The Singing of Birds Robyn Howard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biogeography and Biotic Assembly of Indo-Pacific Corvoid Passerine Birds

ES48CH11-Jonsson ARI 9 October 2017 7:38 Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics Biogeography and Biotic Assembly of Indo-Pacific Corvoid Passerine Birds Knud Andreas Jønsson,1 Michael Krabbe Borregaard,1 Daniel Wisbech Carstensen,1 Louis A. Hansen,1 Jonathan D. Kennedy,1 Antonin Machac,1 Petter Zahl Marki,1,2 Jon Fjeldsa˚,1 and Carsten Rahbek1,3 1Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark; email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, 0318 Oslo, Norway 3Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, Ascot SL5 7PY, United Kingdom Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017. 48:231–53 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on Corvides, diversity assembly, evolution, island biogeography, Wallacea August 11, 2017 The Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Abstract Systematics is online at ecolsys.annualreviews.org The archipelagos that form the transition between Asia and Australia were https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316- immortalized by Alfred Russel Wallace’s observations on the connections 022813 between geography and animal distributions, which he summarized in Copyright c 2017 by Annual Reviews. what became the first major modern biogeographic synthesis. Wallace All rights reserved traveled the island region for eight years, during which he noted the marked Access provided by Copenhagen University on 11/19/17. For personal use only. faunal discontinuity across what has later become known as Wallace’s Line. Wallace was intrigued by the bewildering diversity and distribution of Annu. -

The Birds of Pooh Corner Bushland Reserve Species Recorded 2005

The Birds of Pooh Megapodes Ibis & Spoonbills Cockatoos & Corellas (cont'd). Australian Brush-turkey Australian White Ibis Yellow-tailed Black- Corner Bushland Pheasants & Quail Straw-necked Ibis Cockatoo Reserve Brown Quail Eagles, Kites, Goshawks & Parrots, Lorikeets & Rosellas Species recorded Ducks, Geese & Swans Osprey Rainbow Lorikeet Australian Wood Duck Black-shouldered Kite Scaly-breasted Lorikeet 2005 - Nov. 2014 Pacific Black Duck Pacific Baza Little Lorikeet Pigeons & Doves Collared Sparrowhawk Australian King-Parrot Summary: Brown Cuckoo-Dove Whistling Kite Pale-headed Rosella 127 species total - Common Bronzewing Black Kite Cuckoos (a) 118 species recorded by Crested Pigeon Brown Goshawk Australian Koel formal survey 2012-14 Peaceful Dove Grey Goshawk Pheasant Coucal (b) 6 species recorded since Bar-shouldered Dove Wedge-tailed Eagle Channel-billed Cuckoo survey began but not on Rock Dove White-bellied Sea-eagle(Px1) Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo formal survey Frogmouths Falcons Shining Bronze-Cuckoo (c) 3 species recorded prior to Tawny Frogmouth Australian Hobby Little Bronze-Cuckoo and not yet since Birdlife Owlet-Nightjars Crakes, Rails & Swamphens Fan-tailed Cuckoo Southern Queensland survey Australian Owlet-nightjar Purple Swamphen Brush Cuckoo began in Sept. 2012. Swifts & Swiftlets Dusky Moorhen Hawk-Owls White-throated Needletail Plovers, Dotterels & Lapwings Powerful Owl (WACC pre- Legend: Cormorants & Shags Masked Lapwing survey) Px1= private once only record -ie Little Black Cormorant Snipe, Sandpipers et al Masked -

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Australia Part 2 2019 Oct 22, 2019 to Nov 11, 2019 John Coons & Doug Gochfeld For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Water is a precious resource in the Australian deserts, so watering holes like this one near Georgetown are incredible places for concentrating wildlife. Two of our most bird diverse excursions were on our mornings in this region. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Australia. A voyage to the land of Oz is guaranteed to be filled with novelty and wonder, regardless of whether we’ve been to the country previously. This was true for our group this year, with everyone coming away awed and excited by any number of a litany of great experiences, whether they had already been in the country for three weeks or were beginning their Aussie journey in Darwin. Given the far-flung locales we visit, this itinerary often provides the full spectrum of weather, and this year that was true to the extreme. The drought which had gripped much of Australia for months on end was still in full effect upon our arrival at Darwin in the steamy Top End, and Georgetown was equally hot, though about as dry as Darwin was humid. The warmth persisted along the Queensland coast in Cairns, while weather on the Atherton Tablelands and at Lamington National Park was mild and quite pleasant, a prelude to the pendulum swinging the other way. During our final hours below O’Reilly’s, a system came through bringing with it strong winds (and a brush fire warning that unfortunately turned out all too prescient). -

Grand Australia Part Ii: Queensland, Victoria & Plains-Wanderer

GRAND AUSTRALIA PART II: QUEENSLAND, VICTORIA & PLAINS-WANDERER OCTOBER 15–NOVEMBER 1, 2018 Southern Cassowary LEADER: DION HOBCROFT LIST COMPILED BY: DION HOBCROFT VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM GRAND AUSTRALIA PART II By Dion Hobcroft Few birds are as brilliant (in an opposite complementary fashion) as a male Australian King-parrot. On Part II of our Grand Australia tour, we were joined by six new participants. We had a magnificent start finding a handsome male Koala in near record time, and he posed well for us. With friend Duncan in the “monster bus” named “Vince,” we birded through the Kerry Valley and the country towns of Beaudesert and Canungra. Visiting several sites, we soon racked up a bird list of some 90 species with highlights including two Black-necked Storks, a Swamp Harrier, a Comb-crested Jacana male attending recently fledged chicks, a single Latham’s Snipe, colorful Scaly-breasted Lorikeets and Pale-headed Rosellas, a pair of obliging Speckled Warblers, beautiful Scarlet Myzomela and much more. It had been raining heavily at O’Reilly’s for nearly a fortnight, and our arrival was exquisitely timed for a break in the gloom as blue sky started to dominate. Pretty-faced Wallaby was a good marsupial, and at lunch we were joined by a spectacular male Eastern Water Dragon. Before breakfast we wandered along the trail system adjacent to the lodge and were joined by many new birds providing unbelievable close views and photographic chances. Wonga Pigeon and Bassian Thrush were two immediate good sightings followed closely by Albert’s Lyrebird, female Paradise Riflebird, Green Catbird, Regent Bowerbird, Australian Logrunner, three species of scrubwren, and a male Rose Robin amongst others. -

Hollis Taylor: Violinist/Composer/Zoömusicologist

Hollis Taylor: violinist/composer/zoömusicologist Hollis Taylor conducting fieldwork: Newhaven Station, Central Australia, which adjoins Aboriginal freehold land on all sides. (Photo: Jon Rose) Major research: the pied butcherbird (Cracticus nigrogularis). (see “Zoömusicologists” page for audio link Pied butcherbird.mp3) A pied butcherbird, Burleigh Heads, Queensland. (Photo: Hollis Taylor) Other research interests: lyrebirds, bowerbirds, Australian magpies, grey butcherbirds, currawongs, & animal aesthetics. Left: The interior decorations of a western bowerbird’s avenue bower (Alice Springs). His color preferences are green, white, and shiny objects. Right: The exterior decorations of a great bowerbird’s avenue bower (Darwin) display his similar color preferences. (Photos: Hollis Taylor) Satin bowerbirds prefer things blue, with a secondary preference to the color yellow (Blue Mountains, New South Wales). (Photo: Hollis Taylor) Hollis writes: Bowerbird males are vocalists, dancers, architects, interior decorators, collectors, landscape architects, and painters. And bowerbird females are art critics, contemplating what the other sex has created. Selected Publications Taylor, Hollis. 2011. The Australian Pied Butcherbird: The Composer's Muse. Music Forum: Journal of the Music Council of Australia 17 (2). Taylor, Hollis. 2011. Composers’ appropriation of pied butcherbird song: Henry Tate’s ‘undersong of Australia’ comes of age. Journal of Music Research Online. Taylor, Hollis. 2010. Blowin' in Birdland: Improvisation and the Australian pied butcherbird. Leonardo Music Journal 20: 79-83. Taylor, Hollis. 2009. Super Tweeter. Art Monthly Australia 225: 16-19. Taylor, Hollis. 2009. Olivier Messiaen's transcription of the Albert's lyrebird. AudioWings 12 (1): 2-5. Taylor, Hollis. 2009. Location, location, location: Auditioning the vocalizations of the Australian pied butcherbird. Soundscape: The Journal of Acoustic Ecology 9 (1): 14-16. -

Contributions to the Reproductive Effort in a Group of Plural-Breeding Pied Butcherbirds Cracticus Nigrogularis

