Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enzymes Handling/Processing

Enzymes Handling/Processing 1 Identification of Petitioned Substance 2 3 This Technical Report addresses enzymes used in used in food processing (handling), which are 4 traditionally derived from various biological sources that include microorganisms (i.e., fungi and 5 bacteria), plants, and animals. Approximately 19 enzyme types are used in organic food processing, from 6 at least 72 different sources (e.g., strains of bacteria) (ETA, 2004). In this Technical Report, information is 7 provided about animal, microbial, and plant-derived enzymes generally, and more detailed information 8 is presented for at least one model enzyme in each group. 9 10 Enzymes Derived from Animal Sources: 11 Commonly used animal-derived enzymes include animal lipase, bovine liver catalase, egg white 12 lysozyme, pancreatin, pepsin, rennet, and trypsin. The model enzyme is rennet. Additional details are 13 also provided for egg white lysozyme. 14 15 Chemical Name: Trade Name: 16 Rennet (animal-derived) Rennet 17 18 Other Names: CAS Number: 19 Bovine rennet 9001-98-3 20 Rennin 25 21 Chymosin 26 Other Codes: 22 Prorennin 27 Enzyme Commission number: 3.4.23.4 23 Rennase 28 24 29 30 31 Chemical Name: CAS Number: 32 Peptidoglycan N-acetylmuramoylhydrolase 9001-63-2 33 34 Other Name: Other Codes: 35 Muramidase Enzyme Commission number: 3.2.1.17 36 37 Trade Name: 38 Egg white lysozyme 39 40 Enzymes Derived from Plant Sources: 41 Commonly used plant-derived enzymes include bromelain, papain, chinitase, plant-derived phytases, and 42 ficin. The model enzyme is bromelain. -

Table S4. List of Enzymes Directly Involved in the Anti-Oxidant Defense Response

Table S4. List of Enzymes directly involved in the anti-oxidant defense response. Gene Name Gene Symbol Classification/Pathway 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase 6PGD NADPH regeneration/Pentose Phosphate Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase G6PD NADPH regeneration/Pentose Phosphate Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 IDH1 NADPH regeneration/Krebs Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 2 IDH2 NADPH regeneration/Krebs Malic Enzyme 1 ME1 NADPH regeneration/Krebs Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 1 MTHFD1 NADPH regeneration/Folate Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 MTHFD2 NADPH regeneration/Folate Nicotinamide Nucleotide Transhydrogenase NNT NADPH regeneration/NAD Catalase CAT Antioxidants/Catalses/free radical detoxification Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit GCLC Antioxidants/Glutathione synthesis Glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit GCLM Antioxidants/Glutathione synthesis Glutathione peroxidase1 GPx1 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione peroxidase2 GPx2 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione peroxidase3 GPx3 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione peroxidase4 GPx4 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione peroxidase5 GPx5 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione peroxidase6 GPx6 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione peroxidase7 GPx7 Antioxidants/Glutathione Peroxidases/free radical detoxification Glutathione S-transferase -

Current IUBMB Recommendations on Enzyme Nomenclature and Kinetics$

Perspectives in Science (2014) 1,74–87 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/pisc REVIEW Current IUBMB recommendations on enzyme nomenclature and kinetics$ Athel Cornish-Bowden CNRS-BIP, 31 chemin Joseph-Aiguier, B.P. 71, 13402 Marseille Cedex 20, France Received 9 July 2013; accepted 6 November 2013; Available online 27 March 2014 KEYWORDS Abstract Enzyme kinetics; The International Union of Biochemistry (IUB, now IUBMB) prepared recommendations for Rate of reaction; describing the kinetic behaviour of enzymes in 1981. Despite the more than 30 years that have Enzyme passed since these have not subsequently been revised, though in various respects they do not nomenclature; adequately cover current needs. The IUBMB is also responsible for recommendations on the Enzyme classification naming and classification of enzymes. In contrast to the case of kinetics, these recommenda- tions are kept continuously up to date. & 2014 The Author. Published by Elsevier GmbH. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). Contents Introduction...................................................................75 Kinetics introduction...........................................................75 Introduction to enzyme nomenclature ................................................76 Basic definitions ................................................................76 Rates of consumption and formation .................................................76 Rate of reaction .............................................................76 -

