Transit and Shopping Centers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 FINALISTS ICSC Is Proud to Announce the Finalists of the 2012 U.S

2012 FINALISTS ICSC is proud to announce the finalists of the 2012 U.S. MAXI Awards. The U.S. MAXI Awards honor outstanding marketing campaigns from all over the United States. Chosen by a panel of industry professionals, these finalists represent excellence throughout the industry. The 2012 U.S. Maxi Awards will be presented at ICSC’s first-ever NOI + Conference in Orlando, Florida, September 5, 2012. TRADITIONAL MARKETING - ADVERTISING Single Center Pooches Pose at The Brickyard’s PUParazzi! The Brickyard Shopping Center Chicago, Illinois Owner: Retail Properties of America, Inc. Management Company: RPAI US Management, LLC The Gateway provides Daily Dish The Gateway Salt Lake City, Utah Owner: Retail Properties of America, Inc. Management Company: RPAI, Southwest Management Favorite Label Consumer Campaign Natick Mall Natick, Massachusetts Owner/Management Company: General Growth Properties Home for the Holidays Promotional Campaign Southlake Town Square Southlake, Texas Owner: Retail Properties of America Inc Management Company: RPAI Southwest Management LLC Company 2011 Hillsdale’s South End Renovation Bohannon Development Company San Mateo, California MORE Holiday Advertising CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. Chattanooga, Tennessee Joint Center Club Estrellas E-Magazine The Shops at La Cantera and North Star Mall San Antonio, Texas Management Company: General Growth Properties TRADITIONAL MARKETING - BUSINESS-TO-BUSINESS (B2B) Single Center The Writing’s on the Wall West Acres Shopping Center Fargo, North Dakota Owner/Management Company: West Acres Development, LLP Company Think Retail. Create Value. DDR Corp. Beachwood, Ohio Keep The Dollars In Dallas United Commercial Realty Dallas, Texas TRADITIONAL MARKETING - CAUSE RELATED MARKETING Single Center Queen for a Day Aspen Grove Littleton, Colorado Owner/Management Company: DDR Corp. -

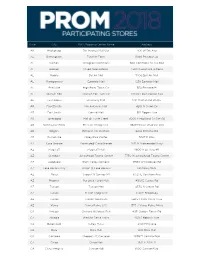

Prom 2018 Event Store List 1.17.18

State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address AK Anchorage 5th Avenue Mall-Sur 406 W 5th Ave AL Birmingham Tutwiler Farm 5060 Pinnacle Sq AL Dothan Wiregrass Commons 900 Commons Dr Ste 900 AL Hoover Riverchase Galleria 2300 Riverchase Galleria AL Mobile Bel Air Mall 3400 Bell Air Mall AL Montgomery Eastdale Mall 1236 Eastdale Mall AL Prattville High Point Town Ctr 550 Pinnacle Pl AL Spanish Fort Spanish Fort Twn Ctr 22500 Town Center Ave AL Tuscaloosa University Mall 1701 Macfarland Blvd E AR Fayetteville Nw Arkansas Mall 4201 N Shiloh Dr AR Fort Smith Central Mall 5111 Rogers Ave AR Jonesboro Mall @ Turtle Creek 3000 E Highland Dr Ste 516 AR North Little Rock Mc Cain Shopg Cntr 3929 Mccain Blvd Ste 500 AR Rogers Pinnacle Hlls Promde 2202 Bellview Rd AR Russellville Valley Park Center 3057 E Main AZ Casa Grande Promnde@ Casa Grande 1041 N Promenade Pkwy AZ Flagstaff Flagstaff Mall 4600 N Us Hwy 89 AZ Glendale Arrowhead Towne Center 7750 W Arrowhead Towne Center AZ Goodyear Palm Valley Cornerst 13333 W Mcdowell Rd AZ Lake Havasu City Shops @ Lake Havasu 5651 Hwy 95 N AZ Mesa Superst'N Springs Ml 6525 E Southern Ave AZ Phoenix Paradise Valley Mall 4510 E Cactus Rd AZ Tucson Tucson Mall 4530 N Oracle Rd AZ Tucson El Con Shpg Cntr 3501 E Broadway AZ Tucson Tucson Spectrum 5265 S Calle Santa Cruz AZ Yuma Yuma Palms S/C 1375 S Yuma Palms Pkwy CA Antioch Orchard @Slatten Rch 4951 Slatten Ranch Rd CA Arcadia Westfld Santa Anita 400 S Baldwin Ave CA Bakersfield Valley Plaza 2501 Ming Ave CA Brea Brea Mall 400 Brea Mall CA Carlsbad Shoppes At Carlsbad -

Generalgrowthproperties

BUILT TO LEAD BUILT TO GROW BUILT TO PROSPER GENERALGROWTHBUILT PROPERTIES TO LASTANNUAL REPORT 2002 COMPANY PROFILE General Growth Properties and its predecessor companies have been in the shopping center busi- ness for nearly fifty years. It is the second largest regional mall Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) in the United States. General Growth owns, develops, operates and/or manages shopping malls in 39 states. GGP has ownership interests in, or management responsibility for, 160 regional shopping malls totaling more than 140 million square feet of retail space. The total retail space is inclusive of more than 16,000 retailers nationwide. General Growth provides investors with the opportunity to participate in the ownership of high-quality, income-producing real estate while maintaining liquidity. Our primary objective is to provide increasing dividends and capital appreciation for our shareholders. Creating shareholder value is the company’s mission. The Bucksbaum family, which founded General Growth, is still engaged in the operation of the company’s day-to-day business activities. As owners of a major stake in the company, General Growth management’s interests are aligned with those of each and every GGP shareholder. CONTENTS Shareholders’ Letter 4 Operating Principles 7 Portfolio 17 Financial Review 29 Directors and Officers 85 Corporate Information 86 Financial Highlights SHOPPING CENTERS OWNED at year end * 1997 64 1998 84 1999 93 2000 95 2001 97 2002 125 TOTAL SQUARE FOOTAGE OWNED in millions 1997 52 1998 71 1999 83 2000 85 2001 89 2002 114 REAL ESTATE ASSETS AT COST in millions 1997 $2,590 1998 $4,760 1999 $6,237 2000 $6,735 2001 $7,319 2002 $9,902 MALL SHOP SALES in millions ** 1997 $2,651 1998 $5,176 1999 $6,931 2000 $7,243 2001 $7,326 2002 $9,061 DIVIDEND GROWTH PER SHARE dollar/share declared 1997 $1.80 1998 $1.88 1999 $1.98 2000 $2.06 2001 $2.36 2002 $2.74 FFO GROWTH dollar/share 1997 $2.89 1998 $3.35 1999 $4.02 2000 $4.42 2001 $4.96 2002 $5.58 * Includes regional malls only. -

Phase I Environmental Site Assessment Location Westfield Valley Fair Expansion Stevens Creek Boulevard Santa Clara and San Jose, California

Type of Services Phase I Environmental Site Assessment Location Westfield Valley Fair Expansion Stevens Creek Boulevard Santa Clara and San Jose, California Client David J. Powers & Associates Client Address 1871 The Alameda, Suite 200 San Jose, California 95126 Project Number 118-39-1 Date January 21, 2013 Prepared by Stason I. Foster, P.E. Senior Project Engineer Ron L. Helm, C.E.G., C.Hg. Senior Principal Geologist Table of Contents SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 SCOPE OF WORK ................................................................................................ 2 1.3 ASSUMPTIONS .................................................................................................... 2 1.4 ENVIRONMENTAL PROFESSIONAL .................................................................. 2 SECTION 2: SITE DESCRIPTION .................................................................................. 2 2.1 SITE LOCATION, CURRENT USES AND OWNERSHIP ...................................... 3 2.3 SITE SETTING AND ADJOINING SITE USE ........................................................ 4 SECTION 3: USER PROVIDED INFORMATION ............................................................ 4 3.1 CHAIN OF TITLE .................................................................................................. 4 3.2 ENVIRONMENTAL LIENS OR -

Pirates Theaters 010308

The Pirates Who Don't Do Anything - A VeggieTales Movie - - - In Theaters January 11th Please note: This list is current as of January 3, 2008 and is subject to change. Additional theaters are being added over the next few days, so be sure to check back later for an updated list. To arrange for group ticket sales, please call 1-888-863-8564. Thanks for your support and we'll see you at the movies! Theater Address City ST Zip Code Sunridge Spectrum Cinemas 400-2555 32nd Street NE Calgary AB(CAN) T1Y 7X3 Scotiabank Theatre Chinook (formerly Paramoun 6455 Macleod Trail S.W. Calgary AB(CAN) T2H 0K4 Empire Studio 16 Country Hills 388 Country Hills Blvd., N.E. Calgary AB(CAN) T3K 5J6 North Edmonton Cinemas 14231 137th Avenue NW Edmonton AB(CAN) T5L 5E8 Clareview Clareview Town Centre Edmonton AB(CAN) T5Y 2W8 South Edmonton Common Cinemas 1525-99th Street NW Edmonton AB(CAN) T6N 1K5 Lyric 11801 100th St. Grande Prairie AB(CAN) T8V 3Y2 Galaxy Cinemas Lethbridge 501 1st. Ave. S.W. Lethbridge AB(CAN) T1J 4L9 Uptown 4922-49th Street Red Deer AB(CAN) T4N 1V3 Parkland 7 Cinemas 130 Century Crossing Spruce Grove AB(CAN) T7X 0C8 Dimond Center 9 Cinemas 800 Dimond Boulevard Anchorage AK 99515 Goldstream Stadium 16 1855 Airport Road Fairbanks AK 99701 Grand 14 820 Colonial Promenade Parkway Alabaster AL 35007 Cinemagic Indoor 1702 South Jefferson Street Athens AL 35611 Wynnsong 16-Auburn 2111 East University Drive Auburn AL 36831 Trussville Stadium 16 Colonial Promenade Shopping Center Birmingham AL 35235 Lee Branch 15 801 Doug Baker Blvd. -

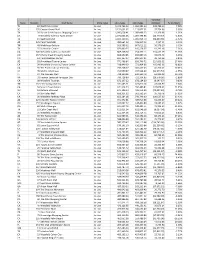

State Storeno Mall Name Store Type 2015 Sales 2014 Sales Variance

Variance State StoreNo Mall Name Store Type 2015 Sales 2014 Sales Inc/(Dec) % Inc/(Dec) TX 83 NorthPark Center In-Line 1,472,766.00 1,363,984.00 108,782.00 7.98% SC 135 Coastal Grand Mall In-Line 1,151,631.67 1,113,877.31 37,754.36 3.39% TX 20 Barton Creek Square Shopping Center In-Line 1,096,658.41 1,083,499.33 13,159.08 1.21% CA 8 Westfield Valencia Town Center In-Line 1,071,022.26 1,087,795.83 (16,773.57) -1.54% TX 19 Baybrook Mall In-Line 1,025,120.43 1,055,953.79 (30,833.36) -2.92% AZ 125 Park Place Mall In-Line 950,664.23 946,527.12 4,137.11 0.44% TN 48 Wolfchase Galleria In-Line 923,588.32 867,012.22 56,576.10 6.53% TX 55 Stonebriar Centre In-Line 876,800.55 815,558.37 61,242.18 7.51% CA 126 Westfield Galleria at Roseville In-Line 869,168.30 754,757.11 114,411.19 15.16% CO 167 Cherry Creek Shopping Center In-Line 868,959.85 835,887.13 33,072.72 3.96% CO 61 Park Meadows Center In-Line 831,157.07 800,397.91 30,759.16 3.84% AZ 28 Arrowhead Towne Center In-Line 771,406.64 656,746.72 114,659.92 17.46% CA 39 Westfield University Towne Center In-Line 738,949.33 573,464.00 165,485.33 28.86% CA 35 The Promenade at Temecula In-Line 733,268.27 666,557.65 66,710.62 10.01% KY 78 Mall St. -

