Chapter 6 Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) – History

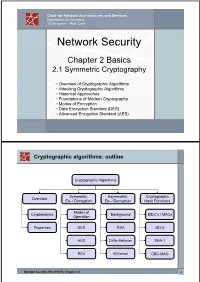

Chair for Network Architectures and Services Department of Informatics TU München – Prof. Carle Network Security Chapter 2 Basics 2.1 Symmetric Cryptography • Overview of Cryptographic Algorithms • Attacking Cryptographic Algorithms • Historical Approaches • Foundations of Modern Cryptography • Modes of Encryption • Data Encryption Standard (DES) • Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Cryptographic algorithms: outline Cryptographic Algorithms Symmetric Asymmetric Cryptographic Overview En- / Decryption En- / Decryption Hash Functions Modes of Cryptanalysis Background MDC’s / MACs Operation Properties DES RSA MD-5 AES Diffie-Hellman SHA-1 RC4 ElGamal CBC-MAC Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 2 Basic Terms: Plaintext and Ciphertext Plaintext P The original readable content of a message (or data). P_netsec = „This is network security“ Ciphertext C The encrypted version of the plaintext. C_netsec = „Ff iThtIiDjlyHLPRFxvowf“ encrypt key k1 C P key k2 decrypt In case of symmetric cryptography, k1 = k2. Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 3 Basic Terms: Block cipher and Stream cipher Block cipher A cipher that encrypts / decrypts inputs of length n to outputs of length n given the corresponding key k. • n is block length Most modern symmetric ciphers are block ciphers, e.g. AES, DES, Twofish, … Stream cipher A symmetric cipher that generats a random bitstream, called key stream, from the symmetric key k. Ciphertext = key stream XOR plaintext Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 4 Cryptographic algorithms: overview -

Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Lecture 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard Lecture Notes on “Computer and Network Security” by Avi Kak ([email protected]) January 26, 2021 3:43pm ©2021 Avinash Kak, Purdue University Goals: To introduce the notion of a block cipher in the modern context. To talk about the infeasibility of ideal block ciphers To introduce the notion of the Feistel Cipher Structure To go over DES, the Data Encryption Standard To illustrate important DES steps with Python and Perl code CONTENTS Section Title Page 3.1 Ideal Block Cipher 3 3.1.1 Size of the Encryption Key for the Ideal Block Cipher 6 3.2 The Feistel Structure for Block Ciphers 7 3.2.1 Mathematical Description of Each Round in the 10 Feistel Structure 3.2.2 Decryption in Ciphers Based on the Feistel Structure 12 3.3 DES: The Data Encryption Standard 16 3.3.1 One Round of Processing in DES 18 3.3.2 The S-Box for the Substitution Step in Each Round 22 3.3.3 The Substitution Tables 26 3.3.4 The P-Box Permutation in the Feistel Function 33 3.3.5 The DES Key Schedule: Generating the Round Keys 35 3.3.6 Initial Permutation of the Encryption Key 38 3.3.7 Contraction-Permutation that Generates the 48-Bit 42 Round Key from the 56-Bit Key 3.4 What Makes DES a Strong Cipher (to the 46 Extent It is a Strong Cipher) 3.5 Homework Problems 48 2 Computer and Network Security by Avi Kak Lecture 3 Back to TOC 3.1 IDEAL BLOCK CIPHER In a modern block cipher (but still using a classical encryption method), we replace a block of N bits from the plaintext with a block of N bits from the ciphertext. -

Development of the Advanced Encryption Standard

Volume 126, Article No. 126024 (2021) https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.126.024 Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Development of the Advanced Encryption Standard Miles E. Smid Formerly: Computer Security Division, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD 20899, USA [email protected] Strong cryptographic algorithms are essential for the protection of stored and transmitted data throughout the world. This publication discusses the development of Federal Information Processing Standards Publication (FIPS) 197, which specifies a cryptographic algorithm known as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). The AES was the result of a cooperative multiyear effort involving the U.S. government, industry, and the academic community. Several difficult problems that had to be resolved during the standard’s development are discussed, and the eventual solutions are presented. The author writes from his viewpoint as former leader of the Security Technology Group and later as acting director of the Computer Security Division at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, where he was responsible for the AES development. Key words: Advanced Encryption Standard (AES); consensus process; cryptography; Data Encryption Standard (DES); security requirements, SKIPJACK. Accepted: June 18, 2021 Published: August 16, 2021; Current Version: August 23, 2021 This article was sponsored by James Foti, Computer Security Division, Information Technology Laboratory, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). The views expressed represent those of the author and not necessarily those of NIST. https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.126.024 1. Introduction In the late 1990s, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) was about to decide if it was going to specify a new cryptographic algorithm standard for the protection of U.S. -

Chapter 3 – Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Symmetric Cryptography Chapter 6 Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted – Like a substitution on very big characters • 64-bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting – Many current ciphers are block ciphers • Better analyzed. • Broader range of applications. Block vs Stream Ciphers Block Cipher Principles • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64-bit block • Arbitrary reversible substitution cipher for a large block size is not practical – 64-bit general substitution block cipher, key size 264! • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Needed since must be able to decrypt ciphertext to recover messages efficiently Ideal Block Cipher Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • in 1949 Shannon introduced idea of substitution- permutation (S-P) networks – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations we have seen before: – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) (transposition) • Provide confusion and diffusion of message Diffusion and Confusion • Introduced by Claude Shannon to thwart cryptanalysis based on statistical analysis – Assume the attacker has some knowledge of the statistical characteristics of the plaintext • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this Diffusion -

The Long Road to the Advanced Encryption Standard

The Long Road to the Advanced Encryption Standard Jean-Luc Cooke CertainKey Inc. [email protected], http://www.certainkey.com/˜jlcooke Abstract 1 Introduction This paper will start with a brief background of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) process, lessons learned from the Data Encryp- tion Standard (DES), other U.S. government Two decades ago the state-of-the-art in cryptographic publications and the fifteen first the private sector cryptography was—we round candidate algorithms. The focus of the know now—far behind the public sector. presentation will lie in presenting the general Don Coppersmith’s knowledge of the Data design of the five final candidate algorithms, Encryption Standard’s (DES) resilience to and the specifics of the AES and how it dif- the then unknown Differential Cryptanaly- fers from the Rijndael design. A presentation sis (DC), the design principles used in the on the AES modes of operation and Secure Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) in Digital Hash Algorithm (SHA) family of algorithms Signature Standard (DSS) being case and will follow and will include discussion about point[NISTDSS][NISTDES][DC][NISTSHA1]. how it is directly implicated by AES develop- ments. The selection and design of the DES was shrouded in controversy and suspicion. This very controversy has lead to a fantastic acceler- Intended Audience ation in private sector cryptographic advance- ment. So intrigued by the NSA’s modifica- tions to the Lucifer algorithm, researchers— This paper was written as a supplement to a academic and industry alike—powerful tools presentation at the Ottawa International Linux in assessing block cipher strength were devel- Symposium. -

A Proposed SAFER Plus Security Algorithm Using Fast Walsh Hadamard Transform for Bluetooth Technology D.Sharmila 1, R.Neelaveni 2

International Journal of Wireless & Mobile Networks (IJWMN), Vol 1, No 2, November 2009 A Proposed SAFER Plus Security algorithm using Fast Walsh Hadamard transform for Bluetooth Technology D.Sharmila 1, R.Neelaveni 2 1(Research Scholar), Associate Professor, Bannari Amman Institute of Technology, Sathyamangalam. Tamil Nadu-638401. [email protected] 2 Asst.Prof. PSG College of Technology, Coimbatore.Tamil Nadu -638401. [email protected] ABSTRACT realtime two-way voice transfer providing data rates up to 3 Mb/s. It operates at 2.4 GHz frequency in the free ISM-band (Industrial, Scientific, and Medical) using frequency hopping In this paper, a modified SAFER plus algorithm is [18]. Bluetooth can be used to connect almost any kind of presented. Additionally, a comparison with various device to another device. Typical range of Bluetooth communication varies from 10 to 100 meters indoors. security algorithms like pipelined AES, Triple DES, Bluetooth technology and associated devices are susceptible Elliptic curve Diffie Hellman and the existing SAFER plus to general wireless networking threats, such as denial of service attacks, eavesdropping, man-in-the-middle attacks, are done. Performance of the algorithms is evaluated message modification, and resource misappropriation. They based on the data throughput, frequency and security are also threatened by more specific Bluetooth-related attacks that target known vulnerabilities in Bluetooth level. The results show that the modified SAFER plus implementations and specifications. Attacks against algorithm has enhanced security compared to the existing improperly secured Bluetooth implementations can provide attackers with unauthorized access to sensitive information algorithms. and unauthorized usage of Bluetooth devices and other Key words : Secure And Fast Encryption Routine, Triple Data systems or networks to which the devices are connected. -

Chapter 2 the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

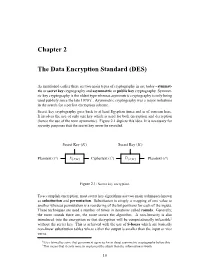

Chapter 2 The Data Encryption Standard (DES) As mentioned earlier there are two main types of cryptography in use today - symmet- ric or secret key cryptography and asymmetric or public key cryptography. Symmet- ric key cryptography is the oldest type whereas asymmetric cryptography is only being used publicly since the late 1970’s1. Asymmetric cryptography was a major milestone in the search for a perfect encryption scheme. Secret key cryptography goes back to at least Egyptian times and is of concern here. It involves the use of only one key which is used for both encryption and decryption (hence the use of the term symmetric). Figure 2.1 depicts this idea. It is necessary for security purposes that the secret key never be revealed. Secret Key (K) Secret Key (K) ? ? - - - - Plaintext (P ) E{P,K} Ciphertext (C) D{C,K} Plaintext (P ) Figure 2.1: Secret key encryption. To accomplish encryption, most secret key algorithms use two main techniques known as substitution and permutation. Substitution is simply a mapping of one value to another whereas permutation is a reordering of the bit positions for each of the inputs. These techniques are used a number of times in iterations called rounds. Generally, the more rounds there are, the more secure the algorithm. A non-linearity is also introduced into the encryption so that decryption will be computationally infeasible2 without the secret key. This is achieved with the use of S-boxes which are basically non-linear substitution tables where either the output is smaller than the input or vice versa. 1It is claimed by some that government agencies knew about asymmetric cryptography before this. -

The Aes Project Any Lessons For

THE AES PROJECT: Any Lessons for NC3? THOMAS A. BERSON, ANAGRAM LABORATORIES Technology for Global Security | June 23, 2020 THE AES PROJECT: ANY LESSONS FOR NC3? THOMAS A. BERSON JUNE 23, 2020 I. INTRODUCTION In this report, Tom Berson details how lessons from the Advanced Encryption Standard Competition can aid the development of international NC3 components and even be mirrored in the creation of a CATALINK1 community. Tom Berson is a cryptologist and founder of Anagram Laboratories. Contact: [email protected] This paper was prepared for the Antidotes for Emerging NC3 Technical Vulnerabilities, A Scenarios-Based Workshop held October 21-22, 2019 and convened by The Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, Technology for Global Security, The Stanley Center for Peace and Security, and hosted by The Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) Stanford University. A podcast with Tom Berson and Philip Reiner can be found here. It is published simultaneously here by Technology for Global Security and here by Nautilus Institute and is published under a 4.0 International Creative Commons License the terms of which are found here. Acknowledgments: The workshop was funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Maureen Jerrett provided copy editing services. Banner image is by Lauren Hostetter of Heyhoss Design II. TECH4GS SPECIAL REPORT BY TOM BERSON THE AES PROJECT: ANY LESSONS FOR NC3? JUNE 23, 2020 1. THE AES PROJECT From 1997 through 2001, the National Institute for Standards and Technology (US) (NIST) ran an open, transparent, international competition to design and select a standard block cipher called the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)2. -

Cryptography Overview Cryptography Basic Cryptographic Concepts Five

CS 155 Spring 2006 Cryptography Is A tremendous tool Cryptography Overview The basis for many security mechanisms Is not John Mitchell The solution to all security problems Reliable unless implemented properly Reliable unless used properly Something you should try to invent yourself unless you spend a lot of time becoming an expert you subject your design to outside review Basic Cryptographic Concepts Five-Minute University Encryption scheme: functions to encrypt, decrypt data key generation algorithm Secret key vs. public key -1 Public key: publishing key does not reveal key -1 Father Guido Sarducci Secret key: more efficient, generally key = key Hash function, MAC Everything you could remember, five Map input to short hash; ideally, no collisions MAC (keyed hash) used for message integrity years after taking CS255 … ? Signature scheme Functions to sign data, verify signature Web Purchase Secure communication 1 Secure Sockets Layer / TLS SSL/TLS Cryptography Standard for Internet security Public-key encryption Key chosen secretly (handshake protocol) Originally designed by Netscape Key material sent encrypted with public key Goal: “... provide privacy and reliability between two communicating applications” Symmetric encryption Two main parts Shared (secret) key encryption of data packets Signature-based authentication Handshake Protocol Client can check signed server certificate Establish shared secret key using public-key cryptography Signed certificates for authentication And vice-versa, in principal Record -

A Comparison of Cryptographic Algorithms: DES, 3DES, AES, RSA

www.symbiosisonline.org www.symbiosisonlinepublishing.com Symbiosis ISSN Online: 2474-9257 Research Article Journal of Computer Science Applications and Information Technology Open Access A Comparison of Cryptographic Algorithms: DES, 3DES, AES, RSA and Blowfish for Guessing Attacks Prevention Mohammed Nazeh Abdul Wahid*, Abdulrahman Ali, Babak Esparham and Mohamed Marwan Limkokwing University of Creative and Technology, Post Graduate Centre, Cyberjaya, Malaysia Received: June 22, 2018; Accepted: July 12, 2018; Published: August 10, 2018 *Corresponding author: Mohammed Nazeh Abdul Wahid, Senior Lecturer, Limkokwing university of creative technology, Post Graduate Centre, Cyberjaya, Malaysia, Tel: +60104339985; E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Encryption is the process of encoding information or data in key (also called secret-key) and Asymmetric-key (called public- order to prevent unauthorized access. These days we need to secure key) encryption [2]. the information that is stored in our computer or is transmitted via evaluation is a network security system for an application using internet against attacks. There are different types of cryptographic the Aproposed secure Wi-Fi algorithm. system As for for wireless some cryptographicnetworks: experimental system, it methods that can be used. Basically, the selecting cryptographic is commonly used to secure communication channels by using method depends on the application demands such as the response public key exchanges based on algorithms such as RSA, DES, AES, cryptographic algorithms has its own weak and strong points. In this paper,time, bandwidth,we will present confidentiality the result of and the implementationintegrity. However, and analysiseach of the key used to encrypt data sent over an unsecured Internet that applied on several cryptographic algorithms such as DES, 3DES, channel.Triple DES In andaddition, Blowfish. -

Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES)

Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) 2021.03.09 Presented by: Mikail Mohammed Salim Professor 박종혁 Cryptography and Information Security 1 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) Contents • What is Block Cipher? • Padding in Block Cipher • Ideal Block Cipher • What is DES? • DES- Key Discarding Process • Des- 16 rounds of Encryption • How secure is DES? 2 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) What is Block Cipher? • An encryption technique that applies an algorithm with parameters to encrypt blocks of text. • Each plaintext block has an equal length of ciphertext block. • Each output block is the same size as the input block, the block being transformed by the key. • Block size range from 64 -128 bits and process the plaintext in blocks of 64 or 128 bits. • Several bits of information is encrypted with each block. Longer messages are encoded by invoking the cipher repeatedly. 3 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) What is Block Cipher? • Each message (p) grouped in blocks is encrypted (enc) using a key (k) into a Ciphertext (c). Therefore, 푐 = 푒푛푐푘(푝) • The recipient requires the same k to decrypt (dec) the p. Therefore, 푝 = 푑푒푐푘(푐) 4 Block Cipher and Data Encryption Standard (DES) Padding in Block Cipher • Block ciphers process blocks of fixed sizes, such as 64 or 128 bits. The length of plaintexts is mostly not a multiple of the block size. • A 150-bit plaintext provides two blocks of 64 bits each with third block of remaining 22 bits. • The last block of bits needs to be padded up with redundant information so that the length of the final block equal to block size of the scheme. -

Miss in the Middle Attacks on IDEA and Khufu

Miss in the Middle Attacks on IDEA and Khufu Eli Biham? Alex Biryukov?? Adi Shamir??? Abstract. In a recent paper we developed a new cryptanalytic techni- que based on impossible differentials, and used it to attack the Skipjack encryption algorithm reduced from 32 to 31 rounds. In this paper we describe the application of this technique to the block ciphers IDEA and Khufu. In both cases the new attacks cover more rounds than the best currently known attacks. This demonstrates the power of the new cryptanalytic technique, shows that it is applicable to a larger class of cryptosystems, and develops new technical tools for applying it in new situations. 1 Introduction In [5,17] a new cryptanalytic technique based on impossible differentials was proposed, and its application to Skipjack [28] and DEAL [17] was described. In this paper we apply this technique to the IDEA and Khufu cryptosystems. Our new attacks are much more efficient and cover more rounds than the best previously known attacks on these ciphers. The main idea behind these new attacks is a bit counter-intuitive. Unlike tra- ditional differential and linear cryptanalysis which predict and detect statistical events of highest possible probability, our new approach is to search for events that never happen. Such impossible events are then used to distinguish the ci- pher from a random permutation, or to perform key elimination (a candidate key is obviously wrong if it leads to an impossible event). The fact that impossible events can be useful in cryptanalysis is an old idea (for example, some of the attacks on Enigma were based on the observation that letters can not be encrypted to themselves).