Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video Arrow Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just How Nasty Were the Video Nasties? Identifying Contributors of the Video Nasty Moral Panic

Stephen Gerard Doheny Just how nasty were the video nasties? Identifying contributors of the video nasty moral panic in the 1980s DIPLOMA THESIS submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister der Philosophie Programme: Teacher Training Programme Subject: English Subject: Geography and Economics Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Evaluator Univ.-Prof. Dr. Jörg Helbig, M.A. Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik Klagenfurt, May 2019 i Affidavit I hereby declare in lieu of an oath that - the submitted academic paper is entirely my own work and that no auxiliary materials have been used other than those indicated, - I have fully disclosed all assistance received from third parties during the process of writing the thesis, including any significant advice from supervisors, - any contents taken from the works of third parties or my own works that have been included either literally or in spirit have been appropriately marked and the respective source of the information has been clearly identified with precise bibliographical references (e.g. in footnotes), - to date, I have not submitted this paper to an examining authority either in Austria or abroad and that - when passing on copies of the academic thesis (e.g. in bound, printed or digital form), I will ensure that each copy is fully consistent with the submitted digital version. I understand that the digital version of the academic thesis submitted will be used for the purpose of conducting a plagiarism assessment. I am aware that a declaration contrary to the facts will have legal consequences. Stephen G. Doheny “m.p.” Köttmannsdorf: 1st May 2019 Dedication I I would like to dedicate this work to my wife and children, for their support and understanding over the last six years. -

Resavoring Cannibal Holocaust As a Mockumentary

hobbs Back to Issue 7 "Eat it alive and swallow it whole!": Resavoring Cannibal Holocaust as a Mockumentary by Carolina Gabriela Jauregui ©2004 "The worst returns to laughter" Shakespeare, King Lear We all have an appetite for seeing, an appétit de l'oeuil as Lacan explains it: it is through our eyes that we ingest the Other, the world.1 And in this sense, what better way to introduce a film on anthropophagy, Ruggero Deodato's 1979 film, Cannibal Holocaust, than through the different ways it has been seen.2 It seems mankind has forever been obsessed with the need to understand the world through the eyes, with the need for visual evidence. From Thomas the Apostle, to Othello's "ocular proof," to our television "reality shows," as the saying goes: "Seeing is believing." We have redefined ourselves as Homo Videns: breathers, consumers, dependants, and creators of images. Truth, in our society, now hinges on the visual; it is mediated by images. Thus it is from the necessity for ocular proof that Cinéma Vérité, Direct Cinema, documentary filmmaking and the mockumentary or mock-documentary genre stem. It is within this tradition that the Italian production Cannibal Holocaust inserts itself, as a hybrid trans-genre film. To better understand this film, I will not only look at it as a traditional horror film, but also as a contemporary mockumentary satire that presents itself as "reality" and highlights the spectator’s eye/I’s primal appetite. In the manner of Peter Watkins' film Culloden, Deodato's film is intended to confuse the audience's -

International Sales Autumn 2017 Tv Shows

INTERNATIONAL SALES AUTUMN 2017 TV SHOWS DOCS FEATURE FILMS THINK GLOBAL, LIVE ITALIAN KIDS&TEEN David Bogi Head of International Distribution Alessandra Sottile Margherita Zocaro Cristina Cavaliere Lucetta Lanfranchi Federica Pazzano FORMATS Marketing and Business Development [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mob. +39 3351332189 Mob. +39 3357557907 Mob. +39 3334481036 Mob. +39 3386910519 Mob. +39 3356049456 INDEX INDEX ... And It’s Snowing Outside! 108 As My Father 178 Of Marina Abramovic 157 100 Metres From Paradise 114 As White As Milk, As Red As Blood 94 Border 86 Adriano Olivetti And The Letter 22 46 Assault (The) 66 Borsellino, The 57 Days 68 A Case of Conscience 25 At War for Love 75 Boss In The Kitchen (A) 112 A Good Season 23 Away From Me 111 Boundary (The) 50 Alex&Co 195 Back Home 12 Boyfriend For My Wife (A) 107 Alive Or Preferably Dead 129 Balancing Act (The) 95 Bright Flight 101 All The Girls Want Him 86 Balia 126 Broken Years: The Chief Inspector (The) 47 All The Music Of The Heart 31 Bandit’s Master (The) 53 Broken Years: The Engineer (The) 48 Allonsanfan 134 Bar Sport 118 Broken Years: The Magistrate (The) 48 American Girl 42 Bastards Of Pizzofalcone (The) 15 Bruno And Gina 168 Andrea Camilleri: The Wild Maestro 157 Bawdy Houses 175 Bulletproof Heart (A) 1, 2 18 Angel of Sarajevo (The) 44 Beachcombers 30 Bullying Lesson 176 Anija 173 Beauty And The Beast (The) 54 Call For A Clue 187 Anna 82 Big Racket (The) -