Fluoride Is a Strong and Specific Inhibitor of (~~Y~~E~R~C~~ Ap,A Hydrolases

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Volume 262, number 2, 205-208 FEBS 08241 March 1990 Fluoride is a strong and specific inhibitor of (~~y~~e~r~c~~ Ap,A hydrolases Andrzej Guranowski Katedra Biackemii, Ak~mia Rolnicza, ul. Wdyirska 35, PL-60-637 Poznati, Pala~d Received 24 November 1989; revised version received 19 January 1990 Fluoride acts as a noncompetitive, strong inhibitor of (usyrmnetricnf) Ap,A hydrolases (EC 361.17). The K, values estimated for the enzymes isolat- ed from seeds of some higher plants (yellow lupin, sunflower and marrow) are in the range of 2-3 pM and Is, for the hydrolase from a mammalian tissue (beef liver) is 20 BM. The anion, up to 25 mM, does not affect the following other enzymes which are able to degrade the bias’-n~l~sidyl~ oligophospha~s: Escherichiu coli (sym~tr~~ AphA hydrolase (EC 3.6.1.41), yeast Ap,A phosphorylsse (EC 2.7.7.53), yellow lupin Ap,A hydrol- ase (EC 3.6.1.29) and phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.1). None of halogenic anions but fluoride affects the activity of (asynrmefricnf) Ap,A hydrolases. Usefulness of the fluoride effect for the in vivo studies on the Ap,A metabolism is shortly discussed. Fluoride; Enzyme inhibition; Ap,A hydrolase 1. INTRODUCTION of the dinucleotides catalyzed by lysyl-, phenylalanyl-, and alanyl-tRNA synthetases [2-51 and inhibits the rat Cellular levels of bis(5 ’ -nucleosidyl)oligophosphates [24] and lupin [l l] Ap3A hydrolases as well as the rat such as Ap.+A, Ap3A or Ap4G are probably modulated liver ApdA hydrolase f25]. -

Collection of Information on Enzymes a Great Deal of Additional Information on the European Union Is Available on the Internet

European Commission Collection of information on enzymes A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2002 ISBN 92-894-4218-2 © European Communities, 2002 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Final Report „Collection of Information on Enzymes“ Contract No B4-3040/2000/278245/MAR/E2 in co-operation between the Federal Environment Agency Austria Spittelauer Lände 5, A-1090 Vienna, http://www.ubavie.gv.at and the Inter-University Research Center for Technology, Work and Culture (IFF/IFZ) Schlögelgasse 2, A-8010 Graz, http://www.ifz.tu-graz.ac.at PROJECT TEAM (VIENNA / GRAZ) Werner Aberer c Maria Hahn a Manfred Klade b Uli Seebacher b Armin Spök (Co-ordinator Graz) b Karoline Wallner a Helmut Witzani (Co-ordinator Vienna) a a Austrian Federal Environmental Agency (UBA), Vienna b Inter-University Research Center for Technology, Work, and Culture - IFF/IFZ, Graz c University of Graz, Department of Dermatology, Division of Environmental Dermatology, Graz Executive Summary 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Technical Aspects of Enzymes (Chapter 3) Application of enzymes (Section 3.2) Enzymes are applied in various areas of application, the most important ones are technical use, manufacturing of food and feedstuff, cosmetics, medicinal products and as tools for re- search and development. Enzymatic processes - usually carried out under mild conditions - are often replacing steps in traditional chemical processes which were carried out under harsh industrial environments (temperature, pressures, pH, chemicals). Technical enzymes are applied in detergents, for pulp and paper applications, in textile manufacturing, leather industry, for fuel production and for the production of pharmaceuticals and chiral substances in the chemical industry. -

Characterisation, Classification and Conformational Variability Of

Characterisation, Classification and Conformational Variability of Organic Enzyme Cofactors Julia D. Fischer European Bioinformatics Institute Clare Hall College University of Cambridge A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 11 April 2011 This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. This dissertation does not exceed the word limit of 60,000 words. Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the members of the Thornton research group for their constant interest in my work, their continuous willingness to answer my academic questions, and for their company during my time at the EBI. This includes Saumya Kumar, Sergio Martinez Cuesta, Matthias Ziehm, Dr. Daniela Wieser, Dr. Xun Li, Dr. Irene Pa- patheodorou, Dr. Pedro Ballester, Dr. Abdullah Kahraman, Dr. Rafael Najmanovich, Dr. Tjaart de Beer, Dr. Syed Asad Rahman, Dr. Nicholas Furnham, Dr. Roman Laskowski and Dr. Gemma Holli- day. Special thanks to Asad for allowing me to use early development versions of his SMSD software and for help and advice with the KEGG API installation, to Roman for knowing where to find all kinds of data, to Dani for help with R scripts, to Nick for letting me use his E.C. tree program, to Tjaart for python advice and especially to Gemma for her constant advice and feedback on my work in all aspects, in particular the chemistry side. Most importantly, I would like to thank Prof. Janet Thornton for giving me the chance to work on this project, for all the time she spent in meetings with me and reading my work, for sharing her seemingly limitless knowledge and enthusiasm about the fascinating world of enzymes, and for being such an experienced and motivational advisor. -

The Genetic Significance of Enzymes in Tissues

THE GENETIC SIGNIFICANCE OF ENZYMES IN TISSUES. by PEGGY CLARK, Master of Science, (Sydney). Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philos ophy in the University of New South Wales. Submitted. lAtyr. , 1970 KENSINGTON E/a ADDITIONAL WORK UNDERTAKEN IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILO SOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF HUMAN GENETICS, UNIVERS ITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES. "ABO, Rh and MNS Blood Typing Results and other Biochemical Traits in the People of the Yap Islands"., Jane Hainline, Peggy Clark and R.J. Walsh, published in Arch eology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 4, 1969, pp. 64 - 71. "A Genetic Study of the Maring People of the Simbai Valley, Bismarck Mountains, New Guinea", in conjunction with Georgeda Bick, Columbia University - in preparation. TABLE OF CONTENTS. A Page No. List of illustrations. i-v. Summary 1,2. Chapter 1, General Introduction. 3-32. 1.1.1. Historical survey of genetics. 3* 2. Beginnings of modern genetics. 3»4. 3. Complementary contributions of breeding experiments and cytology. 5* 4. Contributions of human studies to genetics. 6,7* 5. Structure of DNA and the development of modern genetics. 7*8. 6. Enzymes as.genetic markers and the introduction of the isozyme concept. 8-11. 1.2.1. Suitability of enzymes for the study of the evolution of proteins - primitive nature of enzymes. 11-13* 2. Epigenetic factors in the expression of enzyme phenotypes. 13*14. 3* Relationship between electrophoretic enzyme patterns and the functions of isozymes in the cell. 14-16. -

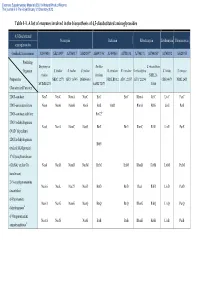

Table 1-1. a List of Enzymes Involved in the Biosynthesis of 4,5-Disubstituted Aminoglycosides

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Natural Product Reports This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 Table 1-1. A list of enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of 4,5-disubstituted aminoglycosides 4,5-Disubstituted Neomycin Butirosin Ribostamycin Lividomycin Paromomycin aminoglycosides GenBank Accession no. AJ843080 AB211959 AJ786317 AJ629247a AB097196a AJ494863 AJ781030 AJ748131 AJ744850a AJ748832 AJ628955 Producing Streptomyces Bacillus S. ribosidificus Organism S. fradiae S. fradiae S. fradiae B. circulans B. circulans S. ribosidificus S. lividus S. rimosus fradiae circulans NRRL B- Proposed or NBRC 12773 ATCC 10745 DSM 40063 NRRL B3312 ATCC 21557 ATCC 21294 CBS 844.73 NRRL 2455 MCIMB 8233 SANK 72073 11466 Characterized Function 2DOI-synthase Neo7 NeoC NemA NeoC BtrC BtrC RbmA RibC LivC ParC 2DOI-aminotransferase Neo6 NeoB NemB NeoS BtrS BtrR RbmB RibS LivS ParS 2DOI-synthase stabilizer BtrC2b 2DOIA-dehydrogenase Neo5 NeoA NemC NeoE BtrE BtrE RbmC RibE LivE ParE (NAD+ dependent) 2DOIA-dehydrogenase BtrN (radical SAM protein) 1st Glycosyltransferase (GlcNAc and/or Glc Neo8 NeoD NemD NeoM BtrM BtrM RbmD RibM LivM ParM transferase) 2′-N-acetylparomamine Neo16 NeoL Nac25 NeoD BtrD BtrD RacJ RibD LivD ParD deacetylasec 6′-Paromamine Neo11 NeoG NemG NeoQ BtrQ BtrQ RbmG RibQ LivQ ParQ dehydrogenased 6′-Oxoparomamine Neo18 NeoN NeoB BtrB BtrB RbmH RibB LivB ParB aminotransferased Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Natural Product Reports This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2013 Proposed or Neomycin -

Jessaniniessen2005.Pdf

ARTICLES A streamlined platform for high-content functional proteomics of primary human specimens methods Nadim Jessani1,4,5, Sherry Niessen1,5, BinQing Q Wei1,5, Monica Nicolau2, Mark Humphrey1, Youngran Ji2, Wonshik Han3, Dong-Young Noh3, John R Yates III1, Stefanie S Jeffrey2 & Benjamin F Cravatt1 .com/nature e Achieving information content of satisfactory breadth and depth resolution, facilitating the identification of low-abundance proteins remains a formidable challenge for proteomics. This problem is in complex samples8,9. These techniques, however, are time- .natur w particularly relevant to the study of primary human specimens, consuming (many hours per sample), difficult to perform in such as tumor biopsies, which are heterogeneous and of finite parallel and require large quantities of proteome (B1mgor quantity. Here we present a functional proteomics strategy that greater) for optimal analysis. Alternative proteomic approaches unites the activity-based protein profiling and multidimensional http://ww have emerged that have greater throughput (matrix-assisted laser protein identification technologies (ABPP-MudPIT) for the desorption ionization (MALDI) imaging6 and surface-enhanced 7 oup streamlined analysis of human samples. This convergent laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (SELDI-TOF) spectro- r G platform involves a rapid initial phase, in which enzyme activity metry), albeit at the expense of sensitivity. Furthermore, each of signatures are generated for functional classification of samples, these methods, by focusing on measurements of protein expression, followed by in-depth analysis of representative members from provides only an indirect readout of protein activity, which is lishing each class. Using this two-tiered approach, we identified more regulated by a myriad of post-translational events in vivo10. -

Enzyme Nomenclature (

Enzyme Classification Introductory article Article Contents and Nomenclature • Introduction • General Classification Structure Andrew G McDonald, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland • Notes on Chemical Nomenclature Sinead Boyce, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland • Enzyme Classes and Definitions Keith F Tipton, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland • Finding Information in ExplorEnz • Limitations and Problems Based in part on the previous versions of this eLS article ‘Enzyme • Information and Updates Classification and Nomenclature’ (2001, 2005). Online posting date: 15th April 2015 The variety of different names that had been used different enzymes with similar names, or the same enzyme under for the same enzyme and the fact that some dif- different names. ferent enzymes were known by the same name In trying to bring some order to the chaotic situation of enzyme necessitated the development of a rational sys- nomenclature, Dixon and Webb (1958) took a step that was radi- tem for their classification and nomenclature. cally different from that used in other branches of nomenclature by classifying enzymes in terms of the reactions they catalysed, The International Union of Biochemistry devised rather than by their structures. This system has been adopted a system of classification that allows the unam- and developed by the International Union of Biochemistry and biguous identification of enzymes in terms of the Molecular Biology (IUBMB), through its Joint Commission on reactions they catalyse. This relies on a numeri- Biochemical Nomenclature in association with the International cal system (the EC number) to class enzymes in Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) into the Enzyme groups according to the types of reaction catalysed Nomenclature list of enzymes classified by the reactions they and systematic naming that describes the chem- catalyse (the Enzyme List). -

Application of Enzymes in Brewing

Review Article Published: 26 Jan, 2018 Journal of Nutrition and Food Science Forecast Application of Enzymes in Brewing Ahmed M. Gomaa* Alabama Agriculture and Mechanics, USA Abstract Brewing is one of the oldest food processes done by mankind. The technology of beer production took place six thousand years ago and has been done by the world’s oldest civilizations such as the ancient Egyptians and Mesopotamians. Nowadays, brewing is one of the lead food industries in the world in general and especially the west. Enzymes utilization is one of the main pillars of brewing industry, and weather the enzyme is endogenous in the kernel itself or been added from external sources, a deep understanding and research of those enzymes is mandatory for the sake of better production and higher quality. The aim of this review is to explain the flow process of brewing and to discuss different enzymes used in brewery industry with the description of their mechanism of action. Keywords: Brewing; Enzymes; Hydrolysis Introduction Enzymes are vital biochemical materials that have been proven to be not only critical for living organisms but also in the field of food science and technology. Enzymes are participating in many important reactions in human body such as signal transduction, cell regulation, generating movement, digestion, absorption, and metabolism [1]. Enzymes are mainly tertiary structured globular proteins and their primary structure is made up of up to thousands amino acids (Figure 1), which are linked together via peptide bonds in a linear chain [2]. In addition to their physiological characteristics, enzymes play a vital role in food industry. -

4.2 Cytochrome C Oxidase

Structural and functional characterization of cytochrome c oxidase, cytochrome bc1 complex and heme A synthase from Aquifex aeolicus Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften vorgelegt beim Fachbereich 14 Biochemie, Chemie und Pharmazie der Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität in Frankfurt am Main, Deutschland von Hui ZENG aus Hubei, China Frankfurt am Main (2019) (D30) vom Fachbereich Biochemie, Chemie und Pharmazie der Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität als Dissertation angenommen. Dekan: Prof. Dr. Clemens Glaubitz 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Klaas Martinus Pos 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Hartmut Michel Datum der Disputation: Die Doktorarbeit wurde vom Dezember 2014 bis zum Dezember 2019 unter Leitung von Prof. Dr. Hartmut Michel in der Abteilung für Molekulare Membranbiologie am Max-Planck-Institut für Biophysik in Frankfurt am Main durchgeführt. Eidesstattliche Erklärung Hiermit versichere ich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig angefertigt habe und keine weiteren Hilfsmittel und Quellen als die hier aufgeführten verwendet habe. Hui ZENG Frankfurt am Main, den TO MY BELOVED FAMILY Publications 1. Guoliang Zhu*, Hui Zeng*, Shuangbo Zhang*, Jana Juli, Xiaoyun Pang, Jan Hofmann,Yan Zhang, Nina Morgner, Yun Zhu, Guohong Peng, Hartmut Michel, Fei Sun. 3.3 Å structure of hyperthermophilic respiratory complex III from Aquifex aeolicus reveals the mechanism of its thermal stability. (*: contributed equally. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. doi:10.1002/anie.201911554) 2. Hui Zeng, Guoliang Zhu, Shuangbo Zhang, Janosch Martin, Nina Morgner, Fei Sun, Guohong Peng, Hao Xie and Hartmut Michel. The isolated intact heme A synthase from Aquifex aeolicus is a trimer. (mbio, in revision) Table of contents Table of contents List of figures ............................................................................................................... III List of tables .................................................................................................................