Differential Cryptanalysis of the Data Encryption Standard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improved Cryptanalysis of the Reduced Grøstl Compression Function, ECHO Permutation and AES Block Cipher

Improved Cryptanalysis of the Reduced Grøstl Compression Function, ECHO Permutation and AES Block Cipher Florian Mendel1, Thomas Peyrin2, Christian Rechberger1, and Martin Schl¨affer1 1 IAIK, Graz University of Technology, Austria 2 Ingenico, France [email protected],[email protected] Abstract. In this paper, we propose two new ways to mount attacks on the SHA-3 candidates Grøstl, and ECHO, and apply these attacks also to the AES. Our results improve upon and extend the rebound attack. Using the new techniques, we are able to extend the number of rounds in which available degrees of freedom can be used. As a result, we present the first attack on 7 rounds for the Grøstl-256 output transformation3 and improve the semi-free-start collision attack on 6 rounds. Further, we present an improved known-key distinguisher for 7 rounds of the AES block cipher and the internal permutation used in ECHO. Keywords: hash function, block cipher, cryptanalysis, semi-free-start collision, known-key distinguisher 1 Introduction Recently, a new wave of hash function proposals appeared, following a call for submissions to the SHA-3 contest organized by NIST [26]. In order to analyze these proposals, the toolbox which is at the cryptanalysts' disposal needs to be extended. Meet-in-the-middle and differential attacks are commonly used. A recent extension of differential cryptanalysis to hash functions is the rebound attack [22] originally applied to reduced (7.5 rounds) Whirlpool (standardized since 2000 by ISO/IEC 10118-3:2004) and a reduced version (6 rounds) of the SHA-3 candidate Grøstl-256 [14], which both have 10 rounds in total. -

Key-Dependent Approximations in Cryptanalysis. an Application of Multiple Z4 and Non-Linear Approximations

KEY-DEPENDENT APPROXIMATIONS IN CRYPTANALYSIS. AN APPLICATION OF MULTIPLE Z4 AND NON-LINEAR APPROXIMATIONS. FX Standaert, G Rouvroy, G Piret, JJ Quisquater, JD Legat Universite Catholique de Louvain, UCL Crypto Group, Place du Levant, 3, 1348 Louvain-la-Neuve, standaert,rouvroy,piret,quisquater,[email protected] Linear cryptanalysis is a powerful cryptanalytic technique that makes use of a linear approximation over some rounds of a cipher, combined with one (or two) round(s) of key guess. This key guess is usually performed by a partial decryp- tion over every possible key. In this paper, we investigate a particular class of non-linear boolean functions that allows to mount key-dependent approximations of s-boxes. Replacing the classical key guess by these key-dependent approxima- tions allows to quickly distinguish a set of keys including the correct one. By combining different relations, we can make up a system of equations whose solu- tion is the correct key. The resulting attack allows larger flexibility and improves the success rate in some contexts. We apply it to the block cipher Q. In parallel, we propose a chosen-plaintext attack against Q that reduces the required number of plaintext-ciphertext pairs from 297 to 287. 1. INTRODUCTION In its basic version, linear cryptanalysis is a known-plaintext attack that uses a linear relation between input-bits, output-bits and key-bits of an encryption algorithm that holds with a certain probability. If enough plaintext-ciphertext pairs are provided, this approximation can be used to assign probabilities to the possible keys and to locate the most probable one. -

25 Years of Linear Cryptanalysis -Early History and Path Search Algorithm

25 Years of Linear Cryptanalysis -Early History and Path Search Algorithm- Asiacrypt 2018, December 3 2018 Mitsuru Matsui © Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Back to 1990… 2 © Mitsubishi Electric Corporation FEAL (Fast data Encipherment ALgorithm) • Designed by Miyaguchi and Shimizu (NTT). • 64-bit block cipher family with the Feistel structure. • 4 rounds (1987) • 8 rounds (1988) • N rounds(1990) N=32 recommended • Key size is 64 bits (later extended to 128 bits). • Optimized for 8-bit microprocessors (no lookup tables). • First commercially successful cipher in Japan. • Inspired many new ideas, including linear cryptanalysis. 3 © Mitsubishi Electric Corporation FEAL-NX Algorithm [Miyaguchi 90] subkey 4 © Mitsubishi Electric Corporation The Round Function of FEAL 2-byte subkey Linear Relations 푌 2 = 푋1 0 ⊕ 푋2 0 푌 2 = 푋1 0 ⊕ 푋2 0 ⊕ 1 (푁표푡푎푡푖표푛: 푌 푖 = 푖-푡ℎ 푏푖푡 표푓 푌) 5 © Mitsubishi Electric Corporation Linear Relations of the Round Function Linear Relations 푂 16,26 ⊕ 퐼 24 = 퐾 24 K 푂 18 ⊕ 퐼 0,8,16,24 = 퐾 8,16 ⊕ 1 푂 10,16 ⊕ 퐼 0,8 = 퐾 8 S 0 푂 2,8 ⊕ 퐼 0 = 퐾 0 ⊕ 1 (푁표푡푎푡푖표푛: 퐴 푖, 푗, 푘 = 퐴 푖 ⊕ 퐴 푗 ⊕ 퐴 푘 ) S1 O I f S0 f 3-round linear relations with p=1 S1 f modified round function f at least 3 subkey (with whitening key) f bytes affect output6 6 © Mitsubishi Electric Corporation History of Cryptanalysis of FEAL • 4-round version – 100-10000 chosen plaintexts [Boer 88] – 20 chosen plaintexts [Murphy 90] – 8 chosen plaintexts [Biham, Shamir 91] differential – 200 known plaintexts [Tardy-Corfdir, Gilbert 91] – 5 known plaintexts [Matsui, Yamagishi -

Basic Cryptography

Basic cryptography • How cryptography works... • Symmetric cryptography... • Public key cryptography... • Online Resources... • Printed Resources... I VP R 1 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz How cryptography works • Plaintext • Ciphertext • Cryptographic algorithm • Key Decryption Key Algorithm Plaintext Ciphertext Encryption I VP R 2 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Simple cryptosystem ... ! ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ ! DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC • Caesar Cipher • Simple substitution cipher • ROT-13 • rotate by half the alphabet • A => N B => O I VP R 3 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys cryptosystems … • keys and keyspace ... • secret-key and public-key ... • key management ... • strength of key systems ... I VP R 4 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Keys and keyspace … • ROT: key is N • Brute force: 25 values of N • IDEA (international data encryption algorithm) in PGP: 2128 numeric keys • 1 billion keys / sec ==> >10,781,000,000,000,000,000,000 years I VP R 5 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Symmetric cryptography • DES • Triple DES, DESX, GDES, RDES • RC2, RC4, RC5 • IDEA Key • Blowfish Plaintext Encryption Ciphertext Decryption Plaintext Sender Recipient I VP R 6 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz DES • Data Encryption Standard • US NIST (‘70s) • 56-bit key • Good then • Not enough now (cracked June 1997) • Discrete blocks of 64 bits • Often w/ CBC (cipherblock chaining) • Each blocks encr. depends on contents of previous => detect missing block I VP R 7 © Copyright 2002-2007 Haim Levkowitz Triple DES, DESX, -

