The Collector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mammoth Cave ; How I

OUTHBERTSON WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 Mails. Publications : The Mammoth Cave ; D'ACHE, Caran (Emmanuel Poire), cari- How I found the Gainsborough Picture ; caturist b. in ; Russia ; grandfather French Conciliation in the North of Coal ; England ; grandmother Russian. Drew political Mine to Cabinet ; Interviews from Prince cartoons in the "Figaro; Caran D'Ache is to Peasant, etc. Recreations : cycling, Russian for lead pencil." Address : fchological studies. Address : 33 Walton Passy, Paris. [Died 27 Feb. 1909. 1 ell Oxford. Club : Koad, Oxford, Reform. Sir D'AGUILAR, Charles Lawrence, G.C.B ; [Died 2 Feb. 1903. cr. 1887 ; Gen. b. 14 (retired) ; May 1821 ; CUTHBERTSON, Sir John Neilson ; Kt. cr, s. of late Lt.-Gen. Sir George D'Aguilar, 1887 ; F.E.I.S., D.L. Chemical LL.D., J.P., ; K.C.B. d. and ; m. Emily, of late Vice-Admiral Produce Broker in Glasgow ; ex-chair- the Hon. J. b. of of School Percy, C.B., 5th Duke of man Board of Glasgow ; member of the Northumberland, 1852. Educ. : Woolwich, University Court, Glasgow ; governor Entered R. 1838 Mil. Sec. to the of the Glasgow and West of Scot. Technical Artillery, ; Commander of the Forces in China, 1843-48 ; Coll. ; b. 13 1829 m. Glasgow, Apr. ; Mary served Crimea and Indian Mutiny ; Gen. Alicia, A. of late W. B. Macdonald, of commanding Woolwich district, 1874-79 Rammerscales, 1865 (d. 1869). Educ. : ; Lieut.-Gen. 1877 ; Col. Commandant School and of R.H.A. High University Glasgow ; Address : 4 Clifton Folkestone. Coll. Royal of Versailles. Recreations: Crescent, Clubs : Travellers', United Service. having been all his life a hard worker, had 2 Nov. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

The Chatsworth Fine Art Sale

THE CHATSWORTH FINE ART SALE On the instructions of: • The Executors of the late Mrs. Jane Avril de Montmorency Wright, of Burnchurch House and Castle Morres, Co. Kilkenny; • The Newport Family, descendants of Sir John Newport, formerly of New Park, Co. Waterford, Chancellor of the Irish Exchequer; • Contents of Victoria Lodge, Dublin 4; • Blenheim House, Waterford; • No. 9 Fitzwilliam Square & Tassagart House, Saggart, Co. Dublin; • & Property from other Trustees, Executors and Important Private Clients. AT THE OLD CINEMA, CHATSWORTH STREET, Lot 517 CASTLECOMER, CO. KILKENNy Auction: Wednesday, February 25th, 2015 Commencing at 10.30am sharp Online bidding available Viewing: via the-saleroom.com (surcharge applies) At our Auction Rooms, The Old Cinema Chatsworth Street, Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny Sunday, February 22nd: 12.00 – 17.00 Monday, February 23rd: 10.30 – 17.00 Tuesday, February 24th: 10.30 – 17.00 Follow us on Twitter @FonsieMealy (Note: Children must be accompanied and supervised by an adult) Inside Front Cover Illustration: Illustrated catalogue: €10.00 (l-r) Lots 23, 122, 25,107, 616, 672, 179, 673 Inside Back Cover Illustration: Lot 566 Sale Reference: 0233 Back Cover Illustration: Lot 565 The Old Cinema, Chatsworth St., Castlecomer, Co. Kilkenny, Ireland fm T: +353 56 4441229 | F: +353 56 4441627 | E: [email protected] | W: www.fonsiemealy.ie PSRA Registration No: 001687 Design & Print: Lion Print, Cashel. 062-61258 Mr. Fonsie Mealy F.R.I.C.S. Mr. George Fonsie Mealy B.A. Director Director [email protected] [email protected] PADDLE BIDDING If the purchaser is attending the auction in person they must register for a paddle prior to the auction. -

© 2012 Marlia Fontaine-Weisse All Rights Reserved

© 2012 MARLIA FONTAINE-WEISSE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “LEARNED GEM TACTICS”: EXPLORING VALUE THROUGH GEMSTONES AND OTHER PRECIOUS MATERIALS IN EMILY DICKINSON’S POETRY A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Marlia Fontaine-Weisse December, 2012 “LEARNED GEM TACTICS”: EXPLORING VALUE THROUGH GEMSTONES AND OTHER PRECIOUS MATERIALS IN EMILY DICKINSON’S POETRY Marlia Fontaine-Weisse Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ ________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Jon Miller Chand Midha, Ph.D. _______________________________ ________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Mary Biddinger George R. Newkome, Ph.D. _______________________________ ________________________________ Faculty Reader Date Dr. Patrick Chura _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dr. Hillary Nunn _______________________________ Department Chair Dr. William Thelin ii ABSTRACT Reading Emily Dickinson’s use of pearls, diamonds, and gold and silver alongside periodicals available during her day helps to build a stronger sense of what the popular American cultural conceptions were regarding those materials and the entities they influenced. After looking at pearls in “The Malay – took the Pearl –” (Fr451) in Chapter II, we discover how Dickinson’s invocation of a specific kind of racial other, the Malay, and the story she constructs around them provides a very detailed view of the level of racial bias reserved for the Malay race, especially in relation to their role in the pearl industry. Most criticism regarding her gemstone use centers upon the various layers of interpretation fleshed out from her work rather than also looking to her poems as a source of musings on actual geo-political occurrences. -

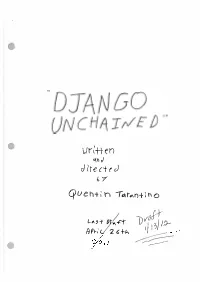

Django Unchained (2012) Screenplay

' \Jl't-H- en �'1 J drtecitJ b/ qu eh+; h -r�r... n+ l ho ,r Lo\5-t- () .<..+-t vof I 3/ I;)-- ftp�;L 2 t 1-h 1) \ I ' =------- I EXT - COUNTRYSIDE - BROILING HOT DAY As the film's OPENING CREDIT SEQUENCE plays, complete with its own SPAGHETTI WESTERN THEME SONG, we see SEVEN shirtless and shoeless BLACK MALE SLAVES connected together with LEG IRONS, being run, by TWO WHITE MALE HILLBILLIES on HORSEBACK. The location is somewhere in Texas. The Black Men (ROY, BIG SID, BENJAMIN, DJANGO, PUDGY RALPH, FRANKLYN, and BLUEBERRY) are slaves just recently purchased at The Greenville Slave Auction in Greenville Mississippi. The White Hillbillies are two Slave Traders called, The SPECK BROTHERS (ACE and DICKY). One of the seven slaves is our hero DJANGO.... he's fourth in the leg iron line. We may or may not notice a tiny small "r" burned into his cheek ("r" for runaway), but we can't help but notice his back which has been SLASHED TO RIBBONS by Bull Whip Beatings. As the operatic Opening Theme Song plays, we see a MONTAGE of misery and pain, as Django and the Other Men are walked through blistering sun, pounding rain, and moved along by the end of a whip. Bare feet step on hard rock, and slosh through mud puddles. Leg Irons take the skin off ankles. DJANGO Walking in Leg Irons with his six Other Companions, walking across the blistering Texas panhandle .... remembering... thinking ... hating .... THE OPENING CREDIT SEQUENCE end. EXT - WOODS - NIGHT It's night time and The Speck Brothers, astride HORSES, keep pushing their black skinned cargo forward. -

