Faculty Government at Chapel Hill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chapel Hill Methodist Church, a Centennial History, 1853-1953

~bt <lCbaptl 1;111 1Mttbobist €burcb a ~entenntal ,tstOtP, lS53~1953 Qtbe €:bapel i;tll :Metbobigt C!Cbutcb 2l ftentennial ~i6tor!" tS53~1953 By A Committee of the Church Fletcher M. Green, Editor ~bapel ~tll 1954 Contents PREFACE Chapter THE FIRST CHURCH, 1853-1889 By Fletcher M. Green II THE SECOND CHURCH, 1885 -192 0 15 By Mrs. William Whatley Pierson III THE PRESENT CHURCH, 1915-1953 23 By Louis Round Wilson IV WOMEN'S WORK 38 By Mrs.William Whatley Pierson V RELIGIOUS ACTIVITIESOF THE TWENTIETHCENTURY ,------ 52 By Louis Round Wilson and Edgar W. Knight Appendix: LIST OF MINISTERS 65 Compiled by Fletcher M. Green PREFACE Dr. Louis Round Wilson originally suggested the idea of a centennial history of the Chapel Hill Methodist Church in a letter to the pastor, the Reverend Henry G. Ruark, on July 6, 1949. After due consideration the minister appointed a com- mittee to study the matter and to formulate plans for a history. The committee members were Mrs. Hope S. Chamberlain, Fletcher M. Green, Mrs. Guy B. Johnson, Edgar W. Knight, Mrs. Harold G. McCurdy, Mrs. Walter Patten, Mrs. William Whatley Pierson, Mrs. Marvin H. Stacy, and Dr. Louis R. Wilson, chairman. The commilttee adopted a tentative outline and apportioned the work of gathering data among its members. Later Dr. Wilson resigned as chairman and was succeeded by Fletcher M. Green. Others of the group resigned from the committee. Finally, after the data were gathered, Mrs. Pierson, Dr. Green, Dr. Knight, and Dr. Wilson were appointed to write the history. On October 11, 1953, at the centennial cele- bration service Dr. -

Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932: Subject Index

Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932: Subject Index NAME MEETING DAY VOLUME PAGENOS CITATION 03-12- Abernathy Hall E 1907 11 135 plans and bids for new infirmary 06-17- Abernathy Hall R 1919 12 155 recommends tablet to Miss Bessie Roper who lost her life while nursing 06-12- Abernathy Hall R 1923 12 464-65 additions to infirmary planned 02-06- Administration R 1795 1 162-71 laws & regulations of the university,duty of the president & students 12-21- Administration R 1793 1 126-30 report of appted committee,Stewards house,tuition,rooms, etc 11-14- Administration R 1795 1 192 Professor of Humanity referred to as Professor of Languages 07-13- Administration S 1796 1 217-18 Ker's resignation,faculty & other appointments 12-09- Administration R 1796 1 236 first use of term "principal of the University" 12-09- Administration R 1796 1 239-40 duties of the Professor of Languages & Professor of Math and of President Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina Records, 1789-1932: Subject Index 1 07-11- Administration S 1804 3 53-54 President discharging duties of Principal Professor, compensation tuition 12-15- Administration:President R 1875 7 249-56 Chair of Faculty 06-01- Administration R 1876 7 262 resolved to elect a President Administration: 06-13- President S 1876 7 266-69 elected K.P. Battle 12-19- Administration R 1833 5 253 most senior professor aids President when latter is ill-for Caldwell adm. 06-05- Administration-Pres. asst R 1895 9 452 Visiting Committee Report, reference to J.W. -

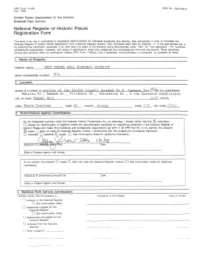

Street & Number a Nortion of the Blocks Roughl V Botmded Bv H. Cameron

NPS Form I 0-900 OMS No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990: United States Department of the Interior National Park Service This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Comolete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions. architectural classification. materials. and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter. word processor. or computer. to complete all items. historic name ____:~.,:,.!:~'"E=S=T'----""'CH= .....=A..P::....::EL=-....::.HI=LL=-=hJ:=S==-T=O=R=I"-"C::..____.:::D:...:I=S-=TR=l =-IC"""'T=----------------- other names/site number _N_/A ______________________________ _ street & number a nortion of the blocks roughlv botmded bv H. Cameron Ave l~jl~bt for publication t·'!alette St., Ransom St., Pittsboro St., University Dr., & the ~~est\vood Subdivision city or town Chapel Hill N ;_K) vicinity state North Carolina code _NC__ county ____,O""""r....,a...... n.....,_,g .....e~------ code _13_5_ zip code 2 7 51 I.J. State of Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property 0 meets 0 does not meet the National Register criteria. ( 0 See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting offic1ai!Title Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. -

