Where Have All the Records Gone, Or When Will We Ever Learn?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comments of Helienne Lindvall, David Lowery, Blake Morgan

Electronically Filed Docket: 21-CRB-0001-PR (2023-2027) Filing Date: 07/26/2021 01:05:42 PM EDT BEFORE THE UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES COPYRIGHT ROYALTY BOARD LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In re Determination of Rates and Terms for Making and Docket No. 21–CRB–0001–PR Distributing PHonorecords (PHonorecords IV) (2023–2027) 37 CFR Part 385 Proposed Regulations COMMENTS OF HELIENNE LINDVALL, DAVID LOWERY AND BLAKE MORGAN Helienne Lindvall, David Lowery and Blake Morgan submit these comments responding to the Copyright Royalty Judges’ notice soliciting comments on whether the Judges should adopt the regulations proposed by the National Music PublisHers Association, NasHville Songwriters Association International, Sony Music Entertainment, UMG Recordings, Inc. and Warner Music Group Corp. as the so-called “Subpart B” statutory rates and terms relating to the making and distribution of pHysical or digital pHonorecords of nondramatic musical works that, if adopted by the Judges, would apply to every songwriter in the world wHose works are exploited under the U.S. compulsory mecHanical license (86 FR 33601).1 We object to the proposed rates and terms for the following reasons and respectfully suggest constructive alternatives. THe gravamen of our objection is that (1) the Subpart B rates 1 We focus in this comment almost entirely on the Subpart B rates applicable to physical carriers under 37 C.F.R. §385.11(a). We note, however, that there is some apprehension among songwriters that the “music bundle” rate in 37 C.F.R. § 385.11(c) could be twisted in a way to drag Non-Fungible Tokens into the frozen rates. -

Sammy Strain Story, Part 4: Little Anthony & the Imperials

The Sammy Strain Story Part 4 Little Anthony & the Imperials by Charlie Horner with contributions from Pamela Horner Sammy Strain’s remarkable lifework in music spanned almost 49 years. What started out as street corner singing with some friends in Brooklyn turned into a lifelong career as a professional entertainer. Now retired, Sammy recently reflected on his life accomplishments. “I’ve been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame twice (2005 with the O’Jays and 2009 with Little (Photo from the Classic Urban Harmony Archives) Anthony & the Imperials), the Vocal Group Hall of Fame (with both groups), the Pioneer R&B Hall of Fame (with Little An- today. The next day we went back to Ernie Martinelli and said thony & the Imperials) and the NAACP Hall of Fame (with the we were back together. Our first gig was to be a week-long O’Jays). Not a day goes by when I don’t hear one of the songs engagement at the Town Hill Supper Club, a place that I had I recorded on the radio. I’ve been very, very, very blessed.” once played with the Fantastics. We had two weeks before we Over the past year, we’ve documented Sammy opened. From the time we did that show at Town Hill, the Strain’s career with a series of articles on the Chips (Echoes of group never stopped working. “ the Past #101), the Fantastics (Echoes of the Past #102) and The Town Hall Supper Club was a well known venue the Imperials without Little Anthony (Echoes of the Past at Bedford Avenue and the Eastern Parkway in the Crown #103). -

PLANNER PROJECT 2016... the 60S!

1 PLANNER PROJECT 2016... THE 60s! EDITOR’S NOTE: Listed below are the venues, performers, media, events, and specialty items including automobiles (when possible), highlighting 1961 and 1966 in Planner Project 2016! 1961! 1961 / FEATURED AREA MUSICAL VENUES FROM 1961 / (17) AREA JAZZ / BLUES VENUES / (4) Kornman’s Front Room / Leo’s Casino (4817 Central Ave.) / Theatrical Restaurant / Albert Anthony’s Welcome Inn AREA POP CULTURE VENUES / (13) Herman Pirchner’s Alpine Village / Aragon Ballroom / Cleveland Arena / the Copa (1710 Euclid) / Euclid Beach (hosts Coca-Cola Day) / Four Provinces Ballroom (free records for all attendees) / Hickory Grill / Homestead Ballroom / Keith’s 105th / Music Hall / Sachsenheim Ballroom / Severance Hall / Yorktown Lanes (Teen Age Rock ‘n Bowl’ night) 1961 / FEATURED ARTISTS / MUSICAL GRPS. PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (36) / Grps.: (19)] [(-) NO. OF TIMES LISTED] FEATURED JAZZ / BLUES ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / (12) Gene Ammons / Art Blakely & the Jazz Messengers / John Coltrane / Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison / Ramsey Lewis / Jimmy McPartland / Shirley Scott / Jimmy Smith / Sonny Stitt / Stanley Turrentine / Joe Williams / Teddy Wilson POP CULTURE: FEATURED NORTHEAST OHIO / REGIONAL ARTISTS FROM 1961 / (6) Andrea Carroll / Ellie Frankel trio / Bobby Hanson’s Band / Dennis Warnock’s Combo / West Side Bandstand (with Jack Scott, Tom King & the Starfires) FEATURED NATIONAL ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (16) / Groups: (14)] Tony Bennett / Jerry Butler / Cab Calloway (with All-Star -

An Analysis of Methods of Promoting Country Music Records

397 AN ANALYSIS OF METHODS OF PROMOTING COUNTRY MUSIC RECORDS IN THE ATLANTA, GEORGIA AREA THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Betty Cruikshank Fogel, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1986 T1 I' t C M te,. ,. ~i t1 "1t N 1i N I1 O - H k-' AWkW4 I!' 1 1 an 0 5 s Z 4L I ii 18T TI-I IL p I ft F-I tr rcr ' r ii #.n , , F TIT- r : + 4 Y C I Si I i . M M FII t ! S I j Ii i3 OWN I MWAM i '*! A i SM I p -o 4r # 11 c~i I itJim f Jp a L l J..4..J...4-4.-.J' I 12111 111111 1 [1 L i i i I FF FFI . - 00-0 I - LL-L I.J. I Is to LS 'IF 11 nF-I I I f- H-H- 11 P1 +F . t-ii: ar -w-- . -.-N-+ ~i1~Ei LI 1 ktfl-.LLILI. Ld 40 looovo.") J a w11r1rr wr - - i' rer.+r BEGINNING J~aOx - ~-- ~ - ATL ANT-A L----COLU- ,.WPLO WDEN MACON TSAY. WDE B'HAM. WZK B'HAM. -- WBAM MONT. -- WLWT-FM. MONT. WKSJ MOBILE WCBXEDEN WFAI FAYETT,. WC ASH.N.C WPCM BURL.N.C. WBB _EDEN CBL-COL- WESC GREEN. WDOD CHATTi. WDXB CHATT. WIYK KNOX. WDA NASH. WSM NASH . IX-FM- NASH. -- -- WDXE LAW.TN. WCMS N. VA. WLSC RON.VA. LIB FIB BR ISTOL SOC CHARLOTTE FLORIDA WIRK--FM W. -

Where the Action Is! Where the Action Is!

[Mobile book] Where the Action Is! Where the Action Is! 7w1QS7lKf Where the Action Is! 4HGxX5Eyc RQ-22623 vyNwSLE38 USmix/Data/US-2011 c3MPWuhiE 3.5/5 From 410 Reviews wIMbx6iD5 Freddy Cannon, Mark Bego YUQLiAYoY audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC sllPRDBVx 71kU0tNRF bCAPvWIix vTSv01BK1 lBtHCN8Hr hXpqOqfCm rT7UQR046 BothGzo4X 7 of 7 people found the following review helpful. Freddy Cannon is WHERE BfoDVCyPC THE ACTION IS!By CatI loved this book! It was fun to follow Freddy on his XoBUJIxEm rise from obscurity to major rock roll star. Along the way, we are introduced to rQqTQbbWV numerous other superstars from the 50's, 60's, 70's 80's. I don't want to give lBzEIpopO anything away, but the Elvis appearances are priceless! An interesting and bwUjulCnV exciting read.4 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Where The 1QAc3p7bY Action Is ! Freddy " Boom Boom " CannonBy Frank A. Buongervino Jr.Freddy AtC3SuvvS " Boom Boom " Cannon was still is a great Rock Roller.He resents being r8R5DrWh2 lumped in with the other Teenage Idols.He thinks he's better than that. I agree 10h52PFlj with him.In reading this book I found him not to be100 % truthful.April 17, VLINcqWAB 1960 = Eddie Cochran died in a limo crash, while on tour in England.Freddy 8QeBxyuKI says he was there. My research finds this not to be true.Freddy holds the title 8cA1NF2Kf for most appearances on American Bandstand.I think this is true. I think the JUJZRCu4B number he uses is inflated.You'll enjoy this book. Don't believe everything that Hzi6QxKpn Freddy says.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. -

The History of Rock Music: 1955-1966

The History of Rock Music: 1955-1966 Genres and musicians of the beginnings History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page Inquire about purchasing the book (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) The Flood 1964-1965 (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The Tunesmiths TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The Beach Boys' idea of wedding the rhythm of rock'n'roll and the melodies of pop music was taken to its logical conclusion in Britain by the bands of the so- called "Mersey Sound". The most famous of them, the Beatles, became the object of the second great swindle of rock'n'roll. In 1963 "Beatlemania" hit Britain, and in 1964 it spread through the USA. They became even more famous than Presley, and sold records in quantities that had never been dreamed of before them. Presley had proven that there was a market for rock'n'roll in the USA. Countless imitators proved that a similar market also existed in Europe, but they had to twist and reshape the sound and the lyrics. Britain had a tradition of importing forgotten bluesmen from the USA, and became the center of the European recording industry. European rock'n'roll was less interested in innuendos, more interested in dancing, and obliged to merge with the strong pop tradition. -

A Piece of History

A Piece of History Theirs is one of the most distinctive and recognizable sounds in the music industry. The four-part harmonies and upbeat songs of The Oak Ridge Boys have spawned dozens of Country hits and a Number One Pop smash, earned them Grammy, Dove, CMA, and ACM awards and garnered a host of other industry and fan accolades. Every time they step before an audience, the Oaks bring four decades of charted singles, and 50 years of tradition, to a stage show widely acknowledged as among the most exciting anywhere. And each remains as enthusiastic about the process as they have ever been. “When I go on stage, I get the same feeling I had the first time I sang with The Oak Ridge Boys,” says lead singer Duane Allen. “This is the only job I've ever wanted to have.” “Like everyone else in the group,” adds bass singer extraordinaire, Richard Sterban, “I was a fan of the Oaks before I became a member. I’m still a fan of the group today. Being in The Oak Ridge Boys is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.” The two, along with tenor Joe Bonsall and baritone William Lee Golden, comprise one of Country's truly legendary acts. Their string of hits includes the Country-Pop chart-topper Elvira, as well as Bobbie Sue, Dream On, Thank God For Kids, American Made, I Guess It Never Hurts To Hurt Sometimes, Fancy Free, Gonna Take A Lot Of River and many others. In 2009, they covered a White Stripes song, receiving accolades from Rock reviewers. -

President's Award

Joe Galante Think You Know Joe? President’s Award Much has been written about former Sony Music Nashville Chairman Joe Galante since he announced his decision to step down from the label group he’d been a part of for 39 years. Most recently, Galante was featured in Country Aircheck’s December issue, in which he chatted with celebrated air personality Gerry House about a wide range of topics. And his contributions to country music, Country radio, CRB and its seminar could fill more pages than are contained in this issue. So rather than tell tales of his storied success, business acumen and wide-ranging influence, this profile turns to a handful of close associates who understand Galante on a more personal level. Think you know Joe? Think again. Randy Goodman: When Joe and I came as this incredibly fiscally disciplined executive, back from New York in early 1995, we often and he is, but he took time out of his crazy day had discussions about whether there was any and my crazy day to make something happen. benefit to hiring independent promoters. Of He wasn’t going to turn a blind eye. course, in New York it was simply a matter of course to use the independents, and Joe didn’t Nancy Russell: Most people know the like it. Our attitude kind of was, “Thank God business side of Joe. There’s no doubt he’s in a we’re going back to Nashville.” very competitive business and can be a tough At some point, after we’d been back businessman. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

