31295000314483.Pdf (7.202Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recreation and Parks at Texas A&M

R E C R E A T I O N A N D P A R K S AT T E X A S A & M College Station, Texas No. 7, December, 1966 Faculty: Carroll Dowell Since the weeks have slipped by so David Reed rapidly since our last newsletter, Ivan Schmedemann this is the time to say: Frank Suggitt L.M. Reid “MERRY CHRISTMAS AND THE HAPPIEST OF NEW YEARS!” Secretaries: Marilyn Andrews (from the folks to the left) Pam Boyd Diann Weaver Since so much has happened, this issue had best be limited to brief notice of many items of interest. CONFERENCES. Since September the Recreation and Parks faculty participated in the: * National Recreation and Park Congress – Washington, D.C. * Soil Conservation Service Recreation Training Conference – Temple, Texas * Texas Recreation and Park Society Annual Conference – Abilene, Texas * Texas Social Welfare Association Annual Conference – Fort Worth, Texas * Louisiana Recreation and Park Association Annual Conference – Alexandria, Louisiana * 11th Annual Water for Texas Conference – Texas A&M * 21st Texas Turfgrass Conference – Texas A&M * State University and Land—Grant College Annual Conference – Washington, D.C. * Society of American Foresters Chapter meeting – Huntsville, Texas * Vocational Agriculture Recreation Training Conference – Waco, Texas * Texas Agricultural Experiment Station Annual Conference – Texas A&M FOOTBALL. After a poor start, our Aggies put together a winning streak that had them tied, for three weeks, for first place in the Southwest Conference. Then came a late season fizzle, and a final 4—5—1 record. ‘Nuff said. -2- DEPARTMENT OFFICES. The move reported in the September Newsletter has long since been more or less complete. -

Stephenville Curriculum Document Social Studies Grade: 7 Course: Texas History Bundle (Unit) 5 Est

STEPHENVILLE CURRICULUM DOCUMENT SOCIAL STUDIES GRADE: 7 COURSE: TEXAS HISTORY BUNDLE (UNIT) 5 EST. NUMBER OF DAYS: 20 UNIT 5 NAME REVOLUTION AND REPUBLIC With tensions increasing between the Mexican government and American settlers in Texas, diplomacy gave way to Unit Overview Narrative inevitable conflict that erupted into war. Emerging victorious, Texas separated itself from Mexico and became its own Republic. Generalizations/Enduring Understandings Concepts Guiding/Essential Questions Learning Targets Formative Assessments Summative Assessments TEKS Specifications (1) History. The student understands traditional historical points of reference in Texas history. The Texans earned their independence from Mexico student is expected to: (A) identify the major eras in Texas history, Events: describe their defining characteristics, and Battle of Gonzales explain why historians divide the past into eras, Alamo TEKS (Grade Level) / Specifications including Natural Texas and its People; Age of Goliad Massacre Contact; Spanish Colonial; Mexican National; Battle of San Jacinto Revolution and Republic; Early Statehood; Texas Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo in the Civil War and Reconstruction; Cotton, Cattle, and Railroads; Age of Oil; Texas in the People: Great Depression and World War II; Civil Rights Sam Houston and Conservatism; and Contemporary Texas; William B. Travis (B) apply absolute and relative chronology James Fannin through the sequencing of significant Antonio López de Santa Anna individuals, events, and time periods; Juan N. Seguín (C) explain the significance of the following 1836- Texans earned their independence from Mexico dates: 1519, mapping of the Texas coast and through a series of events including the siege of the Alamo, first mainland Spanish settlement; 1718, the massacre at Goliad, and the battle of San Jacinto. -

