A Little of My Quest, by Alice Coghlan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing Creative Partnerships Lower Ground Floor 17 Kildare Street Dublin 2 D02 CY90 T +353 1 662 9238 W Businesstoarts.Ie E [email protected]

Business to Arts | Developing Creative Partnerships Lower Ground Floor 17 Kildare Street Dublin 2 D02 CY90 T +353 1 662 9238 W businesstoarts.ie E [email protected] Arts Affiliates Flying Turtle Productions Michelle Cahill AboutFACE Ireland Gaiety School of Acting MoLI - Museum of Literature Access Cinema Galway Community Circus Ireland Aimée van Wylick Galway Dance Project Music Generation Alan James Burns Galway International Arts Festival Music Network ALSA Productions Galway Theatre Festival Na Piobairi Uilleann Arts & Disability Ireland Galway Traditional Orchestra Naoise Nunn Axis Arts Centre Glasnevin Trust National Concert Hall Baboró International Arts Festival for Glass Mask Theatre National Gallery of Ireland Children Graphic Studio Dublin National Irish Visual Arts Library Ballet Ireland Helle Helsner National Library of Ireland Bitter Like A Lemon Helium National Museum of Ireland BKB Visual Arts Studio Hues Productions National Print Museum Black Church Print Studio Hunt Museum Niamh Shaw Blue Teapot Theatre Company IMMA Oireachtas na Gaeilge Brian Palfrey IMRAM Olga Magliocco Butler Gallery Irish Architecture Foundation Parallel Editions Cavan County Council Arts Office Irish Association of Youth Orchestras Pavilion Theatre Chamber Choir Ireland Irish Chamber Orchestra Poetry Ireland Chester Beatty Library Irish Film Institute Project Arts Centre Children's Books Ireland Irish Georgian Society Publishing Ireland Civic Theatre Irish Landmark Trust Rebecca Lyons Common Ground Irish Modern Dance Theatre Riverbank Arts -

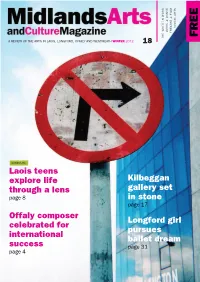

Issue 18 Midlands Arts 4:Layout 1

VISUAL ARTS MUSIC & DANCE ISSUE & FILM THEATRE FREE THE WRITTEN WORD A REVIEW OF THE ARTS IN LAOIS, LONGFORD, OFFALY AND WESTMEATH WINTER 2012 18 COVER PIC Laois teens explore life Kilbeggan through a lens gallery set page 8 in stone page 17 Offaly composer Longford girl celebrated for pursues international ballet dream success page 31 page 4 Toy Soldiers, wins at Galway Film Fleadh Midland Arts and Culture Magazine | WINTER 2010 Over two decades of Arts and Culture Celebrated with Presidential Visit ....................................................................Page 3 A Word Laois native to trend the boards of the Gaiety Theatre Midlands Offaly composer celebrated for international success .....Page 4 from the American publisher snaps up Longford writer’s novel andCulture Leaves Literary Festival 2012 celebrates the literary arts in Laois on November 9, 10............................Page 5 Editor Arts Magazine Backstage project sees new Artist in Residence There has been so Irish Iranian collaboration results in documentary much going on around production .....................................................................Page 6 the counties of Laois, Something for every child Mullingar Arts Centre! Westmeath, Offaly Fear Sean Chruacháin................................................Page 7 and Longford that County Longford writers honored again we have had to Laois teens explore life through the lens...............Page 8 up the pages from 32 to 36 just to fit Introducing Pete Kennedy everything in. Making ‘Friends’ The Doctor -

October 2010 Newsletter:January 2008 Newsletter.Qxd 22/09/2010 14:08 Page 1

October 2010 Newsletter:January 2008 Newsletter.qxd 22/09/2010 14:08 Page 1 OCTOBER 2010 dance ireland NEWS October 2010 Newsletter:January 2008 Newsletter.qxd 22/09/2010 14:08 Page 2 Dance Ireland is the trading name of the Association of Professional Dancers in Ireland Ltd. Established in 1989, Dance Ireland is a membership-led organisation, operating on an all-Ireland basis, dedicated to the promotion of professional dance practice in Ireland. Incorporated in 1992 as a not-for-profit company with limited guarantee, the organisation has evolved into a national, umbrella resource whose core aims are the promotion of dance as a vibrant art form, the provision of support and practical resources for professional dance artists through our training and development programmes and advocacy on dance and choreography issues. Dance Ireland manages DanceHouse, a purpose-built, state-of-the-art dance rehearsal venue, located in the heart of Dublin’s north-east inner city. DanceHouse is at the heart of Dance Ireland activities, as well as being a home for professional dance artists and the wider dance community. Studios are available for hire. In addition to hosting our artistic programme of professional training and development, performances, exhibitions, special events and a fully equipped artists’ resource room, DanceHouse offers a range of evening classes to cater to the interests and needs of the general public. BOARD MEMBERS Adrienne Brown Chairperson, Cindy Cummings, Richard Johnson, Megan Kennedy Secretary, Lisa McLoughlin, Anne Maher, Fearghus Ó Conchúir. DANCE IRELAND PERSONNEL Paul Johnson, Chief Executive Siân Cunningham, General Manager Elisabeth Bisaro, Programme Manager Inga Byrne, Administrator Brenda Crea & Glenn Montgomery, Receptionists/Administrative Assistants Dance Ireland, DanceHouse, Foley Street, Dublin 1. -

