Improvement of Commercial Maize Production For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

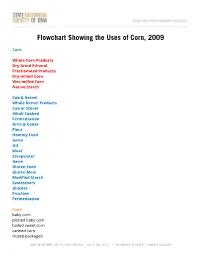

Transcript of Flowchart Showing the Uses of Corn

Flowchart Showing the Uses of Corn, 2009 Corn Whole Corn Products Dry Grind Ethanol Fractionated Products Dry-milled Corn Wet-milled Corn Native Starch Cob & Kernel Whole Kernel Products Cob or Stover Alkali Cooked Fermentation Grits & Cones Flour Hominy Feed Germ Oil Meal Steepwater Germ Gluten Feed Gluten Meal Modified Starch Sweeteners Glucose Fructose Fermentation Food baby corn pickled baby corn boiled sweet corn canned corn frozen packaged IOWA DEPARTMENT OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS 600 E. LOCUST ST. DES MOINES, IA 50319 IOWACULTURE.GOV Industrial Decorative items (pod & Indian corn) Food popcorn snack food corn nuts posole canned corn soup mixes canned hominy frozen packaged Feed livestock feed wild animal feed Industrial polishing media furfural (chemical feedstock) liquid spill recovery media dust adsorbent construction board cosmetic powders Food tortilla flours hominy corn chips tortilla chips taco shells sopapillas atoles posole menudo tostados Industrial & Fuel fuel ethanol distillers dried grains with solubles oil for biodiesel Food breakfast cereals fortified foods pinole snack foods maize porridges alkali cooked products breads & bakery products fermented beverages unfermented beverages pet foods corn bread Industrial wallpaper paste floor wax hand soap dusting agents Food bakery products masa flour snack foods baby foods baking mixes batters desserts pie fillings gravies & sauces salad dressings frozen foods meat extenders non-meat extenders thickening agents Industrial fermentation media explosives gypsum wallboard paper -

Corn Has Diverse Uses and Can Be Transformed Into Varied Products

Maize Based Products Compiled and Edited by Dr Shruti Sethi, Principal Scientist & Dr. S. K. Jha, Principal Scientist & Professor Division of Food Science and Postharvest Technology ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa New Delhi 110012 Maize is also known as Corn or Makka in Hindi. It is one of the most versatile crops having adaptability under varied agro-climatic conditions. Globally, it is known as queen of cereals due to its highest genetic yield potential among the cereals. In India, Maize is grown throughout the year. It is predominantly a kharif crop with 85 per cent of the area under cultivation in the season. The United States of America (USA) is the largest producer of maize contributing about 36% of the total production. Production of maize ranks third in the country after rice and wheat. About 26 million tonnes corn was produced in 2016-17 from 9.6 Mha area. The country exported 3,70,066.11 MT of maize to the world for the worth of Rs. 1,019.29 crores/ 142.76 USD Millions in 2019-20. Major export destinations included Nepal, Bangladesh Pr, Myanmar, Pakistan Ir, Bhutan The corn kernel has highest energy density (365 kcal/100 g) among the cereals and also contains vitamins namely, vitamin B1 (thiamine), B2 (niacin), B3 (riboflavin), B5 (pantothenic acid) and B6. Although maize kernels contain many macro and micronutrients necessary for human metabolic needs, normal corn is inherently deficient in two essential amino acids, viz lysine and tryptophan. Maize is staple food for human being and quality feed for animals. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista de Administração de Empresas ISSN: 0034-7590 ISSN: 2178-938X Fundação Getulio Vargas, Escola de Administração de Empresas de S.Paulo DÓRIA, CARLOS ALBERTO OF POROTOS AND BEANS Revista de Administração de Empresas, vol. 58, no. 3, 2018, May-June, pp. 325-331 Fundação Getulio Vargas, Escola de Administração de Empresas de S.Paulo DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020180314 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=155158452012 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative RAE-Revista de Administração de Empresas | FGV EAESP ESSAYS Invited article Original version DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-759020180314 OF POROTOS AND BEANS Academic studies have tried to bring to light the process of establishing a national narrative on cuisine, focusing mainly on how the clash between the upper class and the popular cuisine is presently affected throughout the construction of a new perception of history(Bornand, 2012). In general terms, even more homogeneously than it may seem at first glance, there is a prevail- ing thesis on the formation of Latin-American national cuisines which claims that these are mis- cegenated entities. It claims, in Brazil’s case, that indigenous and African recipes have been as- similated and improved through the adoption of European techniques, creating the national cuisine. Even in the case of excolonies, the highlight is given invariably to the dominance of adop- tion processes of European techniques, as in a global adaptation of western cuisine itself. -

