Dissertation Final for Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leonard Slatkin at 70: the DSO's Music Director Was Born for The

Leonard Slatkin at 70: The DSO’s music director was born for the podium By Lawrence B. Johnson Some bright young musicians know early on that they want to be a conductor. Leonard Slatkin, who turned 70 Slatkin at 70: on September 1, had a more specific vision. He believed himself born to be a music director. Greatest Hits “First off, it was pretty clear that I would go into conducting once I had the opportunity to actually lead an orchestra,” says Slatkin, music director of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra since 2008 and occupant of the same post with the Orchestre National de Lyon since 2011. “The study process suited my own ethic and, at least for me, I felt relatively comfortable with the technical part of the job.” “But perhaps more important, I knew that I would also be a music director. Mind you, this is a very different job from just getting on the podium and waving your arms. The decision making process and the ability to shape a single ensemble into a cohesive whole, including administration, somehow felt natural to me.” Slatkin arrived at the DSO with two directorships already under his belt – the Saint Louis Symphony (1979-96) and the National Symphony in Washington, D.C. (1996-2008) – and an earful of caution about the economically distressed city and the hard-pressed orchestra to which he was being lured. But it was a challenge that excited him. “Almost everyone warned me about the impending demise of the orchestra,” the conductor says. “A lot of people said that I should not take it. -

Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia

Title Artist Label Tchaikovsky: Pathetique Symphony New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 6689 Prokofiev: Two Sonatas for Violin and Piano Wilkomirska and Schein Connoiseur CS 2016 Acadie and Flood by Oliver and Allbritton Monroe Symphony/Worthington United Sound 6290 Everything You Always Wanted to Hear on the Moog Kazdin and Shepard Columbia M 30383 Avant Garde Piano various Candide CE 31015 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 352 Dance Music of the Renaissance and Baroque various MHS OR 353 Claude Debussy Melodies Gerard Souzay/Dalton Baldwin EMI C 065 12049 Honegger: Le Roi David (2 records) various Vanguard VSD 2117/18 Beginnings: A Praise Concert by Buryl Red & Ragan Courtney various Triangle TR 107 Ravel: Quartet in F Major/ Debussy: Quartet in G minor Budapest String Quartet Columbia MS 6015 Jazz Guitar Bach Andre Benichou Nonsuch H 71069 Mozart: Four Sonatas for Piano and Violin George Szell/Rafael Druian Columbia MS 7064 MOZART: Symphony #34 / SCHUBERT: Symphony #3 Berlin Philharmonic/Markevitch Dacca DL 9810 Mozart's Greatest Hits various Columbia MS 7507 Mozart: The 2 Cassations Collegium Musicum, Zurich Turnabout TV-S 34373 Mozart: The Four Horn Concertos Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Mason Jones Columbia MS 6785 Footlifters - A Century of American Marches Gunther Schuller Columbia M 33513 William Schuman Symphony No. 3 / Symphony for Strings New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia MS 7442 Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor Westminster Choir/various artists Columbia ML 5200 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 (Pathetique) Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Columbia ML 4544 Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 5 Cleveland Orchestra/Rodzinski Columbia ML 4052 Haydn: Symphony No 104 / Mendelssohn: Symphony No 4 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Columbia ML 5349 Porgy and Bess Symphonic Picture / Spirituals Minneapolis Symphony/Dorati Mercury MG 50016 Beethoven: Symphony No 4 and Symphony No. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

2017 20Th/21St-Century Piano Festival

Piano Area presents 2017 th st 20 / 21 - Century Piano Festival Dr. Sookkyung Cho, Director Dr. Helen Marlais, Founding Director Saturday, October 28, 2017 Sherman Van Solkema Recital Hall Haas Center for Performing Arts Composer-in-Residence For 25 years Bill Ryan has been a tireless advocate of contemporary music. Through his work as a composer, conductor, producer and educator, he has engaged audiences throughout the country with the music of our time. He has won the American Composers Forum Champion of New Music Award, the Michigan Governor’s Award in Arts Education, and the Distinguished Contribution to a Discipline Award at Grand Valley State University. As a concert producer, Bill has presented over 65 events in his Open Ears and Free Play concert series, gaining national recognition with three ASCAP/Chamber Music America Adventurous Programming Awards. Notable guests have included eighth blackbird, Prism, So Percussion, Ethel, Lisa Moore, Todd Reynolds, Julia Wolfe, Talujon, Michael Lowenstern, and the Michael Gordon Band. -

James M. Black and Friends, Contributions of Williamsport PA to American Gospel Music

James M. Black and Friends Contributions of Williamsport PA to American Gospel Music by Milton W. Loyer, 2004 Three distinctives separate Wesleyan Methodism from other religious denominations and movements: (1) emphasis on the heart-warming salvation experience and the call to personal piety, (2) concern for social justice and persons of all stations of life, and (3) using hymns to bring the gospel message to people in a meaningful way. All three of these distinctives came together around 1900 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, in the person of James M. Black and the congregation at the Pine Street Methodist Episcopal Church. Because there were other local persons and companies associated with bands, instruments and secular music during this time, the period is often referred to as “Williamsport’s Golden Age of Music.” While papers have been written on other aspects of this musical phenomenon, its evangelical religious component has generally been ignored. We seek to correct that oversight. James Milton Black (1856-1938) is widely known as the author of the words and music to the popular gospel song When the Roll is Called Up Yonder . He was, however, a very private person whose failure to leave much documentation about his work has frustrated musicologists for decades. No photograph of him suitable for large-size reproduction in gospel song histories, for example, is known to exist. Every year the United Methodist Archives at Lycoming College expects to get at least one inquiry that begins, “I just discovered that James M. Black was a Methodist layperson from Williamsport, could you please tell me…” We now attempt to bring together all that is known about the elusive James M. -

Download Booklet

559216-18 bk Bolcom US 12/08/2004 12:36pm Page 40 AMERICAN CLASSICS WILLIAM BOLCOM Below: Longtime friends, composer William Bolcom and conductor Leonard Slatkin, acknowledge the Songs of Innocence audience at the close of the performance. and of Experience (William Blake) Soloists • Choirs University of Michigan Above: Close to 450 performers on stage at Hill Auditorium in Ann Arbor, Michigan, under the School of Music baton of Leonard Slatkin in William Bolcom’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Symphony Orchestra University Musical Society All photographs on pages 37-40 courtesy of Peter Smith/University Musical Society Leonard Slatkin 8.559216-18 40 559216-18 bk Bolcom US 12/08/2004 12:36pm Page 2 Christine Brewer • Measha Brueggergosman • Ilana Davidson • Linda Hohenfeld • Carmen Pelton, Sopranos Joan Morris, Mezzo-soprano • Marietta Simpson, Contralto Thomas Young, Tenor • Nmon Ford, Baritone • Nathan Lee Graham, Speaker/Vocals Tommy Morgan, Harmonica • Peter “Madcat” Ruth, Harmonica and Vocals • Jeremy Kittel, Fiddle The University Musical Society The University of Michigan School of Music Ann Arbor, Michigan University Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Kiesler, Music Director Contemporary Directions Ensemble/Jonathan Shames, Music Director University Musical Society Choral Union and University of Michigan Chamber Choir/Jerry Blackstone, Conductor University of Michigan University Choir/Christopher Kiver, Conductor University of Michigan Orpheus Singers/Carole Ott, William Hammer, Jason Harris, Conductors Michigan State University Children’s Choir/Mary Alice Stollak, Music Director Leonard Slatkin Special thanks to Randall and Mary Pittman for their continued and generous support of the University Musical Society, both personally and through Forest Health Services. Grateful thanks to Professor Michael Daugherty for the initiation of this project and his inestimable help in its realization. -

New Music Festival March 26Th – March 28Th, 2018 Co-Directors

Illinois State University RED NOTE new music festival March 26th – March 28th, 2018 co-directors , distinguished guest composer , distinguished guest composer , guest performers CALENDAR OF EVENTS MONDAY, MARCH 26TH 8 pm, Center for the Performing Arts The Festival opens with a concert featuring the Illinois State University Wind Symphony and Illinois State University choruses. Professor Anthony Marinello conducts the ISU Wind Symphony in a performance of the winning work in this year’s Composition Competition for Wind Ensemble, Patrick Lenz’s Pillar of Fire. The Wind Symphony also performs guest composer William Bolcom’s Concerto for Soprano Saxophone with ISU faculty Paul Nolen, and the world premiere of faculty composer Martha Horst’s work Who Has Seen the Wind? The ISU Concert Choir and Madrigal Singers, conducted by Dr. Karyl Carlson, perform the winning piece in the Composition Competition for Chorus, Wind on the Island by Michael D’Ambrosio, as well as William Bolcom’s Song for Saint Cecilia’s Day. TUESDAY, MARCH 27TH 7:30 pm, Kemp Recital Hall ISU students and faculty present a program of works by featured guest composers Gabriela Lena Frank and William Bolcom. The concert will also include the winning work in this year’s Composition Competition for Chamber Ensemble, Downloads, by Jack Frerer. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 28TH 7:30 pm, Kemp Recital Hall Ensemble Dal Niente takes the stage to perform music of contemporary European composers, including Salvatore Sciarrino, Kaija Saariaho, and György Kurtag. THURSDAY, MARCH 29TH 7:30 pm, Kemp Recital Hall The Festival concludes with a concert of premieres by the participants in the RED NOTE New Music Festival Composition Workshop: James Chu, Joshua Hey, Howie Kenty, Joungmin Lee, Minzuo Lu, Mert Morali, Erik Ransom, and Mac Vinetz. -

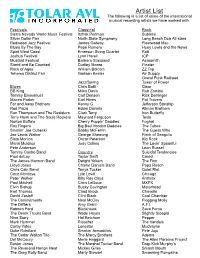

Artist List the Following Is a List of Some of the International Musical Recording Artists We Have Worked With