JAMES PATRICK MCCARTHY, JR. Commerce and College

JAMES PATRICK MCCARTHY, JR. Commerce and College: State Higher Education and Economic Development in North Carolina and Georgia, 1850-1890 (Under the Direction of EMORY M. THOMAS) From 1850 to 1890, the Universities of Georgia and North Carolina undertook significant structural and curricular reform in an effort to hasten the economic development of their states and region. Led by trustee William Mitchell, the University of Georgia adopted a reform plan in the 1850s that was both comprehensive and far-reaching. The plan did not survive the Civil War, but Mitchell and his supporters used it as their guide in expanding the university in the 1860s, obtaining the Morrill Land Grant funds in the 1870s, and continuing to expand and diversify the university’s offerings against opposition in the 1880s. The trustees and faculty at the University of North Carolina began more modest reforms in the 1850s that survived the war. Deterred considerably by Reconstruction, Kemp Battle and the trustees grew the university’s curriculum immensely in the late 1870s and early 1880s, alongside other state institutions designed to improve the economy through education. The Watauga Club and the North Carolina Farmer’s Alliance took the Morrill Funds away from the university, but it had already taken the rough form of a modern university and consequently become a font of Southern Progressivism. The shifting educational policies and practices at these two universities between 1850 and 1890 reveal several things about these schools and Southern higher education. Substantial curricular reforms began quite early; they continued through the Civil War, Reconstruction and beyond; and they were just as diverse and comprehensive as reforms elsewhere in the nation. -

Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960

BLACK FREEDOM AND THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, 1793-1960 JOHN K. CHAPMAN A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: James L. Leloudis Jerma A. Jackson Reginald Hildebrand Gerald Horne Timothy B. Tyson ” 2006 JOHN K. CHAPMAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JOHN K. CHAPMAN: Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960 (Under the direction of James L. Leloudis) Recent histories of the University of North Carolina trivialize the institution’s support for white supremacy during slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, while denying that this unjust past affects the university today. The celebratory lens also filters out African American contributions to the university. In fact, most credit for UNC’s increased diversity is due to the struggles of African Americans and other traditionally disenfranchised groups for equal rights. During both the 1860s and the1960s, black freedom movements promoted norms of democratic citizenship and institutional responsibility that challenged the university to become more honest, more inclusive, and more just. By censoring this historical viewpoint, previous scholarship has contributed to a culture of denial and racial historical amnesia that heralds UNC as the “University of the People,” without seriously engaging questions of justice in the past or the present. This dissertation demonstrates that before 1865, the gentry used the university to promote the growth of slavery. Following Emancipation, university trustees led the white supremacy campaign to suppress black freedom and Radical Reconstruction. -

![The Hellenian [Serial]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4991/the-hellenian-serial-12614991.webp)

The Hellenian [Serial]

v^cox-cXx^o^Xv ^^c^<^^o^^^^ . i. \V^WXV\XW\X^\.VW\WV\.'V\WW i^ . -/A Xei^ :^. I ^ .>' W§^^'S'^-^ LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, Endowed by the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies. Alcove "HSKLJ^ / e ?>"|^- o^y^ li This book must not be taken from the Library building. 30)«n 39 - * U 1 r ] rti 1 1 1 1 1 fK. A flwii.N. • - i(in«>xit>iifv Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill http://www.archive.org/details/hellenianserial1890univ ®ije MHltninn: Publio^eti ^nmmlU) UV THE |'rati'rntttr0 of H)t UnwtvBtU} (.»!• Ilortti ^uvoiina. .^^loyOiafe— E. M. UZZELL, PRINTER, RALEIGH ^^^r- mttft EDITOR-IN-CHIEF : E. W. MARTIN, ./. 7'. iJ. </>. J. V. LEWIS, 0. r. J., W. W. DAVIES, Jr., A. 8., GEO. M. GRAHAM, Z. W. 2'. J. F. RHEM, B. 6. 11., JNO. D. BELLAMY, Jr., ./. A'., F. H. BATCHELOR, </>. A'. 2'. * R. H. HOLLAND, A'. ./., C. D. BENNETT, I. A'., N. A CURRIE, -. -V. BUSINESS manager: / J. F. HENDREN, J. A\ A'. Prttt(ittton* When this AnnuaP s dedicated I will truly be elated^ As my task is quite gigantic^ doii' t yoic kiioiv. For you see Pin in a pickle If yon all I do not tickle Into cachinnations^ really^ don^ t yott knoiv. Now my theme is quite ecstatic And in pressure hydrostatic^ But iV s just as sweet as ^ lasses^ donU you know. If s the girls of Carolina '^Et omnis vera regina^''^ And the ^^ Hillians^^ just adore them^ do?t' t you kno7t\ So I pen this dedication To the fairest of the nation^ To North Carolijia^ s daughters^ don'' t you knoiv. -

Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina at the Local Level

BLACK FREEDOM AND THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, 1793-1960 JOHN K. (YONNI) CHAPMAN A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: James L. Leloudis Jerma A. Jackson Reginald Hildebrand Gerald Horne Timothy B. Tyson This document has been reformatted. Page numbers do not correspond to the official University Microfilms version of the dissertation. Consult the original in the North Carolina Collection of Wilson Library or Davis Library at the University of North Carolina for citation purposes. Access electronically at http://webcat.lib.unc.edu/search?/aChapman%2C+John+K/achapman+john+k/1%2C2%2C4%2CB/frameset&FF=ac hapman+john+kenyon&2%2C%2C3 ! 2006 JOHN K. (YONNI) CHAPMAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED [email protected] ii ABSTRACT JOHN K. CHAPMAN: Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960 (Under the direction of James L. Leloudis) Recent histories of the University of North Carolina trivialize the institution’s support for white supremacy during slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, while denying that this unjust past affects the university today. The celebratory lens also filters out African American contributions to the university. In fact, most credit for UNC’s increased diversity is due to the struggles of African Americans and other traditionally disenfranchised groups for equal rights. During both the 1860s and the1960s, black freedom movements promoted norms of democratic citizenship and institutional responsibility that challenged the university to become more honest, more inclusive, and more just.