Servants' Pasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basis of a New Social Order

BASIS Of ANEW SOCIAl ORDER By S. Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi ACADEMY OF ISLAMIC RESEARCH & PUBLICATIONS LUCKNOW (INDIA) All Rights Rtserved ill favour of: Academy of Islamic Research and Publica.tions Tagore Mp.rg, Nadwatul Ulama, P. 0. Box No. ll9, Lucknow-22'6 Om' (India} S'fRlES NO. SS Printed at : NADWA PRESS Lucknow. (AP-NS: 60) BASIS OF A NEW SOCIAL ORDER Zakat which Islam has. enjoined upon Muslims marks Lhe lowest limit of the expression of human sympathy, kind lines and compassion. ft is a duty the disregard or violation of whicl1 is not in any circumstances tolerable to God. The Sliariat is emphatic in its insistence upon its observance. ft has prescribed it as an essential requirement of Faith for MusLims. But it they repent and establish worship and pay the poor-due, then they are your brethern. (-ix : 11 ) A person who abjures Zakat or declines wilfully to pay it will be deemed to .have forfeited the claim to be a Muslim. There will be no place for him in the fold of Tslam. Such were the men against whom Hazrat Abu Bakr had taken up arms and his action was supported universally by the Companions. Other Obligations On Wealth The holy prophet had, by 11is teachings and personal example, made it clear to his friends and Companions thac Zakat was not the be-all-and-end-all of monetary good- ( 2 doing. ft was not the highest form or uJcimatc stage of charity and generosity. Tn 1he words of tl1c holy Prophet. " Beyond question, there arc other obligations on wcalch aside of Zakat.'' It is related by Fatima Bint-i-Qais that once the Prophet was asked (or she herself:1sked him) about Zakar. -

Anthoney Udel 0060D

INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Spring 2018 © 2018 Cheryl Anthoney All Rights Reserved INCLUSION WITHOUT MODERATION: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATION BY RELIGIOUS GROUPS by Cheryl Mariani Anthoney Approved: __________________________________________________________ David P. Redlawsk, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Muqtedar Khan, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Stuart Kaufman, -

Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009)

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009) New Delhi 151 Printed at : Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Chairman: Mr. Justice G. N. Ray Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANIZATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPER Shri Vishnu Nagar Editors Guild of India, All India Nai Duniya, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Uttam Chandra Sharma All India Newspaper Editors’ Muzaffarnagar Conference, Editors Guild of India, Bulletin, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Vijay Kumar Chopra All India Newspaper Editors’ Filmi Duniya, Conference, Editors Guild of India, Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Sheetla Singh Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Janmorcha, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Ms. Suman Gupta Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Saryu Tat Se, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Editors of English Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Yogesh Chandra Halan Editors Guild of India, All India Asian Defence News, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri K. Sreenivas Reddy Indian Journalists Union, Working Visalaandhra, News Cameramen’s Association, Andhra Pradesh Press Association Shri Mihir Gangopadhyay Indian Journalists Union, Press Freelancer, (Ganguly) Association, Working News Bartaman, Cameramen’s Association West Bengal Shri M.K. Ajith Kumar Press Association, Working News Mathrubhumi, Cameramen’s Association, New Delhi Indian Journalists Union Shri Joginder Chawla Working News Cameramen’s Freelancer Association, Press Association, Indian Journalists Union Shri G. -

