Oral History of Alvy Ray Smith; 2010-05-27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2018 Alumni Magazine

University Advancement NONPROFIT ORG PO Box 2000 U.S. POSTAGE Superior, Wisconsin 54880-4500 PAID DULUTH, MN Travel with Alumni and Friends! PERMIT NO. 1003 Rediscover Cuba: A Cultural Exploration If this issue is addressed to an individual who no longer uses this as a permanent address, please notify the Alumni Office at February 20-27, 2019 UW-Superior of the correct mailing address – 715-394-8452 or Join us as we cross a cultural divide, exploring the art, history and culture of the Cuban people. Develop an understanding [email protected]. of who they are when meeting with local shop keepers, musicians, choral singers, dancers, factory workers and more. Discover Cuba’s history visiting its historic cathedrals and colonial homes on city tours with your local guide, and experience one of the world’s most culturally rich cities, Havana, and explore much of the city’s unique architecture. Throughout your journey, experience the power of travel to unite two peoples in a true cultural exchange. Canadian Rockies by Train September 15-22, 2019 Discover the western Canadian coast and the natural beauty of the Canadian Rockies on a tour featuring VIA Rail's overnight train journey. Begin your journey in cosmopolitan Calgary, then discover the natural beauty of Lake Louise, Moraine Lake, and the powerful Bow Falls and the impressive Hoodoos. Feel like royalty at the grand Fairmont Banff Springs, known as the “Castle in the Rockies,” where you’ll enjoy a luxurious two-night stay in Banff. Journey along the unforgettable Icefields Parkway, with a stop at Athabasca Glacier and Peyto Lake – a turquoise glacier-fed treasure that evokes pure serenity – before arriving in Jasper, nestled in the heart of the Canadian Rockies. -

Blue Screen Matting

Blue Screen Matting Alvy Ray Smith and James F. Blinn Microsoft Corporation ABSTRACT allowed to pass through and illuminate those parts desired but is blocked everywhere else. A holdout matte is the complement: It is A classical problem of imaging—the matting problem—is separa- opaque in the parts of interest and transparent elsewhere. In both tion of a non-rectangular foreground image from a (usually) rectan- cases, partially dense regions allow some light through. Hence gular background image—for example, in a film frame, extraction of some of the color film image that is being matted is partially illu- an actor from a background scene to allow substitution of a differ- minated. ent background. Of the several attacks on this difficult and persis- The use of an alpha channel to form arbitrary compositions of tent problem, we discuss here only the special case of separating a images is well-known in computer graphics [9]. An alpha channel desired foreground image from a background of a constant, or al- gives shape and transparency to a color image. It is the digital most constant, backing color. This backing color has often been equivalent of a holdout matte—a grayscale channel that has full blue, so the problem, and its solution, have been called blue screen value pixels (for opaque) at corresponding pixels in the color image matting. However, other backing colors, such as yellow or (in- that are to be seen, and zero valued pixels (for transparent) at creasingly) green, have also been used, so we often generalize to corresponding color pixels not to be seen. -

Pixar's 22 Rules of Story Analyzed

PIXAR’S 22 RULES OF STORY (that aren’t really Pixar’s) ANALYZED By Stephan Vladimir Bugaj www.bugaj.com Twitter: @stephanbugaj © 2013 Stephan Vladimir Bugaj This free eBook is not a Pixar product, nor is it endorsed by the studio or its parent company. Introduction. In 2011 a former Pixar colleague, Emma Coats, Tweeted a series of storytelling aphorisms that were then compiled into a list and circulated as “Pixar’s 22 Rules Of Storytelling”. She clearly stated in her compilation blog post that the Tweets were “a mix of things learned from directors & coworkers at Pixar, listening to writers & directors talk about their craft, and via trial and error in the making of my own films.” We all learn from each other at Pixar, and it’s the most amazing “film school” you could possibly have. Everybody at the company is constantly striving to learn new things, and push the envelope in their own core areas of expertise. Sharing ideas is encouraged, and it is in that spirit that the original 22 Tweets were posted. However, a number of other people have taken the list as a Pixar formula, a set of hard and fast rules that we follow and are “the right way” to approach story. But that is not the spirit in which they were intended. They were posted in order to get people thinking about each topic, as the beginning of a conversation, not the last word. After all, a hundred forty characters is far from enough to serve as an “end all and be all” summary of a subject as complex and important as storytelling. -

Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing

Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing Technical Memo 7 Alvy Ray Smith August 15, 1995 Abstract The history of digital image compositing—other than simple digital imple- mentation of known film art—is essentially the history of the alpha channel. Dis- tinctions are drawn between digital printing and digital compositing, between matte creation and matte usage, and between (binary) masking and (subtle) mat- ting. The history of the integral alpha channel and premultiplied alpha ideas are pre- sented and their importance in the development of digital compositing in its cur- rent modern form is made clear. Basic Definitions Digital compositing is often confused with several related technologies. Here we distinguish compositing from printing and matte creation—eg, blue-screen matting. Printing v Compositing Digital film printing is the transfer, under digital computer control, of an im- age stored in digital form to standard chemical, analog movie film. It requires a sophisticated understanding of film characteristics, light source characteristics, precision film movements, film sizes, filter characteristics, precision scanning de- vices, and digital computer control. We had to solve all these for the Lucasfilm laser-based digital film printer—that happened to be a digital film input scanner too. My colleague David DiFrancesco was honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Art and Sciences last year with a technical award for his achievement on the scanning side at Lucasfilm (along with Gary Starkweather). Also honored was Gary Demos for his CRT-based digital film scanner (along with Dan Cam- eron). Digital printing is the generalization of this technology to other media, such as video and paper. -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

MONSTERS INC 3D Press Kit

©2012 Disney/Pixar. All Rights Reserved. CAST Sullivan . JOHN GOODMAN Mike . BILLY CRYSTAL Boo . MARY GIBBS Randall . STEVE BUSCEMI DISNEY Waternoose . JAMES COBURN Presents Celia . JENNIFER TILLY Roz . BOB PETERSON A Yeti . JOHN RATZENBERGER PIXAR ANIMATION STUDIOS Fungus . FRANK OZ Film Needleman & Smitty . DANIEL GERSON Floor Manager . STEVE SUSSKIND Flint . BONNIE HUNT Bile . JEFF PIDGEON George . SAM BLACK Additional Story Material by . .. BOB PETERSON DAVID SILVERMAN JOE RANFT STORY Story Manager . MARCIA GWENDOLYN JONES Directed by . PETE DOCTER Development Story Supervisor . JILL CULTON Co-Directed by . LEE UNKRICH Story Artists DAVID SILVERMAN MAX BRACE JIM CAPOBIANCO Produced by . DARLA K . ANDERSON DAVID FULP ROB GIBBS Executive Producers . JOHN LASSETER JASON KATZ BUD LUCKEY ANDREW STANTON MATTHEW LUHN TED MATHOT Associate Producer . .. KORI RAE KEN MITCHRONEY SANJAY PATEL Original Story by . PETE DOCTER JEFF PIDGEON JOE RANFT JILL CULTON BOB SCOTT DAVID SKELLY JEFF PIDGEON NATHAN STANTON RALPH EGGLESTON Additional Storyboarding Screenplay by . ANDREW STANTON GEEFWEE BOEDOE JOSEPH “ROCKET” EKERS DANIEL GERSON JORGEN KLUBIEN ANGUS MACLANE Music by . RANDY NEWMAN RICKY VEGA NIERVA FLOYD NORMAN Story Supervisor . BOB PETERSON JAN PINKAVA Film Editor . JIM STEWART Additional Screenplay Material by . ROBERT BAIRD Supervising Technical Director . THOMAS PORTER RHETT REESE Production Designers . HARLEY JESSUP JONATHAN ROBERTS BOB PAULEY Story Consultant . WILL CSAKLOS Art Directors . TIA W . KRATTER Script Coordinators . ESTHER PEARL DOMINIQUE LOUIS SHANNON WOOD Supervising Animators . GLENN MCQUEEN Story Coordinator . ESTHER PEARL RICH QUADE Story Production Assistants . ADRIAN OCHOA Lighting Supervisor . JEAN-CLAUDE J . KALACHE SABINE MAGDELENA KOCH Layout Supervisor . EWAN JOHNSON TOMOKO FERGUSON Shading Supervisor . RICK SAYRE Modeling Supervisor . EBEN OSTBY ART Set Dressing Supervisor . -

Frame by Frame

FRAME BY FRAME by Glen Ryan Tadych As we celebrate Thanksgiving and prepare Watching it as an adult though is a different experi- ences go, “What is this?!” And while this factor is for the holiday season, some of cinema’s most ence sure enough, as I’m able to understand how what made Toy Story memorable to most audiences Lasseter’s work on the short film and other TGG anticipated films prepare to hit theaters, most the adult themes are actually what make the film so upon leaving the theater, the heart of the film still projects landed him a full-time position as an notably Star Wars: The Force Awakens. This moving. lies beneath the animation, the impact of which is interface designer that year. However, everything past Wednesday, Disney and Pixar’s latest what makes Toy Story a classic. changed for TGG in 1986. computer-animated adventure, The Good Today, I see Toy Story as the Star Wars (1977) of Dinosaur, released nationwide to generally my generation, and not just because it was a “first” Toy Story’s legacy really begins with Pixar’s be- Despite TGG’s success in harnessing computer positive reception, but this week also marked for the film industry or a huge critical and commer- ginnings in the 1980s. Pixar’s story begins long be- graphics, and putting them to use in sequences another significant event in Pixar history: the cial success. Like Star Wars, audiences of all ages fore the days of Sheriff Woody and Buzz Lightyear, such as the stained-glass knight in Young Sherlock 20th anniversary of Toy Story’s original theatri- worldwide enjoyed and cherished Toy Story because and believe it or not, the individual truly responsible Holmes (1985), Lucasfilm was suffering financially. -

Richer Worlds for Next Gen Games: Data Amplification Techniques Survey

Richer Worlds for Next Gen Games: Data Amplification Techniques Survey Natalya Tatarchuk 3D Application Research Group ATI Research, Inc. Overview • Defining the problem and motivation • Data Amplification • Procedural data generation • Geometry amplification • Data streaming • Data simplification • Conclusion Overview • Defining the problem and motivation • Data Amplification • Procedural data generation • Geometry amplification • Data streaming • Data simplification • Conclusion Games and Current Hardware • Games currently are CPU-limited – Tuned until they are not GPU-limited – CPU performance increases have slowed down (clock speed hit brick walls) – Multicore is used in limited ways Trends in Games Today • Market demands larger, more complex game worlds – Details, details, details • Existing games already see increase in game data – Data storage progression: Floppies → CDs → DVDs – HALO2.0 - 4.2GB – HD-DVD/Blueray → 20GB [David Blythe, MS Meltdown 2005] Motivation • GPU performance increased tremendously over the years – Parallel architecture allows consumption of ever increasing amounts of data and fast processing – Major architectural changes happen roughly every 2 years – 2x speed increase also every 2 years – Current games tend to be • Arithmetic limited (shader limited) • Memory limited • GPUs can consume ever increasing amounts of data, producing high fidelity images – GPU-based geometry generation is on the horizon – Next gen consoles Why Not Just Author A Ton of Assets? • Rising development cost – Content creation is the bottleneck -

Downloaded for Storage and Display—As Is Common with Contemporary Systems—Because in 1952 There Were No Image File Formats to Capture the Graphical Output of a Screen

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title The random-access image: Memory and the history of the computer screen Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0b3873pn Journal Grey Room, 70(70) ISSN 1526-3819 Author Gaboury, J Publication Date 2018-03-01 DOI 10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. -

Hereby the Screen Stands in For, and Thereby Occludes, the Deeper Workings of the Computer Itself

John Warnock and an IDI graphical display unit, University of Utah, 1968. Courtesy Salt Lake City Deseret News . 24 doi:10.1162/GREY_a_00233 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/GREY_a_00233 by guest on 27 September 2021 The Random-Access Image: Memory and the History of the Computer Screen JACOB GABOURY A memory is a means for displacing in time various events which depend upon the same information. —J. Presper Eckert Jr. 1 When we speak of graphics, we think of images. Be it the windowed interface of a personal computer, the tactile swipe of icons across a mobile device, or the surreal effects of computer-enhanced film and video games—all are graphics. Understandably, then, computer graphics are most often understood as the images displayed on a computer screen. This pairing of the image and the screen is so natural that we rarely theorize the screen as a medium itself, one with a heterogeneous history that develops in parallel with other visual and computa - tional forms. 2 What then, of the screen? To be sure, the computer screen follows in the tradition of the visual frame that delimits, contains, and produces the image. 3 It is also the skin of the interface that allows us to engage with, augment, and relate to technical things. 4 But the computer screen was also a cathode ray tube (CRT) phosphorescing in response to an electron beam, modified by a grid of randomly accessible memory that stores, maps, and transforms thousands of bits in real time. The screen is not simply an enduring technique or evocative metaphor; it is a hardware object whose transformations have shaped the ma - terial conditions of our visual culture. -

Lights, Camera, Media Literacy! the PIXAR STORY by Leslie Iwerks

Lights, Camera, Media Literacy! THE PIXAR STORY By Leslie Iwerks When you hear the phrase or statement (“in quotes”), place a checkmark next to it. __1) “The art challenges technology. Technology inspires the art.” __2) “The best scientists and engineers are just as creative as the best storytellers.” __3) “This marriage of art and science was the combined dream of three men… the creative scientist Ed Catmull, the visionary entrepreneur Steve Jobs, and the talented artist John Lasseter.” __4) “The teachers at Cal Arts were none other than Disney’s legendary collaborators from the 1930’s known as “The Nine Old Men” who taught the essence of great character animation.” __5) “TRON, a live-action feature using the latest computer technology, was screened for employees at the [Disney] studio.” __6) “Computer animation excited me so much. I wasn’t excited about what I was seeing, but the potential I saw in all this.” __7) “If it had never been done before doesn’t mean it can’t be done.” __8) “…no one wanted to do it except for Lasseter.” __9) “He got fired, because, honestly, the studio didn’t know what to do with him.” __10) “During a lot of the early days, artists were frightened of the computer.” __11) “In the 1960’s, the University of Utah set up one of the first labs in computer graphics, headed by the top scientists in the field.” __12) “Here was a program in which there was art, science, programming altogether in one place, a new field. It was wide open. Just go out and discover things and explore right at the frontier.” __13) “Ed’s computer-animated film of his own left hand was the first step in the development of creating curved surfaces, wrapping texture around those surfaces, and eliminating jagged edges.” __14) “Alex Schure, the president of New York Tech, hired Ed to spearhead the new computer graphics department to develop paint programs and other tools to create art and animation using the computer. -

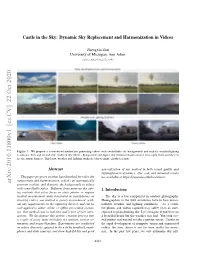

Castle in the Sky: Dynamic Sky Replacement and Harmonization in Videos

Castle in the Sky: Dynamic Sky Replacement and Harmonization in Videos Zhengxia Zou University of Michigan, Ann Arbor [email protected] Figure 1: We propose a vision-based method for generating videos with controllable sky backgrounds and realistic weather/lighting conditions. First and second row: rendered sky videos - flying castle and Jupiter sky (leftmost shows a frame from input video and the rest are the output frames). Third row: weather and lighting synthesis (day to night, cloudy to rainy). Abstract generalization of our method in both visual quality and lighting/motion dynamics. Our code and animated results This paper proposes a vision-based method for video sky are available at https://jiupinjia.github.io/skyar/. replacement and harmonization, which can automatically arXiv:2010.11800v1 [cs.CV] 22 Oct 2020 generate realistic and dramatic sky backgrounds in videos with controllable styles. Different from previous sky edit- 1. Introduction ing methods that either focus on static photos or require inertial measurement units integrated in smartphones on The sky is a key component in outdoor photography. shooting videos, our method is purely vision-based, with- Photographers in the wild sometimes have to face uncon- out any requirements on the capturing devices, and can be trollable weather and lighting conditions. As a result, well applied to either online or offline processing scenar- the photos and videos captured may suffer from an over- ios. Our method runs in real-time and is free of user inter- exposed or plain-looking sky. Let’s imagine if you were on actions. We decompose this artistic creation process into a beautiful beach but the weather was bad.