Australian Field Ornithology 2012, 29, 169–181 Contributions to the reproductive effort in a group of plural-breeding Pied Butcherbirds Cracticus nigrogularis D.G. Gosper 39 Azure Avenue, Balnarring VIC 3926, Australia Email: [email protected] Summary. Concurrent nesting by two females from a single social group of Pied Butcherbirds Cracticus nigrogularis is described. Young fledged from two nests in the first 2 years, but breeding failed in the following two seasons after Australian Magpies C. tibicen displaced the group from its original nest-tree. The two breeding females in the Pied Butcherbird group constructed their nests and incubated synchronously in the same tree without conflict. Only the females constructed the nest and incubated the eggs. Other group members fed the females before laying and during incubation. Females begged for food using a display resembling that of juvenile Butcherbirds. Most (and probably all) members of the group fed the nestlings and fledglings, with multiple members delivering food to the young in both nests and removing or eating faecal sacs. Immatures at the beginning of their second year, with no previous experience, performed the full range of helping tasks, including the provisioning of females from the pre-laying stage. During the nestling stage, the group fed on nectar from Silky Oaks Grevillea robusta, but did not feed this to the young. Introduction The Pied Butcherbird Cracticus nigrogularis (Artamidae) may breed co-operatively (Rowley 1976; Dow 1980; Clarke 1995). Higgins et al. (2006) considered it to be an occasional co-operative breeder, although the only detailed study to date (i.e. -

Brookfield CP Bird List

Bird list for BROOKFIELD CONSERVATION PARK -34.34837 °N 139.50173 °E 34°20’54” S 139°30’06” E 54 362200 6198200 or new birdssa.asn.au ……………. …………….. …………… …………….. … …......... ……… Observers: ………………………………………………………………….. Phone: (H) ……………………………… (M) ………………………………… ..………………………………………………………………………………. Email: …………..…………………………………………………… Date: ……..…………………………. Start Time: ……………………… End Time: ……………………… Codes (leave blank for Present) D = Dead H = Heard O = Overhead B = Breeding B1 = Mating B2 = Nest Building B3 = Nest with eggs B4 = Nest with chicks B5 = Dependent fledglings B6 = Bird on nest NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. NON-PASSERINES S S A W Code No. Rainbow Bee-eater Mulga Parrot Eastern Bluebonnet Red-rumped Parrot Australian Boobook *Feral Pigeon Common Bronzewing Crested Pigeon Australian Bustard Spur-winged Plover Little Buttonquail (Masked Lapwing) Painted Buttonquail Stubble Quail Cockatiel Mallee Ringneck Sulphur-crested Cockatoo (Australian Ringneck) Little Corella Yellow Rosella Black-eared Cuckoo (Crimson Rosella) Fan-tailed Cuckoo Collared Sparrowhawk Horsfield's Bronze Cuckoo Grey Teal Pallid Cuckoo Shining Bronze Cuckoo Peaceful Dove Maned Duck Pacific Black Duck Little Eagle Wedge-tailed Eagle Emu Brown Falcon Peregrine Falcon Tawny Frogmouth Galah Brown Goshawk Australasian Grebe Spotted Harrier White-faced Heron Australian Hobby Nankeen Kestrel Red-backed Kingfisher Black Kite Black-shouldered Kite Whistling Kite Laughing Kookaburra Banded Lapwing Musk Lorikeet Purple-crowned Lorikeet Malleefowl Spotted Nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Australian Owlet-nightjar Blue-winged Parrot Elegant Parrot If Species in BOLD are seen a “Rare Bird Record Report” should be submitted. SEASONS – Spring: September, October, November; Summer: December, January, February; Autumn: March, April May; Winter: June, July, August IT IS IMPORTANT THAT ONLY BIRDS SEEN WITHIN THE RESERVE ARE RECORDED ON THIS LIST. -

Australia&Rsquo

ARTICLE Received 12 Feb 2014 | Accepted 29 Apr 2014 | Published 30 May 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4994 Australia’s arid-adapted butcherbirds experienced range expansions during Pleistocene glacial maxima Anna M. Kearns1,2,3, Leo Joseph4, Alicia Toon1 & Lyn G. Cook1 A model of range expansions during glacial maxima (GM) for cold-adapted species is generally accepted for the Northern Hemisphere. Given that GM in Australia largely resulted in the expansion of arid zones, rather than glaciation, it could be expected that arid-adapted species might have had expanded ranges at GM, as cold-adapted species did in the Northern Hemisphere. For Australian biota, however, it remains paradigmatic that arid-adapted species contracted to refugia at GM. Here we use multilocus data and ecological niche models (ENMs) to test alternative GM models for butcherbirds. ENMs, mtDNA and estimates of nuclear introgression and past population sizes support a model of GM expansion in the arid-tolerant Grey Butcherbird that resulted in secondary contact with its close relative—the savanna-inhabiting Silver-backed Butcherbird—whose contemporary distribution is widely separated. Together, these data reject the universal use of a GM contraction model for Australia’s dry woodland and arid biota. 1 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia. 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, Maryland 21250, USA. 3 Natural History Museum, University of Oslo, PO Box 1172, Blindern, Oslo NO-0318, Norway. 4 Australian National Wildlife Collection, CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, GPO Box 1700, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to A.M.K. -

OF the TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS the Beautiful Lake Ross Stores Over 200,000 Megalitres of Water and Supplies up to 80% of Townsville’S Drinking Water

BIRDS OF THE TOWNSVILLE REGION LAKE ROSS The beautiful Lake Ross stores over 200,000 megalitres of water and supplies up to 80% of Townsville’s drinking water. The Ross River Dam wall stretches 8.3km across the Ross River floodplain, providing additional flood mitigation benefit to downstream communities. The Dam’s extensive shallow margins and fringing woodlands provide habitat for over 200 species of birds. At times, the number of Australian Pelicans, Black Swans, Eurasian Coots and Hardhead ducks can run into the thousands – a magic sight to behold. The Dam is also the breeding area for the White-bellied Sea-Eagle and the Osprey. The park around the Dam and the base of the spillway are ideal habitat for bush birds. The borrow pits across the road from the dam also support a wide variety of water birds for some months after each wet season. Lake Ross and the borrow pits are located at the end of Riverway Drive, about 14km past Thuringowa Central. Birds likely to be seen include: Australasian Darter, Little Pied Cormorant, Australian Pelican, White-faced Heron, Little Egret, Eastern Great Egret, Intermediate Egret, Australian White Ibis, Royal Spoonbill, Black Kite, White-bellied Sea-Eagle, Australian Bustard, Rainbow Lorikeet, Pale-headed Rosella, Blue-winged Kookaburra, Rainbow Bee-eater, Helmeted Friarbird, Yellow Honeyeater, Brown Honeyeater, Spangled Drongo, White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike, Pied Butcherbird, Great Bowerbird, Nutmeg Mannikin, Olive-backed Sunbird. White-faced Heron ROSS RIVER The Ross River winds its way through Townsville from Ross Dam to the mouth of the river near the Townsville Port. -

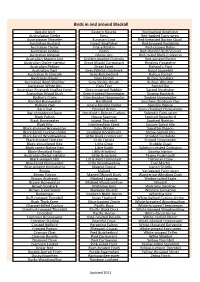

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Final Report Melaleuca Wetlands, Coochiemudlo Island, Fauna Survey 2016 Ronda J Green, Bsc (Hons) Phd

Final Report Melaleuca Wetlands, Coochiemudlo Island, Fauna Survey 2016 Ronda J Green, BSc (Hons) PhD for Coochiemudlo Island Coastcare Supported by Redland City Council Acknowledgements I would like to express thanks to Redland City Council for financial and other support and to Coochiemudlo Island Coastcare for opportunity to conduct the survey, accommodation for Darren and myself, and many kinds of support throughout the process, including the sharing of photos and reports of sightings by others. Volunteers provided invaluable assistance in carrying traps and tools, setting and checking traps, digging holes for pitfall traps and setting associated drift nets, looking for animals on morning and nocturnal searches, collecting and washing traps after the surveys and assisting in other ways. Volunteers were (in alphabetical order): Elissa Brooker, Nikki Cornwall, Raymonde de Lathouder, Lindsay Duncan, Ashley Edwards, Kurt Gaskill, Diane Gilham, Deb Hancox, Margrit Lack, Chris Leonard, Susan Meek, Leigh Purdie, Natascha Quadt, Narelle Renn, Lu Richards, Graeme Roberts-Thomson, Vivienne Roberts-Thomson, Charlie Tomsin, and Bruce Wollstein Thanks also to Carolyn Brammer and Lindsay Duncan for allowing volunteers the use their cabin accommodation for at-cost rates each of the four seasons. Thanks again to Coastcare for providing a number of BBQ's, other meals, tea, coffee and muffins for ourselves and volunteers. Thanks also to Alexandra Beresford and Tim Herse for setting up additional motion-sensing camera, and to Scenic Rim Wildlife for allowing us to borrow theirs. Finally we would like to thank Steve Willson and Patrick Couper of the Queensland Museum for assistance with identification of a snake and a frog.