Consultation on the Resale of Tickets for Entertainment and Sporting Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Af20-Booking-Guide.Pdf

1 SPECIAL EVENT YOU'RE 60th Birthday Concert 6 Fire Gardens 12 WRITERS’ WEEK 77 Adelaide Writers’ Week WELCOME AF OPERA Requiem 8 DANCE Breaking the Waves 24 10 Lyon Opera Ballet 26 Enter Achilles We believe everyone should be able to enjoy the Adelaide Festival. 44 Between Tiny Cities Check out the following discounts and ways to save... PHYSICAL THEATRE 45 Two Crews 54 Black Velvet High Performance Packing Tape 40 CLASSICAL MUSIC THEATRE 16 150 Psalms The Doctor 14 OPEN HOUSE CONCESSION UNDER 30 28 The Sound of History: Beethoven, Cold Blood 22 Napoleon and Revolution A range of initiatives including Pensioner Under 30? Access super Mouthpiece 30 48 Chamber Landscapes: Pay What You Can and 1000 Unemployed discounted tickets to most Cock Cock... Who’s There? 38 Citizen & Composer tickets for those in need MEAA member Festival shows The Iliad – Out Loud 42 See page 85 for more information Aleppo. A Portrait of Absence 46 52 Garrick Ohlsson Dance Nation 60 53 Mahler / Adès STUDENTS FRIENDS GROUPS CONTEMPORARY MUSIC INTERACTIVE Your full time student ID Become a Friend to access Book a group of 6+ 32 Buŋgul Eight 36 unlocks special prices for priority seating and save online and save 15% 61 WOMADelaide most Festival shows 15% on AF tickets 65 The Parov Stelar Band 66 Mad Max meets VISUAL ART The Shaolin Afronauts 150 Psalms Exhibition 21 67 Vince Jones & The Heavy Hitters MYSTERY PACKAGES NEW A Doll's House 62 68 Lisa Gerrard & Paul Grabowsky Monster Theatres - 74 IN 69 Joep Beving If you find it hard to decide what to see during the Festival, 2020 Adelaide Biennial . -

Secondary Ticketing

BRIEFING PAPER Number 4715, 11 September 2020 By Lorraine Conway Secondary ticketing Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Consumer protection 3. Reviews: secondary ticketing 4. Enforcement action 5. FIFA files a criminal complaint against Viagogo 6. Parliamentary question and debate 7. Appendix: chronology of past initiatives www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Secondary ticketing Contents Summary 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Consumer protection 5 3. Reviews: secondary ticketing 8 3.1 Professor Waterson’s review 8 3.2 Government response to the Waterson report 9 3.3 CMA review 10 3.4 The Culture, Media and Sport (CMS) Committee 11 3.5 Investigation by Which? 13 4. Enforcement action 14 4.1 Action taken by ASA 14 4.2 Action taken by CMA 15 Independent review of Viagogo’s compliance 17 CMA action against StubHub 18 5. FIFA files a criminal complaint against Viagogo 19 6. Parliamentary question and debate 20 7. Appendix: chronology of past initiatives 21 Cover page image copyright Holidays: Day 15 by Lachlan Hardy. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 11 September 2020 Summary The online resale of tickets (the secondary ticketing market) applies to recreational, sporting or cultural events in the UK. Secondary ticketing, especially pricing, is a subject that attracts much public interest. Recently, there have been various investigations of this sector resulting in some enforcement activity. Following the introduction of the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (CRA 2015), the Government commissioned an independent report by Professor Michael Waterson to explore the effectiveness of consumer protection measures concerning online secondary ticketing facilities. -