Advancedaudioblogs3#1 Peruviancuisine:Lacomida Peruana

LESSON NOTES Advanced Audio Blog S3 #1 Peruvian Cuisine: La Comida Peruana CONTENTS 2 Dialogue - Spanish 4 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 5 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2020 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. DIALOGUE - SPANISH MAIN 1. Hola a todos! 2. Alguno ya tuvo la oportunidad de degustar algún plato típico peruano? 3. La comida peruana es una de las cocinas más diversas del mundo, incluso han llegado a decir que la cocina peruana compite con cocinas de alto nivel como la francesa y china. 4. La comida peruana es de gran diversidad gracias al aporte de diversas culturas como la española, italiana, francesa, china, japonesa, entre otras, originando de esta manera una fusión exquisita de distintos ingredientes y sabores que dieron lugar a distintos platos de comida peruana. 5. A este aporte multicultural a la cocina peruana, se suman la diversidad geográfica del país (el Perú posee 84 de las 104 zonas climáticas de la tierra) permitiendo el cultivo de gran variedad de frutas y verduras durante todo el año. 6. Asimismo el Perú tiene la bendición de limitar con el Océano Pacífico, permitiendo a los peruanos el consumo de diversos platos basados en pescados y mariscos. 7. La comida peruana ha venido obteniendo un reconocimiento internacional principalmente a partir de los años 90 gracias al trabajo de muchos chefs que se encargaron de difundir la comida peruana en el mundo y desde entonces cada vez más gente se rinde ante la exquisita cocina peruana. 8. En el año 2006, Lima, la capital del Perú, fue declarada capital gastronómica de América durante la Cuarta Cumbre Internacional de Gastronomía Madrid Fusión 2006. -

Anthocyanins Content in the Kernel and Corncob of Mexican Purple Corn Populations

MaydicaOriginal paper Open Access Anthocyanins content in the kernel and corncob of Mexican purple corn populations 1 1 2 Carmen Gabriela Mendoza-Mendoza , Ma. del Carmen Mendoza-Castillo *, Adriana Delgado-Alvarado , Francisco Javier Sánchez-Ramírez3,Takeo Ángel Kato-Yamakake1 1 Postgrado en Recursos Genéticos y Productividad-Genética, Campus Montecillo, Colegio de Postgraduados, Km 36.5 Carretera México- Texcoco. 56230, Montecillo, Texcoco, estado de México, México. 2 Campus Puebla, Colegio de Postgraduados. Boulevard Forjadores de Puebla No. 205.72760. Santiago Momoxpan, Municipio San Pedro Cholula, Puebla, México. 3 Departamento de Fitomejoramiento, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro. Calzada Antonio Narro 1923, Buenavista, Saltillo, 25315. Coahuila, México. * Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Zea mays L., purple corn,anthocyanins, native corn, and San Juan Ixtenco, Tlaxcala. Abstract Purple corn has acquired great interest by its high content of anthocyanins and bioactive properties. Among this type of corn the Andean purple corn has been the most studied, however, in Mexico, we have the “maíces mora- dos”, which is recognized by its dark purple color. Since there is no record about its content of anthocyanins, in this study we quantified the total anthocyanins (TA) accumulated in the pericarp, aleurone layer, kernel, and corn- cob of 52 corn populations with different grades of pigmentation. Results showed that TA was superior in purple corn than in blue and red corn. TA ranged from 0.0044 to 0.0523 g of TA ∙ 100 g-1 of biomass in the aleurone layer; in the pericarp from 0.2529 to 2.6452 g of TA ∙ 100 g-1 of pericarp; in the kernel from 0.0398 to 0.2398 g of TA ∙ 100 g-1 of kernel and in the corncob from 0.1004 to 1.1022 g of TA ∙ 100 g-1 of corncob. -

Purple Corn (Zea Mays L.)

