Rumor and the Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2010 Julia Silvia Feldhaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2010 Julia Silvia Feldhaus ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Between Commodification and Emancipation: Image Formation of the New Woman through the Illustrated Magazine of the Weimar Republic By Julia Silvia Feldhaus A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in German Written under the direction of Martha B. Helfer And Michael G. Levine And approved by ____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ _____________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2010 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Between Commodification and Emancipation: Image Formation of the New Woman through the Illustrated Magazine of the Weimar Republic By JULIA SILVIA FELDHAUS Dissertation Directors: Martha B. Helfer Michael G. Levine This dissertation investigates the conflict between the powerful emancipatory image of the New Woman as represented in the illustrated magazines of the Weimar Republic and the translation of this image into a lifestyle acted out by women during this era. I argue that while female journalists promote the image of the New Woman in illustrated magazines as a liberating opening onto self-determination and self- management, this very image is simultaneously and paradoxically oppressive. For women to shake off the inheritance of a patriarchal past, they must learn to adjust to a new identity, one that is still to a large extent influenced by and in the service of men. The ideal beauty image designed by female journalists as a framework for emancipation in actuality turned into an oppressive normalization in professional and social markets in which traditional rules no longer obtained. -

To Children I Give My Heart Vasily

TO CHILDREN I GIVE MY HEART VASILY SUKHOMLINSKY (Translated from the Russian by Holly Smith) From the Publishers Vasily Alexandrovich Sukhomlinsky (1918-1970) devoted thirty-five years of his short life to the upbringing and instruction of children. For twenty-nine years he was director of a school in the Ukrainian village of Pavlysh, far away from the big cities. For his work in education, he was awarded the titles of Hero of Socialist Labour and Merited Teacher of the Ukrainian SSR; and elected Corresponding Member of the Academy of Pedagogical Science of the USSR. What is the essence of Vasily Sukhomlinsky's work as an educator? Progressive educators have long tried to merge upbringing and instruction into one educational process. This dream was realized in the educational work of Sukhomlinsky. To see an individual in every school child - this was the essence of his educational method and a necessary requirement for anyone who hopes to raise and teach children. Vasily Sukhomlinsky showed in theory and practice that any healthy child can get a modern secondary education in an ordinary public school without any separation of children into group of bright and less bright. This was no new discovery. But he found the sensible mean that enable, the teacher to lead the child to knowledge in keeping with the national educational programme. The main thing for Sukhomlinsky was to awaken the child's desire to learn, to develop a taste for self-education and self-discipline. Sukhomlinsky studied each of his pupils, consulting with the other teachers and with the parents, comparing his own thoughts with the views of the great educators of the past and with folk wisdom. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

House Cocktails Rose and Sparkling White Wines Red Wines

house cocktails rose and sparkling SEGURA VIUDAS Cava Brut, Torrelavit, Spain 8/31 BANKHEAD 12 Hendrick’s, St. Germain, lime, cucumber BROADBENT Vihno Verde, Portugal 8/31 SEDOSA Rosé, Spain 9/35 PROSÉ 10 CREMANT DE BOURGOGNE Sparkling Rosé, France 15/59 rosé, peach schnapps cranberry, champagne OSTRO Prosecco, Prata di Pordennone, Italy 10/39 POL ROGERS Brut Extra Cuvée Réserve, Champagne, France 110 HEMINGWAY 10 Bacardi, St. Germain grapefruit juice, lime twist white wines WINTER MULE 10 FOLONARI DELLE VENEZIE Pinot Grigio, Italy 8/31 Tito’s, white cranberry, lemon, ginger beer LEITZ Riesling, Rheingau, Germany 8/31 WHITE‘S BAY Sauv. Blanc, Marlborough, N. Zealand 9/35 FRENCH 75 10 Bombay Sapphire, champagne, lemon BIG FIRE Pinot Gris, Willamette Valley, OR 12/47 LINCOURT ‘STEEL’ Chardonnay, Santa Barbara, CA 10/39 OLD FASHIONED 11 ROTH ESTATE Chardonnay, Sonoma Coast, CA 12/47 Bulleit bourbon, orange bitters orange peel, bordeaux cherry SONOMA CUTRER Chardonnay, Sonoma, CA 16/65 PIMM’S CUP 9 Pimm’s No. 1, lime, lemon, ginger beer red wines ESPRESSO MARTINI 12 UNDERWOOD Pinot Noir, Oregon 9/35 Pinnacle Whipped, Kahlua, cold brew VOTRE SANTÉ Pinot Noir, Monterey, CA 10/39 DIORA LA PETITE GRACE Pinot Noir, Monterey, CA 14/55 WATERBROOK RESERVE Merlot, Columbia Valley, WA 65 SEPTIMA Malbec, Mendoza, Argentina 8/31 CHUCK’S 20 OZ. HOUSE PUNCH: FARMHOUSE Red Blend, Sonoma County, CA 8/31 MOUNT PEAK RATTLESNAKE Zinfandel, Sonoma, CA 90 FOXGLOVE Cabernet, Paso Robles, CA 11/43 W/ SOUVENIR CUP GOLDSCHMIDT Cabernet, Alexander Valley, CA 14/55 -

Hermann Hesse

HERMANN H E SSE: THE ROLE OF DEATH IN HIS DEVELOPING CONCEPT OF THE SELF HERMANN HESSE THE ROLE OF DEATH IN HIS DEVELOPING CONCEPT OF THE SELF By June Caroline Schmid, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts McMaster University May 1969 MASTER OF ARTS McMaster University (GERMAN) Hamilton, Ontario Title: Hermann Hesse: The Role of Death in his Developing Concept of the Self. Author: June Caroline Schmid, B.A. Supervisor: Mr. J. Lawson Number of Pages: iv, 120 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. David Stewart for the initial inspiration of this thesis, but I am particularly indebted to Mr. James Lawson for his encouragement and for the effort he made with his painstaking advice to see this work through to its completion. My thanks are due also to the readers, Dr. Karl Denner, and Dr. Robert Van Dusen for their time and support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I Demian: "The Bird Fights its Way 12 out of the Egg" Chapter II Klein, Klingsor: The Problems of 32 Flight Chapter III Siddhartha: Stages of Flight 48 Chapter IV steppenwolf: Another Bird, Another 68 Egg Conclusion 89 Footnotes 98 Bibliography 119 iv Introduction Hermann Hesse was born in Calw in 1877, into a family of devout Christian missionaries whose work in China and India combined an international breadth of spirit with the narrow protestant piety of the small country town. 1 His family's bonds with the Orient influenced Hesse as strongly as did its fervent Christian faith. -

Forecast 1954

. UTRIGGER CAN0E CLUB JUNE FORECAST 1954 ‘'It’s Kamehameha Day—Come Buy a Lei" (This is a scene we hope will never disappear in Hawaii.) flairaii Visitors Bureau Pic SEE PAGE 5 — ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR Fora longer smoother ride... Enjoy summer’s coolest drink. G I V I AND Quinac The quickest way to cool contentment in a glass . Gin-and-Quinac. Just put IV2 ounces of gin in a tall glass. Plenty of ice. Thin slice of P. S. Hnjoy Q u in a c as a delicious beverage. Serve lemon or lime. Fill with it by itself in a glass with Quinac . and you have an lots of ice and a slice of easy to take, deliciously dry, lemon or lime. delightfully different drink. CANADA DRY BOTTLING CO. (HAWAII) LTD. [2] OUTRIGGER CANOE CLUB V o l. 13 N o. « Founded 190S WAIKIKI BEACH HONOLULU, HAWAII OFFICERS SAMUEL M. FULLER...............................................President H. VINCENT DANFORD............................ Vice-President MARTIN ANDERSON............................................Secretary H. BRYAN RENWICK..........................................Treasurer OIECASI DIRECTORS Issued by the Martin Andersen Leslie A. Hicks LeRoy C. Bush Henry P. Judd BOARD OF DIRECTORS H. Vincent Danford Duke P. Kahanamoku William Ewing H. Bryan Renwlck E. W. STENBERG.....................Editor Samuel M. Fuller Fred Steere Bus. Phone S-7911 Res. Phone 99-7664 W illard D. Godbold Herbert M. Taylor W. FRED KANE, Advertising.............Phone 9*4806 W. FREDERICK KANE.......................... General Manager CHARLES HEEf Adm in. Ass't COMMITTEES FINANCE—Samuel Fuller, Chairman. Members: Les CASTLE SW IM -A. E. Minvlelle, Jr., Chairman. lie Hicks, Wilford Godbold, H. V. Danford, Her bert M. -

It's PORCH Season

HOME OUTDOOR LIVING it’s PORCH season The time for winter hibernating has passed. Turn your porch into a space that will tempt you to stay outdoors until the first snowflakes start falling again. chic & TRADITIONAL 1 Do you dream of shingle-clad MAJOR PIECES bungalows and garden Approach the parties? Try on a new-traditional layout as you would look. Start with wicker or an indoor living room rattan furniture and bold prints. with comfortable seating in traditional shapes. Try a wicker settee that mimics the silhouette of a scroll-arm sofa, left, and deep armchairs. 2 HIGH DEFINITION Anchor the seating arrangement with an outdoor rug. Black-and-white is a perennially sophisticated choice, and a graphic print helps camouflage dirt. Choose the pattern to kick the formality up (geometric fretwork) or down (thick stripes). 3 PUNCHY COLOR Accessories in saturated oranges and hot pinks energize the neutral backdrop. Contrast geometrics with at least one botanical or abstract print for personality. 4 SLEEK FINISH A hint of glamour keeps a traditional scheme from looking staid. Try a high-gloss accent like a glazed ceramic garden stool. PHOTO: TRIA GIOVAN 38 | April 2018 BY MALLORY ABREU HOME OUTDOOR LIVING easy & BEACHY No matter how far you are from the coast, this casual style says relaxation. Woven textures and sunny colors are at its core. 1 AIRY FURNITURE Look for pieces with open frames and lighter lines—something the ocean breeze could pass through. Pale rattan and driftwood-like finishes feel right here. 2 ORGANIC TEXTURE Beachy style relies on lots of natural texture. -

The Death of Christian Culture

Memoriœ piœ patris carrissimi quoque et matris dulcissimœ hunc libellum filius indignus dedicat in cordibus Jesu et Mariœ. The Death of Christian Culture. Copyright © 2008 IHS Press. First published in 1978 by Arlington House in New Rochelle, New York. Preface, footnotes, typesetting, layout, and cover design copyright 2008 IHS Press. Content of the work is copyright Senior Family Ink. All rights reserved. Portions of chapter 2 originally appeared in University of Wyoming Publications 25(3), 1961; chapter 6 in Gary Tate, ed., Reflections on High School English (Tulsa, Okla.: University of Tulsa Press, 1966); and chapter 7 in the Journal of the Kansas Bar Association 39, Winter 1970. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or except in cases where rights to content reproduced herein is retained by its original author or other rights holder, and further reproduction is subject to permission otherwise granted thereby according to applicable agreements and laws. ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-1-932528-51-0 ISBN-10 (eBook): 1-932528-51-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senior, John, 1923– The death of Christian culture / John Senior; foreword by Andrew Senior; introduction by David Allen White. p. cm. Originally published: New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington House, c1978. ISBN-13: 978-1-932528-51-0 1. Civilization, Christian. 2. Christianity–20th century. I. Title. BR115.C5S46 2008 261.5–dc22 2007039625 IHS Press is the only publisher dedicated exclusively to the social teachings of the Catholic Church. -

Debut of the Andrea Doria

9ieLOOKOUT HERE IS A VERY PLEASANT WAY to make a contribution to our funds while actually spending money for your own needs. The Institute has been invited The Lookout to share in the proceeds of Lewis & Conger's annual " Name-Your-Own-Charity VOL. XLIV February, 1953 NO. 2 Sale, " which lasts throughout the month of March. When you make purchases at their store, located at Sixth Avenue and 45th Street, please mention the Seamen's Church Institute of New York and we will receive from the store / ' 1 0"10 of the total amount you spent for your own needs. Please tell your .",; t,;. friends about it. ," -d 'O r --- !l-~ - <I " ,. / '" .. .. ;/1 )j # .. .fr ' ~ .- " 'i~ t~ ':", ...... - At ~ '-.. 1llllim! !. int' Ph M(} VOl. XLIV FEBRUARY. 1953 Th e Andrea Dorio decked out for her debut, Copyright 1953 by the Seamen's Church Instit.ute of /\' ew rork Debut of the Andrea Doria $ 1.00 per year Wc per copy Published Monthly Gifts of $5.00 per year and over include a year's subscription ROrDLY bearing the distinction of automatic depth ounding meler and an a transatl antic first: an "emerald electronic eye \ hich gives her a \' i!'i ibilily CLARENCE G. MlCHALlS THOMAS ROBERTS P President Secretary and Treasurer liled sw imming pool" for each passenge r of 40 miles under any co ndilions. Her REV. RAYMOND S. HALL, D.O. TOM BAAB cia s- a splendid blow Ior democracy two groups of turbi nes and twi n 18-lon Director Editor the S .5. Andrea Doria of the Ita li an Li ne propell ers cul a 50,000 h.p. -

New Editions from Armleder to Zurier • Ross Bleckner • Dan Halter • Tess Jaray • Liza Lou • Analia Saban • and More

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2017 Volume 6, Number 6 New Editions from Armleder to Zurier • Ross Bleckner • Dan Halter • Tess Jaray • Liza Lou • Analia Saban • and more Alan Cristea Speaks with Paul Coldwell • Richard Pousette-Dart • Andrew Raferty Plates • Prix de Print • News Todd Norsten Inquiries: 612.871.1326 Monoprints [email protected] highpointprintmaking.org Todd Norsten, 2016, Untitled (Targets #6), Monoprint, 33 x 24 in. Over 25 unique works in the series, see all available at highpointprintmaking.org/project/todd-norsten-monoprints/ March – April 2017 In This Issue Volume 6, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Border Crossings Associate Publisher New Editions 2017 4 Julie Bernatz Reviews A–Z Managing Editor Alan Cristea in Conversation 28 Isabella Kendrick with Paul Coldwell Papering the World in Original Art Associate Editor Julie Warchol Exhibition Reviews Thomas Piché Jr. 33 Manuscript Editor From Tabletop to Eternity: Prudence Crowther Andrew Raftery’s Plates Editor-at-Large David Storey 36 Catherine Bindman Richard Pousette-Dart’s Flurries of Invention Design Director Skip Langer Owen Duffy 39 Leah Beeferman: Rocky Shores Prix de Print, No. 22 40 Juried by Katie Michel Aerial: Other Cities #9 by Susan Goethel Campbell News of the Print World 42 Contributors 56 Guide to Back Issues 57 On the Cover: Susan Goethel Campbell, detail of Aerial: Other Cities #9 (2015), woodblock print with perforations. Printed and published by P.R.I.N.T. Press, Denton, TX. Photo: Tim Thayer. This Page: John McDevitt King, detail of Almost There (2016), hardground etching. -

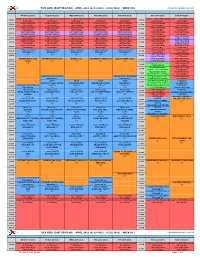

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

Robert Kennedy Historic Trail

Robert T. Kennedy, DAUFUSKIE ISLAND Founding President of the HISTORY Daufuskie Island Historical Foundation Daufuskie Island, tucked between Savannah, Georgia, and AUFUSKIE Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, was inhabited by numerous Robert T. Kennedy was born in Hartford, native tribes until the early 1700's when they were driven away D ISLAND Connecticut. Rob, a successful business man, from their land by explorers, traders and settlers. While under and his wife Dottie lived in many places British rule, plantations were developed, growing indigo and later including Hong Kong, Calcutta, New York Sea Island cotton. Slaves tilled the fields while plantation owners City, Seattle and Atlanta. They retired to and their families spent much of the year away. The slaves’ Daufuskie Island in 1991. An avid history isolation provided the setting for the retention of their African buff, Rob became a student of Daufuskie's culture. illustrious past. He served as island tour guide and became the first Plantation owners and slaves fled the island at the start of the president of the Daufuskie Island Historical Foundation when it Civil War. Union troops then occupied the island. After the war, was established in 2001. Rob was a natural raconteur and shared freed slaves (Gullah people) returned to the island, purchasing Daufuskie stories with visitors and locals alike until shortly before small plots of land or working for landowners. The boll weevil his death in 2009. destroyed the cotton fields in the early 1900's. Logging and the Rob Kennedy enjoyed a good laugh, a martini and his many Maggioni Oyster Canning Factory provided jobs for the friends.