Japan's Use of Flour Began with Noodles, Part 3 by Hiroshi Ito

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speech by Ōno Genmyō, Head Priest of the Horyu-Ji Temple “Shōtoku Taishi and Horyu-Ji” (October 20, 2018, Shinjuku-Ku, Tokyo)

Speech by Ōno Genmyō, Head Priest of the Horyu-ji Temple “Shōtoku Taishi and Horyu-ji” (October 20, 2018, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo) MC Ladies and gentlemen, thank you for coming today. The town of Ikaruga, where the Horyu-ji Temple is located, is very conveniently located: just 10 minutes by JR from Nara, 20 minutes from Tennoji in Osaka, and 80 minutes from Kyoto. This historical area is home to sites that include the Horyu-ji , the Horin-ji, the Hkki-ji, the Chugu- ji, and the Fujinoki Kofun tumulus. The Reverend Mr. Ōno will be speaking with us today in detail about the Horyu-ji, which was founded in 607 by Shotoku Taishi, Prince Shotoku, a member of the imperial family. As it is home to the oldest wooden building in the world, it was the first site in Japan to be registered as a World Heritage property. However, its attractions go beyond the buildings. While Kyoto temples are famous for their gardens, Nara’s attractions are, more than anything, its Buddhist sculptures. The Horyu-ji is home to some of Japan’s most noted Buddhist statues, including the Shaka Sanzon [Shaka Triad of Buddha and Two Bosatsu], the Kudara Kannon, Yakushi Nyorai, and Kuse Kannon. Prince Shotoku was featured on the 10,000 yen bill until 1986, so there may even be people overseas who know of him. Shotoku was the creator of Japan’s first laws and bureaucratic system, a proponent of relations with China, and incorporated Buddhism into politics. Reverend Ōno, if you would be so kind. -

Real-Life Kantei-Of Swords , Part 10: a Real Challenge : Kantei Wakimono Swords

Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho 1) Introduction Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others. Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school. Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. There is also a theory that the school was founded around the Oei era as two branches, one following a smith named Fuji from the Kyushu area and other following a smith named Yasuyoshi from the Kyoto area (who is also said to be the son of Taro Ujiyoshi). -

REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Fall 2019 CRN16061/2 Mark Unno

REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Fall 2019 CRN16061/2 Mark Unno Instructor: Mark T. Unno, Office: SCH 334 TEL 6-4973, munno (at) uoregon.edu http://pages.uoregon.edu/munno/ Wed. 2:00 p.m. - 4:50 p.m., Condon 330; Office Hours: Mon 10:00-10:45 a.m.; Tues 1:00-1:45 p.m. No Canvas site. Overview REL 444/544 Medieval Japanese Buddhism focuses on selected strains of Japanese Buddhism during the medieval period, especially the Kamakura (1185-1333), but also traces influences on later developments including the modern period. The course weaves together the examination of religious thought and cultural developments in historical context. We begin with an overview of key Buddhist concepts for those without prior exposure and go onto examine the formative matrix of early Japanese religion. Once some of the outlines of the intellectual and cultural framework of medieval Japanese Buddhism have been brought into relief, we will proceed to examine in depth examples of significant medieval developments. In particular, we will delve into the work of three contemporary figures: Eihei Dōgen (1200-1253), Zen master and founding figure of the Sōtō sect; Myōe of the Shingon and Kegon sects, focusing on his Shingon practices; and Shinran, founding figure of Jōdo Shinshū, the largest Pure Land sect, more simply known as Shin Buddhism. We conclude with the study of some modern examples that nonetheless are grounded in classical and medieval sources, thus revealing the ongoing influence and transformations of medieval Japanese Buddhism. Themes of the course include: Buddhism as state religion; the relation between institutional practices and individual religious cultivation; ritual practices and transgression; gender roles and relations; relations between ordained and lay; religious authority and enlightenment; and two-fold truth and religious practice. -

The Shôkyû Version of the Kitano Tenjin Engi Emaki: a Brief Introduction to Its Content and Function

Eras Edition 11, November 2009 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/publications/eras The Shôkyû version of the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki: A brief introduction to its content and function Sara L. Sumpter (University of Pittsburgh) Abstract: This article examines the political and social atmosphere surrounding the production of the thirteenth-century hand scroll Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Shrine), which depicts the life, death and posthumous revenge of the ninth-century courtier Sugawara no Michizane. The article combines an analysis of the content and religious iconography of the scroll, a study of early Japanese beliefs in angry spirits of the dead, and a narration of the actual life of Michizane in an attempt to produce a sketch of the rituals and superstitions of Heian and early Kamakura period Japanese society, and to suggest possible functions of the hand scroll that complement them. The hand scroll sets collectively known as the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (Illustrated Legends of the Kitano Shrine) each tell the story of the life and death of the ninth- century courtier and poet, Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), and of the posthumous revenge undertaken by his vengeful spirit (onryô). According to the scrolls, Michizane was falsely accused of treason by rivals at the Heian court who were jealous of his astronomical rise to power. He was exiled to Dazaifu on the island of Kyushu in 901 and died there two years later in despair. His spirit persisted in seeking retribution against his enemies and in reclaiming his position and honours. He is said to have stalked his numerous rivals in the form of the thunder god (raijin) before ultimately revealing to a frightened court, through a series of intermediaries, the means of his pacification: deification and worship at the Kitano Shrine in Kyoto.1 Today the Kitano Tenjin engi emaki (hereafter referred to as the Tenjin scrolls) number more than thirty extant examples, ranging in date from the early thirteenth century to the nineteenth century. -

The Establishment of State Buddhism in Japan

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository The Establishment of State Buddhism in Japan Tamura, Encho https://doi.org/10.15017/2244129 出版情報:史淵. 100, pp.1-29, 1968-03-01. Faculty of Literature, Kyushu University バージョン: 権利関係: - 1 - THE ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Encho Tamura In ancient times, during the Yamato period, it was the custom for each succeeding emperor at the beginning of his reign to seek some site on which to build a new imperial palace and relocate himself. In other words, successive emperors neither inherited their palaces from the previous emperor nor handed them down to the following emperor. Hardly any example is to be found of the same palace being used by more than two emperors successively. The fact that the emperor in ancient times was called by the name of the place where his palace was located* is based on this custom of seeking new sites and founding new palaces. < 1 > This custom was strictly adhered to until the 40th Emperor, Temmu (672-686 A. D.).** The palaces, though at times relocated at Naniwa (the present Osaka Prefecture), or at Cmi (Shiga Prefecture), in most cases were built in different locations within the boundary of the Yamato area (Nara Prefecture). It is true that there is a theory denying the existence of emperors previous to the 14th Emperor, Chuai, but it is clearly stated in both the Kojiki and the Nihonshoki that all of the emperors including Jimmu, the 1st Emperor, strictly adhered to this custom of relocating the palace. This reflects the fact *For example, Emperor Kimmei was called "Shikishima no Kanazashi no Miya ni Arne ga shita Shiroshimesu Sumeramikoto" (The Emperor who rules the whole area under heaven at his Kanazashi Palace in Shikishima). -

Real-Life Kantei of Swords Part 10

Japanese Swords Society of the United States - Volume 48 No. 4 _______________________________________________________________________________ Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho 1) Introduction Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others. Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school. Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. -

Noh Theater and Religion in Medieval Japan

Copyright 2016 Dunja Jelesijevic RITUALS OF THE ENCHANTED WORLD: NOH THEATER AND RELIGION IN MEDIEVAL JAPAN BY DUNJA JELESIJEVIC DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in East Asian Languages and Cultures in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Elizabeth Oyler, Chair Associate Professor Brian Ruppert, Director of Research Associate Professor Alexander Mayer Professor Emeritus Ronald Toby Abstract This study explores of the religious underpinnings of medieval Noh theater and its operating as a form of ritual. As a multifaceted performance art and genre of literature, Noh is understood as having rich and diverse religious influences, but is often studied as a predominantly artistic and literary form that moved away from its religious/ritual origin. This study aims to recapture some of the Noh’s religious aura and reclaim its religious efficacy, by exploring the ways in which the art and performance of Noh contributed to broader religious contexts of medieval Japan. Chapter One, the Introduction, provides the background necessary to establish the context for analyzing a selection of Noh plays which serve as case studies of Noh’s religious and ritual functioning. Historical and cultural context of Noh for this study is set up as a medieval Japanese world view, which is an enchanted world with blurred boundaries between the visible and invisible world, human and non-human, sentient and non-sentient, enlightened and conditioned. The introduction traces the religious and ritual origins of Noh theater, and establishes the characteristics of the genre that make it possible for Noh to be offered up as an alternative to the mainstream ritual, and proposes an analysis of this ritual through dynamic and evolving schemes of ritualization and mythmaking, rather than ritual as a superimposed structure. -

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan Robert Goree, Wellesley College Abstract The cartographic history of Japan is remarkable for the sophistication, variety, and ingenuity of its maps. It is also remarkable for its many modes of spatial representation, which might not immediately seem cartographic but could very well be thought of as such. To understand the alterity of these cartographic modes and write Japanese map history for what it is, rather than what it is not, scholars need to be equipped with capacious definitions of maps not limited by modern Eurocentric expectations. This article explores such classificatory flexibility through an analysis of the mapping function of meisho zue, popular multivolume geographic encyclopedias published in Japan during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The article’s central contention is that the illustrations in meisho zue function as pictorial maps, both as individual compositions and in the aggregate. The main example offered is Miyako meisho zue (1780), which is shown to function like a map on account of its instrumental pictorial representation of landscape, virtual wayfinding capacity, spatial layout as a book, and biased selection of sites that contribute to a vision of prosperity. This last claim about site selection exposes the depiction of meisho as a means by which the editors of meisho zue recorded a version of cultural geography that normalized this vision of prosperity. Keywords: Japan, cartography, Akisato Ritō, meisho zue, illustrated book, map, prosperity Entertaining exhibitions arrayed on the dry bed of the Kamo River distracted throngs of people seeking relief from the summer heat in Tokugawa-era Kyoto.1 By the time Osaka-based ukiyo-e artist Takehara Shunchōsai (fl. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

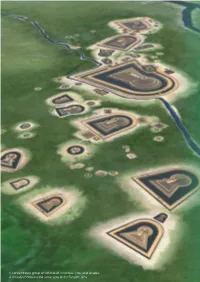

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples

Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History Vol. 179 November 2013 Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples YOSHIKAWA Shinji The abandoned temple of Okuyama (Okuyama Kumedera Temple) located at Okuyama in Asuka Village, Nara Prefecture is considered to be an old temple founded in the 620s or 630s, and identified with the Oharidadera Temple found in bibliographical sources of olden times. However, with regard to the circumstances of the foundation of the Oharidadera Temple, to date, no firmly established theory has been formed. In this paper by rereading historical materials relating to ancient times through to the medieval period, the following conclusions were obtained. 1. Oharidadera Temple in Asuka was the leading convent in the late 7th century, and even in the 8th century the temple had a close relation with the Imperial Family. It was confirmed that concurrently with the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo, the temple was moved to the northern outskirts of Heijyo-kyo, and the new temple was also called Oharidadera. 2. The Taikoji Temple in Nara, mentioned in historical materials covering the Heian period and later, in view of its geographical position, can be assumed to be the same as the Heijyo Oharidadera Temple. It would be reasonable to consider that Oharidadera Temple had the Buddhist name, Taikoji, since before the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo. 3. Private estates owned by Taikoji Temple in Yamato Province, mentioned in the Kanyo Ruijusho collection, were systematically arranged in locations convenient for overland transportation on the Nakatsu-Michi road and water transport on the Yamato River; against this background a strong admin- istrative and financial power can be inferred. -

Migration and Networks in Early Modern Kyoto, Japanã

IRSH 47 (2002), pp. 243–259 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859002000597 # 2002 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Migration and Networks in Early Modern Kyoto, Japanà Mary Louise Nagata Summary: The question of assimilation networks for migrants is usually applied to international migration. In this study, however, I use the population registers for a neighborhood in early modern Kyoto to look for possible network connections in domestic migration. I found a yearly turnover of fourteen households moving in and out of the neighborhood. Household and group migration was more important than individual migration and there is some sign of primary–secondary migration flows. Service migration did not play a major role in the migration patterns of this neighborhood, but the textile industry was probably an important attraction. Evidence of networks appears in the use of shop names that reflect a connection with a province or some specific location. These shop names usually reflected the place of origin of the household and may have been an effective method of gaining network connections and the guarantors necessary for finding housing and employment. INTRODUCTION The study of assimilation networks is a major topic in the study of international migration. The immigrant, far from home and often speaking a language different from the local population, frequently relies upon a network of contacts to settle into his new home. This network is often a local subcommunity with ties to the home country of the immigrant and shares language, culture, and religious affiliations with the immigrant. Such networks often help the immigrant find housing, employment and access to essential services that facilitate his survival and assimilation into the new community.1 While assimilation networks are an important aspect of the study of à I was able to collect this data with the support of the EurAsian Project on Population and Family History, under the leadership of Akira Hayami at International Research Center for Japanese Studies, with the help of Kiyoshi Hamano.