The Pearl Harbor Attack: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matson Foundation 2014 Manifest

MATSON FOUNDATION 2014 MANIFEST THE 2014 REPORT OF THE CHARITABLE SUPPORT AND COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES OF MATSON, INC. AND ITS SUBSIDIARIES IN HAWAII, THE PACIFIC, AND ON THE U.S. MAINLAND. MESSAGE FROM THE CEO One of Matson’s core values is to contribute positively to Matson Foundation 2014 Leadership the communities in which we work and live. It is a value our employees have generously demonstrated throughout Pacific Committee our long, rich history, and one characterized by community Chair, Gary Nakamatsu, Vice President, Hawaii Sales service and outreach. Whether in Hilo, Hawaii or Oakland, Vic Angoco Jr., Senior Vice President, Pacific California or Savannah, Georgia, our employees have guided Russell Chin, District Manager, Hawaii Island Jocelyn Chagami, Manager, Industrial Engineering our corporate giving efforts to a diverse range of causes. Matt Cox, President & Chief Executive Officer While we were able to show our support in 2014 for 646 Len Isotoff, Director, Pacific Region Sales organizations that reflect the broad geographic presence of Ku’uhaku Park, Vice President, Government & Community Relations our employees, being a Hawaii-based corporation which has Bernadette Valencia, General Manager, Guam and Micronesia served the Islands for over 130 years, most of our giving was Staff: Linda Howe, [email protected] - directed to this state. In total, we contributed $1.8 million Ka Ipu ‘Aina Program Staff: Keahi Birch in cash and $140,000 of in-kind support. This includes two Adahi I ‘Tano Program Staff (Guam): Gloria Perez special environmental partnership programs in Hawaii and Guam, Ka Ipu ‘A- ina and Adahi I Tano’, respectively. Since its Mainland Committee inception in 2001, Ka Ipu ‘A- ina has generated over 1,000 Chair, David Hoppes, Senior Vice President, Ocean Services environmental clean-up projects in Hawaii and contributed Patrick Ono, Sales Manager, Pacific Northwest* Gregory Chu, Manager, Freight Operations, Pacific Northwest** over $1 million to Hawaii’s charities. -

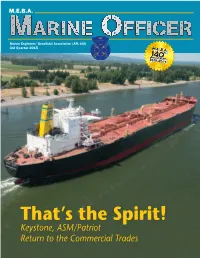

2015 3Rd Quarter

M.E.B.A. Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (AFL-CIO) 3rd Quarter 2015 That’s the Spirit! Keystone, ASM/Patriot Return to the Commercial Trades Faces around the Fleet Another day on the MAERSK ATLANTA, cutting out a fuel pump in the Red Sea. From left to right are 1st A/E Bob Walker, C/E Mike Ryan, 3rd A/E Clay Fulk and 2nd A/E Gary Triguerio. C/E Tim Burchfield had just enough time to smile for shutterbug Erin Bertram (Houston Branch Agent) before getting back to overseeing important operations onboard the MAERSK DENVER. The vessel is a Former Alaska Marine Highway System engineer and dispatcher Gene containership managed by Maersk Line, Ltd that is Christian took this great shot of the M/V KENNICOTT at Vigor Industrial's enrolled in the Maritime Security Program. Ketchikan, Alaska yard. The EL FARO sinking (ex-NORTHERN LIGHTS, ex-SS PUERTO RICO) was breaking news as this issue went to press. M.E.B.A. members past and present share the grief of this tragedy with our fellow mariners and their families at the AMO and SIU. On the Cover: M.E.B.A. contracted companies Keystone Shipping and ASM/Patriot recently made their returns into the commercial trades after years of exclusively managing Government ships. Keystone took over operation of the SEAKAY SPIRIT and ASM/Patriot is managing the molasses/sugar transport vessel MOKU PAHU. Marine Officer The Marine Officer (ISSN No. 10759069) is Periodicals Postage Paid at The Marine Engineers’ Beneficial Association (M.E.B.A.) published quarterly by District No. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 San Francisco, California * Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at San Francisco, CA, 1893-1953. M1410. 429 rolls. Boll Contents 1 May 1, 1893, CITY OF PUBLA-February 7, 1896, GAELIC 2 March 4, 1896, AUSTRALIA-October 2, 1898, SAN BLAS 3 October 26, 1898, ACAPULAN-October 1, 1899, INVERCAULA 4 November 1, 1899, CITY OF PUBLA-October 31, 1900, CURACAO 5 October 31, 1900, CURACAO-December 23, 1901, CITY OF PUEBLO 6 December 23, 1901, CITY OF PUEBLO-December 8, 1902, SIERRA 7 December 11, 1902, ACAPULCO-June 8, 1903, KOREA 8 June 8, 1903, KOREA-October 26, 1903, RAMSES 9 October 28, 1903, PERU-November 25, 1903, HONG KONG MARU 10 November 25, 1903, HONG KONG MARU-April 25, 1904, SONOMA 11 May 2, 1904, MELANOPE-August 31, 1904, ACAPULCO 12 August 3, 1904, LINDFIELD-December 17, 1904, MONGOLIA 13 December 17, 1904, MONGOLIA-May 24, 1905, MONGOLIA 14 May 25, 1905, CITY OF PANAMA-October 23, 1905, SIBERIA 15 October 23, 1905, SIBERIA-January 31, 1906, CHINA 16 January 31, 1906, CHINA-May 5, 1906, SAN JUAN 17 May 7, 1906, DORIC-September 2, 1906, ACAPULCO 18 September 2, 1906, ACAPULCO-November 8, 1906, KOREA Roll Contents Roll Contents 19 November 8, 1906, KOREA-Feburay 26, 1907, 56 April 11, 1912, TENYO MARU-May 28, 1912, CITY MONGOLIA OF SYDNEY 20 March 3, 1907, CURACAO-June 7, 1907, COPTIC 57 May 28, 1912, CITY OF SYDNEY-July 11, 1912, 21 May 11, 1907, COPTIC-August 31, 1907, SONOMA MANUKA 22 September 1, 1907, MELVILLE DOLLAR-October 58 July 11, 1912, MANUKA-August -

1962 November Engineers News

OPERATING ENGINEERS LOCI( 3 ~63T o ' .. Vol. 21 - No. 11 SANFRA~CISCO, ~AliFORN!~ . ~151 November1 1962 LE ·.·. Know Your . Friends greem~l1t on _And Your Enemies On.T o Trusts ;rwo ·trust instruni.ents for union-management' joint ad· ministration of Novel;llber 6 is Election Pay-,-a day that is fringe benefits negotiated by Operating En. gineers to e very American of voting age, but particularly Local 3 in the last industry agreement were· agreed upon in October. ' · ._. to men:tbers of Ope•rating Engineers Local 3. · The • -/ trust in~truments wen~ for the Operating Engineers · Voting~takirig a perso~al hand in the selection of the · Apprentice & J o urn e y m an ' · . men who w_ill ·make our laws an:d administer them on the . Training Fund and -for Health trust documents, Local 3 Bus. val~ ious levels of gov~minent-is a privilege· our~· aricestors· & Welfare benefits for pensioned Mgr. Al Clem commented: "The - -· fought: for. and thaC we . ~hould trel(lsure. But for most of Engineers. Negotiating Committee's discus- ·the . electorate. it's · simply that, a free man's privilege; not . · Agreement on the two trusts sions with the employers were an obligati_on. · . · . came well in advance_of January cordial and cooperative. We are - For members o{ Local 3, P,owev~r, _ lt's some•thing more 1, WB3, de~dlines which provided gratified that our members will ) han that; it comes cl(!?~r· t.9 b~, ing .<rb!ndiilg obligation. - that if union and employer .nego- be able to ·get the penefit of .· _If you'r~-::~dtpi- 1se f~y ti1i{ 'statement;· it might be in tiators couldn't acrree on either these trusts without delay and or der .::to"'ask:. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

CHAPTER FIVE Arrival in America

CHAPTER FIVE Arrival in America 'Neath the Golden Gate to California State We arrived on a morning fair. Near the end of the trip, we stayed aboard ship, We were still in the Navy's care I was the young wife, embarked on a new life Happiness mixed with confusion. I'd not seen for a year the one I held dear Would our love still bloom in profusion? (Betty Kane, 'The War Bride', November 2001 )1 The liner SS Monterey arrived in San Francisco on March 5, 1946, with 562 Australian and New Zealand war brides and their 253 children on board. A journalist from The Sydney Morning Herald was there to report that 'scores' of husbands were waiting on the dock, and that 'true to the reputation they established in Australia as great flower givers, nearly all the husbands clutched huge boxes of blooms' for their brides and fiancees.2 'Once the ship was cleared by the health authorities', it was reported, 'the husbands were allowed aboard and there were scenes in the best Hollywood manner.'3 It was a 'journalists' day out', according to the newspaper, and a boatload' of press and movie photographers and special writers from all the major news services and Californian newspapers went in an army tugboat to meet the MontereyA Betty Kane, 'The War Bride', in Albany Writers' Circle No. 19. A Collection of Short Stories and Poetry by the Writers of Albany, November Issue, Denmark Printers, Albany, WA, 2001, pp. 36 and 37. " The Sydney Morning Herald, March 6. 1946, p. -

Shipping and Waterfront News Dally Published Ovory Afternoon (Except Sunday) by Tho Hawaiian Star by W