STAAR Alternate 2 Prerequisite Skill Guide

STAAR Alternate 2 Prerequisite Skill Guide Subject: US History Grade: ____ Student: _________________________ Essence Statement RC1: Recognizes the impact of U.S. participation in World war II. (7) STAAR Reporting Category 1– History/TEKS: 7 The student understands the domestic and international impact of U.S. participation in World War II. Directions: Begin at the bottom of each focus area and check off the prerequisite skills the student has mastered. Begin instruction at the next highest prerequisite skill not yet mastered. Work on skills in each focus area (as appropriate) in order to instruct the depth and breadth of the Curriculum Framework. (Note: Essence statements may have more than one focus.) Focus: Events Prior and During Military and Diplomatic Conflicts Date: More Grade Prerequisite Skills: Mastered/M Complex Target/T explain the causes of the Civil War, including sectionalism, states' rights, and slavery, and significant events of the Civil War, including the firing on Fort Sumter; the battles of Antietam, 8 Gettysburg, and Vicksburg; the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation; Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House; and the assassination of Abraham Lincoln explain reasons for the involvement of Texas in the Civil War such 7 as states' rights, slavery, sectionalism, and tariffs trace the development of events that led to the Texas Revolution, including the Fredonian Rebellion, the Mier y Terán Report, the 7 Law of April 6, 1830, the Turtle Bayou Resolutions, and the arrest of Stephen F. Austin identify and analyze -

Arter: No Aid to Help Ducate Illegal Aliens

The Weather Yesterday Today ir facility yoy. f services y e-ups to coi/ WE areope! he attalion High................... ..........................96 High................................ .............97 T B Low...................... .......................... Low................................... .............73 Serving the Texas A&M University community 73 Humidity. ...................61% Humidity................... ..67% Vol. 74 No. 12 Tuesday, September 16, 1980 USPS 045 360 Rain................... Chance of rain . slight doon’ 14 Pages College Station, Texas Phone 845-2611 n: Tues.-Satl Sundays 8-11 693-8682 OFF arter: No aid to help Ross Volunteers m escort Clements 'earn Cone The Ross Volunteers, an honorary com the largest parade at the Mardi Gras Parade ise of sub pany of the Texas A&M University Corps of in New Orleans. Cadets, tonight will serve as the official upon) ducate illegal aliens The 72 members of the Ross Volunteers honor guard at a Reagan-Bush fund-raising were selected in the fall of their junior year of Blue Belt ceremony in Houston. based upon several factors, including their 'ream United Press International Carter said federal impact aid is designed al impact act to school districts harmed by during the hour-long meeting, and drew The company, the governor’s official character traits, academic and military CORPUS CHRISTI —Texas is not likely to assist school districts adversely impacted the court decision. warm applause for his commitment to honor guard, was invited by Gov. Bill Cle standing, social graces and disciplinary re ) avoid a court order to educate the chil- by activities of the federal government, and Carter, campaigning for the Hispanic maintain the Corpus Christi Naval Air Sta ments to the function. -

Chapter 9 Quiz

Name: ___________________________________ Date: ______________ 1. The diffusion of authority and power throughout several entities in the executive branch and the bureaucracy is called A) the split executive B) the bureaucratic institution C) the plural executive D) platform diffusion 2. A government organization that implements laws and provides services to individuals is the A) executive branch B) legislative branch C) judicial branch D) bureaucracy 3. What is the ratio of bureaucrats to Texans? A) 1 bureaucrat for every 1,500 Texas residents B) 1 bureaucrat for every 3,500 Texas residents C) 1 bureaucrat for every 4,000 Texas residents D) 1 bureaucrat for every 10,000 Texas residents 4. The execution by the bureaucracy of laws and decisions made by the legislative, executive, or judicial branch, is referred to as A) implementation B) diffusion C) execution of law D) rules 5. How does the size of the Texas bureaucracy compare to other states? A) smaller than most other states B) larger than most other states C) about the same D) Texas does not have a bureaucracy 6. Standards that are established for the function and management of industry, business, individuals, and other parts of government, are called A) regulations B) licensing C) business laws D) bureaucratic law 7. What is the authorization process that gives a company, an individual, or an organization permission to carry out a specific task? A) regulations B) licensing C) business laws D) bureaucratic law 8. The carrying out of rules by an agency or commission within the bureaucracy, is called A) implementation B) rule-making C) licensing D) enforcement 9. -