People of Ghazni

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs/ Province: Zabul April 13, 2009 Governor: Mohammad Ashraf Nasseri Provincial Police Chief: Colonel Mohammed Yaqoub Population Estimate: Urban: 9,200 Rural: 239,9001 249,100 Area in Square Kilometers: 17,343 Capital: Qalat (formerly known as Qalat-i Ghilzai) Names of Districts: Arghandab, Baghar, Day Chopan, Jaldak, Kaker, Mizan, Now Bahar, Qalat, Shah Joy, Shamulza’i, Shinkay Composition of Population: Ethnic Groups: Religions: Tribal Groups: Tokhi & Hotaki Majority Pashtun Predominately Sunni Ghilzais, Noorzai &Panjpai Islam Durranis Occupation of Population Major: Agriculture (including opium), labor, Minor: Trade, manufacturing, animal husbandry smuggling Crops/Farming/ Poppy, wheat, maize, barley, almonds, Sheep, goat, cow, camel, donkey Livestock:2 grapes, apricots, potato, watermelon, cumin Language: Overwhelmingly Pashtu, although some Dari can be found, mostly as a second language Literacy Rate Total: 1% (1% male, a few younger females)3 Number of Educational Primary & Secondary: 168 (98% all Colleges/Universities: None, although Institutions: 80 male) 35272 student (99% male), some training centers do exist for 866 teachers (97% male) vocational skills Number of Security Incidents, January: 3 May: 6 September: 7 2007:774 February: 4 June: 8 October: 7 March: 3 July: 8 November: 10 April: 11 August: 5 December: 5 Poppy (Opium) Cultivation: 2006: 3,210ha 2007: 1,611ha NGOs Active in Province: Ibn Sina, Vara, ADA, Red Crescent, CADG Total PRT Projects: 40 Other Aid Projects: 573 Planned Cost: $8,283,665 Planned Cost: $19,983,250 Total Spent: $2,997,860 Total Spent: $1,880,920 Transportation: 1 Airstrip in Primary Roads: The ring road from Ghazni to Kandahar passes through Qalat and Qalat “PRT Air” – 2 flights Shah Joy. -

P4 P12community

Community Community The Qatar No German Chapter of woman has served the Institution on the International P4of Engineers (India) P12 Space Station, which orbits organises a seminar on about 400 kilometres above ‘Role of Engineers in the the earth. Two women are Development of Nation.’ hoping to change that. Wednesday, August 23, 2017 Dhul-Hijja 1, 1438 AH DOHA 34°C—42°C TODAY LIFESTYLE/HOROSCOPE 8 PUZZLES 9 & 10 Brilliant Barshim With the IAAF World Championships to his name and a stadium record COVER just a week later, Qatari high jumper STORY Mutaz Essa Barshim has been soaring high. P6-7 2 GULF TIMES Wednesday, August 23, 2017 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.51am Shorooq (sunrise) 5.11am Zuhr (noon) 11.37am Asr (afternoon) 3.06pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.04pm Isha (night) 7.34pm USEFUL NUMBERS Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 The Man with the Iron Heart soldiers, Jan Kubis and Jozef Gabcik. One is Czech, the Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 DIRECTION: Cedric Jimenez other Slovak. Both have joined forces with the Resistance Local Directory 180 CAST: Rosamund Pike, Mia Wasikowska, Jack O’Connell to free their country from the German occupation. They International Calls Enquires 150 SYNOPSIS: The dazzling ascent of Reinhard Heydrich, trained in London and volunteered to accomplish one of the Hamad International Airport 40106666 a fallen soldier, trained towards Nazi ideology by his wife most important secret missions, and one of the most risky Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Lina. Himmler’s right arm and leader of the Gestapo, also: eliminate Heydrich. -

Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and Uprightness of Rajputs

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 8 (2021)pp: 15-39 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Chronicles of Rajputana: the Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs Suman Lakhani ABSTRACT Many famous kings and emperors have ruled over Rajasthan. Rajasthan has seen the grandeur of the Rajputs, the gallantry of the Mughals, and the extravagance of Jat monarchs. None the less history of Rajasthan has been shaped and molded to fit one typical school of thought but it holds deep secrets and amazing stories of splendors of the past wrapped in various shades of mysteries stories. This paper is an attempt to try and unearth the mysteries of the land of princes. KEYWORDS: Rajput, Sesodias,Rajputana, Clans, Rana, Arabs, Akbar, Maratha Received 18 July, 2021; Revised: 01 August, 2021; Accepted 03 August, 2021 © The author(s) 2021. Published with open access at www.questjournals.org Chronicles of Rajputana: The Valour, Sacrifices and uprightness of Rajputs We are at a fork in the road in India that we have traveled for the past 150 years; and if we are to make true divination of the goal, whether on the right hand or the left, where our searching arrows are winged, nothing could be more useful to us than a close study of the character and history of those who have held supreme power over the country before us, - the waifs.(Sarkar: 1960) Only the Rajputs are discussed in this paper, which is based on Miss Gabrielle Festing's "From the Land of the Princes" and Colonel James Tod's "Annals of Rajasthan." Miss Festing's book does for Rajasthan's impassioned national traditions and dynastic records what Charles Kingsley and the Rev. -

BALUSA Track II Photo Series Acknowledgement: Most of the Following Photographs Are Courtesy of Toufiq Siddiqi, Founding Member

BALUSA Track II Photo Series Acknowledgement: Most of the following photographs are courtesy of Toufiq Siddiqi, founding member of BALUSA. BALUSA I: Bellagio, Italy- June 19-23, 1996 Satish Nambiar (back); Mahmud Durrani; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Najam Sethi; Bharat Bhushan; Supi Kaul Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Bharat Bhushan; Supi Kaul; Shaharyar Khan Mahmud Durrani; Supi Kaul Shaharyar Khan; Satish Nambiar; Bharat Bhushan; Shirin Tahir- Kheli; Mahmud Durrani; Supi Kaul; Bridget Grimes; Shekhar Gupta; Najam Sethi Mahmud Durrani; Supi Kaul; Shaharyar Khan Satish Nambiar; Najam Sethi; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Supi Kaul; Mahmud Durrani Mahmud Durrani; Shirin Tahir-Kheli BALUSA III: Princeton, New Jersey- May 2-4, 1997 Girish Saxena; Mahmud Durrani; Supi Kaul Girish Saxena, Mahmud Durrani; V. Arunachalam; Supi Kaul; Shaharyar Khan; Shirin Tahir- Kheli; Syed Babar Ali Mahmud Durrani; Girish Saxena Shaharyar Khan; Girish Saxena; Shahid Javed Burki Pratap Kaul; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Shaharyar Khan; Mahmud Durrani; Supi Kaul; V. Arunachalam (back to camera) Supi Kaul; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Pratap Kaul Mahmud Durrani; Toufiq Siddiqi; Shaharyar Khan; Supi Kaul; V. Arunachalm; Syed Babar Ali BALUSA IV: Muscat, Oman- March 20-23, 1998 Mahmud Durrani; Shahid Khaqan Abbasi; Supi Kaul; Dr. Omar Zawawi (HOST); Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Shaharyar Khan; Girish Saxena; Pratap Kaul; Shah Mahmood Qureshi; Senior Omani official; Hilal Raza Kent Biringer; Shaharyar Khan; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Shahid Khaqan Abbasi Salman Haidar; Syed Babar Ali; Shaharyar Khan Girish Saxena; Mahmud Durrani; Pratap Kaul Al Bustan Palace Hotel (Venue for BALUSA) Supi Kaul; Shah Mahmood Qureshi; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Raja Mohan Dr. Omar Zawawi; Pratap Kaul; Shirin Tahir-Kheli; Senior Omani official; Raja Mohan Dr. -

(Aamir Khan) Adalah Mantan Atlet Gulat Yang Mengingink

BAB IV DESKRIPSI OBJEK PENELITIAN 4.1. Sinopsis Film Mahavir Singh Phogat (Aamir Khan) adalah mantan atlet gulat yang menginginkan anak laki-laki untuk dapat mewujudkan impiannya menjadikan anaknya sebagai pegulat agar memperoleh medali emas untuk Negara India, tetapi istrinya Daya Shobha Kaur (Sakshi Tanwar) melahirkan empat anak perempuan, sejak itu Mahavir Singh Phogat mengubur impiannya memiliki anak laki-laki. Keajaiban muncul ketika Geeta Kumari Phogat (anak pertama) dan Babita Kumari Phogat (anak kedua) memukul anak laki-laki tetangganya hingga luka parah, hal ini membuat Mahavir Singh Phogat kembali menjadikan kedua anaknya sebagai pegulat walaupun perempuan. 76 Mahavir Singh mulai melatihan gulat secara rutin kedua anak perempuannya, Geeta Kumari Phogat dan Babita Kumari Phogat, harus bangun jam 5 pagi latihan kemudian kembali dari sekolah lanjut latihan hingga malam bahkan Ayahnya berpesan pada istrinya untuk tidak melibatkan kedua putrinya dalam membantu pekerjaan rumah karena hanya akan fokus pada latihan gulat.77 Suatu ketikan kedua anak perempuan itu merasa jenuh dengan latihan terus-menerus dan dirampas dunia masa anak-anaknya untuk bermain bersama 76https://sinopsisfilmbioskopterbaru.com/dangal-2016-sinopsis-lengkap-film-dan/ diakses pada 26 Desember 2017 pkl 18.50 WIB. 77https://sinopsisfilmbioskopterbaru.com/dangal-2016-sinopsis-lengkap-film-dan/ diakses pada 26 Desember 2017 pkl 18.50 WIB. 46 teman-teman perempuannya bahkan rambut panjangnya dipotong agar tidak mengganggu dalam latihan gulat, dengan itu mereka mencari -

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of Change?: Impact of Railways on Colonial North Indian Society, 1855-1920. Phd Thesis. SO

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of change?: impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855‐1920. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17363 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Wheels of Change? Impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855-1920. Aparajita Mukhopadhyay Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2013 Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 | P a g e Declaration for Ph.D. Thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work that I present for examination. -

Siddique Phd Complete File for CD March 2020

RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHTS OF MAULANA WAHIDUDDIN KHAN By SIDDIQUE AHMAD SHAH PhD Thesis DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR Session: 2011-2012 RELIGIO-POLITICAL THOUGHTS OF MAULANA WAHIDUDDIN KHAN A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, University of Peshawar in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By SIDDIQUE AHMAD SHAH DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR Session: 2011-2012 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis entitled “Religio-Political Thoughts of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan” submitted by Siddique Ahmad Shah in partial fulfillment of requirements for award of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History is hereby approved. __________________________ External Examiner __________________________ Supervisor Dr. Syed Waqar Ali Shah Department of History University of Peshawar _________________________ Chairman Department of History University of Peshawar DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled “Religio-Political Thoughts of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan” is the outcome of my individual research and it has not been submitted concurrently to any other university for any other degree. Siddique Ahmad Shah PhD Scholar FORWARDING SHEET The thesis entitled “Religio-Political Thoughts of Maulana Wahiduddin Khan ” submitted by Siddique Ahmad Shah , in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History has been completed under my guidance and supervision. I am satisfied with the quality of this research work. Dated: (Dr. Syed Waqar Ali Shah) (Supervisor) To My wife Table of Contents S. No Title Page No. 1. Glossary i 2. Acknowledgements vi 3. Abstract viii 4. Introduction 1-11 5. CHAPTER 1 12-36 Early Life, Education, Mission and Features of Personality 6. -

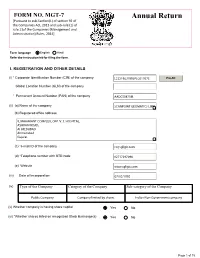

Annual Return

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company (ii) (a) Name of the company (b) Registered office address (c) *e-mail ID of the company (d) *Telephone number with STD code (e) Website (iii) Date of Incorporation (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. PRINCIPAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF THE COMPANY *Number of business activities 1 S.No Main Description of Main Activity group Business Description of Business Activity % of turnover Activity Activity of the group code Code company J J8 III. -

3Rd All India Media Educators' Conference-2018 on Power of Media and Technology: Shaping the Future

CONFERENCE REPORT 3RD ALL INDIA MEDIA EDUCATORS' CONFERENCE-2018 ON POWER OF MEDIA AND TECHNOLOGY: SHAPING THE FUTURE July 6 - 8, 2018 Geeta Girdhar Sabhagaar Pearl Academy of Fashion Designing & Media Jaipur Jointly Organised By: Centre for Mass Communication, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Department of Communication & Journalism, Gauhati University, Guwahati Lok Samvad Sansthan, Jaipur Submitted By: Kalyan Singh Kothari Secretary Lok Samvad Sansthan BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT During the last 70 years since Independence, the position of media has taken a radical shift in India. The ingrained transformation of the Indian society during its journey in the last seven decades, especially in the post-globalization period, has left a noteworthy impact on media. The evolution has also placed challenges before the Indian media scenario. The character of these challenges has kept on changing with the emergence of new social, cultural and political context and has assumed a new perspective following the advent of information technology, Internet and social media, visible in the multiplicity of platforms. The Indian media had a sound role in the struggle for Independence. But it faces a challenge in the present scenario to maintain its high standards commensurate with its glorious past. Subsequently, the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been entering into all forms of media. Though the entertainment media industry has been the prime area of FDI, the other genres like print, electronic even radio industries are now becoming lucrative targets of FDI. Though a focus is laid on the expansion of facilities or creation of new geographic market to speak high about FDI in media sector, experience and apprehensions point to several negative aspects.