THE HAWAIIAN STAR DAILY AND SEMI-WEEKL- Shipping And Waterfront News Dally published ovory afternoon (except Sunday) by tho Hawaiian Star BY W. H. CLARKE. Newspaper Association, Ltd., McCand loss Dulldlng, Bethel ttreet, Hono (Additional Shipping on Page Five.) lulu, T. II. t i THE MAILS. I nolulu from Yokohama, August 1. Enteral at tho postofflce at Honolulu as second class mall matter. From San Francisco. Honolulnu. ANDREW welch. Am i.ir fn.' ugust S. Honolulu from San Francisco July NO SEASICKNESS ON THIS VESSEL SUBSCRIPTION KATKB, PAYABLE IN ADVANCE. To tho Orient, per Manchuria, Au- - 23. gust S. Dally, mywhero In the Islands, per. month $ .76, DENICIA, Am. bv... ar. Gray's Harbor Dally, anywhere In the Islnnds, three months 2.00. To San Francisco, per Mongolia. from Illlo Juno 2. Philadelphia Ledger: The gigantic port C Dally, auywhero m the Islands, six months 4.00. August C. at o'clock Sunday morning from HERTHA, German bk., from Kahului 900-fo- From steamer Imporator, now being tho Orient. For hero she has 1300 Dally, anywhere In the iBlunds, one year 8.00. tho Orient, Au ar. Gray's Harbor, May 10. 0. built ut Hamburg, Germany, for the tons of cargo, Dally, to foreign countries, one year 12.00. gust DOItEALIS, Am. but, no mention was schr., for Hllo from Hnmburg-Amorlca- n Semi-Weekl- y, anywhero In tho Islands, one year 2.00. From Line, will, when nindo of tho Australia, August Grny's Harbor, July 22. number of passengers to Semi-Week- ly to Foreign countrl es, one year 3.00. -

Download Full Book

Fighting for Hope Jefferson, Robert F. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Jefferson, Robert F. Fighting for Hope: African American Troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and Postwar America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3504. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3504 [ Access provided at 26 Sep 2021 09:46 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Fighting for Hope war/society/culture Michael Fellman, Series Editor Fighting for Hope *** African American Troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and Postwar America robert f. jefferson The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2008 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 246897531 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jeªerson, Robert F., 1963– Fighting for hope : African American troops of the 93rd Infantry Division in World War II and postwar America / Robert F. Jeªerson. p. cm.—(War/society/culture) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-8018-8828-1 (hbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-8018-8828-x (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. World War, 1939–1945—Participation, African American. 2. World War, 1939–1945—Campaigns—Oceania. 3. World War, 1939–1945—Veterans— United States—Social conditions. 4. United States. Army. Division, 93rd. 5. United States. Army—African American troops. -

The Hawaii Nisei Story: Creating a Living Digital Memory

The Hawaii Nisei Story: Creating a Living Digital Memory Paper Presented at Media in Transition 6 Conference, April 24-26, 2009 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Shari Y. Tamashiro Kapi’olani Community College, University of Hawai’i “Rarely has a nation been so well served by a people it had so ill treated.” – President Bill Clinton. Abstract: The Hawaii Nisei Story, a Web-based exploration of the experiences of local Americans of Japanese Ancestry leading up to, during and following the Second World War, comprises the life stories of Hawaii-born Nisei (second generation Japanese-Americans) veterans. Some well-known, some less so, these stories are deepened, complemented and complicated by the seldom heard stories of the veterans' wives and families. Read their stories at: http://nisei.hawaii.edu The project bridged the print and digital worlds. Thomas H. Hamilton Library established the Japanese American Veterans Collection to collect, store and catalog official papers, letters, photographs and other materials relating to the veterans’ WWII experiences. To document and place these wartime experiences in socio-historical context, the University of Hawaii’s Center for Oral History recorded and processed thirty life history interviews. Kapiolani Community College utilized oral histories, a myriad of primary source materials and the technology tools available to go outside the realm of traditional linear narrative and create a digital collection that serves a living digital memory. The Nisei Legacy The Nisei legacy is significant and still relevant today. Their experiences are a powerful reminder of the importance of civil liberties and civil rights in a democratic society.1 This community-based project was initiated and funded by the University of Hawaii in response to requests made by Hawaii Nisei veterans for the university to not only preserve but to tell their life stories. -

