The Echtrae As an Early Irish Literaiy Genre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish Narrative Literature with Particular Reference to Tales Belonging to the Ulster Cycle

The role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish narrative literature with particular reference to tales belonging to the Ulster Cycle. Mary Leenane, B.A. 2 Volumes Vol. 1 Ph.D. Degree NUI Maynooth School of Celtic Studies Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies and Philosophy Head of School: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Supervisor: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn June 2014 Table of Contents Volume 1 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I: General Introduction…………………………………………………2 I.1. Ulster Cycle material………………………………………………………...…2 I.2. Modern scholarship…………………………………………………………...11 I.3. Methodologies………………………………………………………………...14 I.4. International heroic biography………………………………………………..17 Chapter II: Sources……………………………………………………………...23 II.1. Category A: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a significant role…………...23 II.2. Category B: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a more limited role………...41 II.3. Category C: Texts in which Cú Chulainn makes a very minor appearance or where reference is made to him…………………………………………………...45 II.4. Category D: The tales in which Cú Chulainn does not feature………………50 Chapter III: Cú Chulainn’s heroic biography…………………………………53 III.1. Cú Chulainn’s conception and birth………………………………………...54 III.1.1. De Vries’ schema………………...……………………………………………………54 III.1.2. Relevant research to date…………………………………………………………...…55 III.1.3. Discussion and analysis…………………………………………………………...…..58 III.2. Cú Chulainn’s youth………………………………………………………...68 III.2.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………68 III.2.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………69 III.2.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..78 III.3. Cú Chulainn’s wins a maiden……………………………………………….90 III.3.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………90 III.3.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………91 III.3.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..95 III.3.4 Further comment……………………………………………………………………...108 III.4. -

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Pilgrimage Stories: the Farmer Fairy's Stone

PILGRIMAGE STORIES: THE FARMER FAIRY’S STONE By Betty Lou Chaika One of the primary intentions of our recent six-week pilgrimage, first to Scotland and then to Ireland, was to visit EarthSpirit sanctuaries in these ensouled landscapes. We hoped to find portals to the Otherworld in order to contact renewing, healing, transformative energies for us all, and especially for some friends with cancer. I wanted to learn how to enter the field of divinity, the aliveness of the EarthSpirit world’s interpenetrating energies, with awareness and respect. Interested in both geology and in our ancestors’ spiritual relationship with Rock, I knew this quest would involve a deeper meeting with rock beings in their many forms. When we arrived at a stone circle in southwest Ireland (whose Gaelic name means Edges of the Field) we were moved by the familiar experience of seeing that the circle overlooks a vast, beautiful landscape. Most stone circles seem to be in places of expansive power, part of a whole sacred landscape. To the north were the lovely Paps of Anu, the pair of breast-shaped hills, both over 2,000 feet high, named after Anu/Aine, the primary local fertility goddess of the region, or after Anu/Danu, ancient mother goddess of the supernatural beings, the Tuatha De Danann. The summits of both hills have Neolithic cairns, which look exactly like erect nipples. This c. 1500 BC stone circle would have drawn upon the power of the still-pervasive earlier mythology of the land as the Mother’s body. But today the tops of the hills were veiled in low, milky clouds, and we could only long for them to be revealed. -

Definitive Version Thesis Kruithof FAYE.Pdf

War is (not) a board-game The function of medieval Irish board games and their players Bachelor’s thesis Kruithof, F.A.Y.E. Word count: 8188 16-10-2018 Supervisor: Petrovskaia, N. Celtic Languages and Culture Utrecht University List of content Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Previous research.................................................................................................................... 5 Theoretical framework ........................................................................................................... 7 Approach and sources ............................................................................................................ 9 Chapter One: Players in the Ulster Cycle: Opponents ............................................................. 11 Eochaid Airem and Midir of Brí Leith ................................................................................. 11 Manannán mac Lir and Fand ................................................................................................ 12 Cú Chulainn and Láeg mac Riangabra ................................................................................. 13 Conchobar, -

Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung As a Junction Within Lebor Gabála Érenn

Edinburgh Research Explorer Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn Citation for published version: Thanisch, E 2013, Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn. in Quaestio Insularis: Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon Norse and Celtic. vol. 13, pp. 69-93. <http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/publications/quaestio/Quaestio2012.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaestio Insularis General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor 1 Gabála Érenn INTRODUCTION Lebor Gabála Érenn: Content Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘the Book of the Invasion of Ireland’) is the conventional title for a lengthy Irish pseudo-historical text extant in multiple recensions probably compiled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 The text comprises a history of the Gaídil (‘Gaels’) within the context of a universal history derived from the Bible and from Classical historiography.3 Lebor Gabála traces the ancestry of the Gaídil back to Noah and follows their tortuous migrations, spanning many generations, from the Tower of Babel to Ireland via Spain. -

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

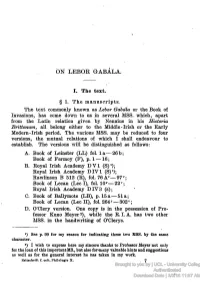

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

The Wooing of Emer and Other Stories

The Ulster Cycle: The Wooing of Emer and other stories by Patrick Brown The fullest version of The Wooing of Emer is found in the Book of Leinster (c.1160) in a text dating from the tenth or eleventh century. An earlier, fragmentary version is found in several manuscripts, including Lebor na hUidre (the Book of the Dun Cow, c.1106). This retelling is based on both versions. Cú Chulainn’s Shield is an anecdote found in the manuscript H.3.17. This is my own translation, with thanks to Breandán Dalton, Dennis King, and especially David Stifter for their help and suggestions. The Death of Aífe’s Only Son is found in the Yellow Book of Lecan, compiled about 1390, but the language of the story dates from the ninth or tenth century. The Death of Derbforgaill is found in the Book of Leinster. The Elopement of Emer comes from the late 14th Century Stowe MS No 992. The Training of Cú Chulainn is a late, alternative version of Cú Chulainn’s travels and training. It is found in no less than eleven different manuscripts, the earliest being Egerton 106, dated to 1715. The Ulster Cycle: The Wooing of Emer and other stories © Patrick Brown 2002/2008 The Wooing of Emer A great and famous king, Conchobor son of Fachtna Fathach, once ruled in Emain Macha, and his reign was one of peace and prosperity and abundance and order. His house, the Red Branch, built in the likeness of the Tech Midchuarta in Tara, was very impressive, with nine compartments from the fire to the wall, separated by thirty-foot-high bronze partitions. -

Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 The aW rped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth Martha J. Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lee, M. J.(2019). The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5278 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Warped One: Nationalist Adaptations of the Cuchulain Myth By Martha J. Lee Bachelor of Business Administration University of Georgia, 1995 Master of Arts Georgia Southern University, 2003 ________________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Ed Madden, Major Professor Scott Gwara, Committee Member Thomas Rice, Committee Member Yvonne Ivory, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Martha J. Lee, 2019 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This dissertation and degree belong as much or more to my family as to me. They sacrificed so much while I traveled and studied; they supported me, loved and believed in me, fed me, and made sure I had the time and energy to complete the work. My cousins Monk and Carolyn Phifer gave me a home as well as love and support, so that I could complete my course work in Columbia. -

Literature and Learning in Early Medieval Meath

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Literature and learning in early medieval Meath Author(s) Downey, Clodagh Publication Date 2015 Downey, Clodagh (2015) 'Literature and Learning in Early Publication Medieval Meath' In: Crampsie, A., and Ludlow, F(Eds.). Information Meath History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County. Dublin : Geography Publications. Publisher Geography Publications Link to publisher's http://www.geographypublications.com/product/meath-history- version society/ Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/7121 Downloaded 2021-09-26T15:35:58Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. CHAPTER 04 - Clodagh Downey 7/20/15 1:11 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 4 Literature and learning in early medieval Meath CLODAGH DOWNEY The medieval literature of Ireland stands out among the vernacular literatures of western Europe for its volume, its diversity and its antiquity, and within this treasury of cultural riches, Meath holds a prominence greatly disproportionate to its geographical extent, however that extent is reckoned. Indeed, the first decision confronting anyone who wishes to consider this subject is to define its geographical limits: the modern county of Meath is quite a different entity to the medieval kingdom of Mide from which it gets its name and which itself designated different areas at different times. It would be quite defensible to include in a survey of medieval literature those areas which are now under the administration of other modern counties, but which may have been part of the medieval kingdom at the time that that literature was produced. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark.