KAREL HUSA New World Records 80493

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Recital the Webster Trio

) FACULTY RECITAL THE WEBSTER TRIO r1 LEONE BUYSE, flute ·~ MICHAEL WEBSTER, clarinet ROBERT MOEL/NG, piano Friday, September 19, 2003 8:00 p.m. Lillian H Duncan Recital Hall RICE UNNERSITY PROGRAM Dance Preludes Witold Lutoslawski . for clarinet and piano (1954) (1913-1994) Allegro molto ( Andantino " Allegro giocoso Andante Allegro molto Dolly, Op. 56 (1894-97) (transcribed for Gabriel Faure flute, clarinet, and piano by M. Webster) (1845-1924) Berceuse (Lullaby) Mi-a-ou Le Jardin de Dolly (Dolly's Garden) Ketty-Valse Tendresse (Tenderness) Le pas espagnol (Spanish Dance) .. Children of Light Richard Toensing ~ for flute, clarinet, and piano (2003, Premiere) (b. 1940) Dawn Processional Song ofthe Morning Stars The Robe of Light Silver Lightning, Golden Rain Phos Hilarion (Vesper Hymn) INTERMISSION Round Top Trio Anthony Brandt for flute, clarinet, and piano (2003) (b. 1961) Luminall Kurt Stallmann for solo flute (2002) (b. 1964) Eight Czech Sketches (1955) KarelHusa (transcribed for flute, clarinet, (b. 1921) and piano by M. Webster) Overture Rondeau Melancholy Song Solemn Procession Elegy Little Scherzo Evening Slovak Dance j PROGRAM NOTES Dance Preludes . Witold Lutoslawski Witold Lutoslawski was born in Warsaw in 1913 and became the Polish counterpart to Hunga,y's Bela Bart6k. Although he did not engage in the exhaustive study of his native folk song that Bart6k did, he followed Bart6k's lead in utilizing folk material in a highly individual, acerbic, yet tonal fash .. ion. The Dance Preludes, now almost fifty years old, appeared in two ver sions, one for clarinet, harp, piano, percussion, and strings, and the other for clarinet and piano. -

Tuba Syllabus / 2003 Edition

74058_TAP_SyllabusCovers_ART_Layout 1 2019-12-10 10:56 AM Page 36 Tuba SYLLABUS / 2003 EDITION SHIN SUGINO SHIN Message from the President The mission of The Royal Conservatory—to develop human potential through leadership in music and the arts—is based on the conviction that music and the arts are humanity’s greatest means to achieve personal growth and social cohesion. Since 1886 The Royal Conservatory has realized this mission by developing a structured system consisting of curriculum and assessment that fosters participation in music making and creative expression by millions of people. We believe that the curriculum at the core of our system is the finest in the world today. In order to ensure the quality, relevance, and effectiveness of our curriculum, we engage in an ongoing process of revitalization, which elicits the input of hundreds of leading teachers. The award-winning publications that support the use of the curriculum offer the widest selection of carefully selected and graded materials at all levels. Certificates and Diplomas from The Royal Conservatory of Music attained through examinations represent the gold standard in music education. The strength of the curriculum and assessment structure is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of outstanding musicians and teachers from Canada, the United States, and abroad who have been chosen for their experience, skill, and professionalism. An acclaimed adjudicator certification program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in helping all people to open critical windows for reflection, to unleash their creativity, and to make deeper connections with others. -