Colonel M. M. Magruder

Property of MARINE CORI'S HIS SEP 3 8 Fleece 1-19E;otu VOL. VII, No. 35 U. S. MARINE CORPS AIR STATION, KANEOHE BAY, T. H. Friday, August 22, 1958 COLONEL M. M. MAGRUDER ASSUMES COMMAND HERE A colorful and experienced Ma- new duties at the Marine Corps Air thereby climaxing a tour of duty rine Aviator, Colo/fel Marion M. Ma- Station, El Toro, Calif. which began here in October 1956. gruder assumed command of the Air As the band sounded attention Many civic and military cligni- Station here during formal change signaling the beginning of the cere- taxies, and friends of both Col, Cram of command ceremonies Tuesday. monies, a battalion of Marines stood and Col. Magruder were present to Col. Magruder relieved Colonel at rigid attention to welcome a new witness the ceremonies. For the past Jack R. Craw who will depart for commander, and bid farewell to week, Col. and Mrs. Cram have been the mainland tomorrow, aboard their departing commander, busy attending many Aloha parties the S.S. Lurline and will assume The actual change of command given in their honor. took place when Lt.Col. Charles Prior to assuming his new com- Kimak, commander of troops for mand here, Col. Magruder served the ceremonial parade and review as Deputy Chief of Staff, Head- Fewer Inoculations gave the order, "Publish the order, quarters, Fleet Marine Force Pacific, Sir." Lt. Holly Clayson, parade ad- at Camp H. M. Smith. jutant then read the order signed Another highlight of the parade Slated For Military by the Commandant of the Marine ' and review was the presentation of Col. -

LEVY's Office 403 Stangewald Time Scents, Honolulu

iSIiil;i&3 ti ila g ..... , - uHBf'T'tWij - " T.TfS-- i &??p'3PwT3f?SH .j--- f " 8 ' fc BrflNO BULLSTIN. HONOLULU, T. H., TUESDAY,' JAN. 26. 1&10. - r v- -"- t'J 3f " -" " i IflK ?- I I. i ,...- t 7?-)- , & PROVED-B- Oceanic Steamship Company , MtOMlP Baldwin bv authority, THIRD RECITAL Y I LIMITED. twk t RESOLUTION. ' - . V." I i BY TEST !W '! v A . -- J- io. nraiflKBa awt H!m:p.tor9. Honolulu, T. H., January 18, 1910, TALENT j X 1111C X CVU1&ii President LGfL H$ U.kJ. i ViaillCUA v H. F, Baldwin , BR IT RESOLVED by the Bonxt ut J. B. Castle. .Vice President Supervisors of the City and County I T'ie steamers of this line will arrive and leave this port ai hereunder; M.rAlexander. l K W. ...'"..'.. 7. of Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, Rial Pure Prepared Paint has Leave S. F, Arrive Hon. Leave Hon. Anive S. F. BISHOP GO, ..... .3' Vice Pres. the" sum ol EiajHT HUNDRED Musical Reading By Mrs. IK' JAN. 22 JAN. 28 JAN. 12 , JAN. 18 & P.' been l J. Cooke. ($800.00) DOLLARS be and the same 1 proved by years of use " tKU- - Third Vv -1 ' nager Is hereby (Ion. "", 1AIXUI appropriated out of the Waterhouse Will in Honolulu. No other J. Water'-.- ' T.'.attrer eral Fund for tho purchase of n team paint 'Connects at Honolulu with C. A. Line, leaving Honolulu (or Aus- E. E. Proton. - ot horses for the Honolulu Fire De- can equal in qual- Commercial and Trav- ' Be, Featjurc it wearing tralia Jan. -

Imposing Ceremonies Hawaii Arrives at San Pedro

u 6 U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, June 21. Last 24 Hoars' Rainfall, trace SUGAR 96 DegTee Test Centrifugals, 4.40c. Per Ton, $88.00. Temperature, Max. 79; Min, 70. Weather, cloudy to fair. 83 Analysis Beets, Us. 4d. Per Ton, $88.00. ' KSTBlilHrih;U J'-.-i k. is vr i a Jk. W I IX I W m I- HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, MONDAY, JUNE 22, 1908. PRICE FIVE CENTS. ALII LAID TO REST WITH STANCH YACHT IMPOSING CEREMONIES HAWAII ARRIVES AT SAN PEDRO French Deputies and Senators Who Voted for Separation of Church and State Are Excommunicated Anna Gould and Her Prince Go to England. 4 f (Associated Prea Cablegram.) SAN PEDRO, June 22. The yacht Hawaii arrived here last night after an uneventful voyage. The Hawaii Yacht Club's Transpa- - The Hawaiian entry In the first cific entry, Hawaii, was cabled lant Transpacific yacht ra-J- e held two years night as having arrived at San Pedro, ago. La Paloma, leit here on April 14, She left here on June 2 about two 1906, at 2 p. m., and arrived at Ban o'clock and has made the 2300-mi- le trip Francisco on May 13 at 7 p. m., thm in 19 days, averaging 115 knots a day. (Continued on Taga Three.) THE CHURCH STRETCHES FORTH HER MAILED HAND : ; ' 2 W V;-- - -- - V' "J,-:-- . PARIS; June 22. The Deputies and Senators who voted for the separation of church and state have been excommunicated. Action in the determined purpose of the French government antl the French neoole to secure complete separation of church and state - j ' has been going1 on for abotitstnree years.