Desert Fashion Plaza Property Condition Report and Phase I Environmental Assessment

.,.,. .r.-· ~ Building Diagnostics, Ltd. DESERT FASHION PLAZA PROPERTY CONDITION REPORT AND PHASE I ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT t'7;38 Elton Road Sbite 318 Silver Spring, MD 20903 The Property Condition Report & BDL Phase I Environmental Site Assessment for: . I Property Name DESERT FASHION PLAZA~ Property Address 123 North Canyon Drive Palm Springs, California 92262 Report Number 8-o1-o1o 11 Prepared for EXCEL LEGACY CORPORATION, its successors and/or assigns Gateway Tower, 563 West 500 South Suite 440 Woods Cross, Utah 84087 Prepared by BUILDING DIAGNOSTICS, L TO 1738 Elton Road, Suite 318 Silver Spring, Maryland 20903 301 408 2552 Evaluation Date · . January 19, 1998\\ Report Date January 23, 1998\\ .. Table of Contents Section Page Topic .I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 #3 • Rapid Review .....I I .. I 2 #9 • Scope of Work I SITE OVERVIEW I 3 #16 • Subject Property Description I j PROPERTY CONDITION REPORT I 4 #19 • Site and Common Elements I I 5 #24 • Architectural I 6 #28 • Mechanical and Electrical Systems 7 #34 • Photographs I 8 #40 • Americans with Disabilities Act I I PHASE I ENVIRONMENTAL SITE ASSESSMENT I 9 #41 • Site Reconnaissance I 10 #54 • Records and Database Review I 11 #79 • Information Sources 12 #80 • Appendixes I © 1998 Building Diagnostics, Ltd. 2 Desert Fashion Plaza Executive Summary ' 8-01,D10. 1/19198 Rapid Review I SECTION 1 RAPID REVIEW~ SUMMARY II These charts present a summary only. Please refer to the I pages listed for comprehensive information about each _ item listed. b=================~ CONDmON The designations "good", "fair", and "poor'' are defined as DESIGNA110N follows: "Good" means that the item is in average or better condition for its age, use and location of the property. -

Anaheim.Qxp Layout 1 4/26/19 11:09 AM Page 45

City_of_Anaheim.qxp_Layout 1 4/26/19 11:09 AM Page 45 CUSTOM CONTENT • April 29, 2019 Presented By City_of_Anaheim.qxp_Layout 1 4/26/19 11:10 AM Page 46 C-46 ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL CITY OF ANAHEIM APRIL 29, 2019 City_of_Anaheim.qxp_Layout 1 4/26/19 11:10 AM Page 47 APRIL 29, 2019 CITY OF ANAHEIM ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL C-47 City_of_Anaheim.qxp_Layout 1 4/26/19 11:10 AM Page 48 C-48 ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL CITY OF ANAHEIM APRIL 29, 2019 City_of_Anaheim.qxp_Layout 1 4/26/19 11:11 AM Page 49 City_of_Anaheim.qxp_Layout 1 4/26/19 11:11 AM Page 50 C-50 ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL CITY OF ANAHEIM APRIL 29, 2019 Anaheim Based Firm Wincome USA Rebrands Its Management Division as Wincome Hospitality Wincome USA, a privately owned real-estate investment, development and but now under Marriott’s portfolio). Attributed with multiple awards, including Marriott’s management firm, based in Anaheim, California, announces this week their intent to Franchise Hotel of the Year Award for Distinctive Properties in both 2017 and 2018 for launch Wincome Hospitality, their new hospitality division. With nearly 40 years in the Avenue of the Arts Costa Mesa Hotel, Wincome was able to take another forgotten industry successfully managing multiple hotels and restaurants, Wincome has property and turn it into a market leader. elevated every project and establishment to greater levels of quality and profitability. Their new hospitality division plans to do more of that. In 2016, Wincome purchased an office building at 888 Disneyland Drive—leasing the building to tenants as well as setting up their corporate headquarters. -

