Experimental SEFDM Pipelined Iterative Detection Architecture with Improved Throughput

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Experiment-8

Chapter 1 Experiment-8 1.1 Single Sideband Suppressed Carrier Mod- ulation 1.1.1 Objective This experiment deals with the basic of Single Side Band Suppressed Carrier (SSB SC) modulation, and demodulation techniques for analog commu- nication.− The student will learn the basic concepts of SSB modulation and using the theoretical knowledge of courses. Upon completion of the experi- ment, the student will: *UnderstandSSB modulation and the difference between SSB and DSB modulation * Learn how to construct SSB modulators * Learn how to construct SSB demodulators * Examine the I Q modulator as SSB modulator. * Possess the necessary tools to evaluate and compare the SSB SC modulation to DSB SC and DSB_TC performance of systems. − − 1.1.2 Prelab Exercise 1.Using Matlab or equivalent mathematics software, show graphically the frequency domain of SSB SC modulated signal (see equation-2) . Which of the sign is given for USB− and which for LSB. 1 2 CHAPTER 1. EXPERIMENT-8 2. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to generate SSB SC signal. − 3. Draw a block diagram and explain two method to demodulate SSB SC signal. − 4. According to the shape of the low pass filter (see appendix-1), choose a carrier frequency and modulation frequency in order to implement LSB SSB modulator, with minimun of 30 dB attenuation of the USB component. 1.1.3 Background Theory SSB Modulation DEFINITION: An upper single sideband (USSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f <fcwhere fc, is the carrier frequency. A lower single| | sideband (LSSB) signal has a zero-valued spectrum for f >fc where fc, is the carrier frequency. -

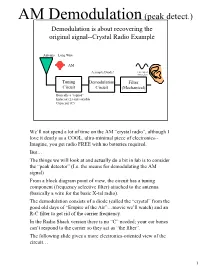

AM Demodulation(Peak Detect.)

AM Demodulation (peak detect.) Demodulation is about recovering the original signal--Crystal Radio Example Antenna = Long WireFM AM A simple Diode! (envelop of AM Signal) Tuning Demodulation Filter Circuit Circuit (Mechanical) Basically a “tapped” Inductor (L) and variable Capacitor (C) We’ll not spend a lot of time on the AM “crystal radio”, although I love it dearly as a COOL, ultra-minimal piece of electronics-- Imagine, you get radio FREE with no batteries required. But… The things we will look at and actually do a bit in lab is to consider the “peak detector” (I.e. the means for demodulating the AM signal) From a block diagram point of view, the circuit has a tuning component (frequency selective filter) attached to the antenna (basically a wire for the basic X-tal radio). The demodulation consists of a diode (called the “crystal” from the good old days of “Empire of the Air”…movie we’ll watch) and an R-C filter to get rid of the carrier frequency. In the Radio Shack version there is no “C” needed; your ear bones can’t respond to the carrier so they act as “the filter”. The following slide gives a more electronics-oriented view of the circuit… 1 Signal Flow in Crystal Radio-- +V Circuit Level Issues Wire=Antenna -V time Filter: BW •fo set by LC •BW set by RLC fo music “tuning” ground=0V time “KX” “KY” “KZ” frequency +V (only) So, here’s the incoming (modulated) signal and the parallel L-C (so-called “tank” circuit) that is hopefully selective enough (having a high enough “Q”--a term that you’ll soon come to know and love) that “tunes” the radio to the desired frequency. -

Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications

Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications Vivek Mangal Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2019 Vivek Mangal All Rights Reserved Abstract Energy-Detecting Receivers for Wake-Up Radio Applications Vivek Mangal In an energy-limited wireless sensor node application, the main transceiver for communication has to operate in deep sleep mode when inactive to prolong the node battery lifetime. Wake-up is among the most efficient scheme which uses an always ON low-power receiver called the wake-up receiver to turn ON the main receiver when required. Energy-detecting receivers are the best fit for such low power operations. This thesis discusses the energy-detecting receiver design; challenges; techniques to enhance sensitivity, selectivity; and multi-access operation. Self-mixers instead of the conventional envelope detectors are proposed and proved to be op- timal for signal detection in these energy-detection receivers. A fully integrated wake-up receiver using the self-mixer in 65 nm LP CMOS technology has a sensitivity of −79.1 dBm at 434 MHz. With scaling, time-encoded signal processing leveraging switching speeds have become attractive. Baseband circuits employing time-encoded matched filter and comparator with DC offset compen- sation loop are used to operate the receiver at 420 pW power. Another prototype at 1.016 GHz is sensitive to −74 dBm signal while consuming 470 pW. The proposed architecture has 8 dB better sensitivity at 10 dB lower power consumption across receiver prototypes. -

ES442 Lab 6 Frequency Modulation and Demodulation

ES442 Lab#6 ES442 Lab 6 Frequency Modulation and Demodulation Objective 1. Build simple FM demodulator by using frequency discriminator 2. Build simple envelope detector for FM demodulation. 3. Using MATLAB m-file and simulink to implement FM modulation and demodulation. Part List 1uF capacitor (2); 10.0Kohm resistor, 1.0Kohm resistor, Power supply with +/-5V, Scope and frequency analyzer, FM signal Generator. Estimated Time About 90 minutes. Introduction Frequency modulation is a form of modulation, which represents information as variations in the instantaneous frequency of a carrier wave. In analog applications, the carrier frequency is varied in direct proportion to changes in the amplitude of an input signal. This is shown in Fig. 1. Figure 1, Frequency modulation. The FM-modulated signal has its instantaneous frequency that varies linearly with the amplitude of the message signal. Now we can get the FM-modulation by the following: where Kƒ is the sensitivity factor, and represents the frequency deviation rate as a result of message amplitude change. The instantaneous frequency is: Ver 2. 1 ES442 Lab#6 The maximum deviation of Fc (which represents the max. shift away from Fc in one direction) is: Note that The FM-modulation is implemented by controlling the instantaneous frequency of a voltage-controlled oscillator(VCO). The amplitude of the input signal controls the oscillation frequency of the VCO output signal. In the FM demodulation what we need to recover is the variation of the instantaneous frequency of the carrier, either above or below the center frequency. The detecting device must be constructed so that its output amplitude will vary linearly according to the instantaneous freq. -

Easy Fourier Analysis

Easy Fourier Analysis http://www.complextoreal.com/base.htm SpectrumDCInformationSignal term at 2w on csignal the positivenegative x-axis Half is up This half is shifted. down shifted. Charan Langton, The Carrier Editor fm = -1 fm = -9, fc-9,-9 -8, = -8, -8-7 -7 -9, -8, -7 SIGNAL PROCESSING & SIMULATION NEWSLETTER Baseband, Passband Signals and Amplitude Modulation The most salient feature of information signals is that they are generally low frequency. Sometimes this is due to the nature of data itself such as human voice which has frequency components from 300 Hz to app. 20 KHz. Other times, such as data from a digital circuit inside a computer, the low rates are due to hardware limitations. Due to their low frequency content, the information signals have a spectrum such as that in the figure below. There are a lot of low frequency components and the one-sided spectrum is located near the zero frequency. Figure 1 - The spectrum of an information signal is usually limited to low frequencies The hypothetical signal above has four sinusoids, all of which are fairly close to zero. The frequency range of this signal extends from zero to a maximum frequency of fm. We say that this signal has a bandwidth of fm. In the time domain this 4 component signal may looks as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2 - Time domain low frequency information signal 1 of 18 1/25/2008 3:42 AM Easy Fourier Analysis http://www.complextoreal.com/base.htm Now let’s modulate this signal, which means we are going to transfer it to a higher (usually much higher) frequency. -

EE133 Winter 2004 1

Prelab 1 - AM Modulation - Prof. Dutton - EE133 Winter 2004 1 EE133 - Prelab 1 Amplitude Modulation and Demodulation 1 Introduction This week we will be taking a look at the amplitude modulation (AM) scheme. In this process, the amplitude of the carrier signal is varied so that it is proportional to the instantaneous amplitude of the modulating signal. With the invention of oscillators, this scheme quickly supplanted the first spark-gap transmitters. They did so because AM supported the easy transmission of voice while allowing more people to transmit without interfering with each other. For an oscillating electrical signal to be transmitted through the air, it must first be converted into elec- tromagnetic radiation. To maximize efficiency of transmission, the physical dimensions of the transmitting and receiving antennas must be on the same order of magnitude as the wavelength of the transmitted signal (often a quarter wavelength). For audio signals, whose frequencies range from 20 Hz to 20 kHz, this corre- sponds to wavelengths from 15 to 15000 km. As you can probably guess, an antenna of this length would be absurd for general applications. AM solves this problem by using a ’slow’ moving audio signal to modulate a fast moving, radio signal. The fast signal is called the carrier signal, and the audio frequency signal is typically called the modulating signal. Typical carrier frequencies range from 30 kHz to upwards of 30 GHz. By using a carrier frequency, users can ’tune’ into a particular transmitter. With the old spark-gap transmit- ters, every user heard all transmitters that were within range. -

Detection and Classification of Frequency-Hopped Spread Spectrum Signals James Eric Dunn Iowa State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Repository @ Iowa State University Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 Detection and classification of frequency-hopped spread spectrum signals James Eric Dunn Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Electrical and Electronics Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, James Eric, "Detection and classification of frequency-hopped spread spectrum signals " (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10027. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10027 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Product Demodulation - Synchronous & Asynchronous

PRODUCT DEMODULATION - SYNCHRONOUS & ASYNCHRONOUS INTRODUCTION...............................................................................98 frequency translation..................................................................98 the process................................................................................................98 interpretation ............................................................................................99 the demodulator .......................................................................100 ω ω synchronous operation: 0 = 1 ...........................................................100 carrier acquisition...................................................................................101 ω ω asynchronous operation: 0 =/= 1 .....................................................101 signal identification .................................................................101 demodulation of DSBSC........................................................................102 demodulation of SSB .............................................................................102 demodulation of ISB ..............................................................................103 EXPERIMENT .................................................................................103 synchronous demodulation ......................................................103 asynchronous demodulation ....................................................104 SSB reception.........................................................................................105 -

Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing with Index-Modulated Non-Orthogonal Subcarriers

POSTPRINT (ACCEPTED VERSION), DOI: 10.1109/LWC.2018.2867869 1 Spectrally Efficient Frequency Division Multiplexing With Index-Modulated Non-Orthogonal Subcarriers Miyu Nakao, Student Member, IEEE, and Shinya Sugiura, Senior Member, IEEE Abstract—In this letter, we propose a novel index-modulated typically limited to as few as tens of non-orthogonal subcar- non-orthogonal spectrally efficient frequency-division multiplex- riers. ing (SEFDM) scheme, in order to attain a higher bandwidth Index modulation (IM) [10] is a recent promising technique efficiency than the conventional orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (OFDM) and SEFDM counterparts. More specifi- that is capable of achieving specific merits over multiplexing. cally, the recent index modulation concept is amalgamated with The IM principle is based on the activation of a subset of SEFDM, for the sake of reducing the effects of intercarrier multiple communication resources in the space, time, and interference while benefiting from SEFDM’s increased spectral frequency domains, where the combination of activated in- efficiency. We also formulate a low-complexity log-likelihood ratio dices is used for conveying information bits, in addition to (LLR)-based detection algorithm, which allows the proposed SEFDM to operate in the configuration of an arbitrarily high conventional modulated symbols. Most recently, in [11], time- number of subcarriers. Our simulation results demonstrate that domain IM is combined with FTN signaling, where a high the proposed SEFDM scheme outperforms the conventional sparsity of IM symbols allows us to reduce the effects of FTN- SEFDM and OFDM, especially in a low-rate scenario. specific ISI while benefiting from the FTN-specific increased Index Terms—Faster-than-Nyquist, index modulation, interfer- bandwidth efficiency. -

Metal Detector Kit

METAL DETECTOR KIT MODEL K-26 Assembly and Instruction Manual ELENCO® Copyright © 2012, 1989 by Elenco® Electronics, Inc. All rights reserved. Revised 2012 REV-F 753226 No part of this book shall be reproduced by any means; electronic, photocopying, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. PARTS LIST If you are a student, and any parts are missing or damaged, please see instructor or bookstore. If you purchased this metal detector kit from a distributor, catalog, etc., please contact ELENCOTM (address/phone/e-mail is at the back of this manual) for additional assistance, if needed. RESISTORS Qty. Symbol Description Color Code Part # r 1R2 4.7kΩ 1/4W 5% yellow-violet-red-gold 144700 r 1 R1 15kΩ 1/4W 5% brown-blue-orange-gold 151500 r 1 P1 Trim Pot 50kΩ 191552 CAPACITORS Qty. Symbol Description Part # r 1 C1 680pF Discap (681) 226880 r 1 C2 0.0015μF Discap (152) 231517 SEMICONDUCTORS Qty. Symbol Description Part # r 1 Q1 Transistor MPS5172 325172 MISCELLANEOUS Qty. Symbol Description Part # r 1 PC Board 518026 r 1 S1 Switch 541102 r 1 B1 Battery Snap 9V 590098 r 1 Wire #26 Enamel 45’ 846000 PARTS IDENTIFICATION Resistor Transistor Capacitor Switch Trim Pot Battery Snap Discap IDENTIFYING RESISTOR VALUES IDENTIFYING CAPACITOR VALUES Use the following information as a guide in properly Capacitors will be identified by their capacitance value in identifying the value of resistors. pF (picofarads), nF (nanofarads), or μF (microfarads). Most capacitors will have their actual value printed on them. Some capacitors may have their value printed in the following manner. -

Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing for Wireless Communications Hua Zhang

Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing for Wireless Communications A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty by Hua Zhang In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical and Computer Engineering School of Electrical and Computer Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology November 11, 2004 Copyright c 2004 by Hua Zhang Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing for Wireless Communications Approved by: Professor Gordon L. St¨uber, Professor Gregory D. Durgin, Committee Chair, Electrical and Com- Electrical and Computer Engineering puter Engineering Professor Ye (Geoffrey) Li, Advisor Professor Xinxin Yu, Electrical and Computer Engineering School of Mathematics Professor Guotong Zhou, Electrical and Computer Engineering Date Approved: November 16, 2004 To my parents, Zhang Zhongkang and Gong Huiju ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to express my sincere thanks to my advisor, Dr. Geoffrey (Ye) Li, for his support, encouragement, guidance, and trust throughout my Ph.D study. He teaches me not only the way to do research but the wisdom of living. He is always available to give me timely and indispensable advice. I can never forget the days and nights he spent on my papers. Three years is short compared with one’s life, but it is enough to change one’s whole life. What I learned within the three years working with Dr. Li established a basis that could lead me to the future success. All I could say is that I can never ask for any more from my advisor. Next, I would like to thank Dr. Gordon L. St¨uber, Dr. Guotong Zhou, and Dr. -

Radio Frequency Signal Detection by Ballistic Transport in Yshaped

Radio frequency signal detection by ballistic transport in Y-shaped graphene nanoribbons G.Deligeorgis 1,2 *, F.Coccetti 1,2, G. Konstantinidis 3 and R.Plana 1,2 1CNRS, LAAS, 7 avenue du colonel Roche, F-31400 Toulouse, France 2Univ de Toulouse, LAAS, F-31400 Toulouse, France. 3Foundation for Research & Technology Hellas (FORTH) P.O. BOX 1527, Vassilika Vouton, Heraklion 711 10, Crete, Greece We report on the fabrication and room temperature measurements of a high frequency electrical signal detector. The device is based on the ballistic transport in graphene to detect a high frequency signal. The observed response is linear in the considered power range (-40dBm – 0dBm) and exhibits a sensitivity as high as 10 Volts/Watt. Finally the device detected signals up to 50GHz with a maximum response at 10GHz. This device outperforms any previously reported carbon based detectors in frequency response and compares to current state of the art Schottky based detectors in dynamic range. Graphene is attracting considerable attention in the past ten years, since its isolation by A. Geim and K. Novoselov [1]. The rates at which achievements are made public is astonishing. Although in electronics the main focus was towards transistors [2–4] where ultra fast operating speeds were promised, graphene has also surfaced at the epi-center of recent advances in sensing. Specifically chemical sensing [5], DNA sequencing [6], [7] and light detectors [8] operating in the GHz range have been demonstrated by exploiting the unique properties of the material. Graphenes' ability to transfer carriers with little or no scattering over a large distance [9], [10], has been proposed as a major feature for spintronics [11], [12] as well as for even more exotic effects such as the “Veselago” lensing effect [13].