Wind Symphony School of Music Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-29-2012 Student Ensemble: Wind Symphony School of Music Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation School of Music, "Student Ensemble: Wind Symphony" (2012). School of Music Programs. 611. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/611 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University College of Fine Arts School of Music WIND SYMPHONY Stephen K. Steele, Conductor James F. Keene, Guest Conductor Carl Schimmel, Guest Composer Thomas Giles, Concerto Winner The Illinois State University Bands dedicate this concert and future performances to Allison Christine Zak Center for the Performing Arts Sunday Afternoon April 29, 2012 3:00 p.m. This is the two hundred and fourteenth program of the 2011-2012 Season. Program Carl Schimmel Oulipian Episodes (2012) (born 1975) I. Mots-Croisés II. "Intermezzo" from Orlando III. Malakhités IV. “Laborynthus” from Suite Sérielle 94 V. “Entr’acte” from This Golden Sickle in the Field of Stars VI. Incertum, op. 74 VII. La Toupie Premiere Performance Ingolf Dahl Concerto for Alto Saxophone (1912-1970) and Wind Orchestra (1949) I. Recitative II. Adagio (Passacaglia) III. Rondo alla marcia: Allegro Thomas Giles, Concerto Competition Winner Intermission Award Ceremony Percy Grainger Lincolnshire Posy (1937) (1882-1961) I. -

School of Music

School of Music WIND ENSEMBLE AND CONCERT BAND Gerard Morris and Judson Scott, conductors WEDNESDAY, APRIL 12, 2017 | SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL | 7:30 P.M. PROGRAM Concert Band Judson Scott, conductor Rhythm Stand ....................................Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962) For Angels, Slow Ascending ......................... Greg Simon ’07 (b. 1985) The Green Hill ....................................Bert Appermont (b. 1973) Zane Kistner ‘17, euphonium Melodious Thunk ..............................David Biedenbender (b. 1984) INTERMISSION Wind Ensemble Gerard Morris, conductor Forever Summer (Premiere) ...................... Michael Markowski (b. 1986) Variations on Mein junges Leben hat ein End ................Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Ricker, trans. Music for Prague 1968 .............................. Karel Husa (1921–2016) I. Introduction and Fanfare II. Aria III. Interlude IV. Toccata and Chorale PROGRAM NOTES Concert Band notes complied by Judson Scott Wind Ensemble notes compiled by Gerard Morris Rhythm Stand (2004) ........................................... Higdon Rhythm Stand by Jennifer Higdon pays tribute to the constant presence of rhythm in our lives from the pulse of the world around us, celebrating the “regular order” we all experience, and incorporating traditional and nontraditional sounds within a 4/4-meter American-style swing. In the composer’s own words: “Since rhythm is everywhere, not just in music (ever listen to the lines of a car running across pavement, or a train on a railroad track?), I’ve incorporated sounds that come not from the instruments that you might find in a band, but from objects that sit nearby—music stands and pencils!” For Angels, Slow Ascending (2014) ................................. Simon The composer describes his inspiration and intention for the piece: In December 2013, we watched in silence and shock as a massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., claimed the lives of 27 people, including 20 young children. -

Evidence from Covid-19 Pandemic

RISK PERCEPTIONS AND PROTECTIVE BEHAVIORS: EVIDENCE FROM COVID-19 PANDEMIC Maria Polyakova M. Kate Bundorf Duke University Stanford University & NBER & NBER Jill DeMatteis Jialu L. Streeter Westat Stanford University Grant Miller Jonathan Wivagg Stanford University Westat & NBER April, 2021 Working Paper No. 21-022 Risk Perceptions and Protective Behaviors: Evidence from COVID-19 Pandemic.∗ M. Kate Bundorf Jill DeMatteis Grant Miller Maria Polyakova Duke University Westat Stanford University Stanford University and NBER and NBER and NBER Jialu L. Streeter Jonathan Wivagg Stanford University Westat April 28, 2021 Abstract We analyze data from a survey we administered during the COVID-19 pandemic to investigate the relationship between people's subjective risk beliefs and their protective behaviors. We report three main findings. First, on average, people substantially overestimate the absolute level of risk associated with economic activity, but have correct signals about their relative risk. Second, people who believe that they face a higher risk of infection are more likely to report avoiding economic activities. Third, government mandates restricting economic behavior attenuate the relationship between subjective risk beliefs and protective behaviors. ∗Corresponding author: Maria Polyakova ([email protected]). We are grateful to Sarah B¨ogland Aava Farhadi for excellent research assistance. We have made the de-identified survey dataset used in this manuscript available at the following link. We gratefully acknowledge in-kind survey support from Westat. 1 1 Introduction Subjective perceptions of risk guide decision making in nearly all economic domains (Hurd, 2009). While a rich theoretical literature highlights the importance of subjective beliefs for individual ac- tions, fewer studies provide empirical evidence of the link between risk perceptions and behaviors, particularly in non-laboratory settings and in high-income countries (Peltzman, 1975; Delavande, 2014; Delavande and Kohler, 2015; Mueller et al., 2021). -