Reeperbahn Festival Conference MAG / SEPT 2017

CONFERENCE 20 – 23 SEPT 2017 MAG Branded PartnershipsBranded Algorithms and on Hackney Camille Licensing and Sync Time for Diversity for Time Equality and Vanessa Reed on Keychange – Photo: Bonaparte © Musik Bewegt / Henning Heide Henning / Bewegt Musik © Bonaparte Photo: Raise Your Voice Voice Raise Your year´s This Conference Focus Music on and Politics mobile apps for your festival proudly presents the official app Available on the App Store and Google Play Meet us in Hamburg in September! Contact Scandinavia - Esben Christensen Contact GAS - Sarah Schwaab [email protected] [email protected] _ INDEX EDITORIAL 4 mobile apps for your festival RAISE YOUR VOICE The International Music World Is Turning Up 7 Its Political Volume SHIRLEY MANSON Early Days In Madison 15 DAVE ALLEN proudly presents Streaming and Music Culture 21 LIVE FOR (RE)SALE A Sort of Darknet for Tickets 25 VANESSA REED Closing the Gender Gap 31 TERRY MCBRIDE Understanding the Value of Music and 36 How to Effectively Monetize It UNSIGNED VS SIGNED Do Artists Benefit from Blockchain? 39 CAMILLE HACKNEY On Music, Brands, Data and Storytelling 45 MUSIC IN IRAN A Personal Experience 49 HARTWIG MASUCH 10 Songs that Helped Create the New BMG 55 PROGRAMME REGISTER SESSIONS 59 SHOWCASES 65 the AWARDS 68 official app MEETINGS 68 Available on the App Store and Google Play NETWORKING 69 IMPRINT 76 PARTNERS 78 Meet us in Hamburg in September! Coverphoto: Camille Hackney, speaker at „Sync Faster – Sync Different and board member of ANCHOR 2017. © Grayson Dansic Contact Scandinavia - Esben Christensen Contact GAS - Sarah Schwaab [email protected] [email protected] 3 _ EDITORIAL DEAR CONFERENCE ATTENDEES, DEAR FRIENDS, we‘re delighted you have made it back to Hamburg once again this year for what is now the 12th edition of the Reeperbahn Festival. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K [x] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 . OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition Period from to . Commission file number 001-37713 eBay Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 77-0430924 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 2025 Hamilton Avenue San Jose, California 95125 (Address of principal (Zip Code) executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (408) 376-7008 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of exchange on which registered Common stock The Nasdaq Global Select Market 6.00% Notes due 2056 The Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes [x] No [ ] Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes [ ] No [x] Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Ebay's 2018 Annual Report

To our stockholders, As the Board Chairman, I continue to be proud of the meaningful impact eBay makes around the globe. With every buyer we delight and every seller we empower, we manifest our belief that technology and commerce can be forces for good. As I reflect on 2018, I see an eBay that is evolving to strengthen its business for the next 25 years. In 2018, we grew our active buyer base to 179 million, drove $95 billion in Global Merchandise Volume (GMV) and delivered record earnings. As evidence of our leaders’ continued confidence in eBay’s future, we returned $4.5 billion of capital to shareholders through the repurchase of common stock. I’m deeply proud of the decisions our Board and leadership team made in response to the challenges of positioning an established yet dynamic and innovative technology business to thrive over the long term. We made investments that set up the company for future success, focusing people and resources on our priority initiatives: buyer growth, conversion, payments and advertising. And we adjusted revenue and GMV expectations accordingly. As we shape eBay, I feel fortunate to work with such a stellar and diverse cross-section of leaders. On behalf of the entire Board, thank you for your ongoing support of eBay and our mission. With your help, we’ll continue to galvanize inspiration and economic opportunity around the world. Thomas Tierney Chairman of the Board To Our Stockholders, The past year has brought remarkable challenges and opportunities for both the technology industry and for eBay. It was a year of reckoning for many consumer tech companies, with a breakout of societal issues around privacy, trust, trade and immigration. -

Collaborative Economy in Tourism in Latin America the Case of Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Mexico Clausen, Helene Balslev; Velázquez, Mario

Aalborg Universitet Collaborative Economy in Tourism in Latin America The case of Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Mexico Clausen, Helene Balslev; Velázquez, Mario Published in: Collaborative Economy and Tourism DOI (link to publication from Publisher): 10.1007/978-3-319-51799-5_16 Publication date: 2017 Document Version Accepted author manuscript, peer reviewed version Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Clausen, H. B., & Velázquez, M. (2017). Collaborative Economy in Tourism in Latin America: The case of Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Mexico. In D. Dredge, & S. Gyimóthy (Eds.), Collaborative Economy and Tourism: Perspectives, Politics, Policies and Prospects (pp. 271-284). Springer. Springer Tourism on the Verge https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51799-5_16 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 25, 2021 Chapter 16 Collaborative Economy in Tourism in Latin America: The case of Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Mexico Helene Balslev Clausen and Mario Velázquez García Accepted chapter for “Tourism and the Collaborative Economy”, Springer Tourism on the Verge Series, London Abstract This chapter addresses collaborative economy in four Latin American countries: Argentina, Colombia, Chile and Mexico. -

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS

Pan Macmillan AUTUMN CATALOGUE 2021 PUBLICITY CONTACTS General enquiries [email protected] Alice Dewing FREELANCE [email protected] Anna Pallai Amy Canavan [email protected] [email protected] Caitlin Allen Camilla Elworthy [email protected] [email protected] Elinor Fewster Emma Bravo [email protected] [email protected] Emma Draude Gabriela Quattromini [email protected] [email protected] Emma Harrow Grace Harrison [email protected] [email protected] Jacqui Graham Hannah Corbett [email protected] [email protected] Jamie-Lee Nardone Hope Ndaba [email protected] [email protected] Laura Sherlock Jess Duffy [email protected] [email protected] Ruth Cairns Kate Green [email protected] [email protected] Philippa McEwan [email protected] Rosie Wilson [email protected] Siobhan Slattery [email protected] CONTENTS MACMILLAN PAN MANTLE TOR PICADOR MACMILLAN COLLECTOR’S LIBRARY BLUEBIRD ONE BOAT MACMILLAN Nine Lives Danielle Steel Nine Lives is a powerful love story by the world’s favourite storyteller, Danielle Steel. Nine Lives is a thought-provoking story of lost love and new beginnings, by the number one bestseller Danielle Steel. After a carefree childhood, Maggie Kelly came of age in the shadow of grief. Her father, a pilot, died when she was nine. Maggie saw her mother struggle to put their lives back together. As the family moved from one city to the next, her mother warned her about daredevil men and to avoid risk at all cost. Following her mother’s advice, and forgoing the magic of first love with a high-school boyfriend who she thought too wild, Maggie married a good, dependable man. -

Competition Issues in the UK TV Advertising Trading Mechanism

Redacted version for publication Competition issues in the UK TV advertising trading mechanism ITV plc response to Ofcom Consultation of 10 June 2011 REDACTED VERSION FOR PUBLICATION REDACTIONS ARE MARKED BY A [] SYMBOL 3 August 2011 508948521 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. Introduction 1 2. Industry Background 1 3. No reasonable grounds for reference 2 4. Discretion not to refer 6 PART A - NO REASONABLE GROUNDS FOR SUSPECTING COMPETITIVE HARM 9 5. The market for TV advertising cannot be viewed in isolation 9 6. The TV advertising market is highly competitive 18 7. No evidence of harm to advertisers 21 8. No evidence of harm to consumers – as viewers 25 9. No evidence of harm to consumers – as purchasers of advertised goods 28 10. The current trading model 30 11. International comparison 40 PART B - OFCOM SHOULD IN ANY EVENT EXERCISE DISCRETION NOT TO REFER 46 12. Ofcom discretion 46 13. Scale of the problem 47 14. No reasonable chance that remedies will be available 48 15. Prolonged uncertainty 52 16. Disproportionate impact on advertising funded broadcasters 53 17. Timing is wholly inappropriate – market is changing anyway 56 18. Conclusions 61 Annex A – Cross reference table to responses to Ofcom questions 63 Annex B – The Growth of Digital Marketing 65 1. Introduction 65 2. Technological changes 66 3. Key features of consumer usage of online and mobile technology and information services 70 4. Key implications of these changes 76 Annex C – The Markets for Viewers and Content 84 1. The UK market for viewers is highly competitive 84 2. Viewers particularly value original UK TV content 85 3. -

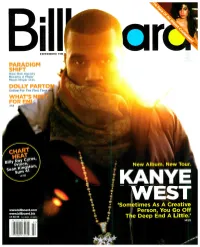

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal a Publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA SPRING 2011 | VOL. 22 | NO. 1 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Inside • Holocaust-Era Art Repatriation Claims • Time for a Change in Athletes’ Morals Clauses • The Performance Rights Act • Fair Market Value and Buyer’s Premium for Estate Tax • New York Museum Deaccessioning Purposes • EASL Annual Meeting • Lenz v. Universal Music Corporation • License v. Sale • Model Rules of Professional Conduct and Ethical Problems • Team Players and Individual Free-Speech Rights for Attorney-Agents Representing Professional Athletes • Copyright and Modern Art • Copyright Law for Dance Choreography • Florida Statute § 760.08 • Glory, Heartbreak, and Nostalgia of the Brooklyn Dodgers WWW.NYSBA.ORG/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION From the NYSBA Book Store > NEW! Counseling Content Providers in the Digital Age A Handbook for Lawyers For as long as there have been printing presses, there have been accusations of libel, invasion of privacy, intellectual property infringements and a variety of other torts. Now that much of the content reaching the public is distributed over the Internet, television (including cable and satellite), radio and fi lm as well as in print, the fi eld of pre-publication review has become more complicated and more important. Counseling Content Providers in the Digital Age provides an overview of the issues content reviewers face repeatedly. EDITORS Kathleen Conkey, Esq. Counseling Content Providers in the Digital Age was written Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. and edited by experienced media law attorneys from California Pamela C. Jones, Esq. and New York. -

Slides for That's the Ticket

Introduction Mamie Kresses Attorney FTC Division of Advertising Practices Things to Know • You must go through security every time you return to the building • Return badge and lanyard before you leave • In the event of emergency, follow instructions provided over PA • In the event of evacuation go to assembly area • Event will be photographed, webcast, and recorded • Restrooms are just outside conference room • Cafeteria is open for lunch • Food and drink are not permitted in the auditorium • #FTCticket Welcoming Remarks Rebecca K. Slaughter Commissioner Federal Trade Commission Keynote Address Eric Budish Professor of Economics The University of Chicago Booth School of Business How to Fix the Market for Event Tickets Eric Budish Professor of Economics University of Chicago, Booth School of Business First scalped ticket: Sept 17, 1986 (Mets clinch) FTC Workshop “That’s the Ticket” on Consumer Protection Issues in the Ticket Market Charles Dickens, Nov 1867 Boston, November 1867 • “... But the crowd out in the cold was a most patient, orderly and gentlemanly crowd, and seemed determined to be jolly and good-natured under any circumstances.” • “Jokes were cracked, some very good and some very poor; quotations from Dickens were made, some apt and others forced…” • “Everything in the sale of tickets within the store seemed to be conducted with entire fairness. The limit was set at forty-eight tickets to one person— twelve course tickets—so as to prevent, as much as possible, ticket speculating.” • “But this was not entirely avoided. Speculators were on the streets and in the hotels selling tickets readily for $10 and $15 each for the opening night, and a few as high as $20 each. -

Final Undertakings

COMPLETED ACQUISITION BY PUG LLC (viagogo) OF THE STUBHUB BUSINESS OF EBAY INC. Final Undertakings given by PUGNACIOUS ENDEAVORS, INC., PUG LLC, and StubHub, Inc., StubHub (UK) Limited, StubHub Europe S.à.r.l., StubHub India Private Limited, StubHub International Limited, StubHub Taiwan Co., Ltd., StubHub GmbH, and Todoentradas, S.L. (StubHub Group) to the Competition and Markets Authority pursuant to section 82 of the Enterprise Act 2002 Background A. On 13 February 2020, PUG LLC (PUG), a subsidiary of Pugnacious Endeavors, Inc. (viagogo) purchased the entire issued share capital of StubHub, Inc., StubHub (UK) Limited, StubHub Europe S.à.r.l., StubHub India Private Limited, StubHub International Limited, StubHub Taiwan Co., Ltd., StubHub GmbH, and Todoentradas, S.L. (together, StubHub Group) (the Merger). B. On 7 February 2020, the Competition and Markets Authority (the CMA) made an initial enforcement order (IEO) pursuant to section 72(2) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act) for the purpose of preventing pre-emptive action in accordance with that section. On 30 March 2020, the CMA issued directions under the IEO for the appointment of a monitoring trustee in order to monitor and ensure compliance with the IEO. C. On 25 June 2020, the CMA, in accordance with section 22(1) of the Act, referred the Merger to a group of CMA panel members (the Reference) to determine, pursuant to section 35 of the Act: (i) whether a relevant merger situation has been created; and (ii) if so, whether the creation of that situation has resulted, or may be expected to result, in a substantial lessening of competition (SLC) in any market or markets in the United Kingdom (UK) for goods or services.