350-420 Palm Canyon

FOR SALE | PRIME DOWNTOWN PALM SPRINGS ASSEMBLAGE 350-420 PA L M C A N Y O N PALM SPRINGS, CA 188,179 SF (4.32 ACRES) DEVELOPMENT SITE +/- 1,300 FEET OF FRONTAGE ON PALM CANYON AND INDIAN DRIVES SOUTH BELERADO ROAD SOUTH PALM CANYON DRIVE WEST RAMON ROAD SOUTH INDIAN CANYON DRIVE TIMOTHY L BOWER MARCO ROSSETTI GABRIELLE LARDIERE Senior Vice President Senior Associate +1 310 550 2605 +1 310 550 2521 +1 760 578 4723 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Lic. 01911073 Lic. 00864693 Lic. 01805951 CAPITAL MARKETS TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Investment Summary Investment Highlights AERIAL OVERVIEW THE PROPERTY Current Improvements Site Plan MARKET OVERVIEW Regional Overview | Coachella Valley Submarket Overview | City of Palm Springs APPENDIX Zoning Code Palm Springs, CA WEST ARENAS ROAD SITE SOUTH BELERADO ROAD SOUTH PALM CANYON DRIVE SOUTH INDIAN CANYON DRIVE WEST RAMON ROAD N EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Investment Summary Investment Highlights EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INVESTMENT SUMMARY CBRE has been retained on an exclusive basis to present the opportunity to acquire an unequaled investment/mixed-use development site at the Southern Gateway to Palm Springs’ resurgent Downtown commercial core. The site currently consists of 4 parcels of land totaling approximately 188,500 square feet (4.32 acres) with 1,300 feet of combined frontage along Palm Canyon and Indian Drives. This prime site has potential for retail, office and residential development, and boasts spectacular street front visibility as well as mountain and Coachella Valley views. The site offers interim cash flow to an investor, with retail tenants such as Rite Aid and BBVA Compass Bank. -

Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 148 / Friday, August 1, 1997 / Notice

41492 Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 148 / Friday, August 1, 1997 / Notice FEDERAL EMERGENCY of public accommodation. The law compiling listings of properties that MANAGEMENT AGENCY encourages and eventually mandates comply with the Hotel and Motel Fire that federal employees on travel must Safety Act. A list of State contacts was Hotel and Motel Fire Safety Act stay in public accommodations that published in 58 FR 17020 on March 31, National Master List, 1997 adhere to the life safety requirements in 1993, 59 FR 50132 on September 30, the legislation guidelines. Similarly, AGENCY: United States Fire 1994, 59 FR 62174 on December 2, 1994, Administration, FEMA. federally sponsored or funded and 61 FR 32032 on June 21, 1996. The conferences cannot be held in hotels most recent list of State contacts is ACTION: Notice. and motels or other facilities that do not published as a separate part with this SUMMARY: The Federal Emergency meet the law's fire protection issue of the Federal Register. If the Management Agency (FEMA or Agency) provisions. published list is unavailable to you, gives notice of the national master list The legislation gives hotels, motels, your State Fire Marshal's office can of places of public accommodations that and other facilities an economic direct you to the appropriate office. incentive to install lifesaving smoke meet the fire prevention and control Copies of the national master list and detectors and automatic sprinkler guidelines under the Hotel and Motel its updates may be obtained by writing systems. A hotel or motel or other Fire Safety Act. This updated list to the Government Printing Office, facility that complies with the fire safety incorporates all changes made to the Superintendent of Documents, national master list since it was first guidelines of the Act will be included in federal travel directories and have the Washington, DC 20402±9325. -

Englewood Citycenter Edition

TO: Mayor Olsen and Council Members THRU: Brad Power, Community Development Director FROM: Wade Burkholder, Planning Manager John Voboril, Senior Planner Erik Sampson, Planner II DATE: January 20, 2019 SUBJECT: Upcoming Community Development Public Meetings The Community Development Department would like to announce several upcoming facilitated community meetings. On March 21, 2019 from 6:30 - 8:30 P .M. in Hampden Hall, the City will host residents of the Neighborhood Preservation Overlay (NPO) to discuss how Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU) will affect this overlay district. Passage of the ADU Ordinance included a six (6) month temporary moratorium on the approval of applications forADU's and any associated building permits to provide for additional time to review and determine the specific issues associated with allowing ADU's within the NPO District. Each resident of the NPO area will receivea direct mailing announcing the meeting. Residents can discuss with Staffwhat the NPO regulates and how ADU's interact with the legislation that created the District. On Tuesday April 2, 2019 from 6:00 - 9:00 PM in the Community Room, the City of Englewood will host Staff from the City/County of Denver, City of Lakewood, and the City of Golden to discuss short-term rental regulations collectively within the Metro Denver region. Each community will provide a short presentation on how short term rentals have affected their communities. Audience members will then be able to ask questions related to short-term rentals and the sharing economy. Citizens, elected and appointed officials from any jurisdiction are welcome to attend the town hall to ask questions of the panel. -

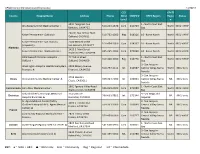

CPQCC HRIF Directory NOV2018

CPQCC Center Directory Listed by County 12/10/18 CCS CPeTS County Hospital Name Address Phone NICU OSHPD # RPPC Region Regio Status Level n 3011 Telegraph Ave 1 - North Coast East Alta Bates Summit Medical Center ● 510-204-1648 Com 010739 North NICU + HRIF BerKeley, CA 94705 Bay 280 W. Mac Arthur Blvd. Kaiser Permanente - OaKland ● 510-752-1000 Reg 014326 10 - Kaiser North North NICU + HRIF OaKland, CA 94611 Kaiser Permanente - San Leandro 2500 Merced Street 510-454-1000 Com 014337 10 - Kaiser North North NICU + HRIF (Hayward) ● San Leandro, CA 94577 Alameda 1425 S. Main Street Kaiser Permanente - Walnut CreeK ● 925-295-4000 Com 070990 10 - Kaiser North North NICU + HRIF Walnut CreeK, CA 94598 UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital - 747 52nd Street 1 - North Coast East 510-428-3000 Reg 010776 North NICU + HRIF OaKland ● OaKland, CA 94609 Bay 3 - San Joaquin- Washington Hospital Healthcare System - 2000 Mowry Avenue 510-797-1111 Int 010987 Central Valley-Sierra North NICU only Fremont ▲ Fremont, CA 94538 Nevada 3 - San Joaquin- 2755 Hendon Clovis Clovis Community Medical Center ▲ 559-324-4000 Int 100005 Central Valley-Sierra NA NICU only Clovis, CA 93611 Nevada 1601 Ygnacio Valley Road 1 - North Coast East Contra Costa John Muir Medical Center ● 925-939-3000 Com 070988 North NICU + HRIF Walnut CreeK, CA 94598 Bay Rady Children's at Scripps Memorial 354 Santa Fe 9 - San Diego and Encinitas 760-633-7801 Int 371394 NA NICU only Hospital Encinitas ▲ Encinitas, CA 92024 Imperial St. Agnes Medical Center (Valley 3 - San Joaquin- 1303 E. Herdon Ave.