The Eskimo Curlew in Britain Tim Melling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keys to Identifying Little Curlew

MIGRATION PATTERN Keys to identifying Little Curlew Little Curlewin winterquarters at Cairns, Queensland,Australia, November 1975. Photo/Toma• Pain Gardner Not surprisingly,no ornithologisthas seen both the Little and Eskimo curlews nutus)is a speciesheld by some This new speciesFor North heauthorsLittleto Curlew be conspecific(Numenius with mi- in the field. The only detailedpublished the Eskimo Curlew (N. borealis). It America can be readily comparisonis that based by Farrand breeds in northeastern Siberia (Labutin identified in flight and (1977) on the skins of both. He conclud- and others, 1982) and winters in Austra- producesa variety of vocal ed thatthe two formsare separablein the lasia. This speciesis regardedas "rare, and instrumental sounds field under ideal conditions, and writes: little-studied and threatened," rather than "The Eskimo Curlew is a more boldly "endangered,"in the U.S.S.R. (Banni- and coarselymarked bird, with heavier kov, 1978). Brett A. Lane, the wader streakingon the sides of the face and studiescoordinator for the Royal Austra- neck, and dark chevrons on the breast and lasian Ornithologists' Union (pets. flanks;the Little Curlewhas a relatively comm., December1982), saysthe spe- Jeffery Boswail morefinely streakedface and neck, and cies "possiblynumbers many thousands the breast is streaked rather than marked (10,000+ ?)." and with chevrons,the chevronsbeing few in The Little Curlew was recently ob- number and confined to the flanks. In served for the first time in North Amer- Boris N. Veprintsev bothspecies the underwing covertsand ica. The species'closest breeding ground axillaries are barred with dark brown, but to North America is only about 1250 in the Eskimo Curlew these feathers are a mileswest of the nearestpoint of main- rich cinnamon, while in the Little Curlew land Alaska. -

OSNZ News Edited by PAUL SAGAR, 21362 Hereford Street, Christchurch, for the Members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (Inc.)

Supplement to Notornis, Vol. 25, Part 3, September 1978 OSNZ news Edited by PAUL SAGAR, 21362 Hereford Street, Christchurch, for the members of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand (Inc.). No. 8 September 1978 NOTE: Next deadline is earlier to try to beat the Christmas and January shut- Deadline for the December issue will be down of printers and have NOTORNIS 20 November. and OSNZ NEWS out early in 1979. DACHICKS Rough estimates: northland 150-200; The 1978 inquiry into the NZ Dabchick has gone remarkably well, with North Island Volcanic Plateau 600-800; South Taranakii members putting in a lot of time, often with meagre results, in order to help form an overall Wanganui 30; ManawatulWairarapa 300; picture of the status and habits of this species. GisborneiHawkes Bay 50. Total 1 150-1400. We began with a series of questions, to which we now have much better answers. If We thus already have a fairly good base members can stand it, we need another year's effort to confirm and clarify these answers. line agalnst which to measure any major changes in the future. Another year's f~eld 1. Is the NZ Dabchick extinct in the South Island? Answer, apparently yes. Was it ever work should cons~derably Improve the strong there? Possibly not (see Oliver). accuracy of our knowledge. 2. Does the North Island population reach a total of 1000? Answer, yes. Est~matedtotal Regional activity (very rough, see below) 1 1 50-1400 birds. We have no up-tb-date report from Far 3. Are Australian grebelets taking over? Answer, in North Island, not yet. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

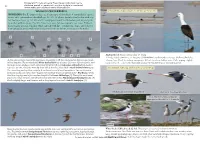

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

The All-Bird Bulletin

Advancing Integrated Bird Conservation in North America Spring 2014 Inside this issue: The All-Bird Bulletin Protecting Habitat for 4 the Buff-breasted Sandpiper in Bolivia The Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Conserving the “Jewels 6 Act (NMBCA): Thirteen Years of Hemispheric in the Crown” for Neotropical Migrants Bird Conservation Guy Foulks, Program Coordinator, Division of Bird Habitat Conservation, U.S. Fish and Bird Conservation in 8 Wildlife Service (USFWS) Costa Rica’s Agricultural Matrix In 2000, responding to alarming declines in many Neotropical migratory bird popu- Uruguayan Rice Fields 10 lations due to habitat loss and degradation, Congress passed the Neotropical Migra- as Wintering Habitat for tory Bird Conservation Act (NMBCA). The legislation created a unique funding Neotropical Shorebirds source to foster the cooperative conservation needed to sustain these species through all stages of their life cycles, which occur throughout the Western Hemi- Conserving Antigua’s 12 sphere. Since its first year of appropriations in 2002, the NMBCA has become in- Most Critical Bird strumental to migratory bird conservation Habitat in the Americas. Neotropical Migratory 14 Bird Conservation in the The mission of the North American Bird Heart of South America Conservation Initiative is to ensure that populations and habitats of North Ameri- Aros/Yaqui River Habi- 16 ca's birds are protected, restored, and en- tat Conservation hanced through coordinated efforts at in- ternational, national, regional, and local Strategic Conservation 18 levels, guided by sound science and effec- in the Appalachians of tive management. The NMBCA’s mission Southern Quebec is to achieve just this for over 380 Neo- tropical migratory bird species by provid- ...and more! Cerulean Warbler, a Neotropical migrant, is a ing conservation support within and be- USFWS Bird of Conservation Concern and listed as yond North America—to Latin America Vulnerable on the International Union for Conser- Coordination and editorial vation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Ecological Landscape Analysis of Clare Ecodistrict 730 40

