Big Book of How To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Self-Publishing Best Practices

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Fall 2019 Book Self-Publishing Best Practices Erica Jansma Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Communication Commons Book Self-Publishing Best Practices by Erica Jansma A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of M.S. Technical Communication Montana Tech 2019 ii Abstract I have taken a manuscript through the book publishing process to produce a camera-ready print book and e-book. This includes copyediting, designing layout templates, laying out the document in InDesign, and producing an index. My research is focused on the best practices and standards for publishing. Lessons learned from my research and experience include layout best practices, particularly linespacing and alignment guidelines, as well as the limitations and capabilities of InDesign, particularly its endnote functionality. Based on the results of this project, I can recommend self-publishers to understand the software and distribution platforms prior to publishing a book to ensure the required specifications are met to avoid complications later in the process. This document provides details on many of the software, distribution, and design options available for self-publishers to consider. Keywords: self-publishing, publishing, books, ebooks, book design, layout iii Dedication I dedicate this project to both of my grandmothers. I grew up watching you work hard, sacrifice, trust, and love with everything you have; it was beautiful; you are beautiful; and I hope I can model your example with a fraction of your grace and fruitfulness. Thank you for loving me so well. -

The Smashwords Book Marketing Guide

The Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Copyright 2008-2012 Mark Coker, Founder of Smashwords (http://www.smashwords.com) Version 1.18 Updated 12.9.12 ~~**~~ Smashwords Edition Cover design by PJ Lyon ~~**~~ Other Smashwords Titles by Mark Coker: The Smashwords Style Guide (how to format an ebook) The Secrets to Ebook Publishing Success (ebook publishing best practices) The 10-Minute PR Checklist – How to Earn the Publicity You Deserve Boob Tube (novel about Hollywood celebrity) ~~**~~ Table of Contents Introduction: About the Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Background on Smashwords Setting expectations How Smashwords helps authors and publishers market books Adopting a proactive marketing mindset Marketing starts now Hyperlinks help readers discover books The importance of authors helping authors 37 Marketing Tips (all free to implement!) Tip #1 – Update your email signature Tip #2 – Post a notice on your web site or blog Tip #3 – Contact your friends, family, co-workers and fans Tip #4 – Post a notice to your social networks Tip #5 – Update your message board signatures Tip #6 – How to reach readers with Twitter Tip #7 – Publish more than one book to create a multiplier effect Tip #8 – Advertise your other books in each book you publish Tip #9 – Make it easy for your readers to connect with you Tip #10 – Issue a press release on a free PR wire service Tip #11 – Join HARO, Help-a-reporter-online for free press leads Tip #12 – Encourage fans to purchase and review your book Tip #13 – Write thoughtful reviews for other books Tip #14 – Participate -

Writing Brave and Free : Encouraging Words for People Who Want to Start

TE D KOOSER & St EV E C O X Writing Brave & Free Encouraging Words for People Who Want to Start Writing 1 2 3 WRITING BRAVE AND FREE 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 [First Page] 12 13 [-1], (1) 14 15 Lines: 0 to 43 16 17 ——— 18 * 429.44899pt PgVar ——— 19 Normal Page 20 * PgEnds: PageBreak 21 22 23 [-1], (1) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Kim — University of Nebraska Press / Page i / / Writing Brave and Free / Ted Kooser and Steve Cox 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 [-2], (2) 14 15 Lines: 43 to 54 16 17 ——— 18 * 468.0pt PgVar ——— 19 Normal Page 20 * PgEnds: PageBreak 21 22 23 [-2], (2) 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Kim — University of Nebraska Press / Page ii / / Writing Brave and Free / Ted Kooser and Steve Cox 1 2 3 TED KOOSER & STEVE COX 4 5 6 7 8 9 Writing 10 11 12 13 [-3], (3) 14 15 Brave Lines: 54 to 107 16 17 ——— 18 11.666pt PgVar ——— 19 Normal Page 20 and Free * PgEnds: PageBreak 21 22 23 [-3], (3) 24 Encouraging Words for 25 26 People Who Want to 27 28 29 Start Writing 30 31 32 33 34 35 UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS LINCOLN & LONDON 36 37 Kim — University of Nebraska Press / Page iii / / Writing Brave and Free / Ted Kooser and Steve Cox 1 “Vision by Sweetwater” 2 from Selected Poems, 3rd ed., revised and enlarged 3 by John Crowe Ransom, 4 © 1924, 1927 by 5 Alfred A. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

PDF Download Mag Men : Fifty Years of Making Magazines Ebook, Epub

MAG MEN : FIFTY YEARS OF MAKING MAGAZINES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Walter Bernard | 288 pages | 31 Dec 2019 | Columbia University Press | 9780231191807 | English | New York, United States Mag Men : Fifty Years of Making Magazines PDF Book HuffPost Personal Video Horoscopes. FB Tweet ellipsis More. I am a stress eater and holiday time is my trigger. About Blog Life Begins At Magazine is the ultimate lifestyle publication for those who are retired, semi-retired or approaching retirement. Some skew toward men's fashion, others to health. Predicting the 3D shape of a protein purely from its genetic sequence is a complex task. Calmly and efficiently it took them ten minutes to maneuver my bed, my IV, and all my belongings thrown on top of the blanket, through silent hallways and down two elevators to my new room. The French ruled the early days of pornography publishing, distributing programs for Parisian cabarets adorned with topless dancers as early as the s. I couldn't have done this without you. Bernard and Glaser revolutionized the look of magazines, and in the process they reinvigorated the art of visual storytelling. While some Americans attempted to import racy material from Europe, the industry was blunted in the U. The Men's Health Home Gym Awards Our editors picked this year's top gear for your personal workout space, and even got a few tips from new Walker star and home gym hero…. By Vanessa Powell. The beginning of her career was mired by racial prejudice, but she soon found great success and went on to model until , before becoming a businesswoman and prominent voice in the black women's beauty industry. -

Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Copyright 2008-2020 Mark

Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Copyright 2008-2020 Mark Coker, Founder of Smashwords (http://www.smashwords.com) Version 2.5 Rev 12.19.19 ~~**~~ Smashwords Edition Cover design by PJ Lyon ~~**~~ Other Books by Mark Coker: Smashwords Style Guide (How to format and publish an ebook) Secrets to Ebook Publishing Success (Ebook publishing best practices) 10-Minute PR Checklist – (How to Earn the Publicity You Deserve Boob Tube (Novel about Hollywood celebrity) ~~**~~ Table of Contents Introduction About the Smashwords Book Marketing Guide Why I wrote this book What is book marketing? Writing is marketing The rise of ebooks The competitive advantage of indie ebook authors Setting expectations Chapter 1. The Free Book Marketing Tools at Smashwords 1. Distribution to retailers and libraries 2. The Smashwords Store 3. Smashwords Presales 4. Global Pricing Control 5. Daily Sales reporting 6. Multiple ebook file types 7. Author profile pages 8. Book pages 9. Book sampling 10. Smart shopping cart 11. Book reviews 12. Coupons! 13. Promotional widgets 14. Search engine visibility 15. Exclusive “Special Deals” promotions 16. Smashwords Interviews 17. Embeddable YouTube videos 18. Book tagging 19. Tag cloud 20. Other books by this author or publisher 21. Integration with social media sites 22. Smashwords Affiliate Partners program 23. Exclusive site-wide promotions 24. Promotion on Smashwords Satellites 25. Access to retailer merchandising promotions 26. Free author education resources Chapter 2. 66 MARKETING TIPS FOUNDATION -BUILDING Author Brand-Building -

