The Signal Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statewide Logistics Plan for North Carolina

Statewide Logistics Plan for North Carolina An Investigation of the Issues with Recommendations for Action APPENDICES By George F. List, Ph.D, P.E. P.I. and Head, Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering North Carolina State University Robert S. Foyle, P.E. Co-P.I. and Associate Director, ITRE North Carolina State University Henry Canipe Senior Manager TransTech Management, Inc. John Cameron, Ph.D. Managing Partner TransTech Management, Inc. Erik Stromberg Ports and Harbors Practice Leader Hatch, Mott, MacDonald LLC For the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management May 13, 2008 Appendices Appendix A: Powerpoint Slide Sets Presentations include: Tompkins Associates North Carolina Statewide Logistics Proposal North Carolina Statewide Logistics Plan Cambridge Systematics Freight Demand and Logistics – Trends and Issues Highway Freight Transportation – Trends and Issues Rail Freight Transportation – Trends and Issues Waterborne Freight Transportation – Trends and Issues State DOTs and Freight – Trends and Issues Virginia Statewide Multimodal Freight Study - Phase I Overview Global Insight Shifts in Global Trade Patterns – Meaning for North Carolina 5/5/2008 North Carolina Statewide Logistics Proposal Presented to: North Carolina State University Project Team Charlotte, NC March 13, 2008 Caveat… This presentation and discussion is from the Shipper’s perspective… ASSO C I ATES CONFIDENTIAL — Use or disclosure of this information is restricted. 2 1 5/5/2008 North American Port Report (1/08) A majority of the Supply Chain Consortium respondents to the North American Port Report survey believe that their supply chain network is not optimal with respect to the ports used for their ocean freight. Significant opportunities exist from getting all aspects of the supply chain aligned to optimizing costs and customer service. -

Freight Car Line Companies 12-13 North Carolina Department of Revenue

IA-336 Web Freight Car Line Companies 12-13 North Carolina Department of Revenue Application Beginning Ending DOR Use Only for Period (MM-DD-YY) (MM-DD-YY) Legal Name (First 35 Characters) (USE CAPITAL LETTERS FOR YOUR NAME AND ADDRESS) Trade Name Federal Employer ID Number Mailing Address City State Zip Code Fill in applicable circles: Name of Contact Person State of Domicile Amended Return Corporation is a first-time filer in N.C. Phone Number Fax Number Address has changes since prior year Part 1. Computation of Gross Earnings Taxes In Lieu of Ad Valorem Taxes 1. Total Revenue from the Operation of Freight Cars Within North Carolina 1. (From Part 2, Page 2) , , .00 2. Tax Due 2. Multiply Line 1 by 3% , , .00 3. Penalty (10% for late payment; 5% per month, maximum 25%, for late filing) 3. Multiply Line 2 by rate above if return with full payment is not filed timely. , .00 4. Interest (See the Department’s website, www.dornc.com, for current interest rate.) 4. Multiply Line 2 by applicable rate if return with full payment is not filed timely. , .00 5. Total Due 5. Add Lines 2 through 4 $ , , .00 Signature: Title: Date: I certify that, to the best of my knowledge, this return is accurate and complete. Signature of Preparer Preparer’s other than Taxpayer: FEIN, SSN, or PTIN: This return is used to report gross earnings from the operation of freight cars within North Carolina by a person operating cars, furnishing cars, or leasing cars for the transportation of freight in North Carolina. -

Download the Regional Freight Mobility Plan

GREATER CHARLOTTE REGIONAL FREIGHT MOBILITY PLAN Prepared for: Prepared by: December 2016 GREATER CHARLOTTE REGIONAL FREIGHT MOBILITY PLAN i Final Report • Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 2 The Purpose of This Freight Plan .............................................................................................. 2 3 Regional Collaboration ............................................................................................................ 2 4 Three Pillars of This Freight Plan .............................................................................................. 4 4.1 Population Trends .................................................................................................................. 4 4.2 Economic Indicators............................................................................................................... 5 4.3 Transportation System Conditions ........................................................................................ 7 5 Plan Development ................................................................................................................... 9 6 Stakeholder Engagement Process .......................................................................................... 11 6.1.1 Coordinating Committee ......................................................................................... 11 6.1.2 Steering Committee ................................................................................................ -

The Signal Bridge

THE SIGNAL BRIDGE NEWSLETTER OF THE MOUNTAIN EMPIRE MODEL RAILROADERS CLUB JULY 2015 - MEMBERS EDITION Volume 22 – Number 7 Published for the Education and Information of Its Membership CLUB OFFICERS EAST TENNESSEE & WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA President: RAILROAD COMPANY Fred Alsop TRAIN ORDER FOR THE FINAL RUN OCTOBER 16,1950 [email protected] Vice-President John Carter [email protected] Treasurer: Gary Emmert [email protected] Secretary: Debbi Edwards [email protected] Newsletter Editor: Ted Bleck-Doran [email protected] Webmasters: John Edwards [email protected] Bob Jones [email protected] LOCATION ETSU Campus George L. Carter Railroad Museum HOURS Business Meetings are held the 3rd Tuesday of each month. Meetings start at 6:30 PM in: Brown Hall Room 312 ETSU Campus, Johnson City, TN. Open House for viewing every Saturday from 10:00 am until 3:00 pm. Work Nights are held each HE LAST RUN OF THE TWEETSIE CONSISTED OF AN EXCURSION TRAIN FROM ELIZABETHTON TO CRANBERRY Thursday from 4:00 pm AND RETURN – TRAIN ORDER WAS SIGNED BY CY CRUMELY (CONDUCTOR) AND WILLIAM ALLISON until ?? (ENGINEER) – ENGINE No. 11 WAS USED FOR THE MOVE. THE SIGNAL BRIDGE JULY 2015 diesel behind it. The practice of pushing the steam engines STONE MOUNTAIN, GEORGIA ended in 2002, and they remained within the yard until being DAUGHTER’S FIRST RAILFAN ADVENTURE donated to other tourist railroads or museums, the first PHOTOS CONTRIBUTED BY HOBIE HYDER leaving the railroad in 2008, followed by the remaining two BACKGROUND FROM WIKIPEDIA.ORG in 2013. Hobie Hyder recently took the family on an outing to Stone Mountain Georgia and the Southeastern Railroad Museum. -

North Carolina Railroad System Map-August 2019

North Carolina !( Railroad System Clover !( !( South Boston Franklin Danville !( !( !( Mount Airy !( !( Clarksville Alleghany Eden !( Mayo Currituck Camden Ashe Hyco !( !( Gates !( Roanoke !( Conway Surry YVR Norlina Weldon R Stokes Rockingham Granville Rapids Elizabeth CA Caswell Person Vance !( Hertford City !( Roxboro Northampton !( Reidsville !( !( YVRR Oxford Henderson Warren Halifax !(Ahoskie VA Rural NC Watauga Wilkes !( Pasquotank Hall CA !( !( Erwin!( Yadkin Orange Kelford Chowan Perquimans North Durham Guilford !( N Franklin Avery Wilkesboro Forsyth !( Burlington Butner !( CDOT Mitchell ! Bertie !( Winston ! !(Hillsborough Franklinton Edenton Salem Greensboro Nash Caldwell ! Durham Rocky Midway !( High !( Wake Forest CLNA !(Taylorsville Iredell Davie ! Alamance !( ! Mount Yancey Lenoir Davidson Spring ! Madison !( Point Carrboro !( !( Tarboro Washington Alexander A Wake Burke C R Hope !( W C C T Zebulon Plymouth Tyrrell Y O !( Edgecombe !( Statesville !( D Cary CLNA Middlesex Lexington C !( !( !( Parmele Dare N ! W ! W Martin s Buncombe !( Hickory ! S !( S ain Chatham Raleigh Wendell t S n McDowell !( Morganton S !(Apex ! ou CMLX Marion !( k !Wilson M c rk Asheboro NHVX ky a Haywood !( !( o Pitt o P T Newton ! A l Salisbury n !( Wilson f m a O New Hll l !(Clayton N S n Old Fort Catawba !( L CLNA D t o m i CMIZ Denton u a t !( CLNA C C Greenville re a BLU Rowan Randolph u !( N Asheville G G N C !( W !( !( Belhaven Swain !( S !( Fuquay-Varina !( S !( Waynesville BLU A ! Washington !( GSM Lincoln Lincolnton ! T Selma Chocowinity -

George E. Tillitson Collection on Railroads M0165

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1j49n53k No online items Guide to the George E. Tillitson Collection on Railroads M0165 Department of Special Collections and University Archives 1999 ; revised 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the George E. Tillitson M0165 1 Collection on Railroads M0165 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: George E. Tillitson collection on railroads creator: Tillitson, George E. Identifier/Call Number: M0165 Physical Description: 50.5 Linear Feet(9 cartons and 99 manuscript storage boxes) Date (inclusive): 1880-1959 Abstract: Notes on the history of railroads in the United States and Canada. Conditions Governing Access The collection is open for research. Note that material is stored off-site and must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. Provenance Gift of George E. Tillitson, 1955. Special Notes One very useful feature of the material is further described in the two attached pages. This is the carefully annotated study of a good many of the important large railroads of the United States complete within their own files, these to be found within the official state of incorporation. Here will be included page references to the frequently huge number of small short-line roads that usually wound up by being “taken in” to the larger and expending Class II and I roads. Some of these files, such as the New York Central or the Pennsylvania Railroad are very big themselves. Michigan, Wisconsin, Oregon, and Washington are large because the many lumber railroads have been extensively studied out. -

North Carolina Rail Fast Facts for 2019 Freight Railroads …

Freight Railroads in North Carolina Rail Fast Facts For 2019 Freight railroads ….............................................................................................................................................................23 Freight railroad mileage …..........................................................................................................................................2,847 Freight rail employees …...............................................................................................................................................1,966 Average wages & benefits per employee …...................................................................................................$121,570 Railroad retirement beneficiaries …......................................................................................................................9,800 Railroad retirement benefits paid ….....................................................................................................................$234 million U.S. Economy: According to a Towson University study, in 2017, America's Class I railroads supported: Sustainability: Railroads are the most fuel efficient way to move freight over land. It would have taken approximately 4.6 million additional trucks to handle the 82.7 million tons of freight that moved by rail in North Carolina in 2019. Rail Traffic Originated in 2019 Total Tons: 13.2 million Total Carloads: 284,600 Commodity Tons (mil) Carloads Chemicals 3.2 33,800 Nonmetallic Minerals 3.1 30,200 Intermodal -

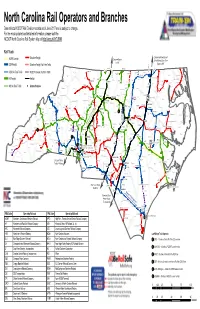

North Carolina Rail Operators and Branches Data Reflects NCDOT Rail Division Records As of June 2017 and Is Subject to Change

North Carolina Rail Operators and Branches Data reflects NCDOT Rail Division records as of June 2017 and is subject to change. For the most updated and detailed information, please visit the NCDOT North Carolina Rail System Map at http://arcg.is/1hTuBMI E Rail Track E NCRR Corridor Shortline Freight Carolinian/Palmetto and Crescent Route Silver Meteor/Silver Star To NYC ) Route to NYC CSX Freight Shortline Freight, No Train Traffic A A S NS(DW) NS(MAY) ( ) ) X A NS(L) S (S D X C YVRR(GW) F S CSX, No Train Traffic Alleghany CSX(S) C NCDOT-Owned, No Train Traffic N ( NS(HYC) NS(D) Ashe S CSX(SA) Gates Camden N Northampton Surry Stokes WELDON .! Currituck NS Freight Amtrak NS(R) Rockingham Caswell Vance Warren Pasquotank YVRR(CF) NS (MAIN) NS(L) Hertford OXFORD ! CA(NS) Person . CSX(A) (! YVRR(K) Granville NCVA NS, No Train Traffic Amtrak Stations Halifax Watauga Wilkes NS(D) Perquimans .! KELFORD Yadkin R) Durham ( NS(H) Orange UNK NS(K) ) Mitchell Avery Forsyth .! BURLINGTON P UNK(SB) LOUISBURG CCX Terminal (! D .! WINSTON-SALEM ( Bertie Chowan (! S GREENSBORO Franklin !¾ Guilford N CSX(Z) Alamance (! NS(L) CLNA(ABA) ROCKY MOUNT Caldwell Davidson (! DURHAM UNK(ABA) ARC E NS(J) CSX(S) LENOIR Davie r (! Nash CSX(AB) Madison Yancey .! CWCY(HG) o HIGH POINT Alexander d ri e 3 CSX(ABC) NS(S) r tt NS(M) lo ) Edgecombe o r ) Washington Iredell C a S Tyrrell D Wake Martin t h D CLNA(NS) Dare C D S ( NS(S) NS(S) n ( (! to (! ) WSS(W) K o X h RALEIGH A S McDowell .! m g N CARY Buncombe i WILSON A C ( .!MARION Burke HICKORY d le U (! e a X NS(L) i ) NS(H) Wilson CMLX(CM) R S NS(PM) P !ASHEBORO Chatham NHVX S . -

