Dürer to Goya: Three Centuries of Printmaking from the Needles Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

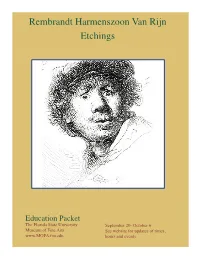

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING in SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00

A Q U A T I N T : P R I N T I N G I N S H A D E S GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY 74 Heath Street Hampstead Village London NW3 1DN AQUATINT: OPENING TIMES: Monday - Friday: 9:30 -18:30 PRINTING IN SHADES Saturday - Sunday: 12:00 - 18:00 GILDENSARTS.COM [email protected] +44 (0)20 7435 3340 G I L D E N ’ S A R T S G A L L E R Y GILDEN’S ARTS GALLERY AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES April – June 2015 Director: Ofer Gildor Text and Concept: Daniela Boi and Veronica Czeisler Gallery Assistant: Costanza Sciascia Design: Steve Hayes AQUATINT: PRINTING IN SHADES In its ongoing goal to research and promote works on paper and the art of printmaking, Gilden’s Arts Gallery is glad to present its new exhibition Aquatint: Printing in Shades. Aquatint was first invented in 1650 by the printmaker Jan van de Velde (1593-1641) in Amsterdam. The technique was soon forgotten until the 18th century, when a French artist, Jean Baptiste Le Prince (1734-1781), rediscovers a way of achieving tone on a copper plate without the hard labour involved in mezzotint. It was however not in France but in England where this technique spread and flourished. Paul Sandby (1731 - 1809) refined the technique and coined the term Aquatint to describe the medium’s capacity to create the effects of ink and colour washes. He and other British artists used Aquatint to capture the pictorial quality and tonal complexities of watercolour and painting. -

The Dialogue of Craft and Architecture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2015 The Dialogue of Craft and Architecture Thomas J. Forker University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Architectural Technology Commons, and the Cultural Resource Management and Policy Analysis Commons Recommended Citation Forker, Thomas J., "The Dialogue of Craft and Architecture" (2015). Masters Theses. 197. https://doi.org/10.7275/7044176 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/197 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIALOGUE OF CRAFT AND ARCHITECTURE A Thesis Presented by THOMAS J. FORKER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE MAY 2015 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE THE DIALOGUE OF CRAFT AND ARCHITECTURE A Thesis Presented by THOMAS J. FORKER Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________ Kathleen Lugosch, Chair ___________________________ Ray Mann, Associate Professor ____________________ Professor Kathleen Lugosch Graduate Program Director Department of Architecture ____________________ Professor Stephen Schreiber Chair Department of Architecture DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents, for their love and support. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors Kathleen Lugosch and Ray Mann. They have been forthright with their knowledge, understanding, and dedicated in their endeavor to work with the students in the department and in the pursuit of a masters of architecture degree with spirit and meaning. -

A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and Brown Ink and Grey Wash, Over an Underdrawing in Black Chalk

Stefano DELLA BELLA (Florence 1610 - Florence 1664) A Saltcellar in the Form of a Mermaid Holding a Shell Pen and brown ink and grey wash, over an underdrawing in black chalk. 179 x 83 mm. (7 x 3 1/4 in.) This charming drawing may be compared stylistically to such ornamental drawings by Stefano della Bella as a design for a garland in the Louvre. Similar drawings for table ornaments by the artist are in the Louvre, the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, the Uffizi and elsewhere. In the conception of this drawing, depicting a mermaid holding a shell above her head, the artist may have recalled Bernini’s Triton fountain in Rome, of which he made a study, now in the Louvre and similar in technique and handling to the present drawing, during his stay in the city in the 1630’s. Artist description: A gifted draughtsman and designer, Stefano della Bella was born into a family of artists. Apprenticed to a goldsmith, he later entered the workshop of the painter Giovanni Battista Vanni, and also received training in etching from Remigio Cantagallina. He came to be particularly influenced by the work of Jacques Callot, although it is unlikely that the two artists ever actually met. Della Bella’s first prints date to around 1627, and he eventually succeeded Callot as Medici court designer and printmaker, his commissions including etchings of public festivals, tournaments and banquets hosted by the Medici in Florence. Under the patronage of the Medici, Della Bella was sent in 1633 to Rome, where he made drawings after antique and Renaissance masters, landscapes and scenes of everyday life. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

Private Collection of Camille Pissarro Works Featured in Swann Galleries’ Old Master-Modern Sale

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Alexandra Nelson October 14, 2016 Communications Director 212-254-4710 ext. 19 [email protected] Private Collection of Camille Pissarro Works Featured in Swann Galleries’ Old Master-Modern Sale New York— On Thursday, November 3, Swann Galleries will hold an auction of Old Master Through Modern Prints, featuring section of the sale devoted to a collection works by Camille Pissarro: Impressionist Icon. The beginning of the auction offers works by renowned Old Masters, with impressive runs by Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt van Rijn. Scarce engravings by Dürer include his 1514 Melencholia I, a well-inked impression estimated at $70,000 to $100,000, and Knight, Death and the Devil, 1513 ($60,000 to $90,000), as well as a very scarce chiaroscuro woodcut of Ulrich Varnbüler, 1522 ($40,000 to $60,000). Rembrandt’s etching, engraving and drypoint Christ before Pilate: Large Plate, 1635-36, is estimated at $60,000 to $90,000, while one of earliest known impressions of Cottages Beside a Canal: A View of Diemen, circa 1645, is expected to sell for $50,000 to $80,000. The highlight of the sale is a private collection of prints and drawings by Impressionist master Camille Pissarro. This standalone catalogue surveys Impressionism’s most prolific printmaker, and comprises 67 lots of prints and drawings, including many lifetime impressions that have rarely been seen at auction. One of these is Femme vidant une brouette, 1880, a scarce etching and drypoint of which fewer than thirty exist. Only three other lifetime impressions have appeared at auction; this one is expected to sell for $30,000 to $50,000. -

Empire of Prints. the Imperial City of Augsburg and the Printed Image In

OPUS Augsburg 2016 Peter Stoll Empire of Prints The Imperial City of Augsburg and the Printed Image in the 17th and 18th Centuries1 Detail from the frontispiece to David Langenmantel’s Historie des Regiments in des Heil. Röm. Reichs Stadt Augspurg (Augsburg 1734); engraving by Jakob Andreas Friedrich: Augsburg city hall; on top of the cartouche the pine cone from the city’s coat of arms; to the right the eagle signifying the Holy Roman Empire. 1 This text, in a Spanish translation, first served as one of the introductory essays in an exhibition catalogue dealing with Augsburg prints as modellos for baroque paintings in Quito, Ecuador (‘El imperio del grabado: La ciudad imperial de Augsburgo y la imagen impresa en los siglos XVII y XVIII’, in: Almerindo E. Ojeda, Alfonso Ortiz Crespo [ed.]: De Augsburgo a Quito: fuentes grabadas del arte jesuita quiteño del siglo XVIII, Quito 2015, pp. 17-66). For the present purpose, all passages of the text which only made sense in the context of the exhibition have been removed. Nonetheless, the 18th century bias of the text as well as the selection of artists which come under closer scrutiny still reflect the origins of the essay. As it was meant to address not only art historians, but also a general interest readership, it contains much basic information about print- making and the cultural history of Augsburg. OPUS Augsburg 2016 / Stoll, Empire of Prints 2 _______________________________________________________________________________________ A very particular type of factory When in 2001 Johan Roger -

Unequal Lovers: a Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design Art, Art History and Design, School of 1978 Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art Alison G. Stewart University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artfacpub Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Stewart, Alison G., "Unequal Lovers: A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art" (1978). Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/artfacpub/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art, Art History and Design, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, School of Art, Art History and Design by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Unequal Lovers Unequal Lovers A Study of Unequal Couples in Northern Art A1ison G. Stewart ABARIS BOOKS- NEW YORK Copyright 1977 by Walter L. Strauss International Standard Book Number 0-913870-44-7 Library of Congress Card Number 77-086221 First published 1978 by Abaris Books, Inc. 24 West 40th Street, New York, New York 10018 Printed in the United States of America This book is sold subject to the condition that no portion shall be reproduced in any form or by any means, and that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. -

