Delivered Stevie Wonder The Way You Look Tonight Tony Bennett All You Need is Love The Beatles When I Fall in Love Nat King Cole This Will Be Natalie Cole Can You Feel the Love Tonight? Elton John Autumn – Four Seasons Vivaldi Eternal Flame The Bangles Marry You Bruno Mars At Last Etta James I Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley Arrival of the Queen of Handel I Do Westlife Sheba You Are So Beautiful Joe Cocker Home Edward Sharpe Power of Love Luther Vandross 5 Years Time Noah & The Whale I Want to Know What Love Is Foreigner Higher Love Steve Winwood All My Life K-C & Jojo Wouldn’t it be Nice The Beach Boys More Than Words Extreme Somebody Like You Keith Urban One In A Million Bosson Only You Ashanti Is This Love Bob Marley Have I Told You Lately? Rod Stewart Beautiful Day U2 When a Man Loves a Woman Percy Sledge Two of Us Beatles Kiss From a Rose Seal Wedding Party Introduction Wedding Ceremony Songs Party Rock Anthem LMFAO Processional + Bride’s Entrance I Gotta A Feeling Black Eyed Peas Give Me Everything Pitbull Bridal Chorus Wagner Let’s Get It Started Black Eyed Peas Beautiful Day U2 Canon in D Pachabel All of The Lights K anye West Here Comes the Sun The Beatles Sexy And I Know It LMFAO Guitar Concerto in D Major Vivaldi Forever Chris Brown Winter Largo, Four Seasons Vivaldi We Found Love Rihanna Trumpet Voluntary Jeremiah Clark Bring ‘Em Out T.I. -

Lyrics and the Law Legal Studies 391L Spring 2007

Lyrics and the Law Legal Studies 391L Spring 2007 Lyrics and the Law Legal Studies 391L Aaron Lorenz Spring 2007 121 Gordon Hall Tuesday/Thursday 1:00-2:15 545.2647 Bartlett 202 Office Hours: Tues/Thurs 12-1 and Wed 2-3 www.umass.edu/legal/Lorenz [email protected] When modes of music change, It (music) is harmless – except, of the fundamental laws of the State course, that when lawlessness has always change with them. established itself there, it flows over little by little into characters and ways of - Plato (428 BC – 348 BC) life. Then, greatly increased, it steps out into private contracts, and from private Sometimes I can dig instrumental contracts, Socrates, it makes its insolent music. But lyrics important. The whole way into the laws and government, thing complete is the important thing. until in the end it overthrows People who listen to the music and everything, public and private. don’t listen to the words soon start listening to the words. As long as ya - Adeimantus (450 BC – 385 BC) want to listen, ya hear the words even if ya don’t understand everything. Music is your own experience, your own thoughts, your wisdom. If you - Bob Marley (1945 – 1981) don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn. They teach you there’s a boundary line to music. But, man, there’s no boundary line to art. - Charlie Parker (1920 - 1955) Music can be designed to bring about change in society. Pop music may have a message of joy that allows one to forget about their worries; folk music may be professing a change within the political structure; jazz music can speak without words to the past and present inequities; blues tells the tale of what it is like to struggle; and reggae music attempts to expose the inequalities in society by chanting metaphors of politics and religion. -

Downloaded PDF File of the Original First-Edi- Pete Extracted More Music from the Song Form of the Chart That Adds Refreshing Contrast

DECEMBER 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; North Carolina: Robin -

Chanticleer| Vol 42, Issue 22

Jacksonville State University JSU Digital Commons Chanticleer Historical Newspapers 1995-03-09 Chanticleer | Vol 42, Issue 22 Jacksonville State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty Recommended Citation Jacksonville State University, "Chanticleer | Vol 42, Issue 22" (1995). Chanticleer. 1142. https://digitalcommons.jsu.edu/lib_ac_chanty/1142 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Historical Newspapers at JSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chanticleer by an authorized administrator of JSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FEATURES: The two sides of Michael Franti, page 8 SPORTS: Rijle team places sixth in nation, page 14 1 I 1 Fz THE CHANTICLEER 4 v By Jamie Cole sented to the grandjury, only that an indict- Editor in Chief Case timeline ment was filed. "In this case, there's enough Heather under More than two months after an alleged Nov. 9, 1994: Rape is reported at evidence to go to trial," said Nichols. He rape was reported in Fitzpatrick Hall, a Fitzpatrick Hall. said he has "been in this business long criticism from grand jury indicted Daniel Brian Godwin, Jan. 13, 1995: Grand jury files indict- enough not to speculate" about anything 21, of Oxford, in connection with the al- ment charging Daniel Brian Godwin, 21, else. with first degree rape. deaf community leged crime. Wood said the case is still in its "infancy Jan. 30, 1995: Godwin is arrested and According to University Police Depart- released on bond. stages." A rather _laid-back Heather ment records, on Nov. -