Purple Corn (Zea mays L.) Purple corn was once a sacred crop to the ancient Incan PURPLE CORN BENEFITS civilizations. Now hundreds of years later, it is grown commercially • One of the most potent vegetable sources of the in its native land of Peru. Historically it was valued for its use as antioxidant-rich color pigments called anthocyanins a natural colorant for foods and beverages as well as for its role in • Supports healthy glucose and lipid metabolism making a popular drink called “chicha morada.” Today’s markets • Powerful antioxidant activity still acknowledge the more traditional uses while research into the • Promotes healthy aging and vascular integrity health benefits of this particular type of corn have made it a sought- after ingredient in the functional foods and supplements markets as PHYTONUTRIENT PROFILE well. Researchers have discovered the significant role of purple corn Contains one of the highest concentrations of and its effects on cellular health, obesity, diabetes, inflammation and • cyanidin-3-glucoside compared to other anthocyanin- vascular integrity. These health benefits are largely tied to purple rich fruits and vegetables corn’s high content of anthocyanins, the antioxidant-rich color • Unique and diverse anthocyanin profile containing pigments that give it its dark purple color. In fact, purple corn has predominantly cyanidins, pelargonidins, and one of the absolute highest levels of a particular anthocyanin— peonidins cyanidin-3-glucoside—that has been attributed to a number of • Rich in phenolic acids such as p-coumaric, vanillic acid, protocatechuric acid, and flavonoids such as significant health benefits in humans. Fun Fact: Offerings of purple quercetin corn were given to honor athletes just prior to their sacrifice to Incan gods. -

Factors Influencing Commercialization of Green Maize in Nandi South, Nandi County Kenya by Pius Kipkorir Cheruiyot a Thesis Subm

FACTORS INFLUENCING COMMERCIALIZATION OF GREEN MAIZE IN NANDI SOUTH, NANDI COUNTY KENYA BY PIUS KIPKORIR CHERUIYOT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION FOR THE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION AND POLICY MOI UNIVERSITY DECEMBER, 2018 ii DECLARATION Declaration by the Student I declare that this thesis is my original work and has not been presented for the award of degree in any another university. No part of this thesis may be reproduced without prior written permission of the Author and/ or Moi University Pius Kipkorir Cheruiyot ……………………… ……………… SASS/PGPA/06/07 Signature Date Declaration By the Supervisors This thesis has been submitted for examination with our Approval as University Supervisors. Dr. James K. Chelang’a ……………………… ……………… Department of History, Political Signature Date Science and Public Administration Mr. Dulo Nyaoro ……………………… ……………… Department of History, Political Signature Date Science and Public Administration iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my beloved wife Mercy Cheruiyot, children Kipkoech, Kimaru, Jerop, and Jepkurui. To my parents Sosten Cheruiyot and Anjaline Cheruiyot, siblings and all my friends for their inspiration, encouragement and continuous support throughout the entire process of writing this research thesis. God Bless you all. iv ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to assess the factors that influenced the commercialization of green maize in Nandi South, Nandi County. The Study aimed at investigating the reasons why farmers opted to sell green maize rather than wait to sell it as dry cereals. The study aimed at achieving the following objectives; to analyze policies that guide the commercialization of green maize; to assess factors that motivate farmers to sell their green maize, to evaluate the consequences of the sale of green maize and to assess the positive ant the negative results of the sale of green maize. -

Grains Purple Corn Conventional

IMEX FUTURA S.A.C|C/Tulipanes 147 of 304, Centro Emp. Blu Building Urb. Polo Hunt. Surco- Lima,Perú.T 51(1)7193969 www.imexfutura.com PRODUCT SPECIFICATION - GRAINS Art.: Name: PURPLE CORN CONVENTIONAL It is grown only in Peru over 2500 years ago used in the preparation of chicha morada and mush. Phenols compounds of General description: purple corn are powerful antioxidants that protect cell membranes and DNA from the damaging effects of free radicals. Also, anthocyanins are powerful antioxidants that reduce body aging, reduce the risk of heart attack and are excellent preventive against cancer Packaging Unit: 425g/453g Units/Box: 16 u. Box/Pallet: 100 box 25Kg paper PP/PB PP/PB PP/PB bags, or other in a CLEAR in a clear bag Packaging: according BAG w/ lithographed inside of client’s need sticker on it, retail bag lithographe or d carton lithographed box Shelf life: 2 year Contact: Daniel Saint-Pere Caprile 20´ FCL with 22 MT – Eur / 20´ FCL with 20´ FCL with 220´ FCL with Shipping Layout South America 10 pallets 10 pallets 10 pallets 21.5MT– Au/ 40´ FCL with 40´ FCL with 40´ FCL with Canada 19.9 20 pallets 20 pallets 20 pallets MT – EEUU Products Certifications HACCP Facility certifications Ingredients declaration PURPLE CORN (Zea Mays L.) PURITY CHARACTERISTICS Purity (%) 99.95% Foreign seeds(%) 0.05% max. Moisture (%) 13.0% max. IMEX FUTURA S.A.C|C/Tulipanes 147 of 304, Centro Emp. Blu Building Urb. Polo Hunt. Surco- Lima,Perú.T 51(1)7193969 www.imexfutura.com IMEX FUTURA S.A.C|C/Tulipanes 147 of 304, Centro Emp. -

Post-Harvest Operations

MAIZE Post-harvest Operations - Post-harvest Compendium MAIZE: Post-Harvest Operation Organisation:Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), AGST Author: Danilo Mejía, PhD, AGST. Edited by AGST/FAO: Danilo Mejía, PhD, FAO (Technical) Last reviewed: 15/05/2003 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Economic and Social Impact. ...................................................................................... 7 1.2 World trade ................................................................................................................ 12 1.3 Maize primary products. ............................................................................................ 15 1.4 Secondary and derived products from maize ............................................................. 21 1.5 Requirements for export and quality assurance. ........................................................ 28 1.6 Consumer preferences. ............................................................................................... 30 1.7 Others. ........................................................................................................................ 32 2. Post-production Operations ......................................................................................... 38 2.1. Pre-harvest operations. .............................................................................................. 38 2.2. Harvesting ................................................................................................................ -

SNACKS PASTA LARGE PLATES from the HEARTH (A La Carte)

SNACKS PASTA OUR DAILY BREAD | $12 HEIRLOOM TOMATO AGNOLOTTI | $23 marbled butter | whipped nduja | arbequina olive oil & saba burrata | tomato water | basil TAPIOCA BRAZILIAN CHEESE FRITTER | $14 FUSILLI VERDE | $23 house made capicola | farm pickles | our smoked hot sauce pork ragu | herbs | chili | parmesan GRILLED “BEACH CHEESE” ON A STICK | $6/ea SQUID INK BUCATINI | $29 hot honey | oregano | lime santa barbara uni | malagueta pepper | marcona almonds SESAME GARLIC PANCAKE | $10/ea RICOTTA CAVATELLI CACIO E PEPE| $32 avocado | regiis ova caviar | chive quicke’s cheddar | confit peppercorns | black truffle RED CRAB TOAST| $16 grilled sourdough | sugar rush aioli | fennel pollen LARGE PLATES BEEF TARTARE | $9 ROHAN DUCK BREAST | $38 black truffle XO | crispy garlic | shiso leaf yucca mash | spring onions | goiabada HALF DOZEN OYSTERS | $19 BLUE PRAWN MOQUECA | $36 gooseberry | thai chile | rose mignonette charred plantain and coconut broth | dende oil | steamed rice SNAKE RIVER WAGYU PICANHA | $58 crispy potatoes | eggplant caponata | bordelaise SMALL PLATES ALBACORE TUNA | $36 PURSLANE & GARDEN SALAD | $12 summer squash | fairytale eggplant | bluefin tonnato | currants crunchy seeds | herb goddess | lemon vinaigrette KOHLRABI “CAESAR” | $14 fried egg aioli | mint | aged pecorino | herb breadcrumbs FROM THE HEARTH (a la carte) CURED FLUKE TARTARE | $18 HALF CHICKEN| $32 bonito cream | finger lime vinaigrette | pickled myoga piri piri | chicken jus BRAISED SQUID | $17 WHOLE OCTOPUS | $95 polenta cake | heirloom peperonata | garden fennel -

