Play It Again: Rock Music Reissues and the Production of the Past for the Present Andrew J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Lessons I Learned from Working with Kiss

MARKETING LESSONS I LEARNED FROM WORKING WITH KISS BY: MICHAEL BRANDVOLD Copyright 2011 Michael Brandvold Marketing • www.MichaelBrandvold.com "Quite eloquent. You're a powerful and attractive man." Gene Simmons Copyright 2011 Michael Brandvold Marketing • www.MichaelBrandvold.com CONTENTS • About • Acknowledgements • Testimonials • No Denying the Influence • All Press is Good Press • Love Me or Hate Me, Just Spell My Name Right • Wait for the Right Time • It’s All Branding • Everything You Do Will Not Succeed • Treat the Media with Respect • Listen to Your Fans You Work for Them • The Secret to Success is to Offend the Greatest Number of People • If You Don’t Ask For It You Won’t Get It • Separate Business and Pleasure • They Aren’t Afraid to Change Their Minds • The Takeaway • Contact Copyright 2011 Michael Brandvold Marketing • www.MichaelBrandvold.com ABOUT In both mainstream and adult entertainment, Michael Brandvold’s marketing talents, skills and savvy are vital assets that numerous companies rely upon to expand, prosper and operate effectively, efficiently and profitably in the online economy. Upon graduating from Mankato State University in 1987, Michael accepted the position of Director of Marketing with DKP Productions, an artist management firm in Chicago, before joining Red Light Records 1990, as National Radio Promotions manager. A self-taught master of HTML, Michael launched websites for Perris Records, Creative Communications, Sportmart, and Montgomery Ward. But it was KISS Otaku – his KISS fan site launched in 1995 – that would change his fortunes forever. In 1998, Gene Simmons of KISS discovered KISS Otaku and personally tapped Michael as the Director of Web Services at Signatures Network, a Sony/CMGi company, where he built-from-scratch, managed and grew KISSonline into a multi-million dollar enterprise with over of a half million visitors a month. -

Download Download

Florian Heesch Voicing the Technological Body Some Musicological Reflections on Combinations of Voice and Technology in Popular Music ABSTRACT The article deals with interrelations of voice, body and technology in popular music from a musicological perspective. It is an attempt to outline a systematic approach to the history of music technology with regard to aesthetic aspects, taking the iden- tity of the singing subject as a main point of departure for a hermeneutic reading of popular song. Although the argumentation is based largely on musicological research, it is also inspired by the notion of presentness as developed by theologian and media scholar Walter Ong. The variety of the relationships between voice, body, and technology with regard to musical representations of identity, in particular gender and race, is systematized alongside the following cagories: (1) the “absence of the body,” that starts with the establishment of phonography; (2) “amplified presence,” as a signifier for uses of the microphone to enhance low sounds in certain manners; and (3) “hybridity,” including vocal identities that blend human body sounds and technological processing, where- by special focus is laid on uses of the vocoder and similar technologies. KEYWORDS recorded popular song, gender in music, hybrid identities, race in music, presence/ absence, disembodied voices BIOGRAPHY Dr. Florian Heesch is professor of popular music and gender studies at the University of Siegen, Germany. He holds a PhD in musicology from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He published several books and articles on music and Norse mythology, mu- sic and gender and on diverse aspects of heavy metal studies. -

Lt. Dan Rocks Out

HIGH DESERT WARRIOR Volume 6, Number 11 www.irwin.army.mil March 18, 2010 Published in the interest of the National Training Center and Fort Irwin community Change of Responsibility 916th Support Brigade will hold a Bri- gade Command Sergeant Major Change of Responsibility ceremony. The ceremony will take place on Monday, 4 p.m., at Jack Rabbit Park. Legal Assistance Hours Fort Irwin Legal Assistance Office hours have changed. The new schedule is as follows: Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday: 8 a.m.-4:30 p.m.; Thursday: 8 a.m.-3 p.m. Notary Services: 8 a.m.-3 p.m., Everyday, walk-in basis. Appointment calendars open: Fridays at 1 p.m. Audie Murphy Club Members of the Sgt. Audie Murphy Club will hold its monthly meeting at the SAMC Hall, located at the NTC Museum, Bldg. 587, Room 11, 12-1 p.m., March 30. For more information, contact Sgt. 1st Class Catherine Harris at 380-8386. Battle Staff Graduation Fort Irwin community is invited to at- tend the graduation ceremony of noncom- Actor Gary Sinese, performs with the Lt. Dan Band at Fort Irwin’s Army Field, March 12. The Lt. Dan Band performed a free missioned officers who will graduate from concert for the Fort Irwin community as part of his 41st USO tour. See more photos on Pages 10 and 11. Battle Staff Class 14-10 at the Post Theater, at 9 a.m., March 26. For more information, call 380-3880. Lt. Dan rocks out NTC STORY AND PHOTOS mate message to troops and their families is that was cut short because he got injured and lost Puerto Rican Birth Certificates BY SGT. -