Vermont Commons School Summer Reading List 2011

Vermont Commons School Summer Reading List 2011 . 2011Common Texts: 7th and 8th Grades: To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th Grades: A Stranger in the Kingdom by Howard Frank Mosher Dear Parents, Students, and Friends, The Language Arts Department is excited to share this year’s Common Text selections, the Summer Reading Lists, and assignments. Our Common Texts this year are To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, for 7th and 8th grades and A Stranger in the Kingdom by Howard Frank Mosher, for 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades. Vermont Commons wants to join with the Vermont Council on the Humanities to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of Harper Lee’s class novel of innocence, prejudice, and the moral awakening of a young girl. Mosher’s novel is a perfect partner book to Lee’s as it depicts similar themes and targets an older audience. Students will read about diversity in each text and will be involved in activities surrounding this theme throughout the year. Once again, we’ve divided the reading list into three categories: (1) Classics and Prize Winners (2) Books that Speak to the VCS Mission Statement (3) Other Books for Summer. We are asking students to choose a book from two of the categories, as well as the Common Text, for a total of three books to be read this summer. Finally, some students have asked for quick summaries of the books on our list, so we have provided some short descriptions at the end of the lists. For more summaries, we encourage students to browse the bookstore or an online bookseller such as Barnes & Noble.com. -

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index

THE WALTER STANLEY CAMPBELL COLLECTION Inventory and Index Revised and edited by Kristina L. Southwell Associates of the Western History Collections Norman, Oklahoma 2001 Boxes 104 through 121 of this collection are available online at the University of Oklahoma Libraries website. THE COVER Michelle Corona-Allen of the University of Oklahoma Communication Services designed the cover of this book. The three photographs feature images closely associated with Walter Stanley Campbell and his research on Native American history and culture. From left to right, the first photograph shows a ledger drawing by Sioux chief White Bull that depicts him capturing two horses from a camp in 1876. The second image is of Walter Stanley Campbell talking with White Bull in the early 1930s. Campbell’s oral interviews of prominent Indians during 1928-1932 formed the basis of some of his most respected books on Indian history. The third photograph is of another White Bull ledger drawing in which he is shown taking horses from General Terry’s advancing column at the Little Big Horn River, Montana, 1876. Of this act, White Bull stated, “This made my name known, taken from those coming below, soldiers and Crows were camped there.” Available from University of Oklahoma Western History Collections 630 Parrington Oval, Room 452 Norman, Oklahoma 73019 No state-appropriated funds were used to publish this guide. It was published entirely with funds provided by the Associates of the Western History Collections and other private donors. The Associates of the Western History Collections is a support group dedicated to helping the Western History Collections maintain its national and international reputation for research excellence. -

Sartor Resartus: the Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh

Sartor Resartus The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh Thomas Carlyle This public-domain (U.S.) text was scanned and proofed by Ron Burkey. The Project Gutenberg edition (“srtrs10”) was subse- quently converted to LATEX using GutenMark software and re-edited with lyx software. The frontispiece, which was not included in the Project Gutenberg edition, has been restored. Report problems to [email protected]. Revi- sion B1 differs from B0a in that “—-” has ev- erywhere been replaced by “—”. Revision: B1 Date: 01/29/2008 Contents BOOK I. 3 CHAPTER I. PRELIMINARY. 3 CHAPTER II. EDITORIAL DIFFICULTIES. 11 CHAPTER III. REMINISCENCES. 17 CHAPTER IV. CHARACTERISTICS. 33 CHAPTER V. THE WORLD IN CLOTHES. 43 CHAPTER VI. APRONS. 53 CHAPTER VII. MISCELLANEOUS-HISTORICAL. 57 CHAPTER VIII. THE WORLD OUT OF CLOTHES. 63 CHAPTER IX. ADAMITISM. 71 CHAPTER X. PURE REASON. 79 i ii CHAPTER XI. PROSPECTIVE. 87 BOOK II. 101 CHAPTER I. GENESIS. 101 CHAPTER II. IDYLLIC. 113 CHAPTER III. PEDAGOGY. 125 CHAPTER IV. GETTING UNDER WAY. 147 CHAPTER V. ROMANCE. 163 CHAPTER VI. SORROWS OF TEUFELSDRÖCKH. 181 CHAPTER VII. THE EVERLASTING NO. 195 CHAPTER VIII. CENTRE OF INDIFFERENCE. 207 CHAPTER IX. THE EVERLASTING YEA. 223 CHAPTER X. PAUSE. 239 BOOK III. 251 CHAPTER I. INCIDENT IN MODERN HISTORY. 251 CHAPTER II. CHURCH-CLOTHES. 259 iii CHAPTER III. SYMBOLS. 265 CHAPTER IV. HELOTAGE. 275 CHAPTER V. THE PHOENIX. 281 CHAPTER VI. OLD CLOTHES. 289 CHAPTER VII. ORGANIC FILAMENTS. 295 CHAPTER VIII. NATURAL SUPERNATURALISM. 307 CHAPTER IX. CIRCUMSPECTIVE. 323 CHAPTER X. THE DANDIACAL BODY. 329 CHAPTER XI. TAILORS. 349 CHAPTER XII. FAREWELL. 355 APPENDIX. -

Politics, Profit and Reform

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , October . # Cambridge University Press DOI: .\SX Printed in the United Kingdom The Montmorencys and the Abbey of Sainte TriniteT, Caen: Politics, Profit and Reform by JOAN DAVIES Female religious, especially holders of benefices, made significant contributions to aristocratic family strategy and fortune in early modern France. This study of members of the wider Montmorency family in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries demonstrates the financial and political benefits derived from female benefice holding. Abbey stewards and surintendants of aristocratic households collaborated in the administration of religious revenues. Montmorency control of Sainte TriniteT, the Abbaye aux Dames, Caen, for over a century was associated with attempts to assert political influence in Normandy. Conflict ostensibly over religious reform could have a political dimension. Yet reform could be pursued vigorously by those originally cloistered for mercenary or political reasons. ecent studies of early modern nuns have emphasised the importance of family strategy in their experience. Dynasticism Rwithin convents and enforced monachisation of women to preserve family inheritances are two aspects of this strategy evident in early modern Italy, particularly Tuscany; in sixteenth-century France, the importance of female networks centred on abbeys has been noted as a significant dimension of aristocratic patronage. Such phenomena were not incompatible with reform in female religious orders which, in the context of early modern France, embraces both the impact of Protestan- " tism and renewal of Catholic devotion. This survey of nuns from the extended Montmorency family in the sixteenth and early seventeenth AMC, L l Archives du Muse! e Conde! Chantilly, series L; AN l Archives nationales; BN, Fr. -

Fasig-Tipton

Barn E2 Hip No. Consigned by Roger Daly, Agent 1 Perfect Lure Mr. Prospector Forty Niner . { File Twining . Never Bend { Courtly Dee . { Tulle Perfect Lure . Baldski Dark bay/br. mare; Cause for Pause . { *Pause II foaled 1998 {Causeimavalentine . Bicker (1989) { Iza Valentine . { Countess Market By TWINING (1991), [G2] $238,140. Sire of 7 crops, 23 black type win- ners, 248 winners, $17,515,772, including Two Item Limit (7 wins, $1,060,585, Demoiselle S. [G2], etc.), Pie N Burger [G3] (to 6, 2004, $912,133), Connected [G3] ($525,003), Top Hit [G3] (to 6, 2004, $445,- 357), Tugger ($414,920), Dawn of the Condor [G2] ($399,615). 1st dam CAUSEIMAVALENTINE, by Cause for Pause. 2 wins at 3, $28,726. Dam of 4 other foals of racing age, including a 2-year-old of 2004, one to race. 2nd dam Iza Valentine, by Bicker. 5 wins, 2 to 4, $65,900, 2nd Las Madrinas H., etc. Half-sister to AZU WERE. Dam of 11 winners, including-- FRAN’S VALENTINE (f. by Saros-GB). 13 wins, 2 to 5, $1,375,465, Santa Susana S. [G1], Kentucky Oaks [G1], Hollywood Oaks [G1]-ntr, Santa Maria H. [G2], Chula Vista H. [G2], Las Virgenes S. [G3], Princess S. [G3], Yankee Valor H. [L], B. Thoughtful H. (SA, $27,050), Dulcia H. (SA, $27,200), Black Swan S., Bustles and Bows S., 2nd Breeders’ Cup Distaff [G1], Hollywood Starlet S.-G1, Alabama S. [G1], etc. Dam of 5 winners, including-- WITH ANTICIPATION (c. by Relaunch). 15 wins, 2 to 7, placed at 9, 2004, $2,660,543, Sword Dancer Invitational H. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected