Meeting the Challenge of Invasive Plants: a Framework for Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fauna Lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 Years Later: Changes and Additions

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (August 2000) 31 (1/2):327-367< Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 "Fauna lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 years later: changes and additions. Part 5. Noctuidae (Insecto, Lepidoptera) by Vasily V. A n ik in , Sergey A. Sachkov , Va d im V. Z o lo t u h in & A n drey V. Sv ir id o v received 24.II.2000 Summary: 630 species of the Noctuidae are listed for the modern Volgo-Ural fauna. 2 species [Mesapamea hedeni Graeser and Amphidrina amurensis Staudinger ) are noted from Europe for the first time and one more— Nycteola siculana Fuchs —from Russia. 3 species ( Catocala optata Godart , Helicoverpa obsoleta Fabricius , Pseudohadena minuta Pungeler ) are deleted from the list. Supposedly they were either erroneously determinated or incorrect noted from the region under consideration since Eversmann 's work. 289 species are recorded from the re gion in addition to Eversmann 's list. This paper is the fifth in a series of publications1 dealing with the composition of the pres ent-day fauna of noctuid-moths in the Middle Volga and the south-western Cisurals. This re gion comprises the administrative divisions of the Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara, Uljanovsk, Orenburg, Uralsk and Atyraus (= Gurjev) Districts, together with Tataria and Bash kiria. As was accepted in the first part of this series, only material reliably labelled, and cover ing the last 20 years was used for this study. The main collections are those of the authors: V. A n i k i n (Saratov and Volgograd Districts), S. -

Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States

Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States September 1993 OTA-F-565 NTIS order #PB94-107679 GPO stock #052-003-01347-9 Recommended Citation: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, Harmful Non-Indigenous Species in the United States, OTA-F-565 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, September 1993). For Sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office ii Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop, SSOP. Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN O-1 6-042075-X Foreword on-indigenous species (NIS)-----those species found beyond their natural ranges—are part and parcel of the U.S. landscape. Many are highly beneficial. Almost all U.S. crops and domesticated animals, many sport fish and aquiculture species, numerous horticultural plants, and most biologicalN control organisms have origins outside the country. A large number of NIS, however, cause significant economic, environmental, and health damage. These harmful species are the focus of this study. The total number of harmful NIS and their cumulative impacts are creating a growing burden for the country. We cannot completely stop the tide of new harmful introductions. Perfect screening, detection, and control are technically impossible and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, the Federal and State policies designed to protect us from the worst species are not safeguarding our national interests in important areas. These conclusions have a number of policy implications. First, the Nation has no real national policy on harmful introductions; the current system is piecemeal, lacking adequate rigor and comprehensiveness. Second, many Federal and State statutes, regulations, and programs are not keeping pace with new and spreading non-indigenous pests. -

1 June 2006 – Issue 1 a Newsletter for the Pyraloidea Fans

Volume 1 – 1 June 2006 – Issue 1 A newsletter for the Pyraloidea fans The Pyraloid Planet was founded on the gested the night before with great enthusi- year. The survival of The Pyraloid Planet 21st of March 2006 in Dresden, Germany asm, the name The Pyraloid Planet was depends on having interesting information by most of the participants of the first chosen by plebiscite, and quickly became to publish. This information can take GlobIZ workshop (see text below). We, in known as PP... B. Landry also proposed the form of web site announcements or order of appearance on the photograph to be the first editor, which was adopted presentations, congress announcements, below (starting from the left, Christian unanimously. The photograph below, cour- field trip accounts, observations on Schulze, Shen-Horn Yen, Andreas Segerer, tesy of Houhun Li, was taken on this mem- pyraloids, current research projects, Houhun Li, Bernard Landry, Gregor Kunert, orable occasion. advances in GlobIZ, the “Membership” Matthias Nuss, Alma Solis, and Christian list, etc. New, major publications can also The Pyraloid Planet will preferably be Schmidt) were united at the Isola bella, be announced, but shorter, new taxonomic distributed as a pdf to all those interested. an Italian restaurant in Dresden, and after papers on Pyraloidea will not be listed here Ideally, the rate of publication will be once some debate on how we should vote on the because their references will be accessible a year, and the editor will change every 15 or so possible names that we had sug- from the GlobIZ web site. Please send any Picture 1. -