HERALDS of the GYMNASTIC CLUBS “YUNAK” up to the BEGINNING of the 20TH CENTURY (Research Note)

178Activities in Physical Education and Sport 2014, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 178-183 HERALDS OF THE GYMNASTIC CLUBS “YUNAK” UP TO THE BEGINNING OF THE 20TH CENTURY (Research note) Sergei Radoev South-West University “Neofit Rilski” Blagoevgrad Faculty “Public Health and Sport” Department “Sport and Kinezitherapy”, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria Abstract In the present work are revealed the prerequisites and the reasons for the appearance of the gymnastic movement in Bulgaria. The accent is put on the fact that the gymnastic exercises are closely connected with the physical preparation of the revolutionaries in the Balkans and have great significance for the resistance and readiness to fight in the crude conditions of revolutionary life. Underlined is the significance of Vassil Levski for the organization of the “gymnastic groups”. Presented are the historic data about the first gymnastic club “Yunak” in Sofia (1895). By one of the Swiss teachers who came to Bulgaria to teach gymnastics, Bulgaria becomes co-founder of the Olympic Games. Described are the reasons for the unification of the different clubs into Union of the Bulgarian gymnastic clubs “Yunak” in Sofia in 1898. Described are the 1st and the 2nd congresses (1898 – 1900) – Sofia, as well as the 1st national meeting – 1900 in Varna, upbringing its members in love to the Homeland. Keywords: physical education, physical development of students, classes in gymnastics, physical exercises, International Gymnastics Federation, Olympic games INTRODUCTION has been preliminary training on horses – getting on and About the history of the physical education and off static or moving horse which is earlier announced by the gymnastics mainly write: Tsonkov (Цонков) (1968); Flavii Vegetsii. -

TANZIMAT in the PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) and LOCAL COUNCILS in the OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840S to 1860S)

TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde einer Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel von ANNA VAKALIS aus Thessaloniki, Griechenland Basel, 2019 Buchbinderei Bommer GmbH, Basel Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel, auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Maurus Reinkowski und Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yonca Köksal (Koç University, Istanbul). Basel, den 05/05/2017 Der Dekan Prof. Dr. Thomas Grob 2 ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………..…….…….….7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………...………..………8-9 NOTES ON PLACES……………………………………………………….……..….10 INTRODUCTION -Rethinking the Tanzimat........................................................................................................11-19 -Ottoman Province(s) in the Balkans………………………………..…….………...19-25 -Agency in Ottoman Society................…..............................................................................25-35 CHAPTER 1: THE STATE SETTING THE STAGE: Local Councils -

All We Say Is 'Life Is Crazy': – Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title All we say is 'Life is crazy': - Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage Author(s) Lonergan, Patrick Publication Date 2009 Lonergan, P. (2009) ' All we say is 'Life is Crazy': - Central and Publication Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage' In: Maria Kurdi, Literary Information and Cultural Relations Between Ireland and Hungary and Central and Eastern Europe' (Eds.) Dublin: Carysfort Press. Publisher Dublin: Carysfort Press Link to publisher's http://www.carysfortpress.com/ version Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/5361 Downloaded 2021-09-28T21:11:04Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. All We Say is ‘Life is Crazy’: – Central and Eastern Europe and the Irish Stage Patrick Lonergan If you had visited the Abbey Theatre during 2007, you might have seen a card displayed prominently in its foyer. ‘Join Us,’ it says, its purpose being to convince visitors to become Members of the Abbey – to donate money to the theatre and, in return, to get free tickets for productions, to have their names listed in show programmes, and to gain access to special events. The choice of image to attract potential donors is easy to understand (Figure 1). The woman, we see, has reached into a chandelier to retrieve a letter, and we can tell from her expression that the discovery she’s made has both surprised and delighted her. Why is she so happy? What does the letter say? And who is that strange man, barely visible, holding her up at such an unusual angle? As well as being eye-catching, the image is also an interesting analogue for the experience of watching great drama. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

A Christian Printer on Trial in the Tanzimat Council of Selanik, Early 1850S: Kiriakos Darzilovitis and His Seditious Books

Cihannüma Tarih ve Coğrafya Araştırmaları Dergisi Sayı I/2 – Aralık 2015, 23-38 A CHRISTIAN PRINTER ON TRIAL IN THE TANZIMAT COUNCIL OF SELANIK, EARLY 1850S: KIRIAKOS DARZILOVITIS AND HIS SEDITIOUS BOOKS Anna Vakali* Abstract The present article deals with Kiriakos Darzilovitis, a Greek-educated Slavophone and the second Christian printer of Selanik. This article touches on some of the main points in Kiriakos’s biography, with two main stations: first, his trial by the city’s Tanzimat council because of the seditious books he was accused of printing; and second, the closure of his bookstore some years later, orchestrated by two Orthodox metropolitans and the local Ottoman authorities. The article follows how an ordinary Ottoman subject was consciously able to manoeuvre his way through different lingual, ethnic identities, citizenships, and even legal jurisdictions. More importantly, Kiriakos’s life story sets an example for the limits of such “navigation.” Indeed, the different governing authorities in the late Ottoman world could punish an individual for not fulfilling the expected commitments of each identity he or she asserted. Keywords: printing, Ottoman Balkans, Selanik, sedition 1850’lerin Başında Selanik Tanzimat Meclisinde Bir Hiristiyan Matbaacının Yargılanması: Kiriakos Darzilovitis ve Fesat Kitapları Özet Bu makale Selanik'in ikinci Hristiyan matbaacısı, Yunan eğitimi almış bir Slavofon olan Kiriakos Darzilovitis hakkındadır ve Kiriakos’un hayatındaki bazı önemli dönüm noktalarına temas etmektedir. Bu dönüm noktalarından ilki, şehrin Tanzimat meclisinde zararlı (fesat) kitaplar basmış olması nedeniyle yargılanması; bir diğeri ise, sahip olduğu kitapçı dükkânının bir kaç yıl sonra iki Ortodoks Metropolit ve yerel Osmanlı otoriteleri eliyle kapatılmasıdır. Bu makale bir Osmanlı tebaasının farklı dilsel, etnik kimlikler ve vatandaşlıklar ve de farklı yargı yetki alanları arasında kendine bilinçli bir biçimde nasıl manevra alanları yarattığının izlerini sürmeyi hedeflemektedir. -

History of Modern Bulgarian Literature

The History ol , v:i IL Illlllf iM %.m:.:A Iiiil,;l|iBif| M283h UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES COLLEGE LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/historyofmodernbOOmann Modern Bulgarian Literature The History of Modern Bulgarian Literature by CLARENCE A. MANNING and ROMAN SMAL-STOCKI BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1960 by Bookman Associates Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 60-8549 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. Foreword This outline of modern Bulgarian literature is the result of an exchange of memories of Bulgaria between the authors some years ago in New York. We both have visited Bulgaria many times, we have had many personal friends among its scholars and statesmen, and we feel a deep sympathy for the tragic plight of this long-suffering Slavic nation with its industrious and hard-working people. We both feel also that it is an injustice to Bulgaria and a loss to American Slavic scholarship that, in spite of the importance of Bulgaria for the Slavic world, so little attention is paid to the country's cultural contributions. This is the more deplorable for American influence in Bulgaria was great, even before World War I. Many Bulgarians were educated in Robert Col- lege in Constantinople and after World War I in the American College in Sofia, one of the institutions supported by the Near East Foundation. Many Bulgarian professors have visited the United States in happier times. So it seems unfair that Ameri- cans and American universities have ignored so completely the development of the Bulgarian genius and culture during the past century. -

Annual Conference Attendance List Key: F = Full Member, I = Individual Member; a = Affiliate Member; NM = Non Member

Annual Conference Attendance list Key: F = Full member, I = Individual member; A = Affiliate member; NM = Non Member # Name Surname Title Organisation Mem 1 Aideen Howard Literary Director Abbey Theatre F 2 Declan Cantwell Director of Finance & Administration Abbey Theatre F 3 Fiach Mac Conghail Director Abbey Theatre F 4 Catherine Carey Director of Public Affairs Abbey Theatre F 5 Barry McKinney General Manager An Tain F 6 Laura Condon Administrator Andrew's Lane Theatre F 7 Mary McVey Andrew's Lane Theatre F 8 Graham Main Festival Manager Anna Livia Dublin Opera Festival F 9 Margaux Nissen Gray Liaison Manager Anna Livia Dublin Opera Festival F 10 Pádraig Naughton Director Arts & Disability Ireland F 11 John McArdle Artistic Director Artswell F 12 Colm Croffy Operations Director Association of Irish Festival Events F 13 Mark O'Brien Local Arts Development Officer axis arts centre Ballymun F 14 Lali Morris Programme Director Baboró Arts Festival for Children F 15 Mona Considine General Manager Backstage Theatre F 16 Anne Maher Managing Director Ballet Ireland F 17 Jenny Walsh Bassett Artistic Director Banner Theatre Company NM 18 Tríona NíDhuibhir General Manager Barabbas F 19 Vincent Dempsey General Manager Barnstorm Theatre Company F 20 Philip Hardy Artistic Director Barnstorm Theatre Company F 21 Frances O'Connor Company Administrator Barnstorm Theatre Company F 22 Peter McNamara Chief Executive Belltable Arts Centre F 23 Karl Wallace Artistic Director Belltable Arts Centre F 24 Alistair Armit Sales Engineer Blackbaud Europe NM 25 -