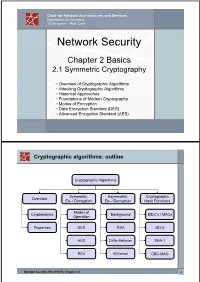

The Data Encryption Standard (DES) – History

Chair for Network Architectures and Services Department of Informatics TU München – Prof. Carle Network Security Chapter 2 Basics 2.1 Symmetric Cryptography • Overview of Cryptographic Algorithms • Attacking Cryptographic Algorithms • Historical Approaches • Foundations of Modern Cryptography • Modes of Encryption • Data Encryption Standard (DES) • Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) Cryptographic algorithms: outline Cryptographic Algorithms Symmetric Asymmetric Cryptographic Overview En- / Decryption En- / Decryption Hash Functions Modes of Cryptanalysis Background MDC’s / MACs Operation Properties DES RSA MD-5 AES Diffie-Hellman SHA-1 RC4 ElGamal CBC-MAC Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 2 Basic Terms: Plaintext and Ciphertext Plaintext P The original readable content of a message (or data). P_netsec = „This is network security“ Ciphertext C The encrypted version of the plaintext. C_netsec = „Ff iThtIiDjlyHLPRFxvowf“ encrypt key k1 C P key k2 decrypt In case of symmetric cryptography, k1 = k2. Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 3 Basic Terms: Block cipher and Stream cipher Block cipher A cipher that encrypts / decrypts inputs of length n to outputs of length n given the corresponding key k. • n is block length Most modern symmetric ciphers are block ciphers, e.g. AES, DES, Twofish, … Stream cipher A symmetric cipher that generats a random bitstream, called key stream, from the symmetric key k. Ciphertext = key stream XOR plaintext Network Security, WS 2010/11, Chapter 2.1 4 Cryptographic algorithms: overview -

Tuto Documentation Release 0.1.0

Tuto Documentation Release 0.1.0 DevOps people 2020-05-09 09H16 CONTENTS 1 Documentation news 3 1.1 Documentation news 2020........................................3 1.1.1 New features of sphinx.ext.autodoc (typing) in sphinx 2.4.0 (2020-02-09)..........3 1.1.2 Hypermodern Python Chapter 5: Documentation (2020-01-29) by https://twitter.com/cjolowicz/..................................3 1.2 Documentation news 2018........................................4 1.2.1 Pratical sphinx (2018-05-12, pycon2018)...........................4 1.2.2 Markdown Descriptions on PyPI (2018-03-16)........................4 1.2.3 Bringing interactive examples to MDN.............................5 1.3 Documentation news 2017........................................5 1.3.1 Autodoc-style extraction into Sphinx for your JS project...................5 1.4 Documentation news 2016........................................5 1.4.1 La documentation linux utilise sphinx.............................5 2 Documentation Advices 7 2.1 You are what you document (Monday, May 5, 2014)..........................8 2.2 Rédaction technique...........................................8 2.2.1 Libérez vos informations de leurs silos.............................8 2.2.2 Intégrer la documentation aux processus de développement..................8 2.3 13 Things People Hate about Your Open Source Docs.........................9 2.4 Beautiful docs.............................................. 10 2.5 Designing Great API Docs (11 Jan 2012)................................ 10 2.6 Docness................................................. -

Cryptanalysis of Substitution-Permutation Networks Using Key-Dependent Degeneracy*

Cryptanalysis of Substitution-Permutation Networks Using Key-Dependent Degeneracy* Howard M. Heys Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada A1B 3X5 Stafford E.Tavares Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada K7L 3N6 * This research was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Telecommunications Research Institute of Ontario and was completed during the first author’s doctoral studies at Queen’s University. Cryptanalysis of Substitution-Permutation Networks Using Key-Dependent Degeneracy Keywords Ð Cryptanalysis, Substitution-Permutation Network, S-box Abstract Ð This paper presents a novel cryptanalysis of Substitution- Permutation Networks using a chosen plaintext approach. The attack is based on the highly probable occurrence of key-dependent degeneracies within the network and is applicable regardless of the method of S-box keying. It is shown that a large number of rounds are required before a network is re- sistant to the attack. Experimental results have found 64-bit networks to be cryptanalyzable for as many as 8 to 12 rounds depending on the S-box properties. ¡ . Introduction The concept of Substitution-Permutation Networks (SPNs) for use in block cryp- tosystem design originates from the “confusion” and “diffusion” principles in- troduced by Shannon [1]. The SPN architecture considered in this paper was first suggested by Feistel [2] and consists of rounds of non-linear substitutions (S-boxes) connected by bit permutations. Such a cryptosystem structure, referred 1 to as LUCIFER1 by Feistel, is a simple, efficient implementation of Shannon’s concepts. -

Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard

Lecture 3: Block Ciphers and the Data Encryption Standard Lecture Notes on “Computer and Network Security” by Avi Kak ([email protected]) January 26, 2021 3:43pm ©2021 Avinash Kak, Purdue University Goals: To introduce the notion of a block cipher in the modern context. To talk about the infeasibility of ideal block ciphers To introduce the notion of the Feistel Cipher Structure To go over DES, the Data Encryption Standard To illustrate important DES steps with Python and Perl code CONTENTS Section Title Page 3.1 Ideal Block Cipher 3 3.1.1 Size of the Encryption Key for the Ideal Block Cipher 6 3.2 The Feistel Structure for Block Ciphers 7 3.2.1 Mathematical Description of Each Round in the 10 Feistel Structure 3.2.2 Decryption in Ciphers Based on the Feistel Structure 12 3.3 DES: The Data Encryption Standard 16 3.3.1 One Round of Processing in DES 18 3.3.2 The S-Box for the Substitution Step in Each Round 22 3.3.3 The Substitution Tables 26 3.3.4 The P-Box Permutation in the Feistel Function 33 3.3.5 The DES Key Schedule: Generating the Round Keys 35 3.3.6 Initial Permutation of the Encryption Key 38 3.3.7 Contraction-Permutation that Generates the 48-Bit 42 Round Key from the 56-Bit Key 3.4 What Makes DES a Strong Cipher (to the 46 Extent It is a Strong Cipher) 3.5 Homework Problems 48 2 Computer and Network Security by Avi Kak Lecture 3 Back to TOC 3.1 IDEAL BLOCK CIPHER In a modern block cipher (but still using a classical encryption method), we replace a block of N bits from the plaintext with a block of N bits from the ciphertext. -

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, Newdes, RC2, and TEA

Related-Key Cryptanalysis of 3-WAY, Biham-DES,CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA John Kelsey Bruce Schneier David Wagner Counterpane Systems U.C. Berkeley kelsey,schneier @counterpane.com [email protected] f g Abstract. We present new related-key attacks on the block ciphers 3- WAY, Biham-DES, CAST, DES-X, NewDES, RC2, and TEA. Differen- tial related-key attacks allow both keys and plaintexts to be chosen with specific differences [KSW96]. Our attacks build on the original work, showing how to adapt the general attack to deal with the difficulties of the individual algorithms. We also give specific design principles to protect against these attacks. 1 Introduction Related-key cryptanalysis assumes that the attacker learns the encryption of certain plaintexts not only under the original (unknown) key K, but also under some derived keys K0 = f(K). In a chosen-related-key attack, the attacker specifies how the key is to be changed; known-related-key attacks are those where the key difference is known, but cannot be chosen by the attacker. We emphasize that the attacker knows or chooses the relationship between keys, not the actual key values. These techniques have been developed in [Knu93b, Bih94, KSW96]. Related-key cryptanalysis is a practical attack on key-exchange protocols that do not guarantee key-integrity|an attacker may be able to flip bits in the key without knowing the key|and key-update protocols that update keys using a known function: e.g., K, K + 1, K + 2, etc. Related-key attacks were also used against rotor machines: operators sometimes set rotors incorrectly. -

Camellia: a 128-Bit Block Cipher Suitable for Multiple Platforms

Copyright NTT and Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 2000 Camellia: A 128-Bit Block Cipher Suitable for Multiple Platforms † ‡ † Kazumaro Aoki Tetsuya Ichikawa Masayuki Kanda ‡ † ‡ ‡ Mitsuru Matsui Shiho Moriai Junko Nakajima Toshio Tokita † Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation 1-1 Hikarinooka, Yokosuka, Kanagawa, 239-0847 Japan {maro,kanda,shiho}@isl.ntt.co.jp ‡ Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5-1-1 Ofuna, Kamakura, Kanagawa, 247-8501 Japan {ichikawa,matsui,june15,tokita}@iss.isl.melco.co.jp September 26, 2000 Abstract. We present a new 128-bit block cipher called Camellia. Camellia sup- ports 128-bit block size and 128-, 192-, and 256-bit key lengths, i.e. the same interface specifications as the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Camellia was carefully designed to withstand all known cryptanalytic attacks and even to have a sufficiently large security leeway for use of the next 10-20 years. There are no hidden weakness inserted by the designers. It was also designed to have suitability for both software and hardware implementations and to cover all possible encryption applications that range from low-cost smart cards to high-speed network systems. Compared to the AES finalists, Camellia offers at least comparable encryption speed in software and hardware. An optimized implementation of Camellia in assembly language can en- crypt on a PentiumIII (800MHz) at the rate of more than 276 Mbits per second, which is much faster than the speed of an optimized DES implementation. In ad- dition, a distinguishing feature is its small hardware design. The hardware design, which includes key schedule, encryption and decryption, occupies approximately 11K gates, which is the smallest among all existing 128-bit block ciphers as far as we know. -

Serpent: a Proposal for the Advanced Encryption Standard

Serpent: A Proposal for the Advanced Encryption Standard Ross Anderson1 Eli Biham2 Lars Knudsen3 1 Cambridge University, England; email [email protected] 2 Technion, Haifa, Israel; email [email protected] 3 University of Bergen, Norway; email [email protected] Abstract. We propose a new block cipher as a candidate for the Ad- vanced Encryption Standard. Its design is highly conservative, yet still allows a very efficient implementation. It uses S-boxes similar to those of DES in a new structure that simultaneously allows a more rapid avalanche, a more efficient bitslice implementation, and an easy anal- ysis that enables us to demonstrate its security against all known types of attack. With a 128-bit block size and a 256-bit key, it is as fast as DES on the market leading Intel Pentium/MMX platforms (and at least as fast on many others); yet we believe it to be more secure than three-key triple-DES. 1 Introduction For many applications, the Data Encryption Standard algorithm is nearing the end of its useful life. Its 56-bit key is too small, as shown by a recent distributed key search exercise [28]. Although triple-DES can solve the key length problem, the DES algorithm was also designed primarily for hardware encryption, yet the great majority of applications that use it today implement it in software, where it is relatively inefficient. For these reasons, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology has issued a call for a successor algorithm, to be called the Advanced Encryption Standard or AES. -

Miss in the Middle

Miss in the middle By: Gal Leonard Keret Miss in the Middle Attacks on IDEA, Khufu and Khafre • Written by: – Prof. Eli Biham. – Prof. Alex Biryukov. – Prof. Adi Shamir. Introduction • So far we used traditional differential which predict and detect statistical events of highest possible probability. Introduction • A new approach is to search for events with probability one, whose condition cannot be met together (events that never happen). Impossible Differential • Random permutation: 휎 푀0 = 푎푛푦 퐶 표푓 푠푖푧푒 푀0. • Cipher (not perfect): 퐸 푀0 = 푠표푚푒 퐶 표푓 푠푖푧푒 푀0. • Events (푚 ↛ 푐) that never happen distinguish a cipher from a random permutation. Impossible Differential • Impossible events (푚 ↛ 푐) can help performing key elimination. • All the keys that lead to impossibility are obviously wrong. • This way we can filter wrong key guesses and leaving the correct key. Enigma – for example • Some of the attacks on Enigma were based on the observation that letters can not be encrypted to themselves. 퐸푛푖푔푚푎(푀0) ≠ 푀0 In General • (푀0, 퐶1) is a pair. If 푀0 푀0 → 퐶1. • 푀 ↛ 퐶 . 0 0 Some rounds For any key • ∀ 푘푒푦| 퐶1 → 퐶0 ↛ is an impossible key. Cannot lead to 퐶0. Some rounds Find each keys Decrypt 퐶1back to 퐶0. IDEA • International Data Encryption Algorithm. • First described in 1991. • Block cipher. • Symmetric. • Key sizes: 128 bits. • Block sizes: 64 bits. ⊕ - XOR. ⊞ - Addition modulo 216 ⊙ - Multiplication modulo 216+1 Encryption security • Combination of different mathematical groups. • Creation of "incompatibility“: ∗ • 푍216+1 → 푍216 ∗ • 푍216 → 푍216+1 ∗ ∗ Remark: 푍216+1 doesn’t contain 0 like 푍216 , so in 푍216+1 0 will be converted to 216 since 0 ≡ 216(푚표푑 216).