Studies in Language Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining

Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe © Council of Europe, April 2011 The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. All correspondence concerning this publication or the reproduction or translation of all or part of the document should be addressed to the Director of Education and Languages of the Council of Europe (Language Policy Division) (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). The reproduction of extracts is authorised, except for commercial purposes, on condition that the source is quoted. Manual for Language Test Development and Examining For use with the CEFR Produced by ALTE on behalf of the Language Policy Division, Council of Europe Language Policy Division Council of Europe (Strasbourg) www.coe.int/lang Contents Foreword 5 3.4.2 Piloting, pretesting and trialling 30 Introduction 6 3.4.3 Review of items 31 1 Fundamental considerations 10 3.5 Constructing tests 32 1.1 How to define language proficiency 10 3.6 Key questions 32 1.1.1 Models of language use and competence 10 3.7 Further reading 33 1.1.2 The CEFR model of language use 10 4 Delivering tests 34 1.1.3 Operationalising the model 12 4.1 Aims of delivering tests 34 1.1.4 The Common Reference Levels of the CEFR 12 4.2 The process of delivering tests 34 1.2 Validity 14 4.2.1 Arranging venues 34 1.2.1 What is validity? 14 4.2.2 Registering test takers 35 1.2.2 Validity -

Does Washback Exist?

DOCUMENT RESUME FL 020 178 ED 345 513 AUTHOR Alderson, J. Charles; Wall,Dianne TITLE Does Washback Exist? PUB DATE Feb 92 Symposium on the NOTE 23p.; Paper presented at a Educational and Social Impactsof Language Tests, Language Testing ResearchColloquium (February 1992). For a related document, seeFL 020 177. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility(142) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Classroom Techniques;Educational Environment; Educational Research; EducationalTheories; Foreign Countries; Language Research;*Language Tests; *Learning Processes; LiteratureReviewa; Research Needs; Second LanguageInstruction; *Second Languages; *Testing the Test; Turkey IDENTIFIERS Nepal; Netherlands; *Teaching to ABSTRACT The concept of washback, orbackwash, defined as the influence of testing oninstruction, is discussed withrelation to second second language teaching andtesting. While the literature of be language testing suggests thattests are commonly considered to powerful determiners of whathappens in the classroom, Lheconcept of washback is not well defined.The first part of the discussion focuses on the concept, includingseveral different interpretations of the phenomenon. It isfound to be a far more complextopic than suggested by the basic washbackhypothesis, which is alsodiscussed and outlined. The literature oneducation in general is thenreviewed for additional information on theissues involved. Very little several research was found that directlyrelated to the subject, but studies are highlighted.Following this, empirical research on language testing is consulted forfurther insight. Studies in Turkey, the Netherlands, and Nepal arediscussed. Finally, areas for additional research are proposed,including further definition of washback, motivation and performance,the role of educational explanatory setting, research methodology,learner perceptions, and factors. A 39-item bibliography isappended. -

Assessing L2 Academic Speaking Ability: the Need for a Scenario-Based Assessment Approach

Teachers College, Columbia University Working Papers in Applied Linguistics & TESOL, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 36-40 The Forum Assessing L2 Academic Speaking Ability: The Need for a Scenario-based Assessment Approach Yuna Seong Teachers College, Columbia University In second language (L2) testing literature, from the skills-and-elements approach to the more recent models of communicative language ability, the conceptualization of L2 proficiency has evolved and broadened over the past few decades (Purpura, 2016). Consequently, the notion of L2 speaking ability has also gone through change, which has influenced L2 testers to constantly reevaluate what needs to be assessed and how L2 speaking assessment can adopt different designs and techniques accordingly. The earliest views on speaking ability date back to Lado (1961) and Carroll (1961), who took a skills-and-elements approach and defined language ability in terms of a set of separate language elements (e.g., pronunciation, grammatical structure, lexicon), which are integrated in the skills of reading, writing, listening, and speaking. According to their views, speaking ability could be assessed by test items or tasks that target and measure different language elements discretely to make inferences on one’s speaking ability. On the other hand, Clark (1975) and Jones (1985) put emphasis on communicative effectiveness and the role of performance. Clark (1975) defined speaking ability as one’s “ability to communicate accurately and effectively in real-life language-use contexts” (p. 23), and this approach encouraged the use of performance tasks that replicate real-life situations. However, the most dominant approach to viewing L2 speaking ability and its assessment has been influenced by the models of communicative competence (Canale, 1983; Canale & Swain, 1980) and communicative language ability (Bachman, 1990; Bachman & Palmer, 1996), which brought forth a multicomponential approach to understanding speaking ability in terms of various underlying and interrelated knowledge and competencies. -

Call for Proposals: Language Testing Special Issue 2021

February 28, 2019 Call for Proposals: Language Testing Special Issue 2021 The editors of Language Testing invite proposals from prospective guest editors for the 2021 special issue of the journal. Each year Language Testing devotes a special issue to papers focused on an area of current importance in the field. Guest editors are responsible for overseeing the solicitation, review, editing, and selection of articles for their special issue. Upcoming and past special issue topics have included the following: 2020: Repeated Test Taking and Longitudinal Test Score Analysis, edited by Anthony Green and Alistair Van Moere 2018: Interactional Competence, edited by India Plough, Jayanti Banerjee and Noriko Iwashita 2017: Corpus Linguistics and Language Testing, edited by Sara Cushing 2016: Exploring the Limits of Authenticity in LSP testing: The Case of a Specific-Purpose Language Tests for Health Professionals, edited by Cathie Elder 2015: The Future of Diagnostic Language Assessment, edited by Yon Won Lee 2014: Assessing Oral and Written L2 Performance: Raters’ Decisions, Rating Procedures and Rating Scales, edited by Folkert Kuiken and Ineke Vedder 2013: Language Assessment Literacy, edited by Ofra Inbar-Lourie 2011: Standards-Based Assessment in the United States, edited by Craig Deville and Micheline Chalhoub-Deville 2010: Automated Scoring and Feedback Systems for Language Assessment and Learning, edited by Xiaoming Xi The Language Testing editors will be happy to consider proposals on any coherent theme pertaining to language testing and -

British Council, London (England). English Language *Communicative Competence

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 258 440 FL 014 475 AUTHOR Alderson, J. Charles, 54.; Hughes, Arthur, Ed. TITLE Issues in Language Testing. ELT Documents 111. INSTITUTION British Council, London (England). English Language and Literature Div. REPORT NO ISBN-0-901618-51-9 PUB DATE 81 NOTE 211p, PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Communicative Competence (Languages); Conference Proceedings; *English (Second Language); *English for Special Purposes; *Language Proficiency; *Language Tests; Second Language Instruction; Test Validity ABSTRACT A symposium focusing on problems in the assessment of foreign or second language learning brought seven applied linguists together to discuss three areas of debate: communicative language testing, testing of English for specific purposes, and general language proficiency assessment. In each of these areas, the participants reviewed selected papers on the topic, reacted to them on paper, and discussed them as a group. The collected papers, reactions, and discussion reports on communicative language testing include the following: "Communicative Language Testing: Revolution or Evolution" (Keith Morrow) ancl responses by Cyril J. Weir, Alan Moller, and J. Charles Alderson. The next section, 9n testing of English for specific purposes, includes: "Specifications for an English Language Testing Service" (Brendan J. Carroll) and responses by Caroline M. Clapham, Clive Criper, and Ian Seaton. The final section, on general language proficiency, includes: "Basic Concerns /Al Test Validation" (Adrian S. Palmer and Lyle F. Bachman) and "Why Are We Interested in General Language Proficiency'?" (Helmut J. Vollmer), reactions of Arthur Hughes and Alan Davies, and the `subsequent response of Helmut J. Vollmer. -

A Pattern Language for Teaching in a Foreign Language - Part 2

A Pattern Language for Teaching in a Foreign Language - Part 2 Christian K¨oppe and Mari¨elle Nijsten Hogeschool Utrecht, Institute for Information & Communication Technology, Postbus 182, 3500 AD Utrecht, Netherlands {christian.koppe,marielle.nijsten}@hu.nl http://www.hu.nl Abstract. Teaching a technical subject in a foreign language is not just switching to the foreign language. There are specific problems related to the integration of content and learn- ing. This paper is part of ongoing work with mining of patterns which address these problems and intends to offer practical help to teachers by working towards a pattern language for technical instructors who teach students in a second language, and who are not trained in language pedagogy. This is the pre-conference version for the PLoP'12 conference. Note to workshop participants: for the PLoP 2012 conference we would like to focus on following patterns: Content-Compatible Language, Commented Action, and Language Monitor. We also would like to work on the list of related educational patterns. However, feedback on the other patterns is more than welcome, they are therefore all included in this workshop version of the paper. 1 Introduction The set of patterns introduced in this paper is aimed at instructors who occasionally want | or have | to teach a class in a foreign language instead of their mother tongue. The patterns are meant to support these instructors in preparing for these classes in such a way that a foreign language will not be a barrier to students' understanding of the course content. This set of patterns is part of a larger project for developing a pattern language for teaching in a foreign language. -

Aurora Tsai's Review of the Diagnosis of Reading in a Second Or Foreign

Reading in a Foreign Language April 2015, Volume 27, No. 1 ISSN 1539-0578 pp. 117–121 Reviewed work: The Diagnosis of Reading in a Second or Foreign Language. (2015). Alderson, C., Haapakangas, E., Huhta, A., Nieminen, L., & Ullakonoja, R. New York and London: Routledge. Pp. 265. ISBN 978-0-415-66290-1 (paperback). $49.95 Reviewed by Aurora Tsai Carnegie Mellon University United States http://www.amazon.com In The Diagnosis of Reading in a Second or Foreign Language, Charles Alderson, Eeva-Leena Haapakangas, Ari Huhta, Lea Nieminen, and Riikka Ullakonoja discuss prominent theories concerning the diagnosis of reading in a second or foreign language (SFL). Until now, the area of diagnosis in SFL reading has received little attention, despite its increasing importance as the number of second language learners continues to grow across the world. As the authors point out, researchers have not yet established a theory of how SFL diagnosis works, which makes it difficult to establish reliable procedures for accurately diagnosing and helping students in need. In this important contribution to reading and diagnostic research, Alderson et al. illustrate the challenges involved in carrying out diagnostic procedures, conceptualize a theory of diagnosis, provide an overview of SFL reading, and highlight important factors to consider in diagnostic assessment. Moreover, they provide detailed examples of tests developed specifically for diagnosis, most of which arise from their most current research projects. Because this book covers a wide variety of SFL reading and diagnostic topics, researchers in applied linguistics, second language acquisition, language assessment, education, and even governmental organizations or military departments would consider it an enormously helpful and enlightening resource on SFL reading. -

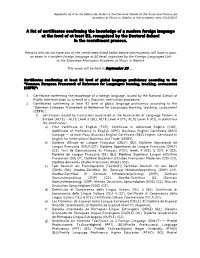

A List of Certificates Confirming the Knowledge of a Modern Foreign Language at the Level of at Least B2, Recognized by the Doctoral School in the Recruitment Process

Appendix no 4 to the Admission Rules to the Doctoral School of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk in the academic year 2020/2021 A list of certificates confirming the knowledge of a modern foreign language at the level of at least B2, recognized by the Doctoral School in the recruitment process. Persons who do not have any of the certificates listed below before matriculation will have to pass an exam in a modern foreign language at B2 level, organized by the Foreign Languages Unit of the Stanisław Moniuszko Academy of Music in Gdańsk. This exam will be held in September 20..... Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1. Certificate confirming the knowledge of a foreign language, issued by the National School of Public Administration as a result of a linguistic verification procedure. 2. Certificates confirming at least B2 level of global language proficiency according to the "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment (CEFR)": 1) certificates issued by institutions associated in the Association of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE) - ALTE Level 3 (B2), ALTE Level 4 (C1), ALTE Level 5 (C2), in particular the certificates: a) First Certificate in English (FCE), Certificate in Advanced English (CAE), Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE), Business English Certificate (BEC) Vantage — at least Pass, Business English Certificate (BEC) -

Language and Linguistics 2009

Visit us at: www.cambridge.org/asia ASIA SALES CONTACTS Cambridge University Press Asia 79 Anson Road #06-04 China – Beijing Office Singapore 079906 Room 1208–09, Tower B, Chengjian Plaza Phone (86) 10 8227 4100 Phone (65) 6323 2701 No. 18, Beitaipingzhuang Road, Haidian District Fax (86) 10 8227 4105 Fax (65) 6323 2370 Beijing 100088, China Email [email protected] Email [email protected] China – Shanghai Office Room N, Floor 19 Phone (86) 21 5301 4700 Zhiyuan Building Fax (86) 21 5301 4710 768, XieTu Road, Shanghai Email [email protected] 200023, China ➤ See page 9 ➤ See page 1 ➤ See page 10 China – Guangzhou Office RM 1501, East Tower, Dong Shan Plaza Phone (86) 20 8732 6913 69 Xian Lie Zhong Lu, Guangzhou 510095 Fax (86) 20 8732 6693 Language and China Email [email protected] China – Hong Kong and other areas Unit 1015–1016, Tower 1 Phone (852) 2997 7500 Millennium City 1, Fax (852) 2997 6230 Linguistics 2009 388 Kwun Tong Road Email [email protected] Kwun Tong, Kowloon Hong Kong, SAR www.cambridge.org/linguistics India Cambridge University Press India Pvt. Ltd. Phone (91) 11 2327 4196 / 2328 8533 Cambridge House, 4381/4, Ansari Road Fax (91) 11 2328 8534 Daryaganj, New Delhi – 110002, India Email [email protected] Japan Sakura Building, 1F, 1-10-1 Kanda Nishiki-cho Phone, ELT (81) 3 3295 5875 ➤ See page 1 ➤ See page 2 ➤ See page 3 Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo – 101-0054 Phone, Academic (81) 3 3291 4068 Japan Email [email protected] Malaysia Suite 9.01, 9th Floor, Amcorp Tower Phone (603) 7954 4043 Amcorp Trade Centre, 18 Persiaran Barat Fax (603) 7954 4127 46050 Petaling Jaya, Malaysia Email [email protected] Philippines 4th Floor, Port Royal Place Phone (632) 8405734/35 118 Rada Street, Legaspi Village Fax (632) 8405734 Makati City, Philippines [email protected] South Korea 2FL, Jeonglim Building Phone (82) 2 2547 2890 254-27, Nonhyun-dong, Gangnam-gu, Fax (82) 2 2547 4411 Seoul 135-010, South Korea Email [email protected] Taiwan 11F-2, No. -

Language Requirements

Language Policy NB: This Language Policy applies to applicants of the 20J and 20D MBA Classes. For all other MBA Classes, please use this document as a reference only and be sure to contact the MBA Admissions Office for confirmation. Last revised in October 2018. Please note that this Language Policy document is subject to change regularly and without prior notice. 1 Contents Page 3 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale Page 4 Summary of INSEAD Language Requirements Page 5 English Proficiency Certification Page 6 Entry Language Requirement Page 7 Exit Language Requirement Page 8 FL&C contact details Page 9 FL&C Language courses available Page 12 FL&C Language tests available Page 13 Language Tuition Prior to starting the MBA Programme Page 15 List of Official Language Tests recognised by INSEAD Page 22 Frequently Asked Questions 2 INSEAD Language Proficiency Measurement Scale INSEAD uses a four-level scale which measures language competency. This is in line with the Common European Framework of Reference for language levels (CEFR). Below is a table which indicates the proficiency needed to fulfil INSEAD language requirement. To be admitted to the MBA Programme, a candidate must be fluent level in English and have at least a practical level of knowledge of a second language. These two languages are referred to as your “Entry languages”. A candidate must also have at least a basic level of understanding of a third language. This will be referred to as “Exit language”. LEVEL DESCRIPTION INSEAD REQUIREMENTS Ability to communicate spontaneously, very fluently and precisely in more complex situations. -

Inventory of Language Certification in Europe a Report to the European

National Foundation for Educational Research Inventory of Language Certification in Europe A Report to the European Commission Directorate General for Education and Culture Jenny Bradshaw Catherine Kirkup March 2006 Acknowledgements We would like to thank the individuals and organisations mentioned below. All the individuals who responded to the online questionnaire, and the organisations which assisted in their distribution. The Eurydice units which provided information on the use of certification in their countries. The Association of Language Testers in Europe The European Association for Language Testing and Assessment We are also very grateful to the following providers, who supplied information on their certificates: Anglia Examinations Syndicate Assessment and Qualifications Alliance Basque Government Cambridge ESOL Centre de Langues Luxembourg Centre for Advanced Language Learning, Hungary Centre for the Greek Language Centre international d'études pédagogiques Centro Linguistico Italiano Dante Alighieri Citogroep CNaVT (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, België/Universiteit van Amsterdam, Nederland) Welsh Joint Education Committee Danish Language Testing Consortium Department of Lithuanian Studies, Vilnius University Escola Oficial de Idiomas (Catalunya) Escuela Oficial de Idiomas (Madrid) European Consortium for the Certificate of Attainment in Modern Languages Finnish National Board of Education Generalitat de Catalunya Goethe-Institut IELTS Consortium Institute of Linguists Educational Trust UK Instituto Cervantes National Examination -

Opções De Vagas

Anexo - Vagas Disponíveis UNIVERSIDADE PAÍS VAGAS IDIOMA 1 PROFICIENCIA IDIOMA 1 OU IDIOMA 2 PROFICIÊNCIA IDIOMA 2 Alemão: Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen Alemanha 5 Alemão OU Inglês mínimo nível B2 proficiência no mínimo nível B2 DSH 2, DSH 3, TestDAF (com 4 ou 5 pontos em todas as áreas, no mínimo 16 pontos) ou equivalente; German Ernst-Abbe-Fachhochschule Jena Alemanha 5 Alemão language proficiency: upper intermediate (e.g. Goethe certificate B2, TestDaF 3-4) Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Hochschule Neu-Ulm Alemanha 3 Alemão Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no mínimo nível B2 OU Inglês proficiência no mínimo nível B2 Alemão: Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Hochschule Ruhr West Alemanha 5 Alemão OU Inglês mínimo nível B1 proficiência no mínimo nível B1 Alemão: Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Hochschule Worms Alemanha 3 Alemão OU Inglês mínimo nível B1 proficiência no mínimo nível B2 DSH 2, DSH 3, TestDaF 4 em todas as habilidades, Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Alemanha 2 Alemão Goethe-Zertifikat C2, UNIcert-certificate III and IV ou OU Inglês Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no mínimo nível B2 proficiência no mínimo nível B2 Alemão: Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de FHWien der WKW Áustria 1 Alemão OU Inglês mínimo B2 proficiência no mínimo nível B2 Francês: Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes Commerciales Bélgica 2 Francês OU Inglês mínimo nível B2 proficiência no mínimo nível B2 Francês: Atestado ou Exame de proficiência no Inglês: Atestado ou Exame de Université Libre de Bruxelles Bélgica 2 Francês OU Inglês mínimo nível B2 proficiência no mínimo nível B2 TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) iBT (internet-based test) score of 80 or PBT (paper-based test) score of 550.