Ecological Landscape Analysis of Clare Ecodistrict 730 40 © Crown Copyright, Province of Nova Scotia, 2014. Ecological Landscape Analysis, Ecodistrict 730: Clare Prepared by the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources Authors: Western Region DNR staff ISBN 978-1-55457-598-5 This report, one of 38 for the province, provides descriptions, maps, analysis, photos and resources of the Clare Ecodistrict that can help landowners and planners understand important characteristics of the landscape. The report details the main elements in the ecodistrict and, of particular interest to woodland owners, vegetation types within forest stands. Ecological Landscape Analysis (ELA) is a first step in developing an ecosystem approach to managing resource values at a landscape level. It supports planning by landowners wanting to understand how their land fits into the landscape ecosystem. Additional direction will be provided by a landscape planning guide, and internet-based inventory update system, both of which are currently under development. The ELAs were analyzed and written from 2005 – 2009. They provide baseline information for this period in a standardized framework of ecosystem mapping and data summary designed to support future data updates, forecasts and trends. This document includes Part 1 – Learning about what makes this ecodistrict distinctive – and Part 2 – How woodland owners can apply landscape concepts to their woodland. Part 3 – Greater detail for forest planners and analysts – will be available on request by contacting DNR officials -

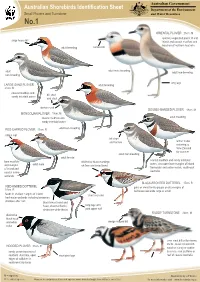

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

Nocturnal Roost on South Carolina Coast Supports Nearly Half of Atlantic Coast Population of Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius Hudsonicus During Northward Migration

research paper Wader Study 128(2): xxx–xxx. doi:10.18194/ws.00228 Nocturnal roost on South Carolina coast supports nearly half of Atlantic coast population of Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus during northward migration Felicia J. Sanders1, Maina C. Handmaker2, Andrew S. Johnson3 & Nathan R. Senner2 1South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, 220 Santee Gun Club Road, McClellanville, SC 29458, USA. [email protected] 2Dept. of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, 715 Sumter Street, Columbia, SC 29208, USA 3Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, New York 14850, USA Sanders, F.J., M.C. Handmaker, A.S. Johnson & N.R. Senner. Nocturnal roost on South Carolina coast supports nearly half of Atlantic coast population of Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus during northward migration. Wader Study 128(2): xxx–xxx. Hudsonian Whimbrel Numenius hudsonicus are rapidly declining and understanding Keywords their use of migratory staging sites is a top research priority. Nocturnal roosts are site fidelity an essential, yet often overlooked component of staging sites due to their apparent rarity, inaccessibility, and inconspicuousness. The coast of Georgia and stopover South Carolina is one of two known important staging areas for Atlantic coast staging area Whimbrel during spring migration. Within this critical staging area, we discovered the largest known Whimbrel nocturnal roost in the Western Hemisphere at population estimate Deveaux Bank, South Carolina. Surveys in 2019 and 2020 during peak spring management migration revealed that Deveaux Bank supports at least 19,485 roosting Whimbrel, conservation which represents approximately 49% of the estimated eastern population of Whimbrel and 24% of the entire North American population. -

TESTING a MODEL THAT PREDICTS FUTURE BIRD LIST TOTALS by Robert W. Ricci Introduction One of the More Enjoyable Features of Bird

TESTING A MODEL THAT PREDICTS FUTURE BIRD LIST TOTALS by Robert W. Ricci Introduction One of the more enjoyable features of birding as a hobby is in keeping bird lists. Certainly getting into the habit of carefully recording our own personal birding experiences paves the way to a better understanding of the birds around us and prepares our minds for that chance encounter with a vagrant. In addition to our own field experiences, we advance our understanding of bird life through our reading and fraternization with other birders. One of the most useful ways we can communicate is by sharing our bird lists in Christmas Bird Counts (CBC), breeding bird surveys, and in the monthly compilation of field records as found, for example, in this journal. As important as our personal observation might be, however, it is only in the analysis of the cumulative experiences of many birders that trends emerge that can provide the substance to answer important questions such as the causes of vagrancy in birds (Veit 1989), changes in bird populations (Davis 1991), and bird migration patterns (Roberts 1995). Most birders, at one time or another, have speculated about what new avian milestones they will overtake in the future. For example, an article in this journal (Forster 1990) recorded the predictions of several birding gurus on which birds might be likely candidates as the next vagrants to add to the Massachusetts Avian Records Committee roster of 451 birds. Just as important as predictions of which birds might appear during your field activities are predictions of the total number of birds that you might expect to encounter. -