Chapter 3 Assessment.Pdf

068 11/15/02 5:05 PM Page 68 TERMS & NAMES READING SOCIAL STUDIES Explain the significance of each of the After You Read following: Review your completed chart. Using 1. Rio Grande the information in each column, Mapping Texas Lands 2. Coastal Plains region write your own definitions for Texas can be divided into 3. North Central Plains region physical geography and human regions of similar landforms, geography. Then, with a partner, 4. Great Plains region climate, and precipitation. discuss the following questions: 5. Mountains and Basins region Which key words reflect the physi- 6. census cal geography and human geogra- phy of your town or city? How has REVIEW QUESTIONS the physical geography had an Mapping Texas Lands (pages 46–50) impact on the human geography? 1. Which is likely to change more GEOGRAPHY over a ten-year period, an area’s physical geography or Physical Human Geography Geography its human geography? Explain. 2. Why do you think average temperatures decrease as Mapping Texas People elevation increases? People are drawn to some Identifying the Four Regions of regions more than others Texas (pages 52–57) because of climate, natural resources, 3. Rank the four regions of Texas or the availability in order from largest to small- of jobs. est. How might life in Texas differ if this order were reversed? 4. Based on your knowledge of CRITICAL THINKING Texas regions, what type of Drawing Conclusions physical geography would you expect to see in northern 1. What do you think is the value Mexico? in eastern New of understanding the physical Mexico? in southern Okla- geography of Texas? Identifying the Four homa? in western Louisiana? Drawing Conclusions Regions of Texas Mapping Texas People (pages 61–67) 2. -

The Methodist Book Concern in the West

This building as represented above, located at No. 420 Plum Street, Cincinnati, Ohio, was erected in 1916. It is 114 feet on Plum Street, extending east 189 feet to Home Street, and 124 feet on Home Street, and contains approximately 112,000 square feet of floor space. The entire building is occupied by the Book Concern and other Methodist activities. One Hundred Years of Progress An Account of the Ceremonies held at Cincinnati, Ohio, Wednesday, October Sixth, Nineteen Hundred and Twenty, commemora ting the establishment of The Methodist Book Concern in the West Edited by CHARLES W. BARNES, D.D. THE METHODIST BOOK CONCERN CINCINNATI, OHIO Contents PAGE THE INVITATION 7 I PROGRAM - 9 II THE HOUSE OF GOOD BOOKS ::; 17 III THE STORY OF THE OCCASION 20 IV THE PROGRAM As RENDERED 30 V SKETCHES OF THE WESTERN PUBLISHING AGENTS 87 VI THE WELFARE WORK AND SOCIAL ACTIVITIES 98 VII THE METHODIST BOOK CONCERN FAMILY 105 October 6th October 6th 1820 1920 ,~HE Publishing Agents and the Book '-' Committee of the Methodist Epis copal Church cordially invite you to be pres en t at the exercises commemorating the cen tennial of the establishment of The Meth odist Book Concern in the West, to be held at Cincinnati, Ohio, Wednesday, October the sixth, One thousand nine hundred and twenty- -; A luncheon will be served on Wednesday during the noon hour in the coun ting room. At four o'clock Wednesday afternoon each of the sites occupied by The Methodist Book Concern during the century will be visi ted in order. -

Howard Payne University Football Records (Last Updated 11/3/18)

Howard Payne University Football Records (last updated 11/3/18) INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Rushing Most Att. -Season 246 Richard Green, 1999 Most Att.-Game 43 Charles Bennett vs. ASU, 1984 Most Att. –Career 755 Willie Phea, 1974 – 1977 Most Yds. –Season 1,307 Richard Green, 1999 Most Yds. –Game 306 Cliff Hall, 1994 Most Yds. –Career 3,621 Richard Green, 1997- 2002 Passing Most Att. –Season 450 Zach Hubbard, 2009 Most Att. –Game 63 Zach Hubbard vs. Louisiana College, 2009 Most Att. – Career 1,164 Scott Lichner, 1991 – 1994 Most Comp. –Season 264 Zach Hubbard, 2009 Most Comp –Game 39 Gage McClanahan vs Southwestern, 2018 38 Adam King vs. HSU, 2004 38 Zach Hubbard vs Louisiana College, 2009 Most Comp –Career 653 Scott Lincher, 1991- 1994 Most Yds. –Season 3,584 Scott Lincher, 1992 Most Yds –Game 532 Zach Hubbard vs.Louisiana College, 2009 Most Yds –Career 10,246 Adam King, 2001- 2004 Most TD Passes –Season 33 Scott Lincher, 1991 Most TD Passes –Game 6 Adam King vs. ETBU, 2001 Most TD Passes –Career 84 Scott Lincher, 1991 – 1994 Most INT’s Thrown –Season 21 Rick Worley, 1974 Most INT’s Thrown –Game 8 Craig Smith vs. ASU, 1977 Most INT’s thrown –Career 58 Jerrod Summers, 1986 – 1989 Best Comp. Perc. –Season 64.8% Adam King, 2002 Best Comp. Perc. –Game (min 20 attempts) 86.3% Thomas Head vs Wayland, 2012 - 19 of 22 86.2% Adam King vs. Mississippi College, 2003 - 25of 29 Receiving Most Rec. –Season 99 Kevin Hill, 1992 Most Rec. –Game 15 Keith Crawford vs. -

Trammel's Trace on Printed Maps of the 19Th Century

CRHR Research Reports Volume 1 Article 2 2-18-2015 Trammel's Trace on Printed Maps of the 19th Century Kelley A. Snowden Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/crhr_research_reports Part of the Geography Commons, and the History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Snowden, Kelley A. (2015) "Trammel's Trace on Printed Maps of the 19th Century," CRHR Research Reports: Vol. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/crhr_research_reports/vol1/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in CRHR Research Reports by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trammel’s Trace on Printed Maps of the 19th Century Kelley A. Snowden Center for Regional Heritage Research, Stephen F. Austin State University ____________________________________________________________________________________ Trammel’s Trace was a nineteenth century road that traversed East Texas. Recognized today as a historic cartographic feature, this road appeared in different ways on nineteenth century printed published maps over time, and in the mid-to-late nineteenth centu- ry was reduced from a route to a fragment. This study is the first to examine the portrayal of the Trace as a historic cartographic feature, how it was presented to the general public, how its portrayal changed over time, and why it appears on the maps at all. In addition, this study is the first to use geographic information systems (GIS) to analyze the presentation of the Trace on printed, published maps. -

Veterans Day Ceremony

VETERANS DAY CEREMONY Friday, Nov. 11, 2016 • 5 p.m. Louis L. Adam Memorial Plaza, Veterans Park & Athletic Complex 3101 Harvey Road • College Station, Texas 2016 Board of Directors and Officers Memorial for all Veterans of the Brazos Valley, Inc. John Anderson . .Audit Committee Steve Beachy . Special Assistant to the President Glenn Burnside . .Chaplain Irma Cauley . Brazos County Representative Chip Dawson . History Committee (Chair) Chris Dyer . ACBV Ex-Officio Representative Jerry Fox . Treasurer Dennis Goehring . .Fundraising Committee Mike Guidry . .Event Committee John Happ . .Vice President, Development Committee (Chair) Brian Hilton . Secretary Randy House . President Fain McDougal . Development Committee Mike Neu . Chief Information Officer Committee (Chair) Louis Newman . Development Committee David Sahm . .Design Committee (Vice Chair) David Schmitz . .City of College Station Representative Jim Singleton . .Design Committee (Chair) Travis Small . Special Assistant to the President Kean Register . City of Bryan Representative Perry Stephney . Event Committee John Velasquez . Flag Coordinator Bill Youngkin . Event Committee (Chair) Veteran Affiliations Air Force Association National Sojourners American Legion Order of Daedalians Brazos Valley Marine Corps League Veterans of Foreign Wars Disabled American Veterans Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association Military Officers Assoc. of America Vietnam Veterans of America 2 Veterans Day Program 11 November 2016 5 p.m. Brazos Valley Veterans Memorial Veterans Park & Athletic Complex College Station, Texas Honor Wall Roll Call Bill Youngkin, Esq. BVVM Board of Directors Welcome Remarks LTG Randolph House, USA (Ret.) President, BVVM Board of Directors Invocation MAJ Glenn Burnside, USMC (Ret.) Chaplain, BVVM Board of Directors National Anthem, Texas Our Texas The Fightin’ Texas Aggie Band Special Recognition of LTG Randolph House, USA (Ret.) Community Partners Special Recognition of Bill Youngkin, Esq. -

Convention Grade 7

Texas Historical Commission Washington-on-the-Brazos A Texas Convention Grade 7 Virtual Field Trip visitwashingtononthebrazos.com Learning Guide Grade 7 Childhood in the Republic Overview: A New Beginning for Texas Texas became Mexican territory in 1821 and the new settlers brought by Stephen F. Austin and others were considered Mexican citizens. The distance between the settlements and Mexico (proper), plus the increasing number of settlers moving into the territory caused tension. The settlers had little influence in their government and limited exposure to Mexican culture. By the time of the Convention of 1836, fighting had already Image “Reading of the Texas Declaration of broken out in some areas. The causes of some of this Independence,” Courtesy of Artie Fultz Davis Estate; Artist: Charles and Fanny Norman, June 1936 fighting were listed as grievances in the Texas Declaration of Independence. Objectives • Identify the key grievances given by the people of Texas that lead to the formation of government in the independent Republic of Texas • How do they compare to the grievances of the American Revolution? • How do they relate to the Mexican complaints against Texas? • How did these grievances lead to the formation of government in the Republic? • Identify the key persons at the Convention of 1836 Social Studies TEKS 4th Grade: 4.3A, 4.13A 7th Grade: 7.1 B, 7.2 D, 7.3C Resources • Activity 1: 59 for Freedom activity resources • Activity 2: Declaration and Constitution Causes and Effects activity resources • Extension Activity: Order -

Summary of Understanding the Need for Adult Education

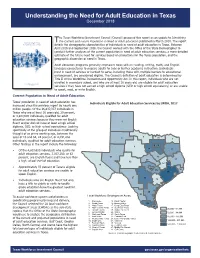

Understanding the Need for Adult Education in Texas December 2018 he Texas Workforce Investment Council (Council) prepared this report as an update to Identifying the Current and Future Population in Need of Adult Education published in March 2010. The report Understanding the Need T for Adult Education in Texas details the demographic characteristics of individuals in need of adult education in Texas. Between April 2018 and September 2018, the Council worked with the Office of the State Demographer to conduct further analyses of the current population in need of adult education services, a more detailed estimate of the future need for services based on projections for the Texas population, and the geographic dispersion of need in Texas. Adult education programs generally emphasize basic skills in reading, writing, math, and English language competency to prepare adults for jobs or further academic instruction. Individuals most in need of services or hardest to serve, including those with multiple barriers to educational enhancement, are considered eligible. The Council’s definition of adult education is determined by Title II of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. In this report, individuals who are not Texas Workforce Investment Council enrolled in secondary school, and who are at least 16 years old, are eligible for adult education December 2018 services if they have not earned a high school diploma (GED or high school equivalency) or are unable to speak, read, or write English. Current Population in Need of Adult Education Individual Eligible for Adult Eduction Service b LWDA, 2017 Texas’ population in need of adult education has Individuals Eligible for Adult Education Services by LWDA, 2017 increased since the previous report by nearly one million people.