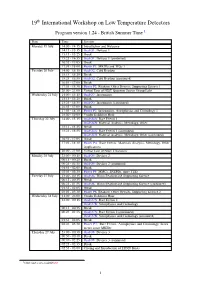

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - British Summer Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 14:00 - 14:15 Introduction and Welcome 14:15 - 15:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O3: Instruments 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 18:00 - 19:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Monday 26 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 01:55 - 02:05 Break 02:05 - 03:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Tuesday 27 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science -

The Saxophone Symposium: an Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014 Ashley Kelly Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Ashley, "The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2819. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2819 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SAXOPHONE SYMPOSIUM: AN INDEX OF THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN SAXOPHONE ALLIANCE, 1976-2014 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and AgrIcultural and MechanIcal College in partIal fulfIllment of the requIrements for the degree of Doctor of MusIcal Arts in The College of MusIc and DramatIc Arts by Ashley DenIse Kelly B.M., UniversIty of Montevallo, 2008 M.M., UniversIty of New Mexico, 2011 August 2015 To my sIster, AprIl. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sIncerest thanks go to my committee members for theIr encouragement and support throughout the course of my research. Dr. GrIffIn Campbell, Dr. Blake Howe, Professor Deborah Chodacki and Dr. Michelynn McKnight, your tIme and efforts have been invaluable to my success. The completIon of thIs project could not have come to pass had It not been for the assIstance of my peers here at LouIsIana State UnIversIty. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Adolf Busch and the Saxophone: A Historical Perspective on his Quintet, op. 34 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6cz1t09s Author Veirs, Russell Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Adolf Busch and the Saxophone: A Historical Perspective on his Quintet, op. 34 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts By Russell Dewain Veirs 2013 © Copyright by Russell Dewain Veirs 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Adolf Busch and the Saxophone: A Historical Perspective on his Quintet, op. 34 by Russell Dewain Veirs Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Gary Gray, Co-Chair Professor Douglas Masek, Co-Chair Adolf Busch, well-known as a violinist, contributed a major work to the saxophone‟s chamber repertoire in 1925 while living in Germany. This piece, Quintet, op. 34 for alto saxophone, two violins, viola, and cello, lay hidden until many decades later when it resurfaced for performance in the United States. Busch‟s use of the saxophone was advanced for the time, and his inclusion of the instrument in a quintet with strings was unique. Scattered information regarding the genesis of the piece, its advanced use of the saxophone at the time, and the discrepancies between the published score and parts all called for exploration. This study investigates the sparse history of the piece, using numerous primary and secondary sources, and offers performance suggestions so that today‟s saxophonist can deliver a performance reflecting the musical life surrounding the instrument at time of its composition. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015. -