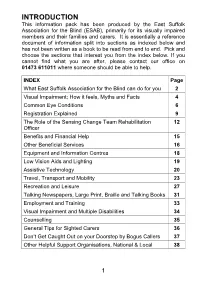

Introduction

INTRODUCTION This information pack has been produced by the East Suffolk Association for the Blind (ESAB), primarily for its visually impaired members and their families and carers. It is essentially a reference document of information split into sections as indexed below and has not been written as a book to be read from end to end. Pick and choose the sections that interest you from the index below. If you cannot find what you are after, please contact our office on 01473 611011 where someone should be able to help. INDEX Page What East Suffolk Association for the Blind can do for you 2 Visual Impairment; How it feels, Myths and Facts 4 Common Eye Conditions 6 Registration Explained 9 The Role of the Sensing Change Team Rehabilitation 12 Officer Benefits and Financial Help 15 Other Beneficial Services 16 Equipment and Information Centres 18 Low Vision Aids and Lighting 19 Assistive Technology 20 Travel, Transport and Mobility 23 Recreation and Leisure 27 Talking Newspapers, Large Print, Braille and Talking Books 31 Employment and Training 33 Visual Impairment and Multiple Disabilities 34 Counselling 35 General Tips for Sighted Carers 36 Don’t Get Caught Out on your Doorstep by Bogus Callers 37 Other Helpful Support Organisations, National & Local 38 1 WHAT CAN EAST SUFFOLK ASSOCIATION FOR THE BLIND DO FOR YOU? If you suffer with any form of eye condition, whether you have reached the stage of being formally registered as sight impaired or severely sight impaired (blind), we would encourage you to contact the East Suffolk Association for the Blind where you are invited to take advantage of the services offered. -

Newspapers: Two Magic Systems with Lots of Sales in Each 3

Multiply your book’s sales by turning your book into 6 Here’s how that works. Let’s say that you have written a book that is 240 body-copy pages long, excluding the front matter, table of contents, bio, and index. Let’s also say that before you wrote the book you created an outline. That outline included an intro/explanation chapter, four systems chapters (each including a different concept and example), and a roll-out chapter that took the four concepts and told how they would work with other information dissemination means, either individually or by working together. That sounds kind of vague, doesn’t it? Here’s an example that might be easier to envision. (I plan my books first, then write.) Its title is How to Sell 75+ of Your Freelance Writing Almost All of the Time. While the book’s contents aren’t related to this blog, its Table of Contents below shows where the six ebooks might come from. It also shows how all of the book(s)—a major paperback of 240+ pages and six ebooks, each from a chapter or section of that paperback—should multiply your total earning power with only about 50-75% more time spent in the ebooks’ preparation, rather than 600% that six books might suggest. Here’s a tentative Table of Contents of my coming book: How to Sell 75+ of Your Freelance Writing Almost All of the Time Introduction 1. Why just sell your writing (idea) once? Why not sell it again and again, then once more—and once again…? 2. -

Coker – Secrets to Ebook Publishing Success

The Secrets to Ebook Publishing Success How to Reach More Readers with Your Words Copyright 2012 Mark Coker Published by Mark Coker at Smashwords Also by Mark Coker, available at ebook retailers everywhere: Smashwords Style Guide (how to format and publish an ebook) Smashwords Book Marketing Guide (how to market any book for free) The 10-Minute PR Checklist (PR strategy for entrepreneurs) Boob Tube (a novel about soap operas) Rev. 5.12.12 Table of Contents Preface Introduction The Secrets Secret 1: Write a great book Secret 2: Pinch your pennies Secret 3: Create a great ebook cover Secret 4: Practice metadata magic Secret 5: Write another great book Secret 6: Build reader trust Secret 7: Embrace your obscurity Secret 8: Spend your time wisely Secret 9: Maximize distribution Secret 10: Avoid exclusivity Secret 11: Give (some of) your books away for FREE Secret 12: Understand the algorithm Secret 13: How retailers select titles for feature promotion Secret 14: Patience pays Secret 15: How books develop (the four behaviors) Secret 16: Trust your customers and supply chain partners Secret 17: Platform building starts yesterday Secret 18: Architect for virality Secret 19: Tweak your viral catalysts Secret 20: Optimize discovery touch points Secret 21: Practice the never-ending book launch Secret 22: Think globally Secret 23: Study the bestsellers Secret 24: Develop a thick skin Secret 25: Think beyond price Secret 26: Ebook publishing is easy, writing is difficult Secret 27: Define your own success Secret 28: Share your secrets Conclusion Free E-Publishing Resources by Mark Coker Other titles by Mark Coker About the Author Appendix I – Glossary of E-Publishing Terms Appendix II – Special acknowledgements for beta readers Appendix III – Credits Appendix IV – Reproduction rights (how to distribute this book freely) Preface The Secrets to Ebook Publishing Success is dedicated to you, the writer. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 Exploring Ereading Devices The fi rst thing to understand about digital publishing is what devices people use to consume digital content, including what types of publications each device class can support, how people use the devices, and where ereading hardware is headed. You will fi nd a startling array of devices on the market, but ultimately there are only four classes of devices on which digital pub- lications are consumed. In this chapter, you will learn about the following: ◆ Device Classes ◆ Ereaders ◆ Tablets ◆ Computers ◆ Mobile Phones ◆ Hybrid Devices ◆ Future Devices Device Classes There is an ever-increasing variety of devices on which to read electronic publications. And the more devices that are out there, the more frequently those devices are upgraded, competing with one another, forcing each other to innovate and improve, and driving the price of ereader owner- ship lower and lower while making electronic content more and more accessible to consumers. That’s good for consumers and for content producers like you and me; competition in ereader hardware, ereader software, tablets, and other devices does most of the work of opening up mar- kets for us. More of these devices are being devised and released every month. In fact, by the time you’ve fi nished readingCOPYRIGHTED this sentence, there will be another—BestBuy.comMATERIAL just listed the newest, greatest ereading device to kill all prior devices! And now—the newest, greatest to kill that one! Of course, there’s also a downside to the feverish pace of device creation and improvement: Creating content that takes full advantage of, or even just fi ts perfectly on the screen of, the cur- rent or next generation of devices is like trying to shoot a bull’s-eye hanging from the fl ank of a bucking bronco while blindfolded. -