Subprogramme „Comenius“ Multilateral, Bilateral and Regional School Partnerships

Subprogramme „Comenius“ Multilateral, bilateral and regional school partnerships Started projects 2010 Multilateral school partnerships Cultural cocktail Target group: Pupils, teachers, parents. Project Summary: The “Cultural Cocktail” project will promote the deepening of knowledge about the language and spe- cifics will facilitate the understanding of these characteristics, and its main purpose is to create a cultural cocktail, made with love, friendship, peace, so that many people can try it. If this target is achieved, the project can become a good tool to achieve the ideal of brotherhood and understanding among people and peace on earth. Furthermore, we want children to spend their free time in practical activities to develop their interests and skills. We would like to create clubs – such as folk dances, children’s games 1 and humorous characters. Contact information: Subprogramme „Comenius“Subprogramme Started projects 2010 Coordinator: Skola „Ozolnieku viduskola“ OU “P. Volov” Shumen Municipality, Latvia , Ozolnieku LV-3018 Madara village 9971, “Khan Krum” 15, tel.: +359 54 950 091 tel.: +371 630 506 58 e-mail : [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Partners: Zeshpol Szkoła spetsialnih Kojaali Anadolu Kalkanma pshi rezydentem pomochi spolechney Vakaf Ilkyoretim okulu Poland, Zavadzkie 04274 Turkey, Skaria 54000, tel.: +90 264812 1944 tel.: +48 77 462 0049 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Agrupamento Vertical de eskolas Grupul Scolari de transporturi auto de Oliveira do Douro Romania, Kraiova 2800001, Portugal, Vila Nova de Gaia 4430-001 tel.: +40 251 427 636 tel.: +351 22 379 48 07 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail : [email protected] Obershule an der Lerchenstrase EB 1/JI ESCO dezembro Aldella Nova, Germany , Bremmen 28078-28199 Portugal, Vila Nova de Gaia 4430-001 tel.: +49 361 792 63 e-mail : [email protected] e-mail : [email protected] Project number: LLP-2010-COM-MP-132 Multilateral school partnerships European Children Celebrate Target group: 3-5 year old children. -

Dramaturg, Script Editor and Facilitator

Dan Colley Creative Director/Producer BA (hons): English and Philosophy, NUI Galway [email protected] FETAC 5: Youth Theatre Facilitation, Youth Theatre Ireland I am a creative director and producer specialising in ensemble-devised theatre, theatre for young audiences, comedy, community participation, puppetry, and outdoor spectacle. I am an experienced dramaturg, script editor and facilitator. I trained as a Youth Theatre Facilitator with Youth Theatre Ireland and hold a BA (hons) in English and Philosophy from NUI Galway. I am a Member of the Project Arts Centre and I am Theatre Artist in Residence with the Riverbank Arts Centre, Newbridge. Director Danse Macabre Creative Director Macnas Galway, Oct 2019 A Very Old Man With Enormous Director/Co-Writer for Stage Wings By Gabriel Garcia Marquez Riverbank Arts Centre, July 2019 Collapsing Horse Dublin Fringe Festival, September 2019 Requiem for the Truth Co-Director Text ed. by Robert Grant and Dan Colley 2017: Dublin Fringe Festival Music by James O’Leary 2018 Tour: Bergen Norway Fringe, Waterford Imagine Arts Collapsing Horse & Stomptown Brass Festival, Cork Jazz Festival, Pepper Canister in Dublin. The Water Orchard Co-Director By Eoghan Quinn Collapsing Horse & Project Arts Centre Project Arts Centre Upstairs, July 2017 The Aeneid Director & Co-Writer By Dan Colley and cast Collapsing Horse Dublin Fringe Festival, Sept 2016 Conor: at the end of the Universe Director & Writer By Dan Colley Draíocht Arts Centre, Riverbank Art Centre, Linenhall Arts Collapsing Horse Centre, The Ark. November