Bruce Douglas Crumpton Date of Degree: August 4, 1956 Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

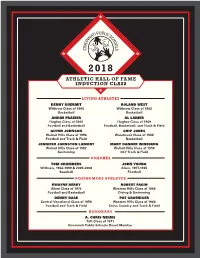

Class of 2018

2018 ATHLETIC Hall OF FaME INDUCTION ClaSS LIVING ATHLETES DENNY DUERMIT ROLAND WEST Withrow Class of 1969 Withrow Class of 1962 Basketball Basketball ANDRE FRAZIER AL LaNIER Hughes Class of 2000 Hughes Class of 1969 Football and Basketball Football, Basketball, and Track & Field GLYNN JOHNSON CHIP JONES Walnut Hills Class of 1996 Woodward Class of 1988 Football and Track & Field Basketball JENNIFER JOHNSTON LaMONT MaRY DANNER WINEBERG Walnut Hills Class of 1982 Walnut Hills Class of 1998 Swimming OLY Track & Field COACHES TOM CHAMBERS JOHN YOUNG Withrow, 1966-1999 & 2005-2008 Aiken, 1977-1985 Baseball Football POSTHUMOUS ATHLETES DwaYNE BERRY ROBERT FagIN Aiken Class of 1975 Western Hills Class of 1946 Football and Basketball Diving & Swimming DENNY DASE PaT GROENIGER Central Vocational Class of 1959 Western Hills Class of 1946 Football and Track & Field Cross Country and Track & Field HONORARY A. CHRIS NELMS Taft Class of 1971 Cincinnati Public Schools Board Member WELCOME TO THE 2018 CPS ATHLETIC HALL OF FAME INDUCTION CEREMONY HOSTED BY PRESENTED BY THURSDAY, APRIL 19, 2018 SOCIal HOUR: 5PM | WELCOME AND DINNER: 6PM INDUCTION CEREMONY: 7PM MASTERS OF CEREMONY John Popovich, Sports Director WCPO Channel 9 Lincoln Ware, SOUL 101.5 COAch INDucTEES Tom Chambers, Withrow High School John Young, Aiken High School POSThumOUS INDucTEES Dwayne Berry, Aiken High School Denny Dase, Central Vocational High School Robert Fagin, Western Hills High School Pat Groeniger, Western Hills High School Livi2018NG AThlETE INDucTEES Denny Duermit, Withrow High School Andre Frazier, Hughes High School Glynn Johnson, Walnut Hills High School Jennifer Johnston LaMont, Walnut Hills High School Roland West, Withrow High School Chip Jones, Woodward High School Al Lanier, Hughes High School Mary Danner Wineberg, Walnut Hills High School HONORARY INDucTEE A. -

Business Brd Mtng 8-26-19

August 26 2019 BOARD OF EDUCATION CINCINNATI, OHIO PROCEEDINGS BUSINESS MEETING August 26, 2019 Table of Contents Roll Call . 963 Minutes Approved . 963 Report of the Finance Committee August 15, 2019 . 963 Report of the Policy Committee August 22, 2019 . 978 Presentations . 981 Announcements/Hearing of the Public . 981 Board Matters . 982 A Resolution to Request a Waiver for Alcohol Use at Withrow High School by the Withrow High School Alumni Association . 982 A Resolution to Request a Waiver for Alcohol Use at the School for the Creative and Performing Arts by the SCPA Fund . 983 Report of the Superintendent Recommendations of the Superintendent of Schools . 1. Certificated Personnel . 985 2. Civil Service Personnel . 994 Report of the Treasurer I. Agreements . 1002 II. Amendment to Agreements. .. 1004 III. Late Requests . 1004 IV. Award of Purchase Orders . 1007 V. Then and Now Certificates . 1008 VI. Payments .. 1010 VII. For Board Information . 1011 VIII. Community Reinvestment Act Agreements . 1015 IX. Corrections . 1017 X. Grant Awards . 1018 Inquiries/Updates . 1023 Assignments . 1023 Adjournment . 1023 August 26 963 2019 REGULAR MEETING The Board of Education of the City School District of the City of Cincinnati, Ohio, met pursuant to its calendar of meetings in the ILC at the Cincinnati Public Schools Education Center, 2651 Burnet Avenue, Monday, August 26, 2019 at 6:32 p.m., President Jones in the chair. The pledge to the flag was led by President Jones. ROLL CALL Present: Members Bolton, Bowers, Davis, Moroski, President Jones (5) Absent: Members Bates, Messer (2) Superintendent Catherine L. Mitchell was present. MINUTES APPROVED Mr. -

2017-2018 Annual Report

2017-2018 ANNUAL REPORT Our mission is to ensure that Cincinnati Public Schools students participate in activities beyond the classroom that help them develop the skills they need to succeed in life. Board of Trustees Administrative Staff Program Staff Board Officers Brian Leshner, Executive Director Rachel Stallings, Grant & Program Director Dick Friedman, President Sally Grimes, Development & Marketing Director Armand Tatum, AAA Pathway Manager Barry Lucas, Treasurer Latricia Jones, Business Manager Kyle Vismara, KISR! Enrichment Coordinator Bob Bedinghaus, Secretary Ellen van Treeck, Accountant Board Members at Large Steven Edwards, Administrative Assistant Resource Coordinators Roselawn Condon Charley Frank Sev Sheets, Intern Darcus Anderson, Woodford Paideia Academy Carol Gibbs Felicia Anderson, Aiken New Tech High School Brandon Holmes Extracurricular Directors Dana Bierman, ABC High School Athletic Director College Hill Fundamental Academy Wayne Box Miller Jonas Smith, Tracy Bishop, & Withrow University High School A.D. Frederick Douglass School Jay Richey Sheena Dunn, Paul Brownfield, Aiken New Tech High School Carson School Alex Stillpass Jamell Taylor, Steve Ellison, Walnut Hills High School Silverton Paideia Academy Lisa Thal Linda Johnson-Towles, Clark Montessori High School Jeff Wiles, Shelby Zimmer, Winton Hills Academy Andrew Mueller, Hughes STEM High School Jabreel Moton, Woodward Career Tech High School 21st Century CLC Program P.J. Pope, Shroder High School Kim Ronnebaum, Winton Hills Academy Phillip O’Neal, Western Hills/Dater High School Romell Salone, Taft I.T. High School Rothenberg Rooftop Garden Bryna Bass, Outdoor Classroom Educator Julie Singer, Volunteer Coordinator From opportunity comes leadership Leadership. Self-assurance. Responsibility. Time Management. Teamwork. Resilience. According to numerous studies, these are just some of the skills that children learn by participating in extracurricular activities. -

2021-22 CPS High School Guide

Welcome Your future awaits Cincinnati Public Schools 2021 2022 High School Guide 1 School Year Opening Doors to a World of Possibilities Hello CPS Students and Families, How to use this Guide This handy High School Guide will help you with the big Welcome to high school! decision: Which high school is best for me? Here in Cincinnati Public Cincinnati Public Schools offers 16 high schools with a variety of Schools, our high schools are programs that you can match to your interests and goals — and focused on preparing students which allow you to graduate prepared to enter college, the military for success — whether their or the workforce. paths take them to two- or Our high schools and program options are described inside. Study four-year colleges, into the this Guide with your family, and you’ll be ready to enter the online military or into the workforce. high school lottery. We’re making CPS a District of Destination — our families’ best choice for education. High School Application Lottery Period for 2021-22 Submit online applications to High School Lottery: We want our students to exceed Ohio’s rigorous graduation requirements, but we also want them graduating with clear plans January 12, 2021 through April 16, 2021 in their heads for their futures. How the online high school lottery works: • Select in order of preference, with We use an online lottery application to assign CPS students to three high schools number one being your top choice (in case your top choice high schools.* is filled). For lottery details and to see what each CPS high school offers, • The lottery assigns seats in high schools based on preference take some time to study this High School Guide as a family, order and space available. -

Withrow High School Celebrates 100 Years of Excellence in Epic Fashion

Withrow Alumni • Box 8186 • Cincinnati, OH 45208 (513) 363-9085 [email protected] Spring 2013 Withrow Alumni • Box 8186 • Cincinnati, OH 45208 • (513) 363-9085 • withrowalumni.org Fall 2019 Withrow High School Celebrates 100 Years of Excellence in Epic Fashion by NICHELLE BOLDEN ’84 After two years of organiza- School was honored by city, tion, meeting, planning, and ex- county, and state officials with ecution, the Withrow Cen- proclamations officially declar- tennial Celebration took place ing Withrow Weekend through- from September 4 through Sep- out the city. City councilman Jeff tember 8, 2019. Presented by Pastor (’01) delivered the first of- the Withrow Alumni Associa- ficial proclamation from the tion, the five-day celebration Mayor’s office, followed by marked our 100 years of provid- Hamilton County Commis- ing excellence in educational, sioner Denise Driehaus and State civic, musical and athletic ac- Representatives Brigid Kelly and complishments. Additionally, The gala committee delivered a spectacular evening. Sedrick Denson. Finally, Tiger long-standing community and corporate partners, Western alumnus, State Senator Cecil Thomas, presented WAI with & Southern Financial Group, the Cincinnati Herald, Frost, proclamations from the Ohio Senate and an official guber- Brown and Todd Legal Firm, and Xavier University, joined natorial proclamation from Governor Mike DeWine. For- the Alumni Association in presenting this grand affair. mer Ohio state representative and class of 1989 President Kicking off a host of events was the ORANGE OUT on Alicia Reece served as the Mistress of Ceremonies, as four Fountain Square, where 1,000 Tigers descended upon of Cincinnati’s legendary DJs—Da’Mon George (’88), downtown to commemorate our birthday. -

NOTABLE WITHROW ALUMNI 07/27/2021 Field First Name Last

NOTABLE WITHROW ALUMNI 07/27/2021 Field First Name Last Name Class Career ART Charles Crozier 1942 Painter, greeting card designer; cartoonist at Withrow ART Robert Fabe 1935 Noted Cincinnati artist, Professor of Fine Arts at UC 1958-1987, Honored by City of Cincinnati, May, 1997 (WHoF) ART Ed Fern 1927 Well known portrait painter, later known for Hawaiian paintings; cartoonist at Withrow ART Owen Findsen 1953 Cincinnati Enquirer Art critic; Author, cartoonist at Withrow ART Franklin Folger 1937 Nationally syndicated cartoonist “The Girls” ART J. William Kennedy 1921 Noted painter, Professor of Art at University of Illinois; painting hangs at Withrow ART Bates Lowry 1941 Architecture historian, Founding director National Building Museum, Author ART William Melvin 1947 Aviation artist ART David Niland 1948 Internationally known architect, professor at UC ART Elmer Ruff 1960 Cincinnati artist and teacher ART John Ruthven 1943 American Artist, Wildlife, 2004 National Medal of Arts; cartoonist at Withrow (WHoF) ART Dave Snyder 1971 Famous Car artist ART Warren Stichtenoth 1943 Noted Cincinnati artist, career in commercial art and advertising ART Tom Wesselmann 1949 Internationally known “Pop” artist ($10.7 million for one painting in 2008) (WHoF) AUTHORS Nancy Stine Boyles 1964 “Parenting a Child with Attention Deficit” AUTHORS James Clingman 1963 Award winning columnist, "Blackonomics", "Black Dollars Matter" AUTHORS William L. Cramer 1942 “Air Combat with the Mighty 8th: A Teenage Warrior in World War II AUTHORS Greg Dees 1968 “Enterprising Nonprofits” “The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship” AUTHORS Duncan Dieterly 1957 “Short Stories One” AUTHORS Ralph Friedrich 1929 Faculty, Poet and translator “Boy at Dusk” AUTHORS Benjamin Gorman 1994 Educator, "The Sum of Our Gods", "Corporate High School" AUTHORS Shirley Motter Linde 1947 “Healthy Homes in a Toxic World” AUTHORS Robert Lowry 1937 Postwar Novelist, winner of O. -

University of Cincinnati News Record. Friday, October 25, 1968. Vol. LVI

Which One~Wil.R,ign Over Homecoming' 681 . JUDY RATCLIFF of Delta Delta KATHY PARCHMAN, a sopho- MARY MARGARET DEWAN KATHY BERTKE, representing BONNIE SALMANS" studying Delta is a sophomore in more studying Art Education in of Kappa Delta is a sophomore Scioto Hall, isa sophomore in Interior Design in DAA, Elementary Education who works DAA, is a member of Kappa theater major who. works as University College whose hobbies represents Chi Omega. Bonnie lists with retarded children. Kappa Gamma and YF A. WFIB's Assistant News Director. include sewing and cooking. swimming among her interests. ,.J ~\CEN""'~ . fUC~\ University of Cincinnati NEW·S .RECORD Published Tuesdays and Fridays during the Academic Year except as scheduled. ~~150X~ ., ~ ~'19 _196 Vol. 56 Cincinnati, Ohio' Friday, October 25, 1968 No. 7 ? Appropriation OfPower Tightens Senate Control by Patrick J. Fox of the .Student Senate. The Executive News Editor Speaker: will not, though, losethe , In a meeting highlighted by the privileges given to him by his passing of four. amendments' to Senate position. ' t he Senate constitution and The same amendment redefined by-laws, the Senate 'Voted itselt the qualifications for officers of the power to make all University Senate assuch:' Boards under their power to "The Student Body President comply to. any and all pertaining must be an undergraduate day- Senate legislation. student and must have attended .. Til-ispiece of legislation was part the . University as a full-time of the amendment to Article III undergraduate day student for not of the by-laws which put the less' than eight academic or co-op Orientation Board,' Publications quarters prior to taking office." Board, Activities Board, Budget "The Vice President of the Board, Elections Board, and Student Body must' be an University Center Board under the undergraduate day-student and supervision of the Student Body must have attended the University for not less than five .acadernic or President. -

CPS High School Guide 2020-21

High School Guide 2020-2021 Welcome Your future awaits Enrolled Enlisted Employed YOUR DISTRICT OF DESTINATION 1 Opening Doors to a World of Possibilities Message from the Superintendent How to use this Guide This handy High School Guide will help you with the big decision: Which high school is best for me? Cincinnati Public Schools offers 16 high schools with a variety of programs that you can match to your interests and goals — and which allow you to graduate prepared to enter college, the military or the workforce. Our high schools and program options are described inside. Study this Guide with your family, and you’ll be ready to enter the online high school lottery and select five high schools in order of preference. The lottery randomly assigns seats based on the preference order and space available. Remember — Round 1 of the high school lottery is January 7 to February 21, 2020. Hello CPS Students and Families, Submitting a lottery application anytime during Round 1 gives you Welcome to high school! the best chance of getting into your first-choice high school. Here in Cincinnati Public Schools, our high schools are focused on Want to take a tour before you decide? Go the high school’s preparing students for success — whether their paths take them to website and click on the Enroll tab for contact information. two- or four-year colleges, into the military or into the workforce. cps-k12.org We’re making CPS a District of Destination — our families’ best For details about the high school lottery, choice for education. -

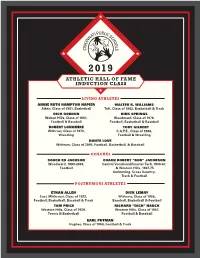

Class of 2019

2019 ATHLETIC Hall OF FaME INDUCTION ClaSS LIVING ATHLETES ANNIE RUTH HAMPTON NAPIER WALTER R. WILLIAMS Aiken, Class of 1981, Basketball Taft, Class of 1962, Basketball & Track DICK GORDON KIRK SPRINGS Walnut Hills, Class of 1961, Woodward, Class of 1976, Football & Baseball Football, Basketball & Baseball ROBERT LONGMIRE TOBY GILBERT Withrow, Class of 1973, C.A.P.E., Class of 1986, Wrestling Football & Wrestling DANTE LOVE Withrow, Class of 2005, Football, Basketball, & Baseball COACHES COACH ED JACKSON COACH ROBERT “BOB” JACOBSON Woodward, 1990-2003, Central Vocational/Courter Tech, 1958-67, Football & Western Hills, 1967-75 Swimming, Cross Country, Track & Football POSTHUMOUS ATHLETES ETHAN ALLEN DICK LEMAY East (Withrow), Class of 1922, Withrow, Class of 1956, Football, Basketball, Baseball & Track Baseball, Basketball & Football TOM PRICE RICHARD “DICK” HAUCK Western Hills, Class of 1939, Western Hills, Class of 1947, Tennis & Basketball Football & Baseball EARL PUTMAN Hughes, Class of 1950, Football & Track WELCOME TO THE 2019 CPS ATHLETIC HALL OF FAME INDUCTION CEREMONY HOSTED BY PRESENTED BY THURSDAY, APRIL 18, 2019 SOCIal HOUR: 5PM | BANQUET: 6PM INDUCTION CEREMONY: 7PM MasteRS OF CERemoNY John Popovich, Sports Director WCPO Channel 9 Lincoln Ware, SOUL 101.5 LIVING Athlete INDUctees Annie Ruth Napier, Aiken Dick Gordon, Walnut Hills High School Robert Longmire, Withrow High School Walter Williams, Taft High School Kirk Springs, Woodward High School Toby Gilbert, C.A.P.E. Dante2018 Love, Withrow High School coach INDUctees Ed -

Minutes Business Board Meeting

May 24 2021 BOARD OF EDUCATION CINCINNATI, OHIO PROCEEDINGS BUSINESS MEETING May 24, 2021 Table of Contents Roll Call . 705 48 Hour Waiver to Amend the Agenda to Include the Following Changes: Board Matters will be introduced after Hearing of the Public; Announcements will follow Board Matters; the Addition of a Special Announcement; Resolutions will follow Announcements; and Two Resolutions: 1.) A Resolution to Appoint Tianay Amat as Interim Superintendent 2.) A Resolution Accepting the Amounts and Rates as Determined by the Budget Commission and Authorizing the Necessary Tax Levies and Certifying them to the County Auditor . 705 Minutes Approved . 705 Report of the Student Achievement and District Instructional Performance Committee May 7, 2021 . 706 Presentations . 714 Announcement/Hearing of the Public . 714 Board Matters . 715 A Resolution to Appoint Tianay Amat as Interim Superintendent . 715 A Resolution Thanking the City of Cincinnati Department of Health for Partnering with Cincinnati Public Schools During the Covid-19 Crisis . 716 A Revised Resolution Authorizing 2021-2022 Membership in the Ohio High School Athletic Association (OHSAA) . 717. Fiscal Year 2020-2021 Amended Appropriations Resolution . 718 A Resolution Accepting the Amounts and Rates as Determined by the Budget Commission and Authorizing the Necessary Tax Levies and Certifying them to the County Auditor . 720 Report of the Superintendent Recommendations of the Superintendent of Schools . 1. Certificated Personnel . 724 2. Civil Service Personnel . 735 Report of the Treasurer I. Financial News . 742 II. Treasurer Authority . 743 III. Agreements . 743 IV. Amendment to Agreements . 746 V. Award of Purchase Orders . 754 VI. Payments . 756 VII. Then and Now Certificates. -

View of the City's History in Suitable Way to Communicate Our Appreciation, to Express 1982 with Cincinnati: the Queen City, Which Continues Our Gratitude

Winter 1984 Annual Report 1984 89 Annual Report 1984 Report of the President 1984 Annual Meeting John Diehl President President John Diehl called the 1984 Annual Meeting of The Cincinnati Historical Society to order at The Cincinnati Historical Society has enjoyed, 8:23 p.m. on January 9, 1985. He asked the Director, in 1984, the best year in its more than a century and a half Gale Peterson, to serve as secretary for the meeting and existence. Our financial condition is healthy. Individual obtained the consent of the membership for dispensing membership has exceeded the 3,000-mark for the first time. with reading the Minutes of the previous meeting. Business membership continues to grow in proportion. We Mr. Diehl provided a brief report on develop- are reaching more people and demonstrating our steadily ments during the past year in which he noted that the growing usefulness to the community. Society's membership had surpassed 3,000 for the first time. Added growth makes our already critical The President then commented on the space problem more acute. Much of the time of the Board is revised Constitution that was being submitted to the spent on the alleviation of this problem. In close harmony membership for ratification. The new Constitution had and cooperation with the Board of the Museum of Natural been approved by the Board of Trustees which recommended History, we are diligently exploring the possibilities of a its approval, and the text was published and distributed Heritage Center, to be located in Union Terminal. This to the membership with the Fall Newsletter. -

A Summary of One Hundred Years of Withrow History 1920 in September 1919 the New East High School Opened to Students in Grades Nine Through 12

A Summary of One Hundred Years of Withrow History 1920 In September 1919 the new East High School opened to students in grades nine through 12. There were no clocks in the Tower, no lockers in the halls and although the cafeteria was up and running, students had to bring their own knives and forks. The football stadium was incomplete and there was no football field so the fledgling Tigers had to play all their games away. Mr. Edmund D. Lyon, who had been principal at both Woodward and Hughes High Schools, was named principal of the new East High. Mr. Lyon remained as principal until his retirement in 1933. 1921 Students at East High publish and print a bi-weekly student newspaper, The Tower News. It is the only public high school newspaper in the City of Cincinnati. Containing articles about athletics, school clubs and activities, and stories and poems written by students, the paper also had an agricultural report. Agricultural subjects were part of the East High curriculum at that time. The large Wulsin estate, which adjoined East High on the west, was classified as a working farm up until its sale in 1967 and the construction of the Regency high rise and townhouses. 1922 The completed football stadium was opened for the East High vs Hughes High game in October 1921. 8,000 people attended the game, the largest high school attendance ever in Cincinnati. The stadium was built to hold approximately 10,000 so some seats were still available. The rivalry with Hughes , which many East High students would have attended but for the creation of East High, was paramount.