Press 1 April 2021 the Famous Artists Behind History's Greatest Album

CNN Style The famous artists behind history's greatest album covers Leah Dolan 1 April 2021 The famous artists behind history's greatest album covers Throughout the 20th-century record sleeves regularly served as canvases for some of the world's most famous artists. From Andy Warhol's electric yellow banana on the cover of The Velvet Underground & Nico's 1967's debut album, to the custom-sprayed Banksy street art that fronted Blur's 2003 "Think Tank," art has long been used to round out the listening experience. A new book, "Art Sleeves," explores some of the most influential, groundbreaking and controversial covers from the past forty years. "This is not a 'history of album art' type book," said the book's author, DJ and arts writer DB Burkeman over email. Instead, he says the book is a "love letter" to visual art and music culture. For the 45th anniversary of "The Velvet Underground & Nico" in 2012, British artist David Shrigley illustrated a special edition reissue cover for Castle Face Records. Image: David Shrigley/Rizzoli Featured records span genres and decades. Among them are Warhol's cover for The Rolling Stones' 1971 album "Sticky Fingers," featuring the now-famous close-up of a man's crotch (often assumed, incorrectly, to be frontman Mick Jagger in tight jeans) as well as an array of seminal covers designed by graphic designer Peter Saville, co-founder of influential Manchester-based indie label Factory Records. Despite having relatively little art direction experience under his belt, Saville was behind iconic covers such as Joy Division's "Unknown Pleasures" (1979), depicting the radio waves emitted by a rotating star, and the brimming basket of wilting roses -- a muted reproduction of a 1890 painting by French artist Henri Fantin-Latour -- that fronted New Order's "Power, Corruption & Lies" (1983). -

Survey of Reissues of U.S. Recordings

Survey of Reissues of U.S. Recordings Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Recording Preservation Board, Library of Congress by Tim Brooks August 2005 Council on Library and Information Resources and Library of Congress Washington, D.C. ii The National Recording Preservation Board The National Recording Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Recording Preservation Act of 2000. Among the provisions of the law are a directive to the Board to study and report on the state of sound recording preservation in the United States. More information about the National Recording Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/rr/record/nrpb/. ISBN 1-932326-21-9 ISBN 978-1-932326-21-5 CLIR Publication No. 133 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 Web site at http://www.clir.org and Library of Congress 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $20 per copy. Orders must be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/abstract/pub133abst.html. The paper in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard 8 for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials ANSI Z39.48-1984. Copyright 2005 in compilation by the Council on Library and Information Resources and the Library of Congress. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transcribed in any form without permission of the publishers. -

THE BENNINGTON FREE PRESS Dr.Randy on the H1N1 Bvjonah LIPSKY '12 Do, Which Is Contain the Spread of Diabetes

THEBENNINGTON Financial Freeze Concerns BYCONNIE PANZARIELLO '12 etc.), Vice President for Plan which was put into effect in June, be a financially prudent option FEATURESEDITOR ning and Special Programs Joan happened at a time when it still for saving money. While Morgan Goodrich and College President didn't look like our nation was said that he wouldn't characterize ogic at our school is Liz Coleman. Morgan firmly going to be experiencing much the measure as "precautionary," a rare find. We tend denied the rumor going around economic recovery. According to it will help us save some money Lto skip some steps, that Goodrich and Coleman gave Morgan, this has an effect on our in other areas such as the always jump around, and themselves pay raises. before the donors, who are more reluctant to needed financial aid. As for elim hope things will work out for the freeze happened. Not only is this give us funds at a time of finan inating faculty positions Morgan best. Thankfully, the person who incorrect (and trust me, I asked cial crisis. said, "you never know, but I don't handles our financial matters pos the man five times, in various Also not helping the situation foresee it and it's not in our cur sesses logic in bulk, and that's ways), it is impossible: they sim is the fact that "not surprisingly rent plans." . New hires will also all that really matters, right? Bill ply do not have the power. Pay the need for financial aid has in be decided by who they are and Morgan was nice enough to clear raises have to go through the bud creased." Morgan also reiterated what position they are filling, in up the always-impressive gossip get and be approved by the Board something that we should all be tenns of salary. -

Songs of the Vietnam War Lyrics

The Limits of Power: The United States in Vietnam Name:______________________________________________ 2 Online Lesson Songs of the Vietnam War Lyrics Introduction: Throughout history, the strong feelings raised by the sacrifices, ideals, heartbreaks, and triumphs of war have often been expressed by poets and artists in songs. Songs that best cap- tured the strong feelings of Americans became very popular and lived on long after the details of the conflict were forgotten. Whether they expressed patriotism and national ideals such as inThe Star-Spangled Banner and The Battle Hymn of the Republic, sacrifice and heroism such as inWhen Johnny Comes Marching Home, or disappointment and loss such as All Quiet Along the Potomac Tonight, these songs have become part of the history. The Vietnam War was no exception. Below is a small selection of the many songs written by Americans, Vietnamese, and French about the Vietnam War. Lyndon Johnson Told the Nation By Tom Paxton (1965, folk) < http://youtu.be/JQqapCkf4Uc> I got a letter from L.B.J., it said, “This is your lucky day. It’s time to put your khaki trousers on. Though it may seem very queer, we’ve got no jobs to give you here, so we are sending you to Viet Nam” chorus And Lyndon Johnson told the nation, “Have no fear of escalation, I am trying ev’ryone to please. Though it isn’t really war, we’re sending fifty thousand more to help save Viet Nam from Viet Namese.” I jumped off the old troop ship, I sank in mud up to my hips, And cussed until the captain called me down, “never mind how hard it’s raining, Think of all the ground we’re gaining, just don’t take one step outside of town.” Every night the local gentry slip out past the sleeping sentry They go out to join the old V.C. -

Sammy Strain Story, Part 4: Little Anthony & the Imperials

The Sammy Strain Story Part 4 Little Anthony & the Imperials by Charlie Horner with contributions from Pamela Horner Sammy Strain’s remarkable lifework in music spanned almost 49 years. What started out as street corner singing with some friends in Brooklyn turned into a lifelong career as a professional entertainer. Now retired, Sammy recently reflected on his life accomplishments. “I’ve been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame twice (2005 with the O’Jays and 2009 with Little (Photo from the Classic Urban Harmony Archives) Anthony & the Imperials), the Vocal Group Hall of Fame (with both groups), the Pioneer R&B Hall of Fame (with Little An- today. The next day we went back to Ernie Martinelli and said thony & the Imperials) and the NAACP Hall of Fame (with the we were back together. Our first gig was to be a week-long O’Jays). Not a day goes by when I don’t hear one of the songs engagement at the Town Hill Supper Club, a place that I had I recorded on the radio. I’ve been very, very, very blessed.” once played with the Fantastics. We had two weeks before we Over the past year, we’ve documented Sammy opened. From the time we did that show at Town Hill, the Strain’s career with a series of articles on the Chips (Echoes of group never stopped working. “ the Past #101), the Fantastics (Echoes of the Past #102) and The Town Hall Supper Club was a well known venue the Imperials without Little Anthony (Echoes of the Past at Bedford Avenue and the Eastern Parkway in the Crown #103). -

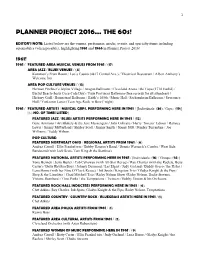

PLANNER PROJECT 2016... the 60S!

1 PLANNER PROJECT 2016... THE 60s! EDITOR’S NOTE: Listed below are the venues, performers, media, events, and specialty items including automobiles (when possible), highlighting 1961 and 1966 in Planner Project 2016! 1961! 1961 / FEATURED AREA MUSICAL VENUES FROM 1961 / (17) AREA JAZZ / BLUES VENUES / (4) Kornman’s Front Room / Leo’s Casino (4817 Central Ave.) / Theatrical Restaurant / Albert Anthony’s Welcome Inn AREA POP CULTURE VENUES / (13) Herman Pirchner’s Alpine Village / Aragon Ballroom / Cleveland Arena / the Copa (1710 Euclid) / Euclid Beach (hosts Coca-Cola Day) / Four Provinces Ballroom (free records for all attendees) / Hickory Grill / Homestead Ballroom / Keith’s 105th / Music Hall / Sachsenheim Ballroom / Severance Hall / Yorktown Lanes (Teen Age Rock ‘n Bowl’ night) 1961 / FEATURED ARTISTS / MUSICAL GRPS. PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (36) / Grps.: (19)] [(-) NO. OF TIMES LISTED] FEATURED JAZZ / BLUES ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / (12) Gene Ammons / Art Blakely & the Jazz Messengers / John Coltrane / Harry ‘Sweets’ Edison / Ramsey Lewis / Jimmy McPartland / Shirley Scott / Jimmy Smith / Sonny Stitt / Stanley Turrentine / Joe Williams / Teddy Wilson POP CULTURE: FEATURED NORTHEAST OHIO / REGIONAL ARTISTS FROM 1961 / (6) Andrea Carroll / Ellie Frankel trio / Bobby Hanson’s Band / Dennis Warnock’s Combo / West Side Bandstand (with Jack Scott, Tom King & the Starfires) FEATURED NATIONAL ARTISTS PERFORMING HERE IN 1961 / [Individuals: (16) / Groups: (14)] Tony Bennett / Jerry Butler / Cab Calloway (with All-Star -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 116 JULY 27TH, 2020 “Baby, there’s only two more days till tomorrow.” That’s from the Gary Wilson song, “I Wanna Take You On A Sea Cruise.” Gary, an outsider music legend, expresses what many of us are feeling these days. How many conversations have you had lately with people who ask, “what day is it?” How many times have you had to check, regardless of how busy or bored you are? Right now, I can’t tell you what the date is without looking at my Doug the Pug calendar. (I am quite aware of that big “Copper 116” note scrawled in the July 27 box though.) My sense of time has shifted and I know I’m not alone. It’s part of the new reality and an aspect maybe few of us would have foreseen. Well, as my friend Ed likes to say, “things change with time.” Except for the fact that every moment is precious. In this issue: Larry Schenbeck finds comfort and adventure in his music collection. John Seetoo concludes his interview with John Grado of Grado Labs. WL Woodward tells us about Memphis guitar legend Travis Wammack. Tom Gibbs finds solid hits from Sophia Portanet, Margo Price, Gerald Clayton and Gillian Welch. Anne E. Johnson listens to a difficult instrument to play: the natural horn, and digs Wanda Jackson, the Queen of Rockabilly. Ken hits the road with progressive rock masters Nektar. Audio shows are on hold? Rudy Radelic prepares you for when they’ll come back. Roy Hall tells of four weddings and a funeral. -

Issue No. 39 September/October 2016 3 Videogames Have Become Bonafide EYE Entertainment Franchises

Press Play LÉON Lewis Del Mar Luna Aura Marshmello NAO and more THE STORM ISSUE NO. 39 REPORT SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 EYE OF THE STORM Press Play: How videogames could save the music industry 5 STORM TRACKER Roadies Roll Call, Kiira Is Killing It, The Best and the Brightest 6 STORM FORECAST What to look forward to this month. Award Shows, Concert Tours, Album Releases, and more 7 STORM WARNING Our signature countdown of 20 buzzworthy bands and artists on our radar. 19 SOURCES & FOOTNOTES On the Cover: Martin Garrix. Photo provided by management ABOUT A LETTER THE STORM FROM THE REPORT EDITOR STORM = STRATEGIC TRACKING OF RELEVANT MEDIA Hello STORM Readers! The STORM Report is a compilation of up-and-coming bands and Videogames have become a lucrative channel artists who are worth watching. Only those showing the most for musicians seeking incremental revenue promising potential for future commercial success make it onto our as well as exposure to a captive and highly monthly list. engaged audience. Soundtracks for games include a varied combination of original How do we know? music scores, sound effects and licensed tracks. Artists from Journey (yes, Journey) Through correspondence with industry insiders and our own ravenous to Linkin Park have created gamified music media consumption, we spend our month gathering names of artists experiences to bring their songs to visual who are “bubbling under”. We then extensively vet this information, life. In the wake of Spotify announcing an analyzing an artist’s print & digital media coverage, social media entire section of its streaming platform growth, sales chart statistics, and various other checks and balances to dedicated to videogame music, we’ve used ensure that our list represents the cream of the crop. -

Dave Hartl's 2017 Top Ten (Or So) Most Influential Albums

Dave Hartl’s 2017 Top Ten (Or So) Most Influential Albums It’s time once again to look back and do that annual tradition of picking out the 10 or so most influential albums I heard in the past year. Not the most popular, or even the best, but what made me think the most as a musician. You can always go to http://www.davehartl.com/top10.html and look at other years’ postings. The links there go all the way back to 1998, when I started this with George Tucker. It’s a way of hearing about great music you might otherwise miss. If you want to contribute, please write to [email protected] with your own list and your contribution will be added to this document online for future downloads. This is why I do this! It always gives me some great recommendations for what to listen to that would be off my radar otherwise. So don’t be shy! Last year, Brian Groder, Jack Loughhead, and Kaz Yoshihara gave me some great things to listen to. 1.) John McLaughlin & the 4th Dimension: Live at Ronnie Scott’s 2017 saw the farewell American tour of the great guitarist John McLaughlin, who joined up with fellow guitarist Jimmy Herring for an unbelievable 3-set night concluding with pieces from his old Mahavishnu Orchestra days (you can see an entire concert at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPWa9F4UBQQ&t=19s, highly recommended!). This CD was recorded in London with McLaughlin’s working band of the last decade, the 4th Dimension, about 7 months ahead of the aforementioned American tour, but it shows a microcosm of that concept, opening with 1971’s Meeting of the Spirits and working through pieces showcasing the amazing drummer Ranjit Barot and his Indian classical influences, bassist Etienne M’Bappé’s multilevel constructions, and Gary Husband’s otherworldly synth textures, blowout chops, and energetic drumming.