ETHJ Vol-36 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's Favorite Pastime

America’s favorite pastime Birmingham-Southern College has produced a lot exhibition games against major league teams, so Hall of talent on the baseball field, and Fort Worth Cats of Famers like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe shortstop Ricky Gomez ’03 is an example of that tal- DiMaggio, Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pee ent. Wee Reese,Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Hank Gomez, who played on BSC’s 2001 NAIA national Aaron all played exhibition games at LaGrave Field championship team, is in his second year with the against the Cats. Cats, an independent professional minor league club. Gomez encourages BSC faithful to visit Fort Prior to that, he played for two years with the St. Worth to see a game or two. Paul Saints. “It is a great place to watch a baseball game and The Fort Worth Cats play in the Central Baseball there is a lot to do in Fort Worth.” League. The team has a rich history in baseball He also attributes much of his success to his expe- going back to 1888. The home of the Cats, LaGrave riences at BSC. Field, was built in 2002 at the same location of the “To this day, I talk to my BSC teammates and to old LaGrave Field (1926-67). Coach Shoop [BSC Head Coach Brian], who was Many famous players have worn the uniform of not only a great coach, but a father figure. the Cats including Maury Wills and Hall of Famers Birmingham-Southern has a great family atmos- Rogers Hornsby, Sparky Anderson, and Duke Snider. -

Prior Player Transfers

American Association Player Transfers 2020 AA Team Position Player First Name Player Last Name MLB Team Kansas City T-Bones RHP Andrew DiPiazza Colorado Rockies Chicago Dogs LHP Casey Crosby Los AngelesDodgers Lincoln Saltdogs RHP Ricky Knapp Los AngelesDodgers Winnipeg Goldeyes LHP Garrett Mundell Milwaukee Brewers Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks RHP Grant Black St. LouisCardinals Kansas City T-Bones RHP Akeem Bostick St. LouisCardinals Chicago Dogs LHP D.J. Snelten Tampa BayRays Sioux City Explorers RHP Ryan Newell Tampa BayRays Chicago Dogs INF Keon Barnum Washington Nationals Sioux City Explorers INF Jose Sermo Pericos de Puebla Chicago Dogs OF David Olmedo-Barrera Pericos de Puebla Sioux City Explorers INF Drew Stankiewicz Toros de Tijuana Gary SouthShore Railcats RHP Christian DeLeon Toros de Tijuana American Association Player Transfers 2019 AA Team Position Player First Name Player Last Name MLB Team Sioux City Explorers RHP Justin Vernia Arizona Diamondbacks Sioux Falls Canaries RHP Ryan Fritze Arizona Diamondbacks Fargo-Moorhead RedHawks RHP Bradin Hagens Arizona Diamondbacks Winnipeg Goldeyes INF Kevin Lachance Arizona Diamondbacks Gary SouthShore Railcats OF Evan Marzilli Arizona Diamondbacks St. Paul Saints OF Max Murphy Arizona Diamondbacks Texas AirHogs INF Josh Prince Arizona Diamondbacks Texas AirHogs LHP Tyler Matzek Atlanta Braves Milwaukee Milkmen INF Angelo Mora BaltimoreOrioles Sioux Falls Canaries RHP Dylan Thompson Boston Red Sox Gary SouthShore Railcats OF Edgar Corcino Boston Red Sox Kansas City T-Bones RHP Kevin Lenik Boston Red Sox Gary SouthShore Railcats OF Colin Willis Boston Red Sox St. Paul Saints C Justin O’Conner Chicago White Sox Sioux City Explorers RHP James Dykstra CincinnatiReds Kansas City T-Bones LHP Eric Stout CincinnatiReds St. -

The Characteristics of Trauma

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Music and Trauma in the Contemporary South African Novel“ Verfasser Christian Stiftinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011. Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: UF Englisch Betreuer: Univ. Prof. DDr . Ewald Mengel Declaration of Authenticity I hereby confirm that I have conceived and written this thesis without any outside help, all by myself in English. Any quotations, borrowed ideas or paraphrased passages have been clearly indicated within this work and acknowledged in the bibliographical references. There are no hand-written corrections from myself or others, the mark I received for it can not be deducted in any way through this paper. Vienna, November 2011 Christian Stiftinger Table of Contents 1. Introduction......................................................................................1 2. Trauma..............................................................................................3 2.1 The Characteristics of Trauma..............................................................3 2.1.1 Definition of Trauma I.................................................................3 2.1.2 Traumatic Event and Subjectivity................................................4 2.1.3 Definition of Trauma II................................................................5 2.1.4 Trauma and Dissociation............................................................7 2.1.5 Trauma and Memory...……………………………………………..8 2.1.6 Trauma -

