Managing Racist Pasts: the Black Justice League's Demand For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JULIA BUMKE Local Address: Permanent Address: [email protected] 15 Irving Street, Apt

JULIA BUMKE Local Address: Permanent Address: [email protected] 15 Irving Street, Apt. 2 362 Morris Ave. 201.486.7197 Somerville, MA 02144 Mountain Lakes, NJ 07046 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Institute for Advanced Theater Training at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA | American Repertory Theater/Moscow Art Theater School. M.F.A. Candidate | Dramaturgy and Theater Studies, June 2015. Princeton University, Princeton, NJ. A.B., Magna cum laude | United States History, with Theater and American Studies concentrations, June 2013. • Academic Senior Thesis, From Upstarts to Institutions: How W. McNeil Lowry Transformed America’s Nonprofit Theaters. Sean Wilentz, Advisor. • Creative Independent Thesis, Program in Theater: Directed Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park With George, Berlind Theatre, McCarter Theater Center. Tim Vasen, Advisor. HONORS AND PUBLICATIONS • Francis LeMoyne Page Theater Award | Princeton University Program in Theater, Spring 2013. • Asher Hinds Prize for Excellence in American Studies | Princeton University Program in American Studies, Spring 2013. • Published What History Can Teach Us About Arts Philanthropy in the Age of Obama | HowlRound: Journal of the Theater Commons at Emerson College, January 2013. • Published Rock ’n’ Revolution: How the Prague Spring’s Cultural Liberalism Transformed Czech Human Rights | -

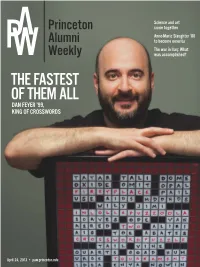

The Fastest of Them

00paw0424_coverfinalNOBOX_00paw0707_Cov74 4/11/13 10:16 AM Page 1 Science and art Princeton come together Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 Alumni to become emerita The war in Iraq: What Weekly was accomplished? THE FASTEST OF THEM ALL DAN FEYER ’99, KING OF CROSSWORDS April 24, 2013 • paw.princeton.edu PAW_1746_AD_dc_v1.4.qxp:Layout 1 4/2/13 8:07 AM Page 1 Welcome to 1746 Welcome to a long tradition of visionary Now, the 1746 Society carries that people who have made Princeton one of the promise forward to 2013 and beyond with top universities in the world. planned gifts, supporting the University’s In 1746, Princeton’s founders saw the future through trusts, bequests, and other bright promise of a college in New Jersey. long-range generosity. We welcome our newest 1746 Society members.And we invite you to join us. Christopher K. Ahearn Marie Horwich S64 Richard R. Plumridge ’67 Stephen E. Smaha ’73 Layman E. Allen ’51 William E. Horwich ’64 Peter Randall ’44 William W. Stowe ’68 Charles E. Aubrey ’60 Mrs. H. Alden Johnson Jr. W53 Emily B. Rapp ’84 Sara E. Turner ’94 John E. Bartlett ’03 Anne Whitfield Kenny Martyn R. Redgrave ’74 John W. van Dyke ’65 Brooke M. Barton ’75 Mrs. C. Frank Kireker Jr. W39 Benjamin E. Rice *11 Yung Wong ’61 David J. Bennett *82 Charles W. Lockyer Jr. *71 Allen D. Rushton ’51 James K. H. Young ’50 James M. Brachman ’55 John T. Maltsberger ’55 Francis D. Ruyak ’73 Anonymous (1) Bruce E. Burnham ’60 Andree M. Marks Jay M. -

Managing Racist Pasts the Black Justice League’S Demand for Inclusion and Its Challenge to the Promise of Diversity at Princeton University

Managing Racist Pasts the Black Justice League’s Demand for Inclusion and Its Challenge to the Promise of Diversity at Princeton University Tomoyo Joshi Submitted to the Institute of Gender, Sexuality & Feminist Studies of Oberlin College In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................ II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................ III INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 4 METHODS ................................................................................................................................................... 5 WHY IS THIS PROJECT FEMINIST? ..................................................................................................................... 7 LITERATURE REVIEW .................................................................................................................................... 10 PART 1: THE DISCOURSE OF DIVERSITY IN PRINCETON UNIVERSITY’S “MANY VOICES, ONE FUTURE” WEBSITE ............................................................................................................................................. 12 DIVERSITY AS COMMODITY: MINORITY DIFFERENCE IS INDIVIDUALIZED AND CONSUMED ....................................... -

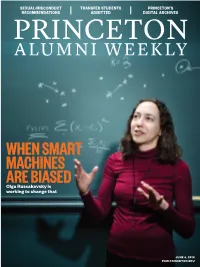

WHEN SMART MACHINES ARE BIASED Olga Russakovsky Is Working to Change That

SEXUAL-MISCONDUCT TRANSFER STUDENTS PRINCETON’S RECOMMENDATIONS ADMITTED DIGITAL ARCHIVES PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY WHEN SMART MACHINES ARE BIASED Olga Russakovsky is working to change that JUNE 6, 2018 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0606-coverFINALrev1.indd 1 5/22/18 10:23 AM That moment you finally get to go through the gates and see the next horizon. Communications of UNFORGETTABLE Office PRINCETON Your support makes it possible. This year’s Annual Giving campaign ends on June 30, 2018. To contribute by credit card, or for more information please call the gift line at 800-258-5421 (outside the US, 609-258-3373), or visit www.princeton.edu/ag. June 6, 2018 Volume 118, Number 14 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 INBOX 3 ON THE CAMPUS 5 Sexual-misconduct recommendations Transfer students Maya Lin visit Class Close-up: Video games deal with climate change A Day With ... dining hall coordinator Manuel Gomez Castaño ’20 Frank Stella ’58 exhibition at PUAM SPORTS: International rowers Championship for women’s crew The Big Three LIFE OF THE MIND 17 Author and professor Yiyun Li Rick Barton on peacemaking PRINCETONIANS 29 Mallika Ahluwalia ’05 Q&A: Yolanda Pierce ’94, first woman to lead Howard University divinity school Tiger Caucus in Congress CLASS NOTES 32 Maya Lin, page 7 Wikipedia Bias and Artificial Intelligence 20 Born Digital 24 ’20; MEMORIALS 49 Olga Russakovsky draws on personal With the decline of paper records, the staff at CLASSIFIEDS 54 experience and technical expertise to help Mudd Library is ensuring that digital records make artificial intelligence smarter. -

Experienceprinceton

ExperiencePrinceton: DIVERSEPERSPECTIVES The Right Will I fit in here? Question to Ask The Right Question As you think about where to go to college, we expect one of the big questions on your mind is this: “Will I fit in here?” Perhaps the question first occurred to you when to Ask you were doing online research or when you visited a college and observed a classroom, talked to a professor, reached out to a current student, went to a dining hall or attended an athletic event. It’s the right question to ask. At Princeton, we work hard to ensure that our students succeed not only academically but also in every other way. Wherever you go on our campus, you will find others who share your values, heritage and interests, as well as those who don’t. And just as important, when you don’t, you will find students and faculty who are interested in what makes you tick and are open to hearing about your experiences. We believe this is the time of your life to grow in every way. While you value where you came from, you no doubt are seeking a learning experience that will take you someplace you have never been — intellectually, emotionally and physically. Our driving philosophy is to ensure an environment where you will be comfortable and challenged. We spend many months seeking students who will help us build a community that is as diverse and intellectually stimulating as possible. Living and learning in such a rich cultural environment will transform your life. Within these pages, you will see how our community comes together. -

2020 Newsletter

Spring 2020 Newsletter Cen bst ter o fo B r . S P e a a h c u e The Mamdouha S. Bobst Center o a n d d m a J u M s t e i c h e T • for Peace and Justice Message from the Director Peaceful Greetings! I am once again very happy to share our exciting news and accomplishments with our friends on campus and across the world. We have had another successful year, even if shortened by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Some of the key highlights include events like “The Politics Police Make: Law Enforcement, State Power and Social Inequality in Democratic States,” workshop organized by Professor Jonathan Mummolo and the Program on Identities and Institutions, and the Race, Ethnicity, and Identity (REI) speaker series, featuring this year Professors Ali Valenzuela and LaFleur Stephens-Dougan, and numerous talks and other activities at the Center. Our visibility on campus continues to grow. Through mid-March, the Bobst Center sponsored over 32 undergraduate student-led activities and initiatives linked to peace and justice across campus. We have also continued to enhance our graduate student grant support to encourage and promote research on themes linked to the mission of the Center. As part of our ongoing collaboration with the American University of Beirut (AUB), we continued with our faculty exchange program and are currently designing new programs that include teaching and study abroad experiences for our undergraduates. We had three AUB faculty members visit and present research at the Center this year. Two of Princeton’s faculty, Erika Kiss and Jan-Werner Müller, taught summer courses at the AUB in 2019. -

SAMUEL STANHOPE SMITH Another Past Princeton President with a Complicated History on Race

L’CHAIM CONFERENCE: THE DEMISE OF CHARISMA: JEWISH LIFE SPRINT FOOTBALL HOW IT BEGAN PRINCETON ALUMNI WEEKLY SAMUEL STANHOPE SMITH Another past Princeton president with a complicated history on race MAY 11, 2016 PAW.PRINCETON.EDU 00paw0511_CovRev1.indd 1 4/27/16 10:58 AM For the most critical questions. No matter how complex your business questions, we have the capabilities and experience to deliver the answers you need to move forward. As the world’s largest consulting fi rm, we can help you take decisive action and achieve sustainable results. www.deloitte.com/answers Audit | Tax | Consulting | Advisory Copyright © 2016 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Consulting May 11, 2016 Volume 116, Number 12 An editorially independent magazine by alumni for alumni since 1900 PRESIDENT’S PAGE 2 Page 32 INBOX 5 FROM THE EDITOR 7 ON THE CAMPUS 13 Inclusivity progress report Panel on Wilson legacy Bogle fellows Tuition, budget for 2016–17 Strategic planning: Regional studies STUDENT DISPATCH: Poker club SPORTS: No more sprint football Road to Rio: Donn Cabral ’12 LIFE OF THE MIND 29 Political parties Hopeful note on climate change GS ’13 Research briefs Elgin P RINCETONIANS 43 Alumnae create web series Conference brings Jewish Katherine alumni back to campus Page 46 Boyer; Q&A: Michael Brown ’87, D. discoverer of planets War Allen story: Fuller Patterson ’38 by CLASS NOTES 51 photo Mr. Boswell Goes to Corsica 32 Samuel Stanhope Smith 38 Base, MEMORIALS 69 The birth of modern political charisma Was Princeton’s seventh president a racist Force CLASSIFIEDS 77 required a candidate with good looks, an or a progressive — and should it make a Air aura of power, and the right PR. -

Time Stamp Sources for Visualization of BBC Broadcast 0:08 Article Covering the Broadcast from the December 10, 1946 Edition Of

Time stamp sources for visualization of BBC Broadcast 0:08 Article covering the broadcast from the December 10, 1946 edition of The Daily Princetonian. Bicentennial Celebration Records (AC148), Box 14, Folder 15. 0:25 Glee Club recording for the broadcast in the Faculty Room of Nassau Hall over long distance telephone to New York, the evening of December 9, 1946 (note the WOR microphone). 1946 Bric-a-Brac. 0:56 Nassau Hall, 1946. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP69, Image No. 2705. 1:10 Students amble down Prospect Street. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box SP06, Image No. 1475. 1:24 Earliest engraving of Nassau Hall, 1760. Nassau Hall Iconography (AC177), Box 1, Folder 1. 1:48 Continental Congress receiving the first Dutch ambassador to the United States, Johan Van Berckel, in Nassau Hall, 1782. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP69, Image No. 2701. 2:04 Faculty Room of Nassau Hall, circa 1930-1950. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP70, Image No. 2760. 2:13 Faculty Room of Nassau Hall, featuring portraits of George Washington and King George II. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP70, Image No. 2747. 2:21 Faculty Room of Nassau Hall. Historical Photograph Collection, Grounds and Buildings Series (AC111), Box MP70, Image No. 2759. 2:49 Dr. Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker. Historical Photograph Collection, Faculty Photographs Series (AC067), Box FAC094. 3:23 Dr. Thomas Jefferson Wertenbaker in precept with students. Historical Photograph Collection, Faculty Photographs Series (AC067), Box FAC094. -

Aas Members of Princeton University's Journalism

A veteran Asia correspondent for a number of out- lets, including CNN, Ressa founded the online Princeton news site Rappler six years ago. Her work has won her honors from her professional peers and from international press freedom organizations. In De- in the service of cember, Time magazine named her one of its Per- sons of the Year. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines called her latest arrest “a shame- free speech less act of persecution by a bully government.” As members of Princeton University’s journalism Discussing her perilous fight for freedom of speech community, we stand in proud solidarity with in her home country, Ressa recently told the Princ- alumna Maria Ressa ‘86 and call on supporters of eton Alumni Weekly: “It’s important to keep rais- Ademocracy everywhere to do the same. ing the alarm when transgressions happen.” Our careers have taken us in many different direc- In that spirit, we call upon government officials, tions. But all of us have practiced or taught journal- policymakers, businesses and private individuals to ism at Princeton. That shared experience made us use whatever leverage they have to press the Philip- understand the importance of intellectual freedom, pine government to cease its harassment of Ressa the free exchange of ideas and the ability to speak and the rest of that country’s press. No person is an truth to power. island in today’s global society; the deprivation of one journalist’s freedom limits access to informa- Those values are what prompt us to speak out on tion for us all. -

A History of Weekly Community Newspapers in the United States

A HISTORY OF WEEKLY COMMUNITY NEWSPAPERS IN THE UNITED STATES: 1900 TO 1980 by BETH H. GARFRERICK A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Communication and Information Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA. ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Beth H. Garfrerick 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This study is an examination of community weekly newspapers in the United States during the period beginning in 1900 and ending in 1980. For this dissertation, the weekly ―community‖ newspaper is defined as a newspaper operating in small towns and rural areas that placed an emphasis on local news. This study analyzes the nature of the weekly community newspaper and how it reflected American society throughout most of the twentieth century. Despite all of the problems that faced the weekly newspaper industry throughout its long and proud history, the constants that remained were survival tactics in terms of reactive versus proactive responses to content, commercial, and professional concerns. Several times throughout the decades an obituary had been written for community weeklies. But they always found a way to fight back and happen upon a means, a method, or a message that resonated with audiences and advertisers enough so as to allow them to keep their doors open for another business day. Community weeklies told the story of average American daily lives more thoroughly and in a more personal manner than the big-city dailies. In essence, the weekly publisher-editor served as author of his community‘s life story. -

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 4 March 11, 2018 4: 30 Lewis Library 134 Introduction 1. President's Report (10 Minut

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 4 March 11, 2018 4: 30 Lewis Library 134 Introduction 1. President’s Report (10 minutes) New Business 1. SGRC Student Proposals: Emily Chen (5 minutes) 2. Projects Board Proposal: Eliot Chen and Isabella Bosetti (5 minutes) 3. Lawnparties Budget Proposal: Liam Glass (10 minutes) 4. Addition to Elections Handbook: Laura Zecca and Jonah Hyman (10 minutes) 5. Ivy League Mental Health Conference Princeton Delegation Princeton: Taylor Pearson, Nourhan Ibrahim, Isaac Treves, Danielle Herman (10 minutes) 6. Communications Strategy Presentation: Tori Gorton (10 minutes) Consent Agenda 1. Confirmation of Communications Committee Members a. Patrycja Pajdak i. Patrycja Pajdak is a member of the class of 2021 from Colonia, NJ, interested in majoring in the Woodrow Wilson School of International Affairs. On campus she’s member of the Mathey College Council Community Development and Communications committees, a member of Girl Up: a campaign of the United Nations Foundation, and a member of the Princeton Polish Society. She’ll be helping with the newsletter and social media in the Communications committee. b. Linh Nguyen i. Hailing from Dallas, Texas, Linh Nguyen is a first-year pursuing a concentration in International Relations Politics and a certificate in the Global Health Program. She has a broad range of interests encompassing orchestral music, economic policy, and everything in between. As a member of the Communications Team, she hopes to use her passion for graphic design and publications to bring more awareness to USG and the crucial issues that the current administration is working to resolve. 2. Confirmation of CCA Committee Members a. -

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 5 March 11, 2018 4: 30 Lewis Library 134

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 5 March 11, 2018 4: 30 Lewis Library 134 Introduction President’s Report (10 minutes) 1. 1 month into the administration 2. Member Highlights a. Thank you to ExComm for a productive meeting on Thursday! b. Thank you Brad for organizing headshots! c. Thank you Olivia Ott for taking initiative with Honor Committee recruiting! d. Thank you Liam Glass for finding exciting picks for Lawnparties! e. Thank you to Laura, Jonah, and Ben for working on the next election! f. Thank you to Rachel for missing her friend’s wedding to be here today! 3. We will be having a shoutout form on our weekly internal e-mail. We’ll be starting that after spring break. 4. Week in Review a. Monday: Grace Lee and Dean Zeltner met regarding USG Office Renovations. i. Point Person: Grace Lee (Communications Committee) b. Tuesday: Meeting with Office Manager- internal WASS calendar for Office Managers to print and post on the list. The old bulletin board was taken down; Sarah Schneider will be the project manager. We will use this to highlight student events and student profiles. Tori and Rachel also met with Nic Chae about videos. We will have bi-weekly videos with updates, buzzfeed videos, and a serious video series with failure and loneliness. We will also be making a video on room draw; Kevin, Elizabeth and Ruby will be taking point on that. c. Wednesday: Met with Alumni Affairs Chair, Dora. We will have a Reunions Wine and Cheese event on Friday, June 1st at 4:00 PM.