Accessing Electronic Books Through EBSCO

Accessing Electronic Books Through EBSCO The library at Henderson Community College provides access to a collection of full text online books through a database called the eBook Collection. This database is now provided by the EBSCO Company, although it was originally an independent database called NetLibrary. As NetLibrary is now owned by EBSCO, its full text books can be retrieved through the EBSCO Company’s link found on the library’s web page. Additionally, all of the eBook Collection’s books are listed in the library’s online catalog which is called Voyager, and all of the eBook Collection books can be accessed through Voyager. Either method allows users to access the over 33,000 books in this collection from any computer with Internet access. Accessing the eBook Collection Through EBSCO On-Campus Access: All of EBSCO’s databases are available to users through any computer that has an HCC IP address. Once logged into a computer, go to the library’s web page, http://www.henderson.kctcs.edu/en/Academics/Library.aspx. Under the heading “Quick Links,” click on the “EBSCO” link. Off-Campus Access: On the library's main web page, click on the "Click Here" link located within the sentence, "If you are off-campus, Click Here, to access the databases." eBooks through EBSCO Tutorial - Page 1 of 10 You will be prompted to enter your username and password. Use the same password you use to log in to the campus computers and your campus email account. Click on "EBSCO" in the Database Menu to access the EBSCO database. -

The Global Ebook Report Germany

Contents About the Global eBook Report Germany. 33 France. 35 Executive Summary. 4 The political and cultural context for ebooks in France. 38 The ambitions, and the limitations of this study. 6 Spain. 39 Global mapping initiatives. 7 Italy. 41 Acknowledgments. 9 Sweden. 42 About the authors of this report. 10 Denmark. 44 Norway. 45 A Global Industry, and Many Local Players Netherlands. 45 Austria. 47 Book publishing as a global industry. 14 Poland. 48 Patterns of change: Digital growth, decline in print, and shifting forces.. 15 Central and Eastern Europe. 49 The accelerating impact of English reading. 50 A comparison of developments across Europe and the US.. 18 The emerging role of ebooks in Central and Eastern Europe. 51 English Language eBook Markets. 23 Slovenia. 51 United States. 23 Lithuania. 52 United Kingdom. 26 Bulgaria. 53 Contributed article Klopotek. How Soon Is Now?. 30 Czech Republic. 53 Start marketing digital content in a future-proof Hungary. 53 way. 30 Romania. 54 Manage products that do not even yet exist. 30 Serbia. 54 Modern planning and production–in its true sense. 30 Contributed article Bookwire. 56 Metadata is the key to online sales success. 31 Availability and discoverability in a global eBook market.. 56 Emerging models for libraries. 31 Get in touch with us. 31 Emerging Markets. 58 We look forward to talking to you.. 31 Russia. 58 Brazil. 61 Europe. 33 The good problem of Brazilian taxes. 64 The Global eBook Report ii China. 67 Methodological issues with regard to the research on piracy. 116 India. 72 Controversial debates, legal initiatives, and The Arab eBook Market.