In the Cape Verde Islands

ZOOLOGIA CABOVERDIANA REVISTA DA SOCIEDADE CABOVERDIANA DE ZOOLOGIA VOLUME 5 | NÚMERO 1 Abril de 2014 ZOOLOGIA CABOVERDIANA REVISTA DA SOCIEDADE CABOVERDIANA DE ZOOLOGIA Zoologia Caboverdiana is a peer-reviewed open-access journal that publishes original research articles as well as review articles and short notes in all areas of zoology and paleontology of the Cape Verde Islands. Articles may be written in English (with Portuguese summary) or Portuguese (with English summary). Zoologia Caboverdiana is published biannually, with issues in spring and autumn. For further information, contact the Editor. Instructions for authors can be downloaded at www.scvz.org Zoologia Caboverdiana é uma revista científica com arbitragem científica (peer-review) e de acesso livre. Nela são publicados artigos de investigação original, artigos de síntese e notas breves sobre zoologia e paleontologia das Ilhas de Cabo Verde. Os artigos podem ser submetidos em inglês (com um resumo em português) ou em português (com um resumo em inglês). Zoologia Caboverdiana tem periodicidade bianual, com edições na primavera e no outono. Para mais informações, deve contactar o Editor. Normas para os autores podem ser obtidas em www.scvz.org Chief Editor | Editor principal Dr Cornelis J. Hazevoet (Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Portugal); [email protected] Editorial Board | Conselho editorial Dr Joana Alves (Instituto Nacional de Saúde Pública, Praia, Cape Verde) Prof. Dr G.J. Boekschoten (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Dr Eduardo Ferreira (Universidade de Aveiro, Portugal) Rui M. Freitas (Universidade de Cabo Verde, Mindelo, Cape Verde) Dr Javier Juste (Estación Biológica de Doñana, Spain) Evandro Lopes (Universidade de Cabo Verde, Mindelo, Cape Verde) Dr Adolfo Marco (Estación Biológica de Doñana, Spain) Prof. -

The Potential Breeding Range of Slender-Billed Curlew Numenius Tenuirostris Identified from Stable-Isotope Analysis

Bird Conservation International (2016) 0 : 1 – 10 . © BirdLife International, 2016 doi:10.1017/S0959270916000551 The potential breeding range of Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris identified from stable-isotope analysis GRAEME M. BUCHANAN , ALEXANDER L. BOND , NICOLA J. CROCKFORD , JOHANNES KAMP , JAMES W. PEARCE-HIGGINS and GEOFF M. HILTON Summary The breeding areas of the Critically Endangered Slender-billed Curlew Numenius tenuirostris are all but unknown, with the only well-substantiated breeding records being from the Omsk prov- ince, western Siberia. The identification of any remaining breeding population is of the highest priority for the conservation of any remnant population. If it is extinct, the reliable identification of former breeding sites may help determine the causes of the species’ decline, in order to learn wider conservation lessons. We used stable isotope values in feather samples from juvenile Slender-billed Curlews to identify potential breeding areas. Modelled precipitation δ 2 H data were compared to feather samples of surrogate species from within the potential breeding range, to produce a calibration equation. Application of this calibration to samples from 35 Slender-billed Curlew museum skins suggested they could have originated from the steppes of northern Kazakhstan and part of southern Russia between 48°N and 56°N. The core of this area was around 50°N, some way to the south of the confirmed nesting sites in the forest steppes. Surveys for the species might be better targeted at the Kazakh steppes, rather than around the historically recog- nised nest sites of southern Russia which might have been atypical for the species. We consider whether agricultural expansion in this area may have contributed to declines of the Slender-billed Curlew population. -

SIS) – 2017 Version

Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites Information Sheet on EAA Flyway Network Sites (SIS) – 2017 version Available for download from http://www.eaaflyway.net/about/the-flyway/flyway-site-network/ Categories approved by Second Meeting of the Partners of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership in Beijing, China 13-14 November 2007 - Report (Minutes) Agenda Item 3.13 Notes for compilers: 1. The management body intending to nominate a site for inclusion in the East Asian - Australasian Flyway Site Network is requested to complete a Site Information Sheet. The Site Information Sheet will provide the basic information of the site and detail how the site meets the criteria for inclusion in the Flyway Site Network. When there is a new nomination or an SIS update, the following sections with an asterisk (*), from Questions 1-14 and Question 30, must be filled or updated at least so that it can justify the international importance of the habitat for migratory waterbirds. 2. The Site Information Sheet is based on the Ramsar Information Sheet. If the site proposed for the Flyway Site Network is an existing Ramsar site then the documentation process can be simplified. 3. Once completed, the Site Information Sheet (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Flyway Partnership Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the Information Sheet and, where possible, digital versions (e.g. shapefile) of all maps. -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------