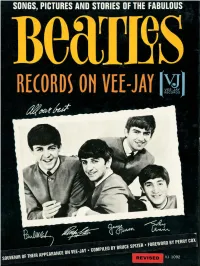

VJ-SAMPLE-CHAPTER.Pdf

i SECTION ONE—SINGLES OF SIGNIFICANCE Please, Please Me b/w Ask Me Why From Me To You b/w Thank You Girl Please, Please Me b/w From Me To You Twist And Shout b/w There’s A Place Do You Want To Know A Secret? b/w Thank You Girl Love Me Do b/w P.S. I Love You The Beatles on Oldies 45 Foreign Singles and other 7” Wonders of the World Fine Fakes of Significant Interest SECTION TWO— FINE ALBUMS OF SIGNIFICANT INTEREST Introducing The Beatles (Version One) Introducing The Beatles (Version Two) Jolly What! The Beatles & Frank Ifield on Stage Songs, Pictures and Stories of the Fabulous Beatles The Beatles vs The Four Seasons The Beatles & Frank Ifield on Stage ii Hear The Beatles Tell All The 15 Greatest Songs of The Beatles Counterfeits of Significance iii How To Use This Interactive Ebook Apps: GoodReader is the only tablet app we’ve found so far that will allow you to use all the interactive features like the GET BACK button, search, an- notate, markup and bookmarks. It has a ton of features, including syncing to drop- box. It currently costs $4.99, and it is well worth it. We have found that most other PDF readers do not handle some of the interactive features. Hopefully, as apps are Table of Contents Table updated, you will find others that work as well (let us know if you find one). Each eReader software has different ways of navigating, zooming and viewing, so please refer to your app instructions for more information. -

Sizzling 70'S Printable List

Sizzling 70’s Printable List SHE'S IN LOVE WITH YOU SUZI QUATRO BEST OF MY LOVE EAGLES WHERE YOU LEAD BARBARA STREISAND SAY YOU LOVE ME FLEETWOOD MAC SHINING STAR EARTH WIND & FIRE MIND GAMES JOHN LENNON LOVE'S THEME LOVE UNLIMITED GIRLS ON THE AVENUE RICHARD CLAPTON SOFT DELIGHTS NEW DREAM CRACKLIN' ROSIE NEIL DIAMOND AIN'T GONNA BUMP NO MORE (WITH NO BIG FAT WOMAN) JOE TEX BECAUSE I LOVE YOU MASTER'S APPRENTICES RIDE A WHITE SWAN T REX PRECIOUS LOVE BOB WELCH PRELUDE/ANGRY YOUNG MAN BILLY JOEL STAYIN' ALIVE BEE GEES EVERYBODY PLAYS THE FOOL MAIN INGREDIENT ROCK AND ROLL ALL NITE KISS NA NA HEY HEY KISS HIM GOODBYE STEAM GOODBYE STRANGER SUPERTRAMP NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE GLORIA GAYNOR GOODBYE TO LOVE CARPENTERS BABY IT'S YOU PROMISES (YOU GOTTA WALK) DON'T LOOK BACK PETER TOSH SATURDAY NIGHT BAY CITY ROLLERS SATURDAY NIGHTS ALRIGHT FOR FIGHTING ELTON JOHN ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT CAT STEVENS DANCIN' (ON A SATURDAY NIGHT) BARRY BLUE TUMBLING DICE ROLLING STONES SHAKE YOUR BOOTY K.C. & SUNSHINE BAND COZ I LUV YOU SLADE BANKS OF THE OHIO OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON FEELING ALRIGHT JOE COCKER GOOD FEELIN MAX MERRITT PEACEFUL EASY FEELING EAGLES HELLO ITS ME TODD RUNDGREN EBONY EYES BOB WELCH STAR SONG MARTY RHONE EGO (IS NOT A DIRTY WORD) SKYHOOKS ON THE COVER OF THE ROLLING STONE DR HOOK I HEAR YOU KNOCKING DAVE EDMUNDS EVERLASTING LOVE ANDY GIBB LET'S PRETEND RASPBERRIES WHO'LL STOP THE RAIN CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL BICYCLE RACE QUEEN YOU TOOK THE WORDS RIGHT OUT OF MY MOUTH (HOT SU MEAT LOAF CAPTAIN ZERO MIXTURES SWEET -

“Amarillo by Morning” the Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1

In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. On Billboard magazine’s April 4, 1964, Hot 100 2 list, the “Fab Four” held the top five positions. 28 One notch down at Number 6 was “Suspicion,” 29 by a virtually unknown singer from Amarillo, Texas, named Terry Stafford. The following week “Suspicion” – a song that sounded suspiciously like Elvis Presley using an alias – moved up to Number 3, wedged in between the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You.”3 The saga of how a Texas boy met the British Invasion head-on, achieving almost overnight success and a Top-10 hit, is one of triumph and “Amarillo By Morning” disappointment, a reminder of the vagaries The Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1 that are a fact of life when pursuing a career in Joe W. Specht music. It is also the story of Stafford’s continuing development as a gifted songwriter, a fact too often overlooked when assessing his career. Terry Stafford publicity photo circa 1964. Courtesy Joe W. Specht. In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City.