Tanacetum Vulgare L. USDA Plants Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manhattan 41 North Main Gimlet Chocolate Sazerac Smoking Apple Rum Fashion Hop Collins New Pal Highland Park Rosemary Paloma

SPIRITS MANHATTAN 12 RUM FASHION 10 rye whiskey • carpano antica • taylor adgate port wine • white rum • muddled orange & cherry • vanilla syrup • almond syrup cio ciaro amaro • aromatic bitters • brandied cherry HOP COLLINS 10 41 NORTH MAIN 12 gin • fresh lemon juice • IPA • honey CLASSICS vodka • cucumber • basil • simple syrup • fresh lime juice NEW PAL 12 GIMLET 12 SIGNATURES gin • aperol • lillet blanc • grapefruit bitters vodka • elderower liqueur • fresh lime juice HIGHLAND PARK 12 CHOCOLATE SAZERAC 10 rye whiskey • fresh lemon juice • simple syrup • port wine • egg white rye whiskey • crème de cocoa • simple syrup • absinthe rinse SMOKING APPLE 14 ROSEMARY PALOMA 14 mezcal • apple pie moonshine • apple cider • fresh lime juice tequila • fresh grapefruit juice • rosemary simple syrup • rosemary salt rim DRAUGHT BEER PINT or TASTING FLIGHT // 8 LOCAL BEER SELECTIONS your server would be happy to describe our beer on tap this evening. BOTTLED BEER MICHELOB ULTRA 5 SAM ADAMS SEASONAL 6 PERONI 6 COORS LIGHT 5 YUENGLING LAGER 6 STELLA ARTOIS 6 LABATT BLUE 5 HEINEKEN 6 GUINNESS DRAUGHT 6 LABATT BLUE LIGHT 5 BALLAST POINT GRAPEFRUIT SCULPIN 6 BECK’S N/A 5 CORONA 5 WAGNER VALLEY IPA 6 MODELO 6 BLUE MOON 5 1911 CIDER SEASONAL 6 BROOKLYN LAGER 6 WINE SPARKLING DESTELLO • Cava Brut Reserva • Catelonia, Spain G 10 B 32 ZARDETTO • Prosecco NV • Veneto, Italy G 11 B 38 RUFFINO • Moscato D’Asti DOCG • Piedmont, Italy G 10 B 32 BY THE BY GLASS ROSÉ JOLIE FOLLE • Grenache-Syrah • Provence, France G 12 B 46 WHITES HOUSE • Rotating Selection G 9 SAUVION -

Front Door Brochure

012_342020 A 4 4 l b H a n o y l l , a N n Y d A 1 2 v 2 e 2 n 9 u - e 0 0 0 1 For more information about the FRONT DOOR, call your local Front Door contact: Finger Lakes ..............................................855-679-3335 How Can I Western New York ....................................800-487-6310 Southern Tier ..................................607-771-7784, Ext. 0 Get Services? Central New York .....................315-793-9600, Ext. 603 The Front Door North Country .............................................518-536-3480 Capital District ............................................518-388-0398 Rockland County ......................................845-947-6390 Orange County .........................................845-695-7330 Taconic ..........................................................844-880-2151 Westchester County .................................914-332-8960 Brooklyn .......................................................718-642-8576 Bronx .............................................................718-430-0757 Manhattan ..................................................646-766-3220 Queens ..........................................................718-217-6485 Staten Island .................................................718-982-1913 Long Island .................................................631-434-6000 Individuals with hearing impairment: use NY Relay System 711 (866) 946-9733 | NY Relay System 711 www.opwdd.ny.gov Identify s s s s s Contact Information Determine s Assessment Develop Services Support The Front -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Butterflies and Moths of Dorchester County, Maryland, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

2009 Vermilion, Alberta

September 2010 ISSN 0071‐0709 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 57th ANNUAL MEETING OF THE Entomological Society of Alberta November 5‐7, 2009 Vermilion, Alberta Content Entomological Society of Alberta Board of Directors for 2009 .............................................................. 3 Annual Meeting Committees for 2009 ................................................................................................. 3 President’s Address ............................................................................................................................. 4 Program of the 57th Annual Meeting.................................................................................................... 6 Oral Presentation Abstracts ................................................................................................................10 Poster Presentation Abstracts.............................................................................................................21 Index to Authors.................................................................................................................................24 Minutes of the Entomology Society of Alberta Executive/Board of Directors Meeting ........................26 Minutes of the Entomological Society of Alberta 57th Annual General Meeting...................................29 2009 Regional Director to the Entomological Society of Canada Report ..............................................32 2009 Northern Director’s Reports .......................................................................................................33 -

List of Insect Species Which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists

Conservation Biology Research Grants Program Division of Ecological Services © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources List of Insect Species which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists Final Report to the USFWS Cooperating Agencies July 1, 1996 Catherine Reed Entomology Department 219 Hodson Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul MN 55108 phone 612-624-3423 e-mail [email protected] This study was funded in part by a grant from the USFWS and Cooperating Agencies. Table of Contents Summary.................................................................................................. 2 Introduction...............................................................................................2 Methods.....................................................................................................3 Results.....................................................................................................4 Discussion and Evaluation................................................................................................26 Recommendations....................................................................................29 References..............................................................................................33 Summary Approximately 728 insect and allied species and subspecies were considered to be possible prairie specialists based on any of the following criteria: defined as prairie specialists by authorities; required prairie plant species or genera as their adult or larval food; were obligate predators, parasites -

Redalyc.New and Interesting Portuguese Lepidoptera Records from 2007 (Insecta: Lepidoptera)

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Corley, M. F. V.; Marabuto, E.; Maravalhas, E.; Pires, P.; Cardoso, J. P. New and interesting Portuguese Lepidoptera records from 2007 (Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 36, núm. 143, septiembre, 2008, pp. 283-300 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45512164002 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 283-300 New and interesting Po 4/9/08 17:37 Página 283 SHILAP Revta. lepid., 36 (143), septiembre 2008: 283-300 CODEN: SRLPEF ISSN:0300-5267 New and interesting Portuguese Lepidoptera records from 2007 (Insecta: Lepidoptera) M. F. V. Corley, E. Marabuto, E. Maravalhas, P. Pires & J. P. Cardoso Abstract 38 species are added to the Portuguese Lepidoptera fauna and two species deleted, mainly as a result of fieldwork undertaken by the authors in the last year. In addition, second and third records for the country and new food-plant data for a number of species are included. A summary of papers published in 2007 affecting the Portuguese fauna is included. KEY WORDS: Insecta, Lepidoptera, geographical distribution, Portugal. Novos e interessantes registos portugueses de Lepidoptera em 2007 (Insecta: Lepidoptera) Resumo Como resultado do trabalho de campo desenvolvido pelos autores principalmente no ano de 2007, são adicionadas 38 espécies de Lepidoptera para a fauna de Portugal e duas são retiradas. -