Estimating the Overdispersion in COVID

Wellcome Open Research 2020, 5:67 Last updated: 13 JUL 2020 RESEARCH ARTICLE Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China [version 3; peer review: 2 approved] Akira Endo 1,2, Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group, Sam Abbott 1,3, Adam J. Kucharski1,3, Sebastian Funk 1,3 1Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, WC1E 7HT, UK 2The Alan Turing Institute, London, NW1 2DB, UK 3Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, London, WC1E 7HT, UK First published: 09 Apr 2020, 5:67 Open Peer Review v3 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.1 Second version: 03 Jul 2020, 5:67 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.2 Reviewer Status Latest published: 10 Jul 2020, 5:67 https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.3 Invited Reviewers 1 2 Abstract Background: A novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak has now version 3 spread to a number of countries worldwide. While sustained transmission (revision) report chains of human-to-human transmission suggest high basic reproduction 10 Jul 2020 number R0, variation in the number of secondary transmissions (often characterised by so-called superspreading events) may be large as some countries have observed fewer local transmissions than others. version 2 Methods: We quantified individual-level variation in COVID-19 (revision) report report transmission by applying a mathematical model to observed outbreak sizes 03 Jul 2020 in affected countries. We extracted the number of imported and local cases in the affected countries from the World Health Organization situation report and applied a branching process model where the number of secondary version 1 transmissions was assumed to follow a negative-binomial distribution. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1991, Tanglewood

/JQL-EWOOD . , . ., An Enduring Tradition ofExcellence In science as in the lively arts, fine performance is crafted with aptitude attitude and application Qualities that remain timeless . As a worldwide technology leader, GE Plastics remains committed to better the best in engineering polymers silicones, superabrasives and circuit board substrates It's a quality commitment our people share Everyone. Every day. Everywhere, GE Plastics .-: : ;: ; \V:. :\-/V.' .;p:i-f bhubuhh Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Grant Llewellyn and Robert Spano, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Tenth Season, 1990-91 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman Emeritus J. P. Barger, Chairman George H. Kidder, President T Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney, Vice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, V ice-Chairman Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer David B. Arnold, Jr. Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. August R. Meyer Peter A. Brooke Mrs. R. Douglas Hall III Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Francis W. Hatch Peter C. Read John F. Cogan, Jr. Julian T. Houston Richard A. Smith Julian Cohen Mrs. BelaT. Kalman Ray Stata William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. George I. Kaplan William F. Thompson Mrs. Michael H. Davis Harvey Chet Krentzman Nicholas T. Zervas Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett R. Willis Leith, Jr. Trustees Emeriti Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Mrs. George R. Rowland Philip K. Allen Mrs. John L. Grandin Mrs. George Lee Sargent Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Sidney Stoneman Leo L. Beranek Albert L. Nickerson John Hoyt Stookey Mrs. John M. Bradley Thomas D. Perry, Jr. -

MMTA Winter 2004 Newsletter

MISSISSIPPI MUSIC TEACHER The official publication of the Mississippi Music Teachers Association An affiliate of Music Teachers National Association Volume 20, Issue 1 Winter, 2004 I N T H I S I S S U E @ President’s Message @ Board Reports @ Affiliate Reports @ 2003 Convention Results @ Convention Scrapbook @ News from MTNA @ Upcoming Events @ 2004 Membership Directory @ Certification News @ Our 30-Year Honoree @ MTNA Convention Information Janet Gray, Jacquelyn Thornell and Barbara Tracy enjoy posing at the 2003 Convention. I’d buy cookies from these ladies! Another admiring student in The talented studio of Jan Mesrobian. Erin Dyer with Stacy Rodgers Graham Purkerson’s studio. Great Certification News! Calling all uncertified MMTA members!!! On January 10, 2004, the MMTA Board voted to set aside $1400 to reimburse the first 10 newly certified teachers in the next two years. This is how the program will work: 1. Decide to get your certification 2. Do it before January 10, 2006 3. Submit documentation to the MMTA Executive Committee that you paid the $140 in fees If you are among the first 10 MMTA members to apply for this program, you will be reimbursed for your certification fees. Thanks to Sharon Lebsack who became aware of this program in the Arizona MTA and shared this great idea with our board! MMT Newsletter 1 President’s Message Happy New Year, and welcome to the 50th year of the Mississippi Music Teachers Association! Plans are in the making for a festive convention worthy of this milestone, and I want you to think now about your role in the proceedings.