Reports, P60-231, August 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter R. Orszag

PETER R. ORSZAG Peter R. Orszag is Vice Chairman of Corporate and Investment Banking and Chairman of the Financial Strategy and Solutions Group at Citigroup, Inc. He is also a Nonresident Senior Fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution and a Contributing Columnist at Bloomberg View. Prior to joining Citigroup in January 2011, Dr. Orszag served as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a Contributing Columnist at the New York Times. He previously served as the Director of the Office of Management and Budget in the Obama Administration, a Cabinet-level position, from January 2009 until July 2010. From January 2007 to December 2008, Dr. Orszag was the Director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Under his leadership, the agency significantly expanded its focus on areas such as health care and climate change. Prior to CBO, Dr. Orszag was the Joseph A. Pechman Senior Fellow and Deputy Director of Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution. While at Brookings, he also served as Director of The Hamilton Project, Director of the Retirement Security Project, and Co-Director of the Tax Policy Center. During the Clinton Administration, he was a Special Assistant to the President for Economic Policy and before that a staff economist and then Senior Advisor and Senior Economist at the President's Council of Economic Advisers. Orszag has also founded and subsequently sold an economics consulting firm. Dr. Orszag graduated summa cum laude in economics from Princeton University and obtained a Ph.D. in economics from the London School of Economics, which he attended as a Marshall Scholar. -

ORGANIZING the PRESIDENCY Discussions by Presidential Advisers Back to FDR

A Brookings Book Event STEPHEN HESS BOOK UPDATED: ORGANIZING THE PRESIDENCY Discussions by Presidential Advisers back to FDR The Brookings Institution November 14, 2002 Moderator: STEPHEN HESS Senior Fellow, Governance Studies, Brookings; Eisenhower and Nixon Administrations Panelists: HARRY C. McPHERSON Partner - Piper, Rudnick LLP; Johnson Administration JAMES B. STEINBERG V.P. and Director, Foreign Policy Studies, Brookings; Clinton Administration GENE SPERLING Senior Fellow, Economic Policy, and Director, Center on Universal Education, Council on Foreign Relations; Clinton Administration GEORGE ELSEY President Emeritus, American Red Cross; Roosevelt, Truman Administrations RON NESSEN V.P. of Communications, Brookings; Ford Administration FRED FIELDING Partner, Wiley Rein & Fielding; Nixon, Reagan Administrations Professional Word Processing & Transcribing (801) 942-7044 MR. STEPHEN HESS: Welcome to Brookings. Today we are celebrating the publication of a new edition of my book “Organizing the Presidency,” which was first published in 1976. When there is still interest in a book that goes back more than a quarter of a century it’s cause for celebration. So when you celebrate you invite a bunch of your friends in to celebrate with you. We're here with seven people who have collectively served on the White House staffs of eight Presidents. I can assure you that we all have stories to tell and this is going to be for an hour and a half a chance to tell some of our favorite stories. I hope we'll be serious at times, but I know we're going to have some fun. I'm going to introduce them quickly in order of the President they served or are most identified with, and that would be on my right, George Elsey who is the President Emeritus of the American Red Cross and served on the White House staff of Franklin D. -

The Consequences of Global Educational Expansion

The Consequences of Global Educational Expansion Social Science Perspectives Emily Hannum and Claudia Buchmann project on universal project on universal basic and secondary education basic and secondary education Officers of the American Academy PRESIDENT Patricia Meyer Spacks EXECUTIVE OFFICER Leslie Cohen Berlowitz VICE PRESIDENT Louis W. Cabot SECRETARY Emilio Bizzi TREASURER Peter S. Lynch EDITOR Steven Marcus VICE PRESIDENT, MIDWEST CENTER Martin Dworkin VICE PRESIDENT, WESTERN CENTER John R. Hogness Occasional Papers of the American Academy “Evaluation and the Academy: Are We Doing the Right Thing?” Henry Rosovsky and Matthew Hartley “Trends in American & German Higher Education” Edited by Robert McC. Adams “Making the Humanities Count: The Importance of Data” Robert M. Solow, Francis Oakley, John D’Arms, Phyllis Franklin, Calvin C. Jones “Probing Human Origins” Edited by Morris Goodman and Anne Simon Moffat “War with Iraq: Costs, Consequences, and Alternatives” Carl Kaysen, Steven E. Miller, Martin B. Malin, William D. Nordhaus, John D. Steinbruner To order any of these Occasional Papers please contact the Academy’s Publications Office. Telephone: (617) 576-5085; Fax: (617) 576-5088; E-mail: [email protected] The Consequences of Global Educational Expansion Social Science Perspectives Emily Hannum and Claudia Buchmann © 2003 by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. All rights reserved. ISBN#: 0-87724-039-6 The views expressed in this volume are those held by each contributor and are not necessarily those of the Officers -

2017-2018 Annual Report 2017-2018 View

Founded in 1940, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is the nation’s first civil and human rights law organization and has been completely separate from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1957. From that era to the present, LDF’s mission has always been transformative: to achieve racial justice, equality, and an inclusive society. Photo: LDF Founder Thurgood Marshall contents 02 Message from the Chairs of the Board, Gerald S. Adolph and David W. Mills 04 Message from Sherrilyn Ifill, President and Director-Counsel 07 Litigation 10 A. Education 14 B. Political Participation 18 C. Criminal Justice 22 D. Economic Justice 26 E. Equal Justice 28 F. Supreme Court Advocacy 30 Policy and Advocacy 34 Thurgood Marshall Institute (TMI) 40 LDF in the Media 44 Fellowship and Scholarship Programs 48 Special Events 51 Supporters 61 Financial Report 64 Board of Directors We are proud to say that despite these Gerald S. Adolph mounting threats, LDF remains equal to the task. This annual report is a testament to LDF’s remarkable success in and out of the courtroom. David W. Mills 1 message from the chairs of the board In 1978, LDF’s founder Thurgood Marshall said, “Where you see wrong or inequality or injustice, speak out, because this is your country. This is your democracy. Make it. Protect it. Pass it on.” The NAACP Legal Defense Fund has been pursuing that mission since its founding. Through litigation and advocacy, LDF works to protect and preserve our democracy, so that its promises of liberty and justice can at last be made real for all Americans. -

Orszag to Depart OMB Director Post | 1

Orszag to Depart OMB Director Post | 1 Orszag to Depart OMB Director Post By Editor Test Wed, Jun 30, 2010 “Basically, the OMB Director is a brutal job and subject to quick burnout," commented one political blogger. Peter R. Orszag, who brought a strong retirement perspective to his job as budget director in the Obama administration, will leave the White House later this summer, several news organizations reported last week. “Basically, the OMB Director is a brutal job and subject to quick burnout. I wouldn’t read any more into this than that,” wrote David Dayen on the newsblog, firedoglake, by way of explanation. Orszag’s impending departure was first rumored last April. According to the Washington Post, likely candidates for appointment to the post of director of the Office of Management and Budget include (in order of probability): Laura D. Tyson, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers in the Clinton administration who currently teaches at Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. John Berry, head of the Office of Personnel Management. Rob Nabors, who served as Orszag’s deputy before joining White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel’s office to focus on special projects. Gene Sperling, a senior adviser to Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and a top economic official in the Clinton administration. Robert Greenstein, director of the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities. He served on the Bipartisan Commission on Entitlement and Tax Reform during the Clinton administration. Byron Dorgan, North Dakota’s retiring Democratic senator. Jeffrey Liebman, an economist with expertise on poverty, pensions and Social Security. -

The Case for a Manufacturing Renaissance Prepared Remarks by Gene Sperling the Brookings Institution July 25, 2013

The Case for a Manufacturing Renaissance Prepared Remarks by Gene Sperling The Brookings Institution July 25, 2013 I. Introduction There is little question that President Obama and his economic team have made the revival of manufacturing a key plank of our middle class jobs, innovation, and competitiveness agenda. There is also little question that since the beginning of 2010, U.S. manufacturing has been one of the economy’s bright spots, growing roughly twice as fast as the overall economy. America’s manufacturers have begun to grow production and add jobs in a significant way for the first time in two decades, with over 500,000 jobs added since the beginning of 2010. While no one disputes these basic facts, questions have been raised on three fronts: (i) Is a focus on manufacturing an appropriate public policy priority? (ii) Is manufacturing a promising arena to think about job creation in light of technology, globalization, and productivity trends? (iii) Are we really seeing the promise of a manufacturing renaissance in the United States or just a cyclical recovery? In making the case for the Obama manufacturing strategy, I want to suggest three paradigm shifts that I believe provide a more insightful set of lenses through which to view the impact of manufacturing and the role of policy: (i) First, we need to shift from thinking about the promise of advanced manufacturing from an “industrial policy” model, which is generally framed as picking winners and losers, to an “innovation spillover” model, where we are focused on the degree to which manufacturing location in the United States leads to positive economic and innovation spill-over benefits both for the specific communities impacted as well as for the broader economy. -

Maintaining Stability in a Changing Financial System

The Participants TOBIAS ADRIAN JEANNINE AvERSA Senior Economist Economics Writer Federal Reserve Bank of New York Associated Press SHAMSHAD AKHTAR MARTIN H. BARNES Governor Managing Editor, State Bank of Pakistan The Bank Credit Analyst BCA Research LEWIS ALEXANDER Chief Economist CHARLES BEAN Citi Deputy Governor Bank of England HAMAD AL-SAYARI Governor STEVEN BECKNER Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency Senior Correspondent Market News International SINAN ALSHABIBI Governor C. FRED BERGSTEN Central Bank of Iraq Director Peterson Institute for DAVID E. ALTIG International Economics Senior Vice President and Director of Research RICHARD BERNER Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Co-Head, Global Economics Morgan Stanley, Inc. SHUHEI AOKI General Manager for the Americas BRIAN BLACKSTONE Bank of Japan Special Writer Dow Jones Newswires 679 08 Book.indb 679 2/13/09 3:59:24 PM 680 The Participants ALAN BOLLARD JOSÉ R. DE GREGORIO Governor Governor Reserve Bank of New Zealand Central Bank of Chile HENDRIK BROUWER SErvAAS DEROOSE Executive Director Director De Nederlandsche Bank European Commission JAMES B. BULLARD WILLIAM C. DUDLEY President and Chief Executive Vice President Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of New York Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ROBERT H. DUGGER MARIA TEODORA CARDOSO Managing Director Member of the Board of Directors Tudor Investment Corporation Bank of Portugal ELIZABETH A. DUKE MARK CARNEY Governor Governor Board of Governors of the Bank of Canada Federal Reserve System JOHN CASSIDY CHARLES L. EvANS Staff Writer President and Chief The New Yorker Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago LUC COENE Deputy Governor MARK FELSENTHAL National Bank of Belgium Correspondent Reuters LU CÓRDOVA Chief Executive Officer MIGUEL FERNÁNDEZ Corlund Industries OrDÓÑEZ Governor ANDREW CROCKETT Bank of Spain President JPMorgan Chase International CAMDEN R. -

Biden Cabinet Candidates and Senior White House Positions 4835-4287-3297 V.4.Xlsx

Nominated/Appointed Favored Department Name Description Rep. Cheri Bustos Congresswoman from Illinois; former member of East Moline, Ill. City Council Rep. Marcia Fudge Congresswoman from Ohio; former mayor of Warrensville Heights, Ohio Krysta Harden Former Deputy Agriculture Secretary Senior Fellow in International and Public Affairs at Brown University’s Watson Institute; former senator from North Dakota; former North Dakota attorney Heidi Heitkamp general Amy Klobuchar Minnesota senator; former prosecutor in Minneapolis and candidate for the Democratic nomination AGRICULTURE Kathleen Merrigan Former deputy Agriculture Secretary Collin Peterson Representative from Minnesota and House Agriculture Committee Chairman Chellie Pingree Representative from Maine Karen Ross Former Chief of Staff to Obama Secretary of Agriculture Michael Scuse Delaware Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack Former Iowa governor who served as agriculture secretary for Mr. Obama Xavier Becerra California attorney general; former California congressman and state Assembly member Preet Bharara Former US Attorney for the Southern District of NY Merrick Garland Federal appeals court judge Jeh Johnson Former Obama Homeland Security Secretary ATTORNEY GENERAL/ Doug Jones Alabama senator; former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama JUSTICE Lisa Monaco Former chief counterterrorism and homeland security advisor to Obama Deval Patrick Former Massachusetts Governor Tom Perez Chair of the Democratic National Committee; former secretary of Labor; former assistant attorney general for civil rights Sally Yates Partner, King and Spalding; former acting attorney general and deputy attorney general; former U.S. attorney in the Northern District of Georgia CIA David Cohen Former Deputy CIA Director CLIMATE ENVOY John Kerry Former Secretary of State Jared Bernstein Biden Economic Advisor Heather Boushey Economist Rep. -

Pdfroster of Attendees

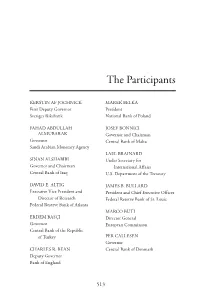

The Participants KERSTIN AF JOCHNICK MAREK BELKA First Deputy Governor President Sveriges Riksbank National Bank of Poland FAHAD ABDULLAH JOSEF BONNICI ALMUBARAK Governor and Chairman Governor Central Bank of Malta Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency LAEL BRAINARD SINAN ALSHABIBI Under Secretary for Governor and Chairman International Affairs Central Bank of Iraq U.S. Department of the Treasury DAVID E. ALTIG JAMES B. BULLARD Executive Vice President and President and Chief Executive Officer Director of Research Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta MARCO BUTI ERDEM BASÇI Director General Governor European Commission Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey PER CALLESEN Governor CHARLES R. BEAN Central Bank of Denmark Deputy Governor Bank of England 513 514 The Participants AGUSTÍN CARSTENS DOUGLAS W. ELMENDORF Governor Director Bank of Mexico Congressional Budget Office NORMAN CHAN WILLIAM B. ENGLISH Chief Executive Director of Monetary Affairs Hong Kong Monetary Authority Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System LUC COENE Governor CHARLES L. EVANS National Bank of Belgium President and Chief Executive Officer Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago JULIA LYNN CORONADO Chief Economist for North America MARTIN FELDSTEIN BNP Paribas President Emeritus, National Bureau of Economic Research CARLOS DA SILVA COSTA Professor, Harvard University Governor Bank of Portugal JACOB A. FRENKEL Chairman CHARLES H. DALLARA JP Morgan Chase International Managing Director Institute of International Finance ARDIAN FULLANI Governor TROY DAVIG Bank of Albania Senior Vice President and Director of Research JOHN GEANAKOPLOS Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Professor Yale University PAUL DEBRUCE CEO and Founder, ESTHER L. GEORGE DeBruce Grain Inc. -

Warm Hearts and Cool Heads: Promoting Growth and Opportunity in a Globalizing Economy

Warm Hearts and Cool Heads: Promoting Growth and Opportunity in a Globalizing Economy Peter R. Orszag1 Joseph A. Pechman Senior Fellow Director, The Hamilton Project The Brookings Institution Remarks at the APEC Symposium on Socio-Economic Disparity June 29, 2006 Thank you. I am quite honored to be returning to APEC about a decade after I participated in the 1997 meetings in the Philippines. And thank you to the government of South Korea for sponsoring this important symposium. The great British economist Alfred Marshall once spoke of the need for “cool heads but warm hearts” in making economic policy.2 The thrust of my speech today is that, in the context of substantial increases in income inequality and given the political economy of globalization, warm hearts are necessary for cool heads – there is no “but” needed.3 Long-term prosperity is best achieved neither through an attempt to shut out the forces of global competition, which may seem warm hearted but is ultimately neither achievable nor desirable, nor through the mirage of an excessively individualistic laissez- faire approach, which may initially seem cool headed but ultimately is not. Instead, policy-makers must embrace the rigors of competition but seek to make economic growth broad-based, to enhance individual economic security, and to design a role for effective government working in conjunction with private markets. These are the themes of the recently launched Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, which actively involves former policy-makers such as former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and former Deputy Treasury Secretary Roger Altman.4 1 The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the staff, officers, or board of the Brookings Institution. -

Trade P LINKY.Indd

THE Advancing Opportunity, HAMILTON Prosperity and Growth PROJECT STRATEGY PAPER J U LY 2 0 0 6 Peter Orszag Michael Deich Growth, Opportunity, and Prosperity in a Globalizing Economy The Brookings Institution The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise of opportunity, prosperity, and growth. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by making economic growth broad-based, by enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role for effective government in making needed public investments. Our strategy—strikingly different from the theories driving current economic policy—calls for fiscal discipline and for increased public investment in key growth- enhancing areas. The Project will put forward innovative policy ideas from leading economic thinkers throughout the United States—ideas based on experience and evidence, not ideology and doctrine—to introduce new, sometimes controversial, policy options into the national debate with the goal of improving our country’s economic policy. The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s first treasury secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern American economy. Consistent with the guiding principles of the Project, Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy, believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary to enhance and guide market forces. THE Advancing Opportunity, HAMILTON Prosperity and Growth PROJECT THE HAMILTON PROJECT Growth, Opportunity, and Prosperity in a Globalizing Economy Peter Orszag Michael Deich The Brookings Institution J U LY 2 0 0 6 GROWTH, OPPORTUNITY, AND PROSPERITY IN A GLOBALIZING ECONOMY The views expressed in this strategy paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of The Hamilton Project Advisory Council or the trustees, officers, or staff members of the Brookings Institution. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Annual Report 2016 The Urban Institute, 2100 M Street NW, Washington, DC 20037 The Brookings Institution, 1775 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20036 http://www.taxpolicycenter.org Letter from the Directors Tax policy was an important topic in public policy discussions A highlight of 2016 was the inaugural Donald C. Lubick in 2016, largely driven by the presidential election. Candidates Symposium, held in May, which featured an address by in the primaries and the general election offered competing Robert Stack, Deputy Assistant Secretary for International visions of how taxes should be structured and the appropriate Taxation at the US Department of the Treasury, as well as level of taxation. Throughout the turbulent process, the Tax a panel of distinguished scholars and practitioners. The Policy Center (TPC) provided timely, accessible, and objective symposium focused on how the tax policies of our major analysis for the public, the media, and policymakers. We foreign trading partners affect US businesses. This annual modeled each major candidate’s tax proposals, estimated event is a fitting tribute to our friend, mentor, and colleague their likely economic effects, and updated the analyses as the in tax policy, Don Lubick. proposals evolved. We then disseminated this work through events, commentary, and publications. During 2016, TPC made several advances to our basic toolkit, which generates many contributions to the tax We hosted three major election-related events in 2016. policy debate. We improved our models in three ways. First, A February gathering featured speeches by both House we updated and improved our microsimulation model. Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady and Second, we implemented “dynamic analyses,” which show Senate Finance Committee Ranking Minority Member how tax proposals affect the overall size of the economy and Ron Wyden.