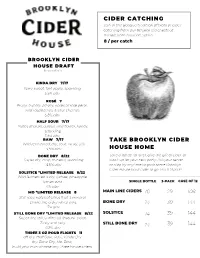

BCH Beverage Menu

CIDER CATCHING Join in the Basque tradition of txotx or cider catching from our 80 year old chestnut barrels from Asturias, Spain. 8 / per catch BROOKLYN CIDER HOUSE DRAFT 8oz pours/bottle KINDA DRY 7/17 Semi-sweet, tart apple, sparkling 5.5% abv ROSÉ 7 Fruity, bubbly, off-dry, notes of rose petal, wild raspberries, & sour cherries 5.8% abv HALF SOUR 7/17 Notes of pickled pear, wild flower, honey, sparkling 5.8% abv RAW 7/17 TAKE BROOKLYN CIDER Wild fermented, dry, sour, funky, still 6.9% abv HOUSE HOME BONE DRY 8/22 Save a bottle for later, give the gift of cider, or Super dry, crisp, mineral, sparkling stock up for your next party. Ask your server 6.9% abv or stop by anytime to grab some Brooklyn Cider House hard cider to go. Mix & Match! SOLSTICE *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 Wild fermented & dry, lychee, pineapple, lemon zest SINGLE BOTTLE 3-PACK CASE OF 12 6% abv MO *LIMITED RELEASE 8 MAIN LINE CIDERS 10 29 108 Still, racy, notes of citrus fruit & mineral. Drinks like a dry white wine BONE DRY 14 39 144 7% abv STILL BONE DRY *LIMITED RELEASE 8/22 SOLSTICE 14 39 144 Super dry, still, unfiltered (natural cider). Zesty and racy. STILL BONE DRY 14 39 144 6.8% abv THREE 3 OZ POUR FLIGHTS 11 off-dry: Half Sour, Rosé, Kinda Dry dry: Bone Dry, Mo, Raw, build your own: choose any three house ciders OTHER CIDER SOUTH HILL "POMM SUR LIE" 8 KITE & STRING - NORTHERN SPY 29 Still, Dry, barrel aged, tannic, acidic, apple skin, roasted nuts Semi-dry. -

Climatological Conditions of Lake-Effect Precipitation Events Associated with the New York State Finger Lakes

1052 JOURNAL OF APPLIED METEOROLOGY AND CLIMATOLOGY VOLUME 49 Climatological Conditions of Lake-Effect Precipitation Events Associated with the New York State Finger Lakes NEIL LAIRD Department of Geoscience, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York RYAN SOBASH School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma NATASHA HODAS Department of Environmental Science, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, New Jersey (Manuscript received 4 June 2009, in final form 11 January 2010) ABSTRACT A climatological analysis was conducted of the environmental and atmospheric conditions that occurred during 125 identified lake-effect (LE) precipitation events in the New York State Finger Lakes region for the 11 winters (October–March) from 1995/96 through 2005/06. The results complement findings from an earlier study reporting on the frequency and temporal characteristics of Finger Lakes LE events that occurred as 1) isolated precipitation bands over and downwind of a lake (NYSFL events), 2) an enhancement of LE precipitation originating from Lake Ontario (LOenh events), 3) an LE precipitation band embedded within widespread synoptic precipitation (SYNOP events), or 4) a transition from one type to another. In com- parison with SYNOP and LOenh events, NYSFL events developed with the 1) coldest temperatures, 2) largest lake–air temperature differences, 3) weakest wind speeds, 4) highest sea level pressure, and 5) lowest height of the stable-layer base. Several significant differences in conditions were found when only one or both of Cayuga and Seneca Lakes, the largest Finger Lakes, had LE precipitation as compared with when the smaller Finger Lakes also produced LE precipitation. -

The Lake Reportersummer 2017 the Lake Reportersummer 2017

THE LAKE REPORTERSUMMER 2017 THE LAKE REPORTERSUMMER 2017 The Annual Meeting is a great place to hear more about current initiatives and watershed topics. 2017 ANNUAL Join us for a business meeting with officer elections, reports from the Chair and Treasurer, and award recognitions. Stay for two great presentations that are sure to MEETING be of interest to all watershed residents. Mission of the Finger Lakes Water Hub Anthony Prestigiacomo, Research Scientist with the Finger Lakes Water Hub, will THURSDAY AUGUST 17 introduce us to the group’s mission of addressing water quality issues across the FLCC STAGE 14 AT 6 PM Finger Lakes region. “State of the Lake” Presentation Kevin Olvany, Watershed Program Manager (Canandaigua Lake Watershed Council) will deliver the evening’s keynote presentation on the current water quality status of Light refreshments will be provided. the Canandaigua Lake watershed. Kevin will share water quality data looking at long A donation of $5 is suggested. RSVP to -term trends from the last 20 years of monitoring, and will identify potential threats [email protected] to the health and overall environment of the lake. Impacts of the area’s recent storm or 394-5030. events will also be discussed. We hope you will join us on August 17th to learn more about what your membership dollars help support. CITIZEN SCIENCE IN ACTION! By Nadia Harvieux, CLWA Community Outreach Committee The Community Outreach Committee has launched three citizen and NYSFOLA science initiatives for the 2017 summer lake sampling season. With will report the the goal of understanding our lake ecosystem better, CLWA is results of the partnering with local, regional and state water quality experts to train sampling in early volunteers in collecting a wide range of data about Canandaigua 2018. -

Section Reports Botany Section 2 Isophrictis Similiella, a Gelechiid Moth, a Florida State Record

DACS-P-00124 Volume 52, Number 5, September - October 2013 DPI’s Bureau of Entomology, Nematology and Plant Pathology (the botany section is included in this bureau) produces TRI- OLOGY six times a year, covering two months of activity in each issue. The report includes detection activities from nursery plant inspections, routine and emergency program surveys, and requests for identification of plants and pests from the public. Samples are also occasionally sent from other states or countries for identification or diagnosis. Highlights Section Reports Botany Section 2 Isophrictis similiella, a gelechiid moth, a Florida State Record. This species is a pest of sunflowers Entomology Section 4 in Midwest and northern United States. It bores into stems and dry seedheads of Asteraceae. Isophrictis similiella (a gelechiid moth) Nematology Section 10 Photograph courtesy of James E. Hayden, DPI Meloidogyne javanica (Treub, 1885) Chitwood, Plant Pathology Section 12 1949, the Javanese root-knot nematode was found infecting the roots of the edible fig, Ficus Our Mission 16 carica. Pseudocercospora abelmoschi and Cercospora malayensis were found on okra (Abelmoschus esculentus), one of the few garden vegetables that thrive in the heat of the Florida summer when Ficus carica roots with galls induced most other vegetables find the relentless hot and by Meloidogyne javanica humid conditions unbearable. Rainfall records Photograph courtesy of Janete A. Brito, DPI were set in the late summer of 2013 over much of North Florida. These weather conditions apparently favored severe okra leaf spot problems, mostly due Pseudocercospora abelmoschi, but also Cercospora malayensis. Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. ex DC. (sissoo tree, Indian rosewood, shisham) was introduced as an ornamental from its native Asia to South Florida by the early 1950s and is now listed by the Florida Abelmoschus esculentus (okra) infected with both Pseudocerco- Exotic Pest Plant Council as a Category II invasive. -

Chrysanthemum Balsamita (L.) Baill.: a Forgotten Medicinal Plant

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Medicine and Biology Vol.15, No 3, 2008, pp. 119 - 124 UC 633.88 CHRYSANTHEMUM BALSAMITA (L.) BAILL.: A FORGOTTEN MEDICINAL PLANT Mohammad-Bagher Hassanpouraghdam1, Seied-Jalal Tabatabaie2, Hossein Nazemiyeh3, Lamia Vojodi4, Mohammad-Ali Aazami1, Atefeh Mohajjel Shoja5 1Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Maragheh, Iran. 2Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Tabriz, Iran. 3Drug Applied Research Center, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran. 4Department of Plant Sciences, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Tabriz, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Summary. Costmary (Chrysanthemum balsamita (L.) Baill. syn. Tanacetum balsamita L.) is one of the most important medicinal and aromatic plants of Azerbaijan provinces in Iran. This plant has been used for more than several centuries as flavor, carminative and cardiotonic in traditional and folk medicine of Iran, and some parts of the world such as the Mediterranean, Balkan and South American countries, but there is scarce information about this plant. In most substances and, for majority of folk and medical applications, costmary is harvested from the natural habitats. This trend i.e. harvests from natural habitats and different ecological conditions lead to the production of different medicinal preparations because of the divergent intrinsic active principle profiles of different plant origins. In addition, harvest from natural habitats can cause deterioration of genetic resources of plant and, the result would be imposing of irreversible destructive effects on the ecological balance of flora and ecosystems. Taking into account the widespread uses of costmary and its preparations in most countries especially in North-West of Iran and Turkey, also because of limited scientific literature for Chrysanthemum balsamita (L.) Baill., this article will survey the literature for different characteristics of costmary and its essential oil for the first time.