Port Aransas

Inside the Moon Kite Day A2 Island Spring A4 Botanical Gardens A7 Fishing A11 Remember When A16 Issue 829 The 27° 37' 0.5952'' N | 97° 13' 21.4068'' W Island Free The voiceMoon of The Island since 1996 March 5, 2020 Weekly www.islandmoon.com FREE Around Island Grocery Store Waterpark How the Island Voted The Island Going Up! Ride Nueces County Constable By Dale Rankin Precinct 4 (Runoff) Once upon a time on a beach not so Set to open by summer 2020 1123 (45%) Monty Allen far away Spring Breakers swarmed to Comes 1101 (44%) Robert Sherwood the beach north of Packery Channel By Dale Rankin space. Mr. Rasheed said a verbal between Zahn Road and Newport agreement has been reached to locate 269 (10.8%) John Bowers The 20,420 square-foot IGA grocery Pass. Cheek to jowl they lined the a Denny’s diner on a separate three- store under construction on South Down Padre Island totals beach with tents, couches, giant thousand square-foot site fronting Padre Island Drive south of Whitecap bonfires, and bags of trash, most of SPID. 7882 Total Padre Island which got left behind when they went Boulevard will be open by summer Registered Voters home. 2020, according to owners Lori and Mr. Rasheed said the IGA store will Moshin Rasheed. be roughly based on the design of a 2510 (32%) Total Padre Island Police flooded the area but to little Sprouts Farmer’s Market and will voters “We will have the equipment for avail as the revelers, very few of include walk-in coolers for produce the grocery store arriving in the Contested Races Republican which were actual college students, and meat with a butcher on duty, a next few weeks,” Mr. -

The Crusader Monthll,J Nelijsletter

THE CRUSADER MONTHLL,J NELIJSLETTER ROBERT F. WILLIAMS, EDITOR -IN EXILE- VoL . ~ - No. 9 MAY 1968 Afro-Americans & Slick John Kennedy Government of the United States is no government T~E of the Afro-Americans at all. The slick John Ken- nedy gang is operating one of the greatest sham govern- ment in the entire world. Afro-Americans and fair minded Od > ~- O THE wN«< /l~USL . lF Yov~Re EyER IN NE60, CALL ME AT whites must be gullible indeed to believe that the racist, KKK dominated so-called U.S. Government is concerned with the welfare and human rights of colored people. The colored people of the USA must bring themselves to realize that taken integration is a slick manuever to check the restlessness of an oppressed people fast becoming infect ed with the germ of total resistance policy developing among all of the oppressed peoples of the world. Token integration means nothing to the masses. Even an idiot should be able to see that so-called Token integration is no more than window dressing designed to lull the poor downtrodden Afro-American to sleep and to make the out side world think that the racist, savage USA is a fountainhead of social justice and democracy. The Afro-American in the USA is facing his greatest crisis since chattel slavery. All forms of violence and underhanded methods o.f extermination are being stepped up against our people. Contrary to what the "big daddies" and their "good nigras" would have us believe about all of the phoney progress they claim the race is making, the True status of the Afro-Ameri- can is s#eadily on the down turn. -

Cats Into Texas League Lead SHOOTING KING at 14 a WHALE! BUFFS BEATEN MEAGHER WILL A’S BEATEN LONG GAME LEAVE TODAY by ‘SAD SAM’

rrrrriMMMMMM < i mi nr i i#tf m f rf fM fifiMiMi»#iiUfrfrrfrfrirrrfrfrrffff rf f rtf rf t< —XN M The SPORTS I* BROWNSVILLE HERALD SECTION 1 mm * ~ — rr •fr-rrrffifrrrfiiTrrjifWifiiixMf ----rr‘r*‘i rri -rr rrrf »>»<»»»»»»»»»»>»»«»»»#»«HWWWWWMMMmm Stoner Hurls Cats Into Texas League Lead SHOOTING KING AT 14 A WHALE! BUFFS BEATEN MEAGHER WILL A’S BEATEN LONG GAME LEAVE TODAY BY ‘SAD SAM’ AN ALIVE. Cul- TEXAS LEAGUE Seems To Red used to Waco Makes It Possible By Greyhounds Begin Football Veteran Jones Results Monday Fort Worth 3. Houston 1. out plenty ol Practice Trouncing Spuds Monday Have Athletics’ Waco 9-10. Wichita Falls 3-4. vanishment o n Antorio 5. Twice Afternoon Number Shreveport 12. San .he gridiron lor How They Stand .iarlingen high, Clubs P. W. L. Pot. BY JACK LEBOW1TZ a of 23 62 37 25 .567 he is as ag- BY GAYLE TALBOT, Jr.. Back in 1915, youth years, Fort Worth SAN EENITO. 26.—Tile San made his bow .... 62 38 26 .581 in the Associated Press Sports Writer Aug. Samuel Pond Jones, Wichita Falls Saints have clinched as a me Benito the; to major league baseball Shreveport . 62 35 27 .565 nag as he was on Seven years after he pitched the Valley League championship by ber of the Cleveland Indians at a Houston . 61 34 27 A57 the it’s going grid, Fort Worth Cats to a Texas league defeating Donna Sunday by a score cost of $800. Frcm Cleveland he Waco 63 32 31 .506 a tough The Saints have been Dixie LU Stoner of 21-1. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Minor League Presidents