Jeffery's Catering Product Ingredients

JEFFERY’S CATERING PRODUCT INGREDIENTS CEREAL CORN FLAKES BOWL #4265708 – INGREDIENTS: MILLED CORN, SUGAR, SALT, MALT EXTRACT, CORN SYRUP, VITAMIN C (SODIUM ASCORBATE), REDUCED IRON, ZINC (ZINC OXIDE), NIACIN (NIACINAMIDE), VITAMIN A PALMITATE, VITAMIN B6 (PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN D, VITAMIN B2 (RIBOFLAVIN), VITAMIN B1 (THIAMIN MONONITRATE), FOLATE (FOLIC ACID), VITAMIN B12, WHEAT STARCH. BHT TO PRESERVE FRESHNESS. CONTAINS WHEAT SERVING SIZE: 1 BOWL CALORIES 80, TOTAL FAT 0G, CARBOHYDRATE 18G, PROTEIN 2G, SAT. FAT 0G, TRANS FAT 0G KIX WHOLE GRAIN SS BOWL # 1072586 – INGREDIENTS: WHOLE GRAIN CORN, CORN MEAL, SUGAR, CORN BRAN, SALT, BROWN SUGAR SYRUP, TRISODIUM PHOSPHATE. VITAMIN E (MIXED TOCOPHEROLS) ADDED TO PRESERVE FRESHNESS.VITAMINS AND MINERALS: CALCIUM CARBONATE, IRON AND ZINC (MINERAL NUTRIENTS), VITAMIN C (SODIUM ASCORBATE), B VITAMIN (NIACINAMIDE), VITAMIN B6 (PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN B2 (RIBOFLAVIN), VITAMIN B1 (THIAMIN MONONITRATE), VITAMIN A (PALMITATE), B VITAMIN (FOLIC ACID), VITAMIN B12, VITAMIN D3. SERVING SIZE: 1 BOWL PACK, CALORIES 60, TOTAL FAT 0.5G, CARBOHYDRATE 15G, PROTEIN 1G, SUGARS 2G, FIBER 2G RICE CRISPY BOWL # 1265701 – INGREDIENTS: RICE, SUGAR, SALT, HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, MALT EXTRACT, FERRIC ORTHOPHOSPHATE (IRON), VITAMIN C (ASCORBIC ACID), ZINC (ZINC OXIDE), NIACIN (NIACINAMIDE), VITAMIN A PALMITATE, VITAMIN B6 (PYRIDOXINE HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN B2 (RIBOFLAVIN), VITAMIN B1 (THIAMIN HYDROCHLORIDE), VITAMIN D, FOLATE (FOLIC ACID), VITAMIN B12. BHT (TO PRESERVE FRESHNESS). SERVING SIZE: 1 BOWL PACK CALORIES 70, TOTAL FAT 0G, CARBOHYDRATE 16G, PROTEIN 1G, SUGARS 2G, FIBER 0G TOASTY O’S BOWL # 7738776 – INGREDIENTS: WHOLE GRAIN OAT FLOUR (INCLUDES THE OAT BRAN), OAT BRAN, WHEAT STARCH, CONTAINS 2% OR LESS OF: SALT, TRISODIUM PHOSPHATE, CARAMEL COLOR. -

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Repository ISTITUZIONALE APPROACH OF THE SYSTEMIC DESIGN IN MATERIAL AND INTANGIBLE CULTURE OF ESTRADA REAL: Original APPROACH OF THE SYSTEMIC DESIGN IN MATERIAL AND INTANGIBLE CULTURE OF ESTRADA REAL: TERRITORIAL SERRO CASE / CARVALHAES PEGO, KATIA ANDREA. - (2016). Availability: This version is available at: 11583/2644209 since: 2016-07-08T20:41:56Z Publisher: Politecnico di Torino Published DOI:10.6092/polito/porto/2644209 Terms of use: openAccess This article is made available under terms and conditions as specified in the corresponding bibliographic description in the repository Publisher copyright (Article begins on next page) 04 August 2020 EUROPEAN PhD in PRODUCTION SYSTEMS & INDUSTRIAL DESIGN XXVIII cycle - years 2013-2015 supervisor: prof. arch. Luigi BISTAGNINO APPROACH OF THE SYSTEMIC DESIGN IN MATERIAL AND INTANGIBLE CULTURE OF ESTRADA REAL: Territorial Serro Case candidate: Kátia Andréa CARVALHAES PÊGO PhD IN MANAGEMENT, PRODUCTION AND DESIGN POLITECNICO DI TORINO UEMG - FAPEMIG Kátia Andréa CARVALHAES PÊGO APPROACH OF THE SYSTEMIC DESIGN IN MATERIAL AND INTANGIBLE CULTURE OF ESTRADA REAL: TERRITORIAL SERRO CASE Advisor: professor architect Luigi BISTAGNINO Keywords: Systemic Design; Material and Immaterial Culture; Crafts. TORINO | March | 2016 To the future. acknowledgements I thank my advisor professor Luigi Bistagnino for the wealthy experience and learning during the three years of coexistence, for his patience and efficiency in teaching, for his firmness, for all “yes” and, especially, for each “no” I heard. I thank my father for the seriousness and persistence inherited, because without these qualities I could not get to that point, and re- member that, although deceased, is still running through my veins. I thank my mother, for love, dedication and support throughout all my life, cherishing me in my every discouragement, and remem- bering me that often things are simpler than they seem.