MONTAIGNE and the TRIAL of SOCRATES Author(S): Eric Macphail Source: Bibliothèque D'humanisme Et Renaissance, T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Faith-Healing New Secular Humanist Centers?

New Secular More on Humanist Faith-Healing Centers? James Randi Paul Kurtz Gerald Larue Vern Bullough Henry Gordon Bob Wisne David Alexander Faith-healer Robert Roberts Also: Is Goldilocks Dangerous? • Pornography • The Supreme Court • Southern Baptists • Protestantism, Catholicism, and Unbelief in France 1n Its Tree _I FALL 1986, VOL. 6, NO. 4 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 17 BIBLICAL SCORECARD 62 CLASSIFIED 12 ON THE BARRICADES 60 IN THE NAME OF GOD 6 EDITORIALS Is Goldilocks Dangerous? Paul Kurtz / Pornography, Censorship, and Freedom, Paul Kurtz I Reagan's Judiciary, Ronald A. Lindsay / Is Secularism Neutral? Richard J. Burke / Southern Baptists Betray Heritage, Robert S. Alley / The Holy-Rolling of America, Frank Johnson 14 HUMANIST CENTERS New Secular Humanist Centers, Paul Kurtz / The Need for Friendship Centers, Vern L. Bullough / Toward New Humanist Organizations, Bob Wisne THE EVIDENCE AGAINST REINCARNATION 18 Are Past-Life Regressions Evidence for Reincarnation? Melvin Harris 24 The Case Against Reincarnation (Part 1) Paul Edwards BELIEF AND UNBELIEF WORLDWIDE 35 Protestantism, Catholicism, and Unbelief in Present-Day France Jean Boussinesq MORE ON FAITH-HEALING 46 CS ER's Investigation Gerald A. Larue 46 An Answer to Peter Popoff James Randi 48 Popoff's TV Empire Declines .. David Alexander 49 Richard Roberts's Healing Crusade Henry Gordon IS SECULAR HUMANISM A RELIGION? 52 A Response to My Critics Paul Beattie 53 Diminishing Returns Joseph Fletcher 54 On Definition-Mongering Paul Kurtz BOOKS 55 The Other World of Shirley MacLaine Ring Lardner, Jr. 57 Saintly Starvation Bonnie Bullough VIEWPOINTS 58 Papal Pronouncements Delos B. McKown 59 Yahweh: A Morally Retarded God William Harwood Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Doris Doyle, Steven L. -

Ancient Narrative Volume 6

Maecenas and Petronius’ Trimalchio Maecenatianus SHANNON N. BYRNE Xavier University This paper examines Petronius’ use of Maecenas as a model for specific behaviors and traits that Trimalchio exhibits throughout the Cena. At first glance Seneca’s distinct portrait of an effeminate Maecenas ruined by his own good fortune seems to have informed Petronius’ characterization of Trimalchio. I have argued elsewhere that the target of Seneca’s intense criti- cism of Maecenas was not Augustus’ long-dead minister, but rather a con- temporary who had replaced Seneca in influence at court; someone whose character and tastes were wanton compared to Seneca’s; someone who en- couraged Nero’s less savory tendencies instead of keeping them hidden or in check as Seneca and Burrus had tried to do; someone who resembled Mae- cenas in character and literary enthusiasm; in short, someone very much like Petronius himself. Petronius understood the implications in Seneca’s attacks on Maecenas, and as if to stamp approval on the fact that he and Maecenas were indeed alike in many ways, Petronius took pleasure in endowing his decadent freedman with the very qualities that Seneca meant to be demean- ing.1 Although my focus is on Maecenas, it is obvious that Petronius spared no effort in rounding out Trimalchio and all the freedmen at the banquet with mannerisms and conduct that would recall memorable literary characters in works from Plato’s Symposium to Horace’s Cena Nasidiensi and beyond.2 ————— 1 For a discussion regarding Seneca’s attacks on Maecenas and the argument that Petronius was their intended victim, see Byrne 2006, 83–111. -

D. Octavius Caesar Augustus (Augustus) - the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Volume 2

D. Octavius Caesar Augustus (Augustus) - The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 2. C. Suetonius Tranquillus Project Gutenberg's D. Octavius Caesar Augustus, (Augustus) by C. Suetonius Tranquillus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: D. Octavius Caesar Augustus (Augustus) The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 2. Author: C. Suetonius Tranquillus Release Date: December 13, 2004 [EBook #6387] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK D. OCTAVIUS CAESAR AUGUSTUS *** Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS By C. Suetonius Tranquillus; To which are added, HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. D. OCTAVIUS CAESAR AUGUSTUS. (71) I. That the family of the Octavii was of the first distinction in Velitrae [106], is rendered evident by many circumstances. For in the most frequented part of the town, there was, not long since, a street named the Octavian; and an altar was to be seen, consecrated to one Octavius, who being chosen general in a war with some neighbouring people, the enemy making a sudden attack, while he was sacrificing to Mars, he immediately snatched the entrails of the victim from off the fire, and offered them half raw upon the altar; after which, marching out to battle, he returned victorious. -

The Shakespeare Library. General Editor Professor I

THE SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. GENERAL EDITOR PROFESSOR I. GOLLANCZ, Lxr'r.D. SHAKESPEARE'S PLUTARCH Thts S_ectal Edttton of' SHAXESrZ^xZ'S PLtrr^RCX_ ' ts hmtted to I ooo coptcs, o _'btcb 500 are reser,ved for .dmertca. THE LIVES OF THE NOBLE GRE- --. CLANS AND ROMANES, CO\IPARED t_,_ther b.: that Uaue learned "l>hu_I_.phcrand ] h,tortv_ra- "l'ranPate, domofCrcckcunol-rc_h_, I _.,,. _ A_._',,'_,_b_o_ofl_cllo_ane_ Bu,hopo! Aux.-'rre,om.of lh_.Mr_gl,mU', cotu_:',a_ ,, ,.:._ : Amn_.'r of 1_aualce,andout of l-r_nd, v_tuI.' gh;,,;,,. • ,--- ) lm_la Lon&l_hnn byV.V_"ThomaLV_ma'oulli$ ";_, 'i S HAKESPEAR E'S "_PLUTARCH :EDITED BY C. F. TUCKER BROOKE B.LiTT. : VOL. I. : CONTAI_INO THE MAIN SOURCES OF JULIUS CAESAR t _, I _ , NEW YORK DUFFIELD & COMPANY LONDON: CHATTO & WINDUS :9o9 / / , • f , E INDIANA UN'I_TBS_._I" lIBRARY All ri_t_ reler_¢d INTRODUCTION r_ THE influence of the writings of Plutarch of Chmronea on English literature might well be made the subject of one of the most interesting chapters in the long story of the debt of moderns to ancients. One of the most kindly and young spirited, he is also one of the most versatile of Greek writers, and his influence has worked by devious ways to the most varied results. His treatise on the Education of Children had the honour to be early translated into the gravely charming prose of Sir Thomas Elyot, and to be published in a black- letter quarto 'imprinted,' as the colophon tells us, 'in Fletestrete in the house of Thomas Berthelet.' The same work was drawn upon unreservedly by Lyly in the second part of Euphues, and its teachings reappear a little surprisingly in some of the later chapters of Pamela. -

Oliver Stoll

Stoll_01_Text_D_20080616:Jahrbuch_Neu 17.06.2008 8:18 Uhr Seite 217 OLIVER STOLL LEGIONÄRE, FRAUEN, MILITÄRFAMILIEN UNTERSUCHUNGEN ZUR BEVÖLKERUNGSSTRUKTUR UND BEVÖLKERUNGSENTWICKLUNG IN DEN GRENZPROVINZEN DES IMPERIUM ROMANUM* Die Legionen Roms als Katalysatoren demographischer Frauen um das Militär und »Militärfamilien« – Entwicklung ........................217 der Sog der Legionen . ................262 Vorbemerkungen zur Methode, notwendige Vorbemerkung: Frauen und Familien um das Militär – Definitionen, hingenommene Einschränkungen und ein Randphänomen? . ................262 Grenzen, Ziele, Chancen und Fragen . ......217 Offiziers- und Beamtenfrauen .............264 Rekrutierung in die Legionen am Niederrhein und am »Militärfamilien« – bunte Vielfalt und Mobilität: obergermanisch-rätischen Limes und Siedlungsverhalten Ehefrauen, Konkubinen, Soldatenmütter, Soldaten- der Legionsveteranen ..................223 töchter, Sklavinnen und Prostituierte ..........270 Militärhistorische Voraussetzungen: die Statio nierungs- »Gruppenbild mit Dame« – ein kurzer Blick auf und Dislokationsgeschichte der Legionen in den Grabmonumente mit der Darstellung von Militär- beiden germanischen Provinzen und Raetien . 224 familien aus den Limeszonen des Imperium Alte Ergebnisse – neue Zeugnisse: der epigraphische Romanum.......................286 Befund zur Rekrutierung und dem Siedlungsverhalten der Veteranen...................228 Fazit und Epilog . ................325 Germania inferior .................230 Literatur ..........................335 Germania -

In Search of the Dark Ages in Search of the Dark Ages

IN SEARCH OF THE DARK AGES IN SEARCH OF THE DARK AGES Michael Wood Facts On File Publications New York, New York Oxford, England For my mother and father IN SEARCH OF THE DARK AGES Copyright © 1987 by Michael Wood All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the pub lisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wood, Michael. In search of the Dark Ages. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Great Britain—History—To 1066. 2. England— Civilization—To 1066. 3. Anglo-Saxons. I. Title. DA135.W83 1987 942.01 86-19839 ISBN 0-8160-1686-0 Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Genealogy Table 10 CHAPTER 1 13 Boadicea CHAPTER 2 37 King Arthur CHAPTER 3 61 The Sutton Hoo Man CHAPTER 4 77 Offa CHAPTER 5 104 Alfred the Great CHAPTER 6 126 Atheistan CHAPTER 7 151 Eric Bloodaxe CHAPTER 8 177 Ethelred the Unready CHAPTER 9 204 William the Conqueror Postscript 237 Book List 243 Picture Credits 244 Index 245 Acknowledgements I must first thank the staffs of the following libraries for their kindness and helpfulness, without which this book would not have been possible: Corpus Christi College Cambridge, Jesus College Oxford, the Bodleian Library Oxford, the Cathedral Library Durham, the British Library, Worcester Cathedral Library, the Public Record Office, and the British Museum Coin Room. I am indebted to Bob Meeson at Tamworth, Robin Brown at Saham Toney and Paul Sealey at Colchester Museum, who were all kind enough to let me use their unpublished researches. -

Plutarch's Lives

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives (Dryden trans.) vol. 4 [1906] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

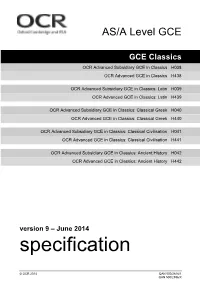

Specification – OCR AS/A Level Classics

AS/A Level GCE GCE Classics OCR Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Classics H038 OCR Advanced GCE in Classics H438 OCR Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Classics: Latin H039 OCR Advanced GCE in Classics: Latin H439 OCR Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Classics: Classical Greek H040 OCR Advanced GCE in Classics: Classical Greek H440 OCR Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Classics: Classical Civilisation H041 OCR Advanced GCE in Classics: Classical Civilisation H441 OCR Advanced Subsidiary GCE in Classics: Ancient History H042 OCR Advanced GCE in Classics: Ancient History H442 version 9 – June 2014 specification © OCR 2014 QAN 500/2616/1 QAN 500/2596/X Contents 1 About these Qualifications 4 1.1 The Two-Unit AS 4 1.2 The Four-Unit Advanced GCE 5 1.3 Qualification Titles and Levels 5 1.4 Aims 6 1.5 Prior Learning/Attainment 6 1.6 Pathways 7 2 Summary of Content 11 2.1 AS Units 11 2.2 A2 Units 12 3 Unit Content 14 3.1 AS Unit L1 (Entry Code F361): Latin Language 14 3.2 AS Unit L2 (Entry Code F362): Latin Verse and Prose Literature 15 3.3 AS Unit G1 (Entry Code F371): Classical Greek Language 16 3.4 AS Unit G2 (Entry Code F372): Classical Greek Verse and Prose Literature 17 3.5 AS Unit CC1 (Entry Code F381): Archaeology: Mycenae and the classical world 18 3.6 AS Unit CC2 (Entry Code F382): Homer's Odyssey and Society 19 3.7 AS Unit CC3 (Entry Code F383): Roman Society and Thought 21 3.8 AS Unit CC4 (Entry Code F384): Greek Tragedy in its context 22 3.9 AS Unit CC5 (Entry Code F385): Greek Historians 24 3.10 AS Unit CC6 (Entry Code F386): City Life in Roman Italy 25 3.11 -

Bello-Gallico.Pdf

DE BELLO GALLICO Caius Julius Caesar 2 De Bello Gallico and Other Commentaries Caius Julius Caesar ii Contents INTRODUCTION v 1 BOOK I 1 2 BOOK II 33 3 BOOK III 51 4 BOOK IV 67 5 BOOK V 87 6 BOOK VI 117 7 BOOK VII 141 8 BOOK VIII 189 9 THE CIVIL WAR BOOK I 217 10 BOOK II 261 11 BOOK III 287 12 INDEX 345 iii iv CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BY THOMAS DE QUINCEY The character of the First Caesar has perhaps never been worse appreciated than by him who in one sense described it best; that is, with most force and eloquence wherever he really did comprehend it. This was Lucan, who has nowhere exhibited more brilliant rhetoric, nor wandered more from the truth, than in the contrasted portraits of Caesar and Pompey. The famous line, “Nil actum reputans si quid superesset agendum,” is a fine feature of the real char- acter, finely expressed. But, if it had been Lucan’s purpose (as possibly, with a view to Pompey’s benefit, in some respects it was) utterly and extravagantly to falsify the character of the great Dictator, by no single trait could he more effectually have fulfilled that purpose, nor in fewer words, than by this expres- sive passage, “Gaudensque viam fecisse ruina.” Such a trait would be almost extravagant applied even to Marius, who (though in many respects a perfect model of Roman grandeur, massy, columnar, imperturbable, and more perhaps than any one man recorded in History capable of justifying the bold illustra- tion of that character in Horace, “Si fractus illabatur orbis, impavidum ferient ruinae”) had, however, a ferocity in his character, and a touch of the devil in him, very rarely united with the same tranquil intrepidity. -

Dio's Rome an Historical Narrative Originally Composed in Greek

Dio's Rome An Historical Narrative Originally Composed in Greek During the Reigns of Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus; And Now Presented in English Form. Second Volume Extant Books 36-44 (B.C. 69-44). Cassius Dio The Project Gutenberg EBook of Dio's Rome, by Cassius Dio This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Dio's Rome An Historical Narrative Originally Composed in Greek During the Reigns of Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla, Macrinus, Elagabalus and Alexander Severus; And Now Presented in English Form. Second Volume Extant Books 36-44 (B.C. 69-44). Author: Cassius Dio Release Date: March 17, 2004 [EBook #11607] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DIO'S ROME *** Produced by Ted Garvin, Jayam Subramanian and PG Distributed Proofreaders DIO'S ROME AN HISTORICAL NARRATIVE ORIGINALLY COMPOSED IN GREEK DURING THE REIGNS OF SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS, GETA AND CARACALLA, MACRINUS, ELAGABALUS AND ALEXANDER SEVERUS: AND Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. NOW PRESENTED IN ENGLISH FORM BY HERBERT BALDWIN FOSTER, A.B. (Harvard), Ph.D. (Johns Hopkins), Acting Professor of Greek in Lehigh University SECOND VOLUME _Extant Books 36-44 (B.C. 69-44)_. 1905 PAFRAETS BOOK COMPANY TROY NEW YORK VOLUME CONTENTS Book Thirty-six Book Thirty-seven Book Thirty-eight Book Thirty-nine Book Forty Book Forty-one Book Forty-two Book Forty-three Book Forty-four DIO'S ROMAN HISTORY 36 Metellus subdues Crete by force (chapters 1, 2)[1] Mithridates and Tigranes renew the war (chapter 3). -

Plutarch's Lives

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives (Dryden trans.) vol. 5 [1906] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Eutropius, Brevarium, 7.1–7

Eutropius, Brevarium, 7.1–7 1 AFTER the assassination of Caesar, in about the seven hundred and ninth year of the city, the civil wars were renewed; for the senate favored the assassins of Caesar; and Antony, the consul, being of Caesar's party, endeavored to crush them in a civil war. The state therefore being thrown into confusion, Antony, perpetrating many acts of violence, was declared an enemy by the senate. The two consuls, Pansa and Hirtius, were sent in pursuit of him, together with Octavianus, a youth of eighteen years of age, the nephew of Caesar,1 whom by his will he had appointed his heir, directing him to bear his name; this is the same who was afterwards called Augustus, and obtained the imperial dignity. These three generals therefore marching against Antony, defeated him. It happened, however, that the two victorious consuls lost their lives; and the three armies in consequence became subject to Caesar only. 2 Antony, being routed, and having lost his army, fled to Lepidus, who had been master of the horse to Caesar, and was at that time in possession of a strong body of forces, by whom he was well received. By the mediation of Lepidus, Caesar shortly after made peace with Antony, and, as if with intent to avenge the death of his father, by whom he had been adopted in his will, marched to Rome at the head of an army, and forcibly procured his appointment to the consulship in his twentieth year. In conjunction with Antony and Lepidus he proscribed the senate, and proceeded to make himself master of the state by arms.