MINOR LEAGUE PRESIDENTS compiled by Tony Baseballs www.minorleaguebaseballs.com This document deals only with professional minor leagues (both independent and those affiliated with Major League Baseball) since the foundation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (popularly known as Minor League Baseball, or MiLB) in 1902. Collegiate Summer leagues, semi-pro leagues, and all other non-professional leagues are excluded, but encouraged! The information herein was compiled from several sources including the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd Ed.), Baseball Reference.com, Wikipedia, official league websites (most of which can be found under the umbrella of milb.com), and a great source for defunct leagues, Indy League Graveyard. I have no copyright on anything here, it's all public information, but it's never all been in one place before, in this layout. Copyrights belong to their respective owners, including but not limited to MLB, MiLB, and the independent leagues. The first section will list active leagues. Some have historical predecessors that will be found in the next section. LEAGUE ASSOCIATIONS The modern minor league system traces its roots to the formation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (NAPBL) in 1902, an umbrella organization that established league classifications and a salary structure in an agreement with Major League Baseball. The group simplified the name to “Minor League Baseball” in 1999. MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Patrick Powers, 1901 – 1909 Michael Sexton, 1910 – 1932 -

12-Weequahic Newsletter Spring

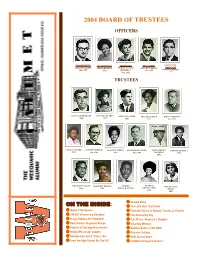

2004 BOARD OF TRUSTEES OFFICERS CO-PRESIDENT CO-PRESIDENT SECRETARY TREASURER EXECUTIVE HAROLD BRAFF JUDY BENNETT MYRNA JELLING SHELDON BROSS DIRECTOR June 1952 1972 WEISSMAN Jan. 1955 PHILIP YOURISH Jan. 1953 1964 TRUSTEES DAVID LIEBERFARB YVONNE CAUSBEY ARTHUR LUTZKE ADILAH QUDDUS BERT MANHOFF 1965 1977 1963 1971 Jan. 1938 FAITH HOWARD SAM WEINSTOCK LORAINE WHITE DAVID SCHECHNER MARY BROWN GERALD RUSSELL 1982 Jan. 1955 1964 June 1946 DAWKINS 1974 1971 CHARLES TALLEY MARJORIE BROWN Principal SHARON VIVIAN ELLIS 1966 1985 RONALD STONE PRICE-CATES SIMON 1972 1959 Newark News ON THE INSIDE: The Little Shul That Could Behind The Scenes From the Voices of Alumni, Faculty, & Friends $40,000 Scholarship Donation You Ruined My Day Hisani Dubose, NJ Filmmaker Carl Prince: Brooklyn’s Dodgers Herb Schon's Rugelach Recipe In Loving Memory Profiles of Distinguished Alumni Sheldon Belfer’s POP QUIZ Waldo Winchester Column Reunion Listings Scholarships Are A “Class” Act WHS Alumni Store From the High School On The Hill Football Fantasy Fundraiser 2004 BOARD OF TRUSTEES OFFICERS CO-PRESIDENT CO-PRESIDENT SECRETARY TREASURER EXECUTIVE HAROLD BRAFF JUDY BENNETT MYRNA JELLING SHELDON BROSS DIRECTOR June 1952 1972 WEISSMAN Jan. 1955 PHILIP YOURISH Jan. 1953 1964 TRUSTEES DAVID LIEBERFARB YVONNE CAUSBEY ARTHUR LUTZKE ADILAH QUDDUS BERT MANHOFF 1965 1977 1963 1971 Jan. 1938 FAITH HOWARD SAM WEINSTOCK LORAINE WHITE DAVID SCHECHNER MARY BROWN GERALD RUSSELL 1982 Jan. 1955 1964 June 1946 DAWKINS 1974 1971 CHARLES TALLEY MARJORIE BROWN Principal -

PDF of Apr 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr.