RPS Lecture 2010 Alex Ross

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waltz from the Sleeping Beauty

Teacher Workbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Jessica Nalbone .................................................................................2 Director of Education, North Carolina Symphony Information about the 2012/13 Education Concert Program ............................3 North Carolina Symphony Education Programs .................................................4 Author Biographies ..............................................................................................6 Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) .......................................................................................7 Oriental Festival March from Aladdin Suite, Op. 34 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) ..........................................................15 Symphony No. 39 in E-flat Major, K.543, Mvt. I or III (Movements will alternate throughout season) Claude Debussy (1862-1918) ..............................................................................28 “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk” from Children’s Corner, Suite for Orchestra Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) ..................................................................33 Waltz from The Sleeping Beauty Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) ...............................................................................44 “Dance of the Young Girls” from The Rite of Spring Loonis McGlohon (1921-2002) & Charles Kuralt (1924-1997) ..........................52 “North Carolina Is My Home” Richard Wagner (1813-1883) ..............................................................................61 Overture to Rienzi -

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

An Analysis of How Audiences Respond to Rhetorical Devices in Political Speeches

This is a repository copy of Claps and Claptrap: : An analysis of how audiences respond to rhetorical devices in political speeches. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/100468/ Version: Published Version Article: Bull, Peter orcid.org/0000-0002-9669-2413 (2016) Claps and Claptrap: : An analysis of how audiences respond to rhetorical devices in political speeches. Journal of Social and Political Psychology. pp. 473-492. Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Journal of Social and Political Psychology jspp.psychopen.eu | 2195-3325 Review Articles Claps and Claptrap: The Analysis of Speaker-Audience Interaction in Political Speeches Peter Bull* a [a] Department of Psychology, University of York, York, United Kingdom. Abstract Significant insights have been gained into how politicians interact with live audiences through the detailed microanalysis of video and audio recordings, especially of rhetorical techniques used by politicians to invite applause. The overall aim of this paper is to propose a new theoretical model of speaker-audience interaction in set-piece political speeches, based on the concept of dialogue between speaker and audience. -

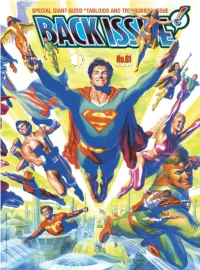

Dec. 2012 $10.95

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

No.61 2 1 0 2

D e c . 2 0 1 2 No.61 $10.95 Legion of Super-Heroes TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Rights All Comics. DC © & TM Super-Heroes of Legion Volume 1, Number 61 December 2012 EDITOR-IN- CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER FLASHBACK: The Perils of the DC/Marvel Tabloid Era . .1 Rob Smentek Pitfalls of the super-size format, plus tantalizing tabloid trivia SPECIAL THANKS BEYOND CAPES: You Know Dasher and Dancer: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Rein- Jack Abramowitz Dan Jurgens deer . .7 Neal Adams Rob Kelly and The comics comeback of Santa and the most famous reindeer of all Erin Andrews TreasuryComics.com FLASHBACK: The Amazing World of Superman Tabloids . .11 Mark Arnold Joe Kubert A planned amusement park, two movie specials, and your key to the Fortress Terry Austin Paul Levitz Jerry Boyd Andy Mangels BEYOND CAPES: DC Comics’ The Bible . .17 Rich Bryant Jon Mankuta Kubert and Infantino recall DC’s adaptation of the most spectacular tales ever told Glen Cadigan Chris Marshall FLASHBACK: The Kids in the Hall (of Justice): Super Friends . .24 Leslie Carbaga Steven Morger A whirlwind tour of the Super Friends tabloid, with Alex Toth art Comic Book Artist John Morrow Gerry Conway Thomas Powers BEYOND CAPES: The Secrets of Oz Revealed . .29 DC Comics Alex Ross The first Marvel/DC co-publishing project and its magical Marvel follow-up Paul Dini Bob Rozakis FLASHBACK: Tabloid Team-Ups . .33 Mark Evanier Zack Smith The giant-size DC/Marvel crossovers and their legacy Jim Ford Bob Soron Chris Franklin Roy Thomas INDEX: Bronze Age Tabloids Checklist . -

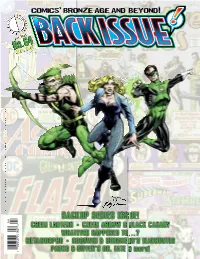

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard . -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

On the Road with President Woodrow Wilson by Richard F

On the Road with President Woodrow Wilson By Richard F. Weingroff Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................... 2 Woodrow Wilson – Bicyclist .................................................................................. 1 At Princeton ............................................................................................................ 5 Early Views on the Automobile ............................................................................ 12 Governor Wilson ................................................................................................... 15 The Atlantic City Speech ...................................................................................... 20 Post Roads ......................................................................................................... 20 Good Roads ....................................................................................................... 21 President-Elect Wilson Returns to Bermuda ........................................................ 30 Last Days as Governor .......................................................................................... 37 The Oath of Office ................................................................................................ 46 President Wilson’s Automobile Rides .................................................................. 50 Summer Vacation – 1913 ..................................................................................... -

Gestures: Your Body Speaks

GESTURES: YOUR BODY SPEAKS How to Become Skilled WHERE LEADERS in Nonverbal Communication ARE MADE GESTURES: YOUR BODY SPEAKS TOASTMASTERS INTERNATIONAL P.O. Box 9052 • Mission Viejo, CA 92690 USA Phone: 949-858-8255 • Fax: 949-858-1207 www.toastmasters.org/members © 2011 Toastmasters International. All rights reserved. Toastmasters International, the Toastmasters International logo, and all other Toastmasters International trademarks and copyrights are the sole property of Toastmasters International and may be used only with permission. WHERE LEADERS Rev. 6/2011 Item 201 ARE MADE CONTENTS Gestures: Your Body Speaks............................................................................. 3 Actions Speak Louder Than Words...................................................................... 3 The Principle of Empathy ............................................................................ 4 Why Physical Action Helps........................................................................... 4 Five Ways to Make Your Body Speak Effectively........................................................ 5 Your Speaking Posture .................................................................................. 7 Gestures ................................................................................................. 8 Why Gestures? ...................................................................................... 8 Types of Gestures.................................................................................... 9 How to Gesture Effectively.......................................................................... -

Romans on Parade: Representations of Romanness in the Triumph

ROMANS ON PARADE: REPRESENTATIONS OF ROMANNESS IN THE TRIUMPH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Amber D. Lunsford, B.A., M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Erik Gunderson, Adviser Professor William Batstone Adviser Professor Victoria Wohl Department of Greek and Latin Copyright by Amber Dawn Lunsford 2004 ABSTRACT We find in the Roman triumph one of the most dazzling examples of the theme of spectacle in Roman culture. The triumph, though, was much more than a parade thrown in honor of a conquering general. Nearly every aspect of this tribute has the feel of theatricality. Even the fact that it was not voluntarily bestowed upon a general has characteristics of a spectacle. One must work to present oneself as worthy of a triumph in order to gain one; military victories alone are not enough. Looking at the machinations behind being granted a triumph may possibly lead to a better understanding of how important self-representation was to the Romans. The triumph itself is, quite obviously, a spectacle. However, within the triumph, smaller and more intricate spectacles are staged. The Roman audience, the captured people and spoils, and the triumphant general himself are all intermeshed into a complex web of spectacle and spectator. Not only is the triumph itself a spectacle of a victorious general, but it also contains sub-spectacles, which, when analyzed, may give us clues as to how the Romans looked upon non-Romans and, in turn, how they saw themselves in relation to others. -

Charitable Irish Society 3-17-16.Revised by Dermaid Ferriter

THE CHARITABLE IRISH SOCIETY Founded 1737 279th Anniversary Dinner March 17, 2016 Omni Parker House - Boston, Massachusetts PRESIDENT'S WELCOME, CHRISTOPHER A. DUGGAN MR. DUGGAN: Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. Good evening. Why don't we get the festivities underway. Good evening and a very, very Happy Saint Patrick's Day to everybody here. This is our 279th Anniversary. (Applause.) MR. DUGGAN: And we have the oldest Irish society in the Americas. Now, some of you may have heard this, I certainly did, that the loyal and friendly sons of St. Patrick in Philadelphia just celebrated their 245th Anniversary. And it was announced in the Irish Times that Ambassador Anne Anderson was going to be their -- inducted this year as their first woman member. Our response to that was it's a little bit late, but I'd also announce that this was the oldest Irish society in America. And immediately after that came out, I received about 450 e-mails and text messages asking me to set them straight on that, that we were some 40 years older than that, so I did, and their President, John Hannon, and I have become good friends as a result and so I did mention that it was great that they -- we had women members now for 50 years and we thought we were late, but good for them. But, anyway, are you all having a good time so far? (Applause.) MR. DUGGAN: Well, you're all drinking, is that it? Well, you know, intoxication is pretty good, but there are a lot of ways to get intoxicated, right? Not as many of them as good as drinking. -

Bodies in Transition. Queering the Comic Book Superhero

QUEER(ING) POPULAR CULTURE BODIES IN TRANSITION Queering the Comic Book Superhero BY DANIEL STEIN ABSTRACT This essay analyzes the comic book superhero as a popular figure whose queer- ness follows as much from the logic of the comics medium and the aesthetic prin- ciples of the genre as it does from a dialectic tension between historically evolving heteronormative and queer readings. Focusing specifically on the superbody as an overdetermined site of gendered significances, the essay traces a shift from the ostensibly straight iterations in the early years of the genre to the more recent appearance of openly queer characters. It further suggests that the struggle over the superbody’s sexual orientation and gender identity has been an essential force in the development of the genre from its inception until the present day. The comic book superhero has been a figure of the popular imagination for eight decades, if we count Superman’s appearance in Action Comics #1 (June 1938) as the beginning of the genre. Almost as old as the genre itself are associations of the superhero with what the American amateur psychologist Gershon Legman de- scribed as »an undercurrent of homosexuality and sado-masochism«1 in his book Love and Death (1949). These associations became part of the broader public dis- course when the German-born psychiatrist Frederic Wertham expanded on them in Seduction of the Innocent (1954), a flawed but popular study of the effects of comic-book reading on juveniles that played into the climate of sexual anxieties at the height of the so-called comics scare.