Adam Deitch Quartet - Egyptian Secrets

Adam Deitch Quartet - Egyptian Secrets Adam Wakefield - Gods & Ghosts Adrian Quesada - Look at My Soul: The Latin Shade of Texas Soul Ages and Ages - Me You They We Alexa Rose - Medicine for Living Alfred Serge IV - Sleepless Journey Alice Wallace - Into the Blue Allah-Las - Lahs Allison deGroot & Tatiana Hargreaves - Allison deGroot & Tatiana Hargreaves Allison Moorer - Blood Altin Gun - Gece Amanda Anne Platt & The Honeycutters - Live at the Grey Eagle Amy LaVere - Painting Blue Amy McCarley - Meco Anders Osborne - Buddha and the Blues Andrew Bird - My Finest Work Yet Andrew Combs - Ideal Man Andy Bassford - The Harder They Strum Andy Statman - Monroe Bus Andy Thorn - Frontiers Like These Angelique Kidjo - Celia Angie McMahon - Salt Arlen Roth - TeleMasters Armchair Boogie - What Does Time Care? Austin Plaine - Stratford Aubrey Eisenman and The Clydes - Bowerbird Avery R. Young - Tubman Avett Brothers - Closer Than Together Aymee Nuviola - A Journey Through Cuban Music Bad Popes - Still Running Balsam Range - Aeonic Bayonics - Resilience BB King Blues Band - The Soul of the King Beatific - The Sunshine EP Bedouine - Bird Songs of a Killjoy Ben Dickey - A Glimmer On the Outskirts Beth Bombara - Evergreen Beth Wood - The Long Road Better Oblivion Community Center - Phoebe Bridgers & Conor Oberst Big Band of Brothers - A Jazz Celebration of the Allman Brothers Band Big Thief - Two Hands Bill Noonan - Catawba City Blues Billy Strings - Home Black Belt Eagle Scout - At the Party With My Brown Friends Black Joe Lewis & The Honeybears - The Difference Between Me & You Black Keys - Let's Rock Blue Highway - Somewhere Far Away Blue Moon Rising - After All This Time Bobby Rush - Sitting On Top of the Blues Bombadil - Beautiful Country Bon Iver - I, I Bonnie Bishop - The Walk Brittany Howard - Jaime Brother Oliver - Well, Hell Bruce Cockburn - Crowing Ignites Bruce Hornsby - Absolute Zero Buddy & Julie Miller - Breakdown on 20th Ave. -

File Type Pdf Music Program Guide.Pdf

MOOD:MEDIA 2020 MUSIC PROGRAM GUIDE 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hitline* ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Current Top Charting Hits Sample Artists: Bebe Rexha, Shawn Mendes, Maroon 5, Niall Sample Artists: Ariana Grande, Zedd, Bebe Rexha, Panic! Horan, Alice Merton, Portugal. The Man, Andy Grammer, Ellie At The Disco, Charlie Puth, Dua Lipa, Hailee Steinfeld, Lauv, Goulding, Michael Buble, Nick Jonas Shawn Mendes, Taylor Swift Hot FM ‡ Be-Tween Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Family-Friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Ed Sheeran, Alessia Cara, Maroon 5, Vance Sample Artists: 5 Seconds of Summer, Sabrina Carpenter, Joy, Imagine Dragons, Colbie Caillat, Andy Grammer, Shawn Alessia Cara, NOTD, Taylor Swift, The Vamps, Troye Sivan, R5, Mendes, Jess Glynne, Jason Mraz Shawn Mendes, Carly Rae Jepsen Metro ‡ Cashmere ‡ Chic Metropolitan Blend Warm Cosmopolitan Vocals Sample Artists: Little Dragon, Rhye, Disclosure, Jungle, Sample Artists: Emily King, Chaka Khan, Durand Jones & The Maggie Rogers, Roosevelt, Christine and The Queens, Flight Indications, Sam Smith, Maggie Rogers, The Teskey Brothers, Facilities, Maribou State, Poolside Diplomats of Solid Sound, Norah Jones, Jason Mraz, Cat Power Pop Style Youthful Pop Hits Divas Sample Artists: Justin Bieber, Taylor Swift, DNCE, Troye Sivan, Dynamic Female Vocals Ellie Goulding, Ariana Grande, Charlie Puth, Kygo, The Vamps, Sample Artists: Chaka Khan, Amy Winehouse, Aretha Franklin, Sabrina Carpenter Ariana Grande, Betty Wright, Madonna, Mary J. Blige, ZZ Ward, Diana Ross, Lizzo, Janelle Monae -

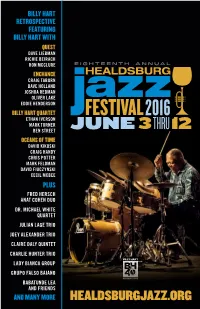

Billy Hart Retrospective Featuring Billy Hart with Plus and Many More

BILLY HART RETROSPECTIVE FEATURING BILLY HART WITH QUEST DAVE LIEBMAN RICHIE BEIRACH RON MCCLURE ENCHANCE CRAIG TABORN DAVE HOLLAND JOSHUA REDMAN OLIVER LAKE EDDIE HENDERSON BILLY HART QUARTET ETHAN IVERSON MARK TURNER BEN STREET OCEANS OF TIME DAVID KIKOSKI CRAIG HANDY CHRIS POTTER MARK FELDMAN DAVID FIUCZYNSKI CECIL MCBEE PLUS FRED HERSCH ANAT COHEN DUO DR. MICHAEL WHITE QUARTET JULIAN LAGE TRIO JOEY ALEXANDER TRIO CLAIRE DALY QUINTET CHARLIE HUNTER TRIO LADY BIANCA GROUP GRUPO FALSO BAIANO BABATUNDE LEA AND FRIENDS AND MANY MORE So many great jazz masters have had tributes to their talent and contributions, I felt one for Billy was way overdue. He is truly one of the greatest drummers in jazz history. He has been on thousands of recordings over his 50-year career and, in turn, has enhanced the careers of several exceptional musicians. He has also been a true friend to Healdsburg Jazz Festival, performing here 11 out of the past 17 years. Many people do not know his deep contributions to jazz and the vast number of musicians he has performed and recorded with over the years as leader, sideman and collaborator: Shirley Horn, Wes Montgomery, Betty Carter, Jimmy Smith, McCoy Tyner, Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Stan Getz, and so many more (see the Billy Hart discography on our website). When he began to lead his own bands in 1977, they proved to be both disciplined and daring. For this tribute, we will take you through his musical history, and showcase his deep passion for jazz and the breadth of his achievements. -

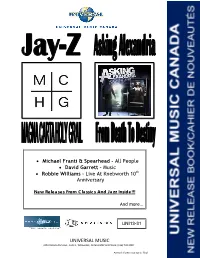

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Michael Franti & Spearhead – All People • David

Michael Franti & Spearhead – All People David Garrett – Music Robbie Williams – Live At Knebworth 10th Anniversary New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI13-31 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: JAY‐Z / MAGNA CARTA HOLY GRAIL (Standard Version) Bar Code: Cat. #: DEFW4027102 Price Code: SP Order Due: ASAP Release Date: July 9, 2013 8 57018 00418 2 File: Rap / Hip Hop Genre Code: 34 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: *SHORT SELL CYCLE “Holy Grail” ft. Justin Timberlake *NOT ACTUAL COVER Artist/Title: JAY‐Z / MAGNA CARTA HOLY GRAIL (Deluxe Version) Bar Code: Cat. #: B001887702 Price Code: SPS Order Due: July 4, 2013 Release Date: July 23, 2013 8 57018 00414 4 File: Rap / Hip Hop Genre Code: 34 Box Lot: 25 Key Tracks: *SHORT SELL CYCLE “Holy Grail” ft. Justin Timberlake *NOT ACTUAL COVER KEY POINTS: • Over 50 Million Albums sold worldwide – 1 million in Canada! • 10 Grammy Awards including 3 for his 2009 release “Blueprint 3” which debuted #1 in Canada • Previous album Watch The Throne with Kanye West has scanned over 130,000 units • Magna Carta Holy Grail includes 15 brand new songs! • Deluxe Version includes intricate 6‐panel soft pack, 28‐page booklet with black o‐card. The idea behind the package is that it needs to be destroyed in order for the information inside to be revealed. • Massive advertising & promotional campaigns running from release throughout the