Incinerated in the Flames Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-2019 წლების ანგარიში/Annual Report

რელიგიის საკითხთა STATE AGENCY FOR სახელმწიფო სააგენტო RELIGIOUS ISSUES 2018-2019 წლების ანგარიში/ANNUAL REPORT 2020 თბილისი TBILISI წინამდებარე გამოცემაში წარმოდგენილია რელიგიის საკითხთა სახელმწიფო სააგე- ნტოს მიერ 2018-2019 წლებში გაწეული საქმიანობის ანგარიში, რომელიც მოიცავს ქვეყა- ნაში რელიგიის თავისუფლების კუთხით არსებული ვითარების ანალიზს და იმ ძირითად ღონისძიებებს, რასაც სააგენტო ქვეყანაში რელიგიის თავისუფლების, შემწყნარებლური გარემოს განმტკიცებისთვის ახორციელებს. ანგარიშში განსაკუთრებული ყურადღებაა გამახვილებული საქართველოს ოკუპირებულ ტერიტორიებზე, სადაც ნადგურდება ქართული ეკლესია-მონასტრები და უხეშად ირღვე- ვა მკვიდრი მოსახლეობის უფლებები რელიგიის, გამოხატვისა და გადაადგილების თავი- სუფლების კუთხით. ანგარიშში მოცემულია ინფორმაცია სააგენტოს საქმიანობაზე „ადამიანის უფლებების დაცვის სამთავრობო სამოქმედო გეგმის“ ფარგლებში, ასევე ასახულია სახელმწიფოს მხრი- დან რელიგიური ორგანიზაციებისათვის გაწეული ფინანსური თუ სხვა სახის დახმარება და განხორციელებული პროექტები. This edition presents a report on the activities carried out by the State Agency for Religious Is- sues in 2018-2019, including analysis of the situation in the country regarding freedom of religion and those main events that the Agency is conducting to promote freedom of religion and a tolerant environment. In the report, particular attention is payed to the occupied territories of Georgia, where Georgian churches and monasteries are destroyed and the rights of indigenous peoples are severely violated in terms of freedom of religion, expression and movement. The report provides information on the Agency's activities within the framework of the “Action Plan of the Government of Georgia on the Protection of Human Rights”, as well as financial or other assistance provided by the state to religious organizations and projects implemented. რელიგიის საკითხთა სახელმწიფო სააგენტო 2018-2019 წლების ანგარიში სარჩევი 1. რელიგიისა და რწმენის თავისუფლება ოკუპირებულ ტერიტორიებზე ........................ 6 1.1. -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Georgia/Abkhazia

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH ARMS PROJECT HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH/HELSINKI March 1995 Vol. 7, No. 7 GEORGIA/ABKHAZIA: VIOLATIONS OF THE LAWS OF WAR AND RUSSIA'S ROLE IN THE CONFLICT CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY, RECOMMENDATIONS............................................................................................................5 EVOLUTION OF THE WAR.......................................................................................................................................6 The Role of the Russian Federation in the Conflict.........................................................................................7 RECOMMENDATIONS...............................................................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Republic of Georgia ..............................................................................................8 To the Commanders of the Abkhaz Forces .....................................................................................................8 To the Government of the Russian Federation................................................................................................8 To the Confederation of Mountain Peoples of the Caucasus...........................................................................9 To the United Nations .....................................................................................................................................9 To the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe..........................................................................9 -

BLACK SEA SUBMARINE VALLEYS – PATTERNS, SYSTEMS, NETWORKS Dan C

BLACK SEA SUBMARINE VALLEYS – PATTERNS, SYSTEMS, NETWORKS DAN C. JIPA1, NICOLAE PANIN1, CORNEL OLARIU2, CORNEL POP1 1National Institute of Marine Geology and Geo-Ecology (GeoEcoMar), 23-25 Dimitrie Onciul St., 024053 Bucharest, Romania 2Department of Geological Sciences, Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin, 2305 Speedway Stop, C1160, Austin, TX 78712-1692 Abstract. The article presents a detailed analysis of the underwater morphology of the entire Black Sea basin beyond the shelf break. The focus is on submarine valley systems on continental slope and rise zones, and partially in the abyssal plain area. The present research is among the very few studies that have undertaken a morphological analysis on a regional scale, for an entire marine basin. This achievement was possible by using the publicly available EMODnet bathymetric map of the Black Sea. The Black Sea submarine valleys networks are presented in a map-sketch. It includes 25 valley systems, 5 groups of simple first order channels, and other number of simple, not associated channels. The 25 valley systems are adding up more than 110 main channels and tributaries. Morphological description and analysis of each of the mapped systems is given – shape and plan view morphology, dimensions (length and surface) and slope gradient. Some considerations about the amount of sediments supplied by the valleys from the shelf to the basin floor, forming the deep-sea fans, are presented. For a more detailed and precise image of the Black Sea network of submarine valleys additional work would be necessary to cover the entire basin with a minimum standard network of modern bathymetric mapping and of high resolution seismic survey lines. -

Aw As Adjunct to Custom?

LAW AS ADJUNCT TO CUSTOM? Abkhaz custom and law in today’s state-building and ‘modernisation’ - (Studied through dispute resolution) DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND CONSERVATION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF KENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 12 FEBRUARY 2015 By Michael Costello Examiners: Professor Michael Fischer Associate Professor Jacob Rigi Supervisor: Lecturer Glenn Bowman 1 LAW AS ADJUNCT TO CUSTOM? The relationship between Abkhaz custom and law in today’s state-building and ‘modernisation’ - (Studied through dispute resolution) Abstract The setting for research is Abkhazia a small country south of the Caucasus Mountains and bordering Europe and the Near East. The Abkhaz hold onto custom – apswara – to make of state law an adjunct to custom as the state strives to strengthen its powers to ‘modernise’ along capitalist lines. This institution of a parallel-cum-interwoven and oppositional existence of practices and the laws questions the relationship of the two in a novel way. The bases of apswara are its concepts of communality and fairness. Profound transformations have followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the breakaway from and subsequent war with Georgia, none of which have brought the bright prospects that were hoped-for with independence. The element of hope in post-Soviet nostalgia provides pointers to what the Abkhaz seek to enact for their future, to decide the course of change that entertains the possibility of a non-capitalist modernisation route and a customary state. Apswara is founded on the direct participatory democracy of non-state regulation. It draws members of all ethnicities into the generation of nationalist self-awareness that transcends ethnicity and religions, and forms around sacred shrines and decisions taken by popular assemblies. -

Question on the Dominant Religion in Modern Abkhazia

ISSN 2414-1143 Научный альманах стран Причерноморья. 2016. Том 8. № 4 UDC 101 QUESTION ON THE DOMINANT RELIGION IN MODERN ABKHAZIA O. Zdorovtseva extern student. Institute of philosophy and social-political science Southern federal university. Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation [email protected] This study aims to show that Christianity is neither traditional nor dominant religion of Abkhazia in spite of the current official position of the state power and religious identity of the population in this issue. Objectives: 1) to show on the basis of historical and statistical data that in Abkhazia at the beginning of the twentieth century the Orthodoxy prevailed nominally and not really because of the actual Islamization of the population; 2) to show that modern statistics in relation to Orthodoxy as formal as in the early twentieth cen- tury due to the fact that the Abkhazians follow the Abkhaz traditional religion. According to the Statistical Yearbook of Russia of 1913 the Orthodox Christians in Abkhazia were in the majority – 85,14 %, Muslims – 11,12 %. Archival data only thirty-two years ago suggests the opposite: in Sukhumi, the Bzyb and Anguish administrative districts the proportion of Mohammedans was 85,48% of the entire population, that exceeded the number of Orthodox more than 70%, and in the whole province persons of the Muslim faith were in dominate. The data of the Statistical Yearbook, probably, have been achieved in the short time due to the quantitative extension of the number of formally baptized residents, essentially re- maining “in their opinion” religion. According to the 1897 census the majority of the population in Abkhazia were peasants – 848 per- sons per 1000 (for comparison students consisted of 64,1 people per 1000 people), the clergy – 23 281, 3 people in the whole province (+10 582,41 people engaged in worship and service in the liturgical buildings). -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily re ect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scienti c institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the rst time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

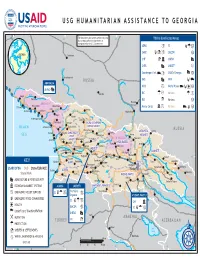

Georgia Program Maps 10/31/2008

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO GEORGIA 40° E 42° E The boundaries and names used on this map 44° E T'bilisi & Affected46° E Areas Majkop do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. ADRA a SC Ga I GEORGIA CARE a UMCOR a Cherkessk CHF IC UNFAO CaspianA Sea 44° CNFA A UNICEF J N 44° Kuban' Counterpart Int. Ea USAID/Georgia Aa N Karachayevsk RUSSIA FAO A WFP E ABKHAZIA E !0 Psou IOCC a World Vision Da !0 UNFAO A 0 Nal'chik IRC G J Various G a ! Gagra Bzyb' Groznyy RUSSIA 0 Pskhu IRD I Various a ! Nazran "ABKHAZIA" Novvy Afon Pitsunda 0 Omarishara Mercy Corps Ca Various E a ! Lata Sukhumi Mestia Gudauta!0 !0 Kodori Inguri Vladikavkaz Otap !0 Khaishi Kvemo-gulripsh Lentekhi !0 Tkvarcheli Dzhvari RACHA-LECHKHUMI-RACHA-LECHKHUMI- Terek BLACK Ochamchira Gali Tsalenjhikha KVEMOKVEMO SVANETISVANETI RUSSIA Khvanchkara Rioni MTSKHETA-MTSKHETA- Achilo Pichori Zugdidi SAMEGRELO-SAMEGRELO- Kvaisi Mleta SEA ZEMOZEMO Ambrolauri MTIANETIMTIANETI Pasanauri Alazani Khobi Tskhaltubo Tkibuli "SOUTH OSSETIA" Anaklia SVANETISVANETI Aragvi Qvirila SHIDASHIDA KARTLIKARTLI Senaki Kurta Artani Rioni Samtredia Kutaisi Chiatura Tskhinvali Poti IMERETIIMERETI Lanchkhuti Rioni !0 Akhalgori KAKHETIKAKHETI Chokhatauri Zestafoni Khashuri N Supsa Baghdati Dusheti N 42° Kareli Akhmeta Kvareli 42° Ozurgeti Gori Kaspi Borzhomi Lagodekhi KEY Kobuleti GURIAGURIA Bakhmaro Borjomi TBILISITBILISI Telavi Abastumani Mtskheta Gurdzhaani Belokany USAID/OFDA DoD State/EUR/ACE Atskuri T'bilisi Î! Batumi 0 AJARIAAJARIA Iori ! Vale Akhaltsikhe Zakataly State/PRM -

Short History of Abkhazia and Abkhazian-Georgian Relations

HISTORY AND CONTROVERSY: SHORT HISTORY OF ABKHAZIA AND ABKHAZIAN-GEORGIAN RELATIONS Svetlana Chervonnaya (Chapter 2 from the book” Conflict in the Caucasus: Georgia, Abkhazia and the Russian Shadow”, Glastonbury, 1994) Maps: Andrew Andersen, 2004-2007 Below I shall try to give a short review of the history of Abkhazia and Abkhazian-Georgian relations. No claims are made as to an in-depth study of the remote past nor as to any new discoveries. However, I feel it necessary to express my own point of view about the cardinal issues of Abkhazian history over which fierce political controversies have been raging and, as far as possible, to dispel the mythology that surrounds it. So much contradictory nonsense has been touted as truth: the twenty five centuries of Abkhazian statehood; the dual aboriginality of the Abkhazians; Abkhazia is Russia; Abkhazians are Georgians; Abkhazians came to Western Georgia in the 19th century; Abkhazians as bearers of Islamic fundamentalism; the wise Leninist national policy according to which Abkhazia should have been a union republic, and Stalin's pro-Georgian intrigues which turned the treaty-related Abkhazian republic into an autonomous one. Early Times to 1917. The Abkhazian people (self-designation Apsua) constitute one of the most ancient autochthonous inhabitants of the eastern Black Sea littoral. According to the last All-Union census, within the Abkhazian ASSR, whose total population reached 537,000, the Abkhazians (93,267 in 1989) numbered just above 17% - an obvious ethnic minority. With some difference in dialects (Abzhu - which forms the basis of the literary language, and Bzyb), and also in sub- ethnic groups (Abzhu; Gudauta, or Bzyb; Samurzaqano), ethnically, in social, cultural and psychological respects the Abkhazian people represent a historically formed stable community - a nation. -

Abkhazia – Historical Timeline

ABKHAZIA – HISTORICAL TIMELINE All sources used are specifically NOT Georgian so there is no bias (even though there is an abundance of Georgian sources from V century onwards) Period 2000BC – 100BC Today’s territory of Abkhazia is part of Western Georgian kingdom of Colchis, with capital Aee (Kutaisi - Kuta-Aee (Stone-Aee)). Territory populated by Georgian Chans (Laz-Mengrelians) and Svans. According to all historians of the time like Strabo (map on the left by F. Lasserre, French Strabo expert), Herodotus, and Pseudo-Skilak - Colchis of this period is populated solely by the Colkhs (Georgians). The same Georgian culture existed throughout Colchis. This is seen through archaeological findings in Abkhazia that are exactly the same as in the rest of western Georgia, with its capital in central Georgian city of Kutaisi. The fact that the centre of Colchian culture was Kutaisi is also seen in the Legend of Jason and the Argonauts (Golden Fleece). They travel through town and river of Phasis (modern day Poti / Rioni, in Mengrelia), to the city of Aee (Kutaisi – in Imereti), where the king of Colchis reigns, to obtain the Golden Fleece (method of obtaining gold by Georgian Svans where fleece is placed in a stream and gold gets caught in it). Strabo in his works Geography XI, II, 19 clearly shows that Georgian Svan tribes ruled the area of modern day Abkhazia – “… in Dioscurias (Sukhumi)…are the Soanes, who are superior in power, - indeed, one might almost say that they are foremost in courage and power. At any rate, they are masters of the peoples around them, and hold possession of the heights of the Caucasus above Dioscurias (Sukhumi). -

The Abkhazian and Mingrelian Principalities: Historical and Demographic Research A

Вестник СПбГУ. История. 2018. Т. 63. Вып. 4 The Abkhazian and Mingrelian Principalities: Historical and Demographic Research A. А. Cherkasov, L. A. Koroleva, S. N. Bratanovskii, A. Valleau For citation: Cherkasov A. А., Koroleva L. A., Bratanovskii S. N., Valleau A. The Abkhazian and Min- grelian Principalities: Historical and Demographic Research. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 2018, vol. 63, issue 4, рp. 1001–1016. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu02.2018.402 This article examines the historical and demographic aspects of the development of the Abkhazian and Mingrelian principalities within the Russian Empire. The attention is drawn to the territorial disputes among rulers over the ownership of Samurzakan. The sources used for this study include documents from the State archives of Krasnodar Krai (Krasnodar, Russian Federation), the Central state historical archive of Georgia (Tbilisi, Georgia), statistical data of the 1800s–1860s on Abkhazia, Mingrelia and Samurzakan, as well as memoirs and diaries of travelers. The authors came to the following conclusions: 1) the uprising of Shikh Mansur in 1785 led to the adoption of new religious rules among the population of Circassia and Abkhazia. As a result, Islam began to spread in Abkhazia. At the time, Islam did not, however, reach Samurzakan and Mingrelia. Both territories remained Christian; 2) as soon as the Abkhazian and Mingrelian principalities were annexed to the Russian Empire, the ruling princes started greatly overestimating the local population rates. They believed that there were on average at least 9–10 people per household on the territories they ruled. In reality, there were 4,7 people per household in Abkhazia and about 7 in Mingrelia; 3) the beginning of the process of decentralization, which was characteristic of the Circassian tribes, can be illustrated Aleksandr A. -

Ethno-Demographic History of Abkhazia, 1886 - 1989 by Daniel Müller

Ethno-demographic history of Abkhazia, 1886 - 1989 by Daniel Müller Chapter 15. Demography: The Abkhazians: A Handbook by George Hewitt (Editor) Demography has many aspects. With regard to the Abkhaz, their famed longevity comes immediately to mind. However, it is difficult to prove just how old one is when, at the supposed time of one’s birth, registration was the exception rather than the norm. It has been noted that in the (15 January) 1970 All-Union Census the number of people in some higher age cohorts was actually larger than had been the size of corresponding (eleven year younger) cohorts in the (15 January) 1959 Census. Unless we assume a pensioner-invasion of the USSR in between, this must caution us to realize that some people may have a tendency in old age to advance more rapidly in years than the rest of us!1 However, we shall not deal with this interesting matter here, nor with any other of the more classical topics of demography. What we shall restrict ourselves to here is what is in Russian so aptly termed ethno-demography (étnodemografia). This issue is controversial. Generally, Georgian and pro-Georgian writers try to prove the largest possible percentage of 'Georgians' (i.e., Kartvelians) in the territory that today is Abkhazia throughout history, whereas Abkhaz and pro-Abkhaz writers perform the process from an opposite point of view. We shall narrow our focus in the main to Abkhazia, treating the Abkhaz diaspora only in a cursory manner. Concentrating on the topic of Kartvelian versus Abkhaz dominance, we shall also allocate less space to the many other groups in Abkhazia’s history than would be desirable if space were no problem.