A Revision of the New World Species of Donacaula Meyrick and a Phylogenetic Analysis of Related Schoenobiinae (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2010 A Revision Of The New World Species Of Donacaula Meyrick And A Phylogenetic Analysis Of Related Schoenobiinae (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) Edda Lis Martinez Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Martinez, Edda Lis, "A Revision Of The New World Species Of Donacaula Meyrick And A Phylogenetic Analysis Of Related Schoenobiinae (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 248. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/248 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A REVISION OF THE NEW WORLD SPECIES OF DONACAULA MEYRICK AND A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF RELATED SCHOENOBIINAE (LEPIDOPTERA: CRAMBIDAE) By Edda Lis Martínez A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Entomology in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Mississippi State, Mississippi December 2010 A REVISION OF THE NEW WORLD SPECIES OF DONACAULA MEYRICK AND PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF RELATED SCHOENOBIINAE (LEPIDOPTERA: CRAMBIDAE) By Edda Lis Martínez Approved: ______________________________ ______________________________ Richard -

Somerset's Ecological Network

Somerset’s Ecological Network Mapping the components of the ecological network in Somerset 2015 Report This report was produced by Michele Bowe, Eleanor Higginson, Jake Chant and Michelle Osbourn of Somerset Wildlife Trust, and Larry Burrows of Somerset County Council, with the support of Dr Kevin Watts of Forest Research. The BEETLE least-cost network model used to produce Somerset’s Ecological Network was developed by Forest Research (Watts et al, 2010). GIS data and mapping was produced with the support of Somerset Environmental Records Centre and First Ecology Somerset Wildlife Trust 34 Wellington Road Taunton TA1 5AW 01823 652 400 Email: [email protected] somersetwildlife.org Front Cover: Broadleaved woodland ecological network in East Mendip Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Policy and Legislative Background to Ecological Networks ............................................ 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 3 Government White Paper on the Natural Environment .............................................. 3 National Planning Policy Framework ......................................................................... 3 The Habitats and Birds Directives ............................................................................. 4 The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 .................................. -

Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 This Blue Goose, Designed by J.N

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 This blue goose, designed by J.N. “Ding” Darling, has become the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is the principal federal agency responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fi sh, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefi t of the American people. The Service manages the 97-million acre National Wildlife Refuge System comprised of more than 548 national wildlife refuges and thousands of waterfowl production areas. It also operates 69 national fi sh hatcheries and 81 ecological services fi eld stations. The agency enforces federal wildlife laws, manages migratory bird populations, restores nationally signifi cant fi sheries, conserves and restores wildlife habitat such as wetlands, administers the Endangered Species Act, and helps foreign governments with their conservation efforts. It also oversees the Federal Assistance Program which distributes hundreds of millions of dollars in excise taxes on fi shing and hunting equipment to state wildlife agencies. Comprehensive Conservation Plans provide long term guidance for management decisions and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes and identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program planning levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. The plans do not constitute a commitment for staffi ng increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan February 2009 Submitted by: Edward Henry Date Refuge Manager Wallkill River National Wildlife Refuge Concurrence by: Janet M. -

Zoogeography of the Holarctic Species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): Importance of the Bering Ian Refuge

© Entomologica Fennica. 8.XI.l991 Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Bering ian refuge Kauri Mikkola, J, D. Lafontaine & V. S. Kononenko Mikkola, K., Lafontaine, J.D. & Kononenko, V. S. 1991 : Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Beringian refuge. - En to mol. Fennica 2: 157- 173. As a result of published and unpublished revisionary work, literature compi lation and expeditions to the Beringian area, 98 species of the Noctuidae are listed as Holarctic and grouped according to their taxonomic and distributional history. Of the 44 species considered to be "naturall y" Holarctic before this study, 27 (61 %) are confirmed as Holarctic; 16 species are added on account of range extensions and 29 because of changes in their taxonomic status; 17 taxa are deleted from the Holarctic list. This brings the total of the group to 72 species. Thirteen species are considered to be introduced by man from Europe, a further eight to have been transported by man in the subtropical areas, and five migrant species, three of them of Neotropical origin, may have been assisted by man. The m~jority of the "naturally" Holarctic species are associated with tundra habitats. The species of dry tundra are frequently endemic to Beringia. In the taiga zone, most Holarctic connections consist of Palaearctic/ Nearctic species pairs. The proportion ofHolarctic species decreases from 100 % in the High Arctic to between 40 and 75 % in Beringia and the northern taiga zone, and from between 10 and 20 % in Newfoundland and Finland to between 2 and 4 % in southern Ontario, Central Europe, Spain and Primorye. -

Downloaded from BOLD Or Requested from Other Authors

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Towards a global DNA barcode reference library for quarantine identifcations of lepidopteran Received: 28 November 2018 Accepted: 5 April 2019 stemborers, with an emphasis on Published: xx xx xxxx sugarcane pests Timothy R. C. Lee 1, Stacey J. Anderson2, Lucy T. T. Tran-Nguyen3, Nader Sallam4, Bruno P. Le Ru5,6, Desmond Conlong7,8, Kevin Powell 9, Andrew Ward10 & Andrew Mitchell1 Lepidopteran stemborers are among the most damaging agricultural pests worldwide, able to reduce crop yields by up to 40%. Sugarcane is the world’s most prolifc crop, and several stemborer species from the families Noctuidae, Tortricidae, Crambidae and Pyralidae attack sugarcane. Australia is currently free of the most damaging stemborers, but biosecurity eforts are hampered by the difculty in morphologically distinguishing stemborer species. Here we assess the utility of DNA barcoding in identifying stemborer pest species. We review the current state of the COI barcode sequence library for sugarcane stemborers, assembling a dataset of 1297 sequences from 64 species. Sequences were from specimens collected and identifed in this study, downloaded from BOLD or requested from other authors. We performed species delimitation analyses to assess species diversity and the efectiveness of barcoding in this group. Seven species exhibited <0.03 K2P interspecifc diversity, indicating that diagnostic barcoding will work well in most of the studied taxa. We identifed 24 instances of identifcation errors in the online database, which has hampered unambiguous stemborer identifcation using barcodes. Instances of very high within-species diversity indicate that nuclear markers (e.g. 18S, 28S) and additional morphological data (genitalia dissection of all lineages) are needed to confrm species boundaries. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

Botolph's Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West And

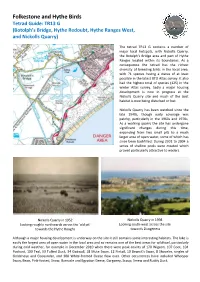

Folkestone and Hythe Birds Tetrad Guide: TR13 G (Botolph’s Bridge, Hythe Redoubt, Hythe Ranges West, and Nickolls Quarry) The tetrad TR13 G contains a number of major local hotspots, with Nickolls Quarry, the Botolph’s Bridge area and part of Hythe Ranges located within its boundaries. As a consequence the tetrad has the richest diversity of breeding birds in the local area, with 71 species having a status of at least possible in the latest BTO Atlas survey. It also had the highest total of species (125) in the winter Atlas survey. Sadly a major housing development is now in progress at the Nickolls Quarry site and much of the best habitat is now being disturbed or lost. Nickolls Quarry has been watched since the late 1940s, though early coverage was patchy, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. As a working quarry the site has undergone significant changes during this time, expanding from two small pits to a much larger area of open water, some of which has since been backfilled. During 2001 to 2004 a series of shallow pools were created which proved particularly attractive to waders. Nickolls Quarry in 1952 Nickolls Quarry in 1998 Looking roughly northwards across the 'old pit' Looking south-west across the site towards the Hythe Roughs towards Dungeness Although a major housing development is underway on the site it still contains some interesting habitats. The lake is easily the largest area of open water in the local area and so remains one of the best areas for wildfowl, particularly during cold weather, for example in December 2010 when there were peak counts of 170 Wigeon, 107 Coot, 104 Pochard, 100 Teal, 53 Tufted Duck, 34 Gadwall, 18 Mute Swan, 12 Pintail, 10 Bewick’s Swan, 8 Shoveler, singles of Goldeneye and Goosander, and 300 White-fronted Geese flew over. -

Database of Irish Lepidoptera. 1 - Macrohabitats, Microsites and Traits of Noctuidae and Butterflies

Database of Irish Lepidoptera. 1 - Macrohabitats, microsites and traits of Noctuidae and butterflies Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 35 Database of Irish Lepidoptera. 1 - Macrohabitats, microsites and traits of Noctuidae and butterflies Ken G.M. Bond and Tom Gittings Department of Zoology, Ecology and Plant Science University College Cork Citation: Bond, K.G.M. and Gittings, T. (2008) Database of Irish Lepidoptera. 1 - Macrohabitats, microsites and traits of Noctuidae and butterflies. Irish Wildlife Manual s, No. 35. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Cover photo: Merveille du Jour ( Dichonia aprilina ) © Veronica French Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: F. Marnell & N. Kingston © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2008 ISSN 1393 – 6670 Database of Irish Lepidoptera ____________________________ CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................2 The concept of the database.....................................................................................................................2 The structure of the database...................................................................................................................2 -

1-Embacher Band 10.Indd

©Österr. Ges. f. Entomofaunistik, Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Beiträge zur Entomofaunistik 10 3-15 Wien, Dezember 2009 Die Crambidae (Lepidoptera) des Landes Salzburg, Österreich Gernot Embacher* Abstract The Crambidae (Lepidoptera) of the province Salzburg, Austria. The present paper deals with the species of Crambidae of the Austrian province of Salzburg. MITTERBERGER (1909) lists 77 species while today 118 species are recorded for the fauna of Salzburg. Five species listed in HUEMER & TARMANN (1993) must be removed, another 11 species are new to the fauna of Salzburg. The occurrence of one out of two species in HUEMER & TARMANN (1993) provided with a question mark is confirmed. Keywords: Lepidoptera, Crambidae, Austria, Salzburg, entomological literature, faunistic records, collection „Haus der Natur“. Zusammenfassung Diese Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit den Crambidae des Landes Salzburg (Österreich). Während in MITTERBERGER (1909) 77 Arten für Salzburgs Fauna aufgelistet sind, gelten derzeit 118 Spezies als nachgewiesen. Aus der Liste von HUEMER & TARMANN (1993) müssen fünf Arten ausgeschieden wer- den, während elf Arten als neu für die Fauna Salzburgs hinzu kommen. Das Vorkommen einer von zwei in HUEMER & TARMANN (1993) mit einem Fragezeichen versehenen Arten konnte bestätigt werden. Einleitung Die Serie von Berichten über die Salzburger Mikrolepidopterenfauna wird mit dem aktuellen Bearbeitungsstand der Familie Crambidae fortgesetzt (Scopariinae, Crambinae, Schoenobiinae, Odontiinae, Evergestinae, Cathariinae und Pyraustinae). Während in einer ersten Arbeit über die Salzburger Pyralioidea (EMBACHER 1998) die Verbreitung der Arten in den Salzburger Landesteilen im Mittelpunkt stand, sollen hier neben Ergänzungen und Berichtigungen auch alle dem Autor bekannten Literaturangaben aufgeführt werden, die Informationen über die Arten der Familie Crambidae enthalten.