Artist List The following is a list of some of the international musical recording artists we have worked with. Festivals Classical Rock Sierra Nevada World Music Festival Itzhak Perlman Sublime Silver Dollar Fair North State Symphony Long Beach Dub All-stars Redwood Jazz Festival James Galway Fleetwood Mac Blues By The Bay Pepe Romero Huey Lewis and the News Spirit West Coast Emerson String Quartet Ratt Joshua Festival Lynn Harell ICP Mustard Festival Barbara Streisand Aerosmith Stand and Be Counted Dudley Moore Floater Rock of Ages William Bolcom ZZ Top Tehema District Fair Garison Keeler Air Supply Grand Funk Railroad Jazz/Swing Tower of Power Blues Chris Botti Gwar BB King Miles Davis Rob Zombie Tommy Emmanuel Carl Denson Rick Derringer Maceo Parker Earl Hines Pat Travers Far and Away Brothers Kenny G Jefferson Starship Rod Piaza Eddie Daniels Allman Brothers Ron Thompson and The Resistors Clark Terry Iron Butterfly Terry Hank and The Souls Rockers Maynard Ferguson Tesla Norton Buffalo Cherry Poppin’ Daddies Foghat Roy Rogers Big Bad Voodoo Daddies The Tubes Smokin’ Joe Cubecki Bobby McFerrin The Guess Who Joe Lewis Walker George Shearing Flock of Seagulls Sista Monica Oscar Peterson Kid Rock Maria Muldaur Judy Collins The Lovin’ Spoonful Pete Anderson Leon Russel Tommy Castro Band Country Suicidal Tendencies Paul deLay Taylor Swift Creed The James Harmon Band Dwight Yokem The Fixx Lloyd Jones Charlie Daniels Band Papa Roach Chris Cain Band Tanya Tucker Quiet Riot Coco Montoya Lyle Lovitt Chicago Peter Welker Billy Ray Cirus Anthrax Paul Mitchell Chris LeDoux MXPX Elvin Bishop Bucky Covington Motorhead Earl Thomas Chad Brock Chavelle David Zasloff Clint Black Coal Chamber The Commitments Neal McCoy Flogging Molly The Drifters Amy Grant A.F.I. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Williams College Department of Music

Williams College Department of Music Visiting Artist Joel Fan, piano Richard Wagner Prelude from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (1813 – 1883) Johannes Brahms Sechs Klavierstücke op. 118 (1833 – 1897) No. 1. Intermezzo in A Minor. Allegro non assai, ma molto appassionato No. 2. Intermezzo in A Major. Andante teneramente No. 3. Ballade in G Minor. Allegro energico No. 4. Intermezzo in F Minor. Allegretto un poco agitato No. 5. Romanze in F Major. Andante No. 6. Intermezzo in E flat Minor. Andante, largo e mesto Franz Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 (1811 – 1886) ***Intermission*** Ernesto Nazareth Vem ca Branquinha (1863 – 1934) Heitor Villa-Lobos Alma Brasileira (1887 – 1959) Dia Succari La Nuit du Destin (b. 1938) George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue (1898 – 1937) Friday, February 28, 2014 8:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts Please turn off cell phones. No photography or recording is permitted. Joel Fan From recitals at Ravinia Festival in Chicago, Jordan Hall in Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in NYC and The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., to the University of Calgary Celebrity Series, and performances with the chamber orchestra, A Far Cry, performing Mozart at the Gardner Museum in Boston, the Newman Center in Denver and the Vilar Center in Beaver Creek, Colorado, Joel has found an enthusiastic following that landed his first CD at No. 3 on the Billboard Classical Chart. Joel's past appearances also include performances with Yo-Yo Ma with the New York Philharmonic, The Boston Symphony Orchestra, as well as performances with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, The New Hampshire Festival Orchestra, and the Singapore Philharmonic. -

American Composers Orchestra Presents Next Composer to Composer Talks in January

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Christina Jensen, Jensen Artists 646.536.7864 x1 [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Presents Next Composer to Composer Talks in January William Bolcom & Gabriela Lena Frank Wednesday, January 13, 2021 at 5pm ET – Online Registration & Information: http://bit.ly/ComposerToComposerBolcom John Corigliano & Mason Bates Wednesday, January 27, 2021 at 5pm ET – Online Registration & Information: http://bit.ly/ComposerToComposerCorigliano Free, registration recommended. New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) presents its next Composer to Composer Talks online in January, with composers William Bolcom and Gabriela Lena Frank on Wednesday, January 13, 2021 at 5pm ET, and John Corigliano and Mason Bates on Wednesday, January 27, 2021 at 5pm ET. The talks will be live-streamed and available for on-demand viewing for seven days. Tickets are free; registration is highly encouraged. Registrants will receive links to recordings of featured works in advance of the event. ACO’s Composer to Composer series features major American composers in conversation with each other about their work and leading a creative life. The intergenerational discussions begin by exploring a single orchestral piece, with one composer interviewing the other. Attendees will gain insight into the work’s genesis, sound, influence on the American orchestral canon, and will be invited to ask questions of the artists. On January 13, Gabriela Lena Frank talks with William Bolcom about his Symphony No. 9, from 2012, of which Bolcom writes, “Today our greatest enemy is our inability to listen to each other, which seems to worsen with time. All we hear now is shouting, and nobody is listening because the din is so great.