La Dolce Vita Actress Anita Ekberg Dies at 83

La Dolce Vita actress Anita Ekberg dies at 83 Posted by TBN_Staff On 01/12/2015 (29 September 1931 – 11 January 2015) Kerstin Anita Marianne Ekberg was a Swedish actress, model, and sex symbol, active primarily in Italy. She is best known for her role as Sylvia in the Federico Fellini film La Dolce Vita (1960), which features a scene of her cavorting in Rome's Trevi Fountain alongside Marcello Mastroianni. Both of Ekberg's marriages were to actors. She was wed to Anthony Steel from 1956 until their divorce in 1959 and to Rik Van Nutter from 1963 until their divorce in 1975. In one interview, she said she wished she had a child, but stated the opposite on another occasion. Ekberg was often outspoken in interviews, e.g., naming famous people she couldn’t bear. She was also frequently quoted as saying that it was Fellini who owed his success to her, not the other way around: "They would like to keep up the story that Fellini made me famous, Fellini discovered me", she said in a 1999 interview with The New York Times. Ekberg did not live in Sweden after the early 1950s and rarely visited the country. However, she welcomed Swedish journalists into her house outside Rome and in 2005 appeared on the popular radio program Sommar, and talked about her life. She stated in an interview that she would not move back to Sweden before her death since she would be buried there. On 19 July 2009, she was admitted to the San Giovanni Hospital in Rome after falling ill in her home in Genzano according to a medical official in the hospital's neurosurgery department. -

LCCC Thematic List

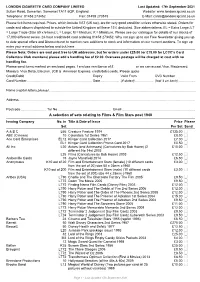

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 17th September 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name -

From 5 to 13 October at Fiere Di Parma

Press Release MERCANTEINFIERA AUTUMN THE POETRY OF THE HEEL, ITALIAN MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY AND FOUR CENTURIES OF ART HISTORY From 5 to 13 October at Fiere di Parma Mercanteinfiera, the Fiere di Parma international exhibition of antiques, modern antiques, design and vintage collectibles, is an increasingly “fusion” event. Protagonists of the 38th edition are the Villa Foscarini Rossi Shoes Museum of the LVMH Group and the BDC Art Gallery in Parma, owned by Lucia Bonanni ad Mauro del Rio, curators of the two collateral exhibitions. On the one hand, stylists such as Dior, Kenzo, Yves Saint Laurent and Nicholas Kirkwood highlighted by the far-sightedness of the entrepreneur Luigino Rossi, the Muse- um’s founder. On the other, masters of the visual language such as Ghirri, Sottsass, Jodice, as well as the paparazzi. With Lino Nanni and Elio Sorci, we will dive into the years of the exuberant Dolce Vita. (Parma, 30 September 2019) - At the beginning there were” pianelle”, or “chopines”, worn by both aristocratic women and commoners to protect their feet from mud and dirt. They could be as high as 50 cm (but only for the richest ladies), while four centuries later Mari- lyn Monroe would build her image on a relatively very modest 11-cm peep toe heel. For Yves Saint Laurent the perfect stride required a 9-cm heel. This was too high for the Swinging Sixties of London and Twiggy, when ballerinas were the footwear of choice. Whether high, low, with a 9 or 11cm heel, shoes have always been the best-loved accesso- ry of fashion victims and many others and they are the protagonists of the collateral exhi- bition “In her Shoes. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress

Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985 By Xavier Mendik Bodies of Desire and Bodies in Distress: The Golden Age of Italian Cult Cinema 1970-1985, By Xavier Mendik This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Xavier Mendik All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5954-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5954-7 This book is dedicated with much love to Caroline and Zena CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................... ix Foreword ................................................................................................... xii Enzo G. Castellari Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Bodies of Desire and Bodies of Distress beyond the ‘Argento Effect’ Chapter One .............................................................................................. 21 “There is Something Wrong with that Scene”: The Return of the Repressed in 1970s Giallo Cinema Chapter Two ............................................................................................ -

Le Commedie Sexy All’Italiana Girate In

| 1 LE COMMEDIE SEXY ALL’ITALIANA GIRATE IN ABRUZZO CHE SALVARONO IL CINEMA IN CRISI di Piercesare Stagni* L’AQUILA – La “commedia sexy” nasce intorno alla metà degli anni Settanta come www.virtuquotidiane.it | 2 sottogenere del filone principale della commedia all’italiana: in quel periodo il cinema viveva nel nostro paese una profonda crisi di spettatori e si corse quindi ai ripari cercando nuove idee. Questo nuovo genere fondeva l’erotismo con la comicità ed era ispirato ai personaggi lanciati in quegli anni da Lando Buzzanca e Carlo Giuffrè, efficacissimi rappresentanti di quel “maschio italico” che spesso consolava le vedove inconsolabili. La novità era la presenza contemporanea nelle storie di diverse categorie di interpreti: l’attore brillante principale, il comico di spalla a cui affidare battute più o meno grevi e ovviamente l’immancabile bomba erotica. Era nata la commedia sexy, con registi come Sergio Martino, Michele Massimo Tarantino, Nando Cicero, Mariano Laurenti e tutta la loro schiera di improbabili ed audaci “dottoresse”, “insegnanti”, “liceali”, “professoresse”, “cameriere”, “soldatesse”, “infermiere” e “poliziotte”. Tra gli attori come non citare Lino Banfi, Renzo Montagnani, Aldo Maccione, Mario Carotenuto, tra i comici ovviamente Alvaro Vitali e Gianfranco D’Angelo, con le dive sexy la memoria va subito ad Edwige Fenech, Annamaria Rizzoli, Nadia Cassino, Barbara Bouchet, Pamela Miti, Lilli Carati, Carmen Russo, Carmen Villani. Nel 1981 ben tre di queste pellicole, che, non dimentichiamolo mai, salvarono per anni il cinema italiano dal disastro con i loro incassi stellari, furono girate quasi completamente in Abruzzo: La maestra di sci, C’è un fantasma nel mio letto e Bollenti spiriti. -

Babel Film Festival 2019 Anna Karina, Il Volto

_ n.3 Anno IX N. 79 | Gennaio 2020 | ISSN 2431 - 6739 Politiche educative e formazione culturale Anna Karina, il volto iconico passato e futuro cinematografica per i giovani in Germania della Nouvelle Vague Danimarca 1940 – Parigi 14 Dicembre 2019 Il cinema educa alla in programma dall'8 di questo mese al 1° mar- vita! zo prossimo. Se n'è andata il 14 dicembre, die- Dopo una visita a fine Novembre a Francoforte ci giorni dopo l'inaugurazione dell'atelier (ben sul Meno di una delegazione di Diari di Cine- successivo alle loro comuni imprese in cop- club, la responsabile delle attività di alfabetiz- pia) di Godard, "Le Studio d'Orphée" alla Fon- zazione del dipartimento di educazione cine- dazione Prada. Aveva appena fatto in tempo matografica del DDF - DeutschesFilminstitut & Bergamo a volerla come ospite d'onore e sog- Filmmuseum, Christine Kopf interviene per getto presente e parlante della propria retro- raccontare la storia e le politiche culturali dell’i- spettiva nella scorsa edizione, come Cannes a stituto di cinema tedesco dedicarle il manifesto e Bologna a... cineritro- varla l'anno precedente. A oltre sessant'anni Nei 124 anni della sua esi- dalla sua esplosione, la nouvelle vague si sta pro- stenza, il cinema ha subi- gressivamente quanto inesorabilmente conge- to cambiamenti incredi- dando. Nella tragedia, col suicidio di Jean Se- bili. Già dalle sfarfallanti berg (1979); nel dramma, con le scomparse brevi sequenze delle pri- premature di Truffaut (‘84) e Demy ('90); per me immagini, quelle che naturale uscita dalla vita, come nei casi di sono state lanciate da Chabrol e Rohmer (2010), più di recente di Ri- proiettori rumorosi sugli Non è riuscita a vedere e a farsi vedere, come vette (2016), Jeanne Moreau (2017) e Agnés schermi di sale fieristi- si attendeva e ci si augurava, alla retrospettiva Varda pochi mesi or sono. -

Westerns…All'italiana

Issue #70 Featuring: TURN I’ll KILL YOU, THE FAR SIDE OF JERICHO, Spaghetti Western Poster Art, Spaghetti Western Film Locations in the U.S.A., Tim Lucas interview, DVD reviews WAI! #70 The Swingin’ Doors Welcome to another on-line edition of Westerns…All’Italiana! kicking off 2008. Several things are happening for the fanzine. We have found a host or I should say two hosts for the zine. Jamie Edwards and his Drive-In Connection are hosting the zine for most of our U.S. readers (www.thedriveinconnection.com) and Sebastian Haselbeck is hosting it at his Spaghetti Westerns Database for the European readers (www.spaghetti- western.net). Our own Kim August is working on a new website (here’s her current blog site http://gunsmudblood.blogspot.com/ ) that will archive all editions of the zine starting with issue #1. This of course will take quite a while to complete with Kim still in college. Thankfully she’s very young as she’ll be working on this project until her retirement 60 years from now. Anyway you can visit these sites and read or download your copy of the fanzine whenever you feel the urge. Several new DVD and CD releases have been issued since the last edition of WAI! and co-editor Lee Broughton has covered the DVDs as always. The CDs will be featured on the last page of each issue so you will be made aware of what is available. We have completed several interviews of interest in recent months. One with author Tim Lucas, who has just recently released his huge volume on Mario Bava, appears in this issue. -

The Thousand and One Days of Aristide (2018) by Stephen Thrower

ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 CONTENTS ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 5 Cast and Crew 7 The Thousand and One Days of Aristide (2018) by Stephen Thrower 21 The Angel Ends Where the Devil Begins: Shooting Death Smiles on a Murderer (2018) ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO by Roberto Curti 31 An Interview with Romano Scandariato (1995) 42 About the Transfer ARROW VIDEO2 ARROW VIDEO 3 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CAST Ewa Aulin Greta von Holstein Klaus Kinski Dr. Sturges Angela Bo Eva von Ravensbrück Sergio Doria Walter von Ravensbrück Giacomo Rossi Stuart Dr. von Ravensbrück Luciano Rossi Franz, Greta’s brother Attilio Dottesio Inspector Dannick Marco Mariani Simeon, the butler ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CREW Directed by Aristide Massaccesi Story by Aristide Massaccesi Screenplay by A. Massaccesi, R. Scandariato and C. Bernabei Assistant Director Romano Scandariato Director of Photography Aristide Massaccesi Cameraman Guglielmo Vincioni Assistant Cameraman Gianlorenzo Battaglia ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Editors Piera Bruni and Gianfranco Simoncelli Musical Score by Berto Pisano Production Manager Oscar Santaniello (as Oskar Santaniello) Production Assistants Massimo Alberini and Sergio Rosa Sets and Costumes Claudio Bernabei Make-up Maria Grazia Nardi ARROW VIDEO4 ARROW VIDEO 5 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO THE THOUSAND AND ONE DAYS OF ARISTIDE by Stephen Thrower Aristide Massaccesi, better known by his most frequent pseudonym ‘Joe D’Amato’, was an astoundingly prolific filmmaker who shot nearly two hundred films across 26 years. He began directing in the early 1970s, just as censorship was being relaxed in the major film markets.