Printmaking Through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012

Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Table of Contents Page Contents 2 Image List 3 Printmaking as Art 6 Glossary of Printing Terms 7 A Brief History of Printmaking Written by Jennifer Jensen 10 Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap , Rembrandt Written by Hailey Leek 11 Lesson Plan for Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap Written by Virginia Catherall 14 Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo, Hokusai Written by Jennifer Jensen 16 Lesson Plan for Kintai Bridge, Province of Suwo Written by Jennifer Jensen 20 Lambing , Leighton Written by Kathryn Dennett 21 Lesson Plan for Lambing Written by Kathryn Dennett 32 Madame Louison, Rouault Written by Tiya Karaus 35 Lesson Plan for Madame Louison Written by Tiya Karaus 41 Prodigal Son , Benton Written by Joanna Walden 42 Lesson Plan for Prodigal Son Written by Joanna Walden 47 Flotsam, Gottlieb Written by Joanna Walden 48 Lesson Plan for Flotsam Written by Joanna Walden 55 Fourth of July Still Life, Flack Written by Susan Price 57 Lesson Plan for Fourth of July Still Life Written by Susan Price 59 Reverberations, Katz Written by Jennie LaFortune 60 Lesson Plan for Reverberations Written by Jennie LaFortune Evening for Educators is funded in part by the StateWide Art Partnership and the Professional Outreach Programs in the Schools (POPS) through the Utah State Office of Education 1 Printmaking through the Ages Utah Museum of Fine Arts • www.umfa.utah.edu Lesson Plans for Educators • March 7, 2012 Image List 1. Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn (1606-1669), Dutch Self Portrait in a Velvet Cap with Plume , 1638 Etching Gift of Merrilee and Howard Douglas Clark 1996.47.1 2. -

AEAH 4840 TOPICS, CRAFT 4840. Topics in the History of Crafts. 3

Instructor: Professor Way Term: Spring 2017 Office: Art Building 212 Class time: Monday 5:00-7:50pm Office Hours: please schedule in advance through email Meeting Place: Art 226 Monday, 4:00-5:00, Tuesday 4:00-5:00, Thursday 4:00-5:00 Email: [email protected] – best way to reach me AEAH 4840 TOPICS, CRAFT 4840. Topics in the History of Crafts. 3 hours. Selected topics in the history of crafts. Prerequisite(s): ART 1200 or 1301, 2350 and 2360, or consent of instructor. TOPIC – CRITICAL HISTORIES OF CRAFT AND ART HISTORY This course explores how history of art survey texts represent and tell us about craft—what do they have to say about craft, and how do they say it? We are equally interested in where and how these art history survey texts neglect craft. What is missing when histories of art do not include craft? Additionally, we want to think about history of craft texts. Should they include the same agents and situations we find in histories of art, such as famous makers and collectors, the rich and the royal, politics at the highest level, and economics, power, and desire? Also, is it possible to trace influence in craft as we expect to find it discussed in histories of art? What would influence explain about craft? Should a history of craft include features we don’t expect to find in histories of art? Overall, what scholarship and methods make a history of craft? These types of questions ask us to notice standards and expectations shaping knowledge in academic fields, such as art history and the history of craft. -

DRYPOINT-WOODCUT Always Loved Those Images, and I Wanted to a Certain Amount of Unpredictability Learn from Cassatt’S Process,” Heck Says

that use the symbol of the heart to explore ideas of love and emotion. A somewhat similar approach is taken in the recent Printmaking series “Fascinators,” in which Heck adorns A passion for printmaking unites these four accomplished artists, who her young subjects with headpieces shaped like Möbius strips. each work with a different process. Heck’s work combines two traditional printmaking processes: drypoint, an intaglio process, and woodcut, a relief process. In BY AUSTIN R. WILLIAMS intaglio processes—such as engraving, etch- ing and drypoint—marks are carved into a Printmaking is drawing’s first cousin. In both metal plate using one of several methods. disciplines artists work directly with their hands Those indentations are filled with ink, and to create lines and tones, ultimately resulting in a when the plate is pressed to paper, the ink is finished work on paper. But printmaking involves transferred to the paper. In relief processes, an additional array of tools and techniques that have such as woodcut and linocut, the opposite occurs. In these methods the artist carves fascinated artists for centuries. Every printmaking process offers its own sort of beauty while also away the negative parts of the image and ink imposing certain constraints on the artist. Here we TODAY is applied to the remaining, raised portions explore the work of four printmakers, who share their of the plate, which is then pressed to paper. thoughts on their chosen printmaking processes. Heck was inspired to combine intaglio and relief processes by Mary Cassatt (1844– 1926), who in the late 1800s produced color ELLEN HECK: etchings inspired by Japanese woodcuts that had recently been exhibited in Paris.