Report of the Corporation Commission for the Biennial Period

,North Carolina State Libraiy. Ralwgh STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA <c TWENTY-SIXTH REPORT CORPORATION COMMISSION BIENNIAL PERIOD, 1931-1932 COMPILATION FROM RAILROAD RETURNS ARE FOR YEARS ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1930 AND 1931 % m¥> H^.A STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA CORPORATIOJN^ COMMISSIOlSr W. T. LEE, Chaieman GEORGE P. PELL STANLEY WINBORNE COAIMISWiOiNKRS R. O- Self, Clerk Rebecca Mekeitt, Reporter- Elsie G. Riddtok, Assistant Clerk Maey Shaw, Stenographer Edgar Womble, Statistician RATE DEPARTMENT W. G. Womjjle, Director of Railroad Trans imrtation Needham B, C0RRE1.L, Rate Specialist C. H. Noah, Junior Rate Specialist CAPITAL ISSUES DEPARTMENT Stanley Winborne, Commissioner Sophia P. Busbhp:, Stenographer — LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Raleigh, December 5, 1932. His Excellency, O. Max Gardner, Governor of North Carolin'O., Raleigh, N. C. Sir:—As required by Section 1065, Chapter 21, Consolidated Statutes, the Corporation Commission has the honor to report for the biennial period 1931 and 1932. The 1931 Legislature passed Chapter 455, of the Public Laws, which materially amended Chapter 21, Article III, Volume I, Consolidated Statutes, by giving this Commission authority to require uniform ac- counting, annual and other reports, make ex parte investigations, require certificates of convenience and necessity for the transfer of public utility property, and to a])prove contracts between utilities and holding Com- panies. Electric Kates This Commission has had jurisdiction of ehn-tric, gas and telephone utilities since 1913, Practically all the utilities operating in the State at the present time were at that time operating and had many of the plants that are in operation today already in service at the time that the Com- mission obtained jurisdiction. -

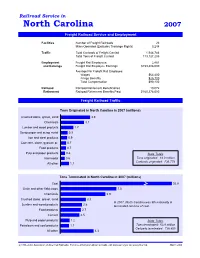

NC Railroad Statistics (2007)

Railroad Service in North Carolina 2007 Freight Railroad Service and Employment Facilities Number of Freight Railroads 23 Miles Operated (Excludes Trackage Rights) 3,248 Traffic Total Carloads of Freight Carried 1,544,783 Total Tons of Freight Carried 113,127,205 Employment Freight Rail Employees 2,481 and Earnings Freight Rail Employee Earnings $159,886,000 Average Per Freight Rail Employee: Wages $64,400 Fringe Benefits $25,700 Total Compensation $90,100 Railroad Railroad Retirement Beneficiaries 10,072 Retirement Railroad Retirement Benefits Paid $160,378,000 Freight Railroad Traffic Tons Originated in North Carolina in 2007 (millions) Crushed stone, gravel, sand 3.9 Chemicals 3.1 Lumber and wood products 1.7 Scrap paper and scrap metal 0.9 Iron and steel products 0.9 Concrete, stone, gypsum pr. 0.7 Food products 0.7 Pulp and paper products 0.6 State Totals Intermodal 0.6 Tons originated: 14.0 million Carloads originated: 236,779 All other 1.1 Tons Terminated in North Carolina in 2007 (millions) Coal 32.8 Grain and other field crops 7.3 Chemicals 5.9 Crushed stone, gravel, sand 3.3 In 2007, North Carolina was 9th nationally in Lumber and wood products 2.8 terminated rail tons of coal. Food products 2.7 Cement 2.5 Pulp and paper products 1.2 State Totals Petroleum and coal products 1.1 Tons terminated: 63.9 million Carloads terminated: 738,850 All other 4.3 © 1993–2009, Association of American Railroads. For more information about railroads, visit www.aar.org or call 202-639-2100. March 2009 Freight Railroads in North Carolina 2007 Miles of Railroad North Carolina Miles Operated Operated in North Carolina Totals Number Excluding Including Class I Railroads of Freight Trackage Trackage CSX Transportation 1,121Railroads Rights Rights Norfolk Southern Corp. -

North Carolina Rail Track – 3Rd Quarter 2021 - North Carolina Department of Transportation SDE Feature Class

North Carolina Rail Track – 3rd Quarter 2021 - North Carolina Department of Transportation SDE Feature Class Tags Track, Transportation, Rail, Railroad, Rail Lines, Rail Track Summary This dataset is made available to provide a representation of state-maintained railroad track for mapping and planning purposes. Description The dataset provided includes line data for use in geographic information systems that represents all the standard gauge freight and passenger railroad track in North Carolina, and contains the following information: owner, operator, branch, beginning milepost, ending milepost, and in service status. The linework was digitized based on the most recent statewide aerial photography provided by the State of North Carolina. Select areas of inactive track have been added to the dataset to aid in preserved and future corridor analysis. Credits North Carolina Department of Transportation Rail Division, Moffatt & Nichol Engineers, Simpson Engineers and Associates Use limitations The North Carolina Department of Transportation shall not be held liable for any errors in this data. This includes errors of omission, commission, errors concerning the content of the data, and relative and positional accuracy of the data. This data cannot be construed to be a legal document. Primary sources from which this data was compiled must be consulted for verification of information contained in this data. Extent West -84.127195 East -76.089531 North 36.607291 South 33.839590 Scale Range Maximum (zoomed in) 1:5,000 Minimum (zoomed out) 1:150,000,000 -

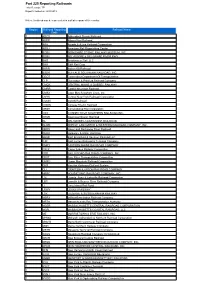

Part 225 Reporting Railroads.Pdf

Part 225 Reporting Railroads Total Records: 771 Report Created on: 4/30/2019 Notes: A railroad may be represented in multiple regions of the country. Region Railroad Reporting Railroad Name Code 1 ADCX Adirondack Scenic Railroad 1 APRR Albany Port Railroad 1 ARA Arcade & Attica Railroad Corporation 1 ARDJ American Rail Dispatching Center 1 BCRY BERKSHIRE SCENIC RAILWAY MUSEUM, INC. 1 BDRV BELVEDERE & DELAWARE RIVER RWY 1 BHR Brookhaven Rail, LLC 1 BHX B&H Rail Corp 1 BKRR Batten Kill Railroad 1 BSOR BUFFALO SOUTHERN RAILROAD, INC. 1 CDOT Connecticut Department Of Transportation 1 CLP Clarendon & Pittsford Railroad Company 1 CMQX CENTRAL MAINE & QUEBEC RAILWAY 1 CMRR Catskill Mountain Railroad 1 CMSX Cape May Seashore Lines, Inc. 1 CNYK Central New York Railroad Corporation 1 COGN COGN Railroad 1 CONW Conway Scenic Railroad 1 CRSH Consolidated Rail Corporation 1 CSO CONNECTICUT SOUTHERN RAILROAD INC. 1 DESR Downeast Scenic Railroad 1 DL DELAWARE LACKAWANNA RAILROAD 1 DLWR DEPEW, LANCASTER & WESTERN RAILROAD COMPANY, INC. 1 DRRV Dover and Rockaway River Railroad 1 DURR Delaware & Ulster Rail Ride 1 EBSR East Brookfield & Spencer Railroad LLC 1 EJR East Jersey Railroad & Terminal Company 1 EMRY EASTERN MAINE RAILROAD COMPANY 1 FGLK Finger Lakes Railway Corporation 1 FRR FALLS ROAD RAILROAD COMPANY, INC. 1 FRVT Fore River Transportation Corporation 1 GMRC Green Mountain Railroad Corporation 1 GRS Pan Am Railways/Guilford System 1 GU GRAFTON & UPTON RAILROAD COMPANY 1 HRRC HOUSATONIC RAILROAD COMPANY, INC. 1 LAL Livonia, Avon & Lakeville Railroad Corporation 1 LBR Lowville & Beaver River Railroad Company 1 LI Long Island Rail Road 1 LRWY LEHIGH RAILWAY 1 LSX LUZERNE & SUSQUEHANNA RAILWAY 1 MBRX Milford-Bennington Railroad Company 1 MBTA Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority 1 MCER MASSACHUSETTS CENTRAL RAILROAD CORPORATION 1 MCRL MASSACHUSETTS COASTAL RAILROAD, LLC 1 ME MORRISTOWN & ERIE RAILWAY, INC.