Theatrical Reviews Section

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curran San Francisco Announces Cast for the Bay Area Premiere of Soft Power a Play with a Musical by David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Curran Press Contact: Julie Richter, Charles Zukow Associates [email protected] | 415.296.0677 CURRAN SAN FRANCISCO ANNOUNCES CAST FOR THE BAY AREA PREMIERE OF SOFT POWER A PLAY WITH A MUSICAL BY DAVID HENRY HWANG AND JEANINE TESORI JUNE 20 – JULY 10, 2018 SAN FRANCISCO (March 6, 2018) – Today, Curran announced the cast of SOFT POWER, a play with a musical by David Henry Hwang (play and lyrics) and Jeanine Tesori (music and additional lyrics). SOFT POWER will make its Bay Area premiere at San Francisco’s Curran theater (445 Geary Street), June 20 – July 8, 2018. Produced by Center Theatre Group, SOFT POWER comes to Curran after its world premiere at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles from May 3 through June 10, 2018. Tickets for SOFT POWER are currently only available to #CURRAN2018 subscribers. Single tickets will be announced at a later date. With SOFT POWER, a contemporary comedy explodes into a musical fantasia in the first collaboration between two of America’s great theatre artists: Tony Award winners David Henry Hwang (M. Butterfly, Flower Drum Song) and Jeanine Tesori (Fun Home). Directed by Leigh Silverman (Violet) and choreographed by Sam Pinkleton (Natasha, Pierre, & the Great Comet of 1812), SOFT POWER rewinds our recent political history and plays it back, a century later, through the Chinese lens of a future, beloved East-meets-West musical. In the musical, a Chinese executive who is visiting America finds himself falling in love with a good-hearted U.S. leader as the power balance between their two countries shifts following the 2016 election. -

36Th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards Announcement

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Chris Kanarick [email protected] O: 646.893.4777 THE OFF-BROADWAY LEAGUE & LUCILLE LORTEL THEATRE TO PRESENT AN ORIGINAL FILMED PROGRAM FOR THE 36TH ANNUAL LUCILLE LORTEL AWARDS SPECIAL CELEBRATION OF THE OFF-BROADWAY COMMUNITY – ON-STAGE, BEHIND THE SCENES, AND IN THE AUDIENCE – WILL PREMIERE ON SUNDAY, MAY 2, 2021 New York, NY (April 14, 2021) – In an unprecedented year without live theatre to recognize, The Off- Broadway League and the Lucille Lortel Theatre will present the 2021 Lucille Lortel Awards as a celebration of all the people who create Off-Broadway excellence. The pre-taped special will honor the writers, actors, directors, choreographers, designers, musicians, stagehands, producers, theatre staff, and the audiences who all contribute to the incomparable magic of Off-Broadway theatre. Featuring testimonials from members of the community, as well as fun facts, video footage from past awards shows, the Lucille Lortel Vault, and more, the program will premiere Sunday, May 2, at 7:00PM on www.lortelawards.org and will, as always, be a benefit for The Actors Fund. The 36th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards will feature an appearance by Bebe Neuwirth, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees, The Actors Fund, as well as Quincy Tyler Bernstine, Tracee Chimo Pallero, Edmund Donovan, Scott Elliott, Will Eno, Stephen McKinley Henderson, Bill Irwin, Francis Jue, Judy Kuhn, Grace McLean, Annette O'Toole, Larry Owens, Tonya Pinkins, Daryl Roth, Kristen Schaal, Jeremy Shamos, Susan Stroman, Jason Tam, and more; a brand-new performance choreographed by actor and dancer Reed Luplau; comedy sketches by the improv group The Foundation; a monologue by Phillip Taratula as Pam Goldberg; a musical performance by Crystal Monee Hall, Allen René Louis, and Michael McElroy; and an original song by Bobby Daye in memory of Off-Broadway community members who lost their lives this past year. -

Spring Preview Spring World Premiere Previewchildren’S Or Teens’ Show SAN FRANCISCO

THEATRE BAY AREA 2016 spring preview spring World Premiere previewChildren’s or Teens’ Show SAN FRANCISCO 3Girls Theatre Company 3girlstheatre.org Thick House 1695 18th St. Z Below 470 Florida St. ` 2016 Salon Reading Series (By resident & associate playwrights) Thru 6/19 ` Low Hanging Fruit (By Robin Bradford) Z Below 7/8-30 ` 2016 New Works Festival Thick House David Naughton, Abby Haug & Lucas Coleman in 42nd Street Moon's production of 8/22-28 The Boys From Syracuse. Photo: David Allen 42nd Street Moon ` The Colored Museum American Conservatory Theater (By George C. Wolfe; dirs. Velina Brown, L. 42ndstreetmoon.org act-sf.org Peter Callender, Edris Cooper-Anifowoshe Geary Theater Eureka Theatre & Michael Gene Sullivan) 415 Geary St. 215 Jackson St. Thru 3/6 Strand Theater ` The Boys from Syracuse ` Antony and Cleopatra 1127 Market St. (By R. Rodgers, G. Abbott & L. Hart; dir. (By Shakespeare; dir. Jon Tracy) Greg MacKellan) 5/6-29 ` The Realistic Joneses 3/23-4/17 (By Will Eno; dir. Loretta Greco) Geary Theater ` The Most Happy Fella AlterTheater Ensemble 3/9-4/3 altertheater.org 4/27-5/15 ACT Costume Shop ` The Unfortunates (By Frank Loesser; dir. Cindy Goldfield) 1117 Market St. (By J. Beavers, K. Diaz, C. Hurt, I. Merrigan African-American Shakespeare & R.; dir. Shana Cooper) ` Vi [working title] Strand Theater Company (By Michelle Carter) Thru 4/10 african-americanshakes.org 6/2-19 Buriel Clay Theater 762 Fulton St. All information listed comes directly from publicity information supplied to Theatre Bay Area by the producing companies. Please contact companies or venues directly with questions. -

History and Background

History and Background Book by Lisa Kron, music by Jeanine Tesori Based on the graphic novel by Alison Bechdel SYNOPSIS Both refreshingly honest and wildly innovative, Fun Home is based on Vermont author Alison Bechdel’s acclaimed graphic memoir. As the show unfolds, meet Bechdel at three different life stages as she grows and grapples with her uniquely dysfunctional family, her sexuality, and her father’s secrets. ABOUT THE WRITERS LISA KRON was born and raised in Michigan. She is the daughter of Ann, a former community activist, and Walter, a German-born lawyer and Holocaust survivor. Kron spent much of her childhood feeling like an outsider because of her religion and sexuality. She attended Kalamazoo College before moving to New York in 1984, where she found success as both an actress and playwright. Many of Kron’s plays draw upon her childhood experiences. She earned early praise for her autobiographical plays 2.5 Minute Ride and 101 Humiliating Stories. In 1989, Kron co-founded the OBIE Award-winning theater company The Five Lesbian Brothers, a troupe that used humor to produce work from a feminist and lesbian perspective. Her play Well, which she both wrote and starred in, opened on Broadway in 2006. Kron was nominated for the Best Actress in a Play Tony Award for her work. JEANINE TESORI is the most honored female composer in musical theatre history. Upon receiving her degree in music from Barnard College, she worked as a musical theatre conductor before venturing into the art of composing in her 30s. She made her Broadway debut in 1995 when she composed the dance music for How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, and found her first major success with the off- Broadway musical Violet (Obie Award, Lucille Lortel Award), which was later produced on Broadway in 2014. -

Issue 3: Asian-American Experience During COVID-19

Issue 3: Asian-American Experience During COVID-19 A Note from Executive Vice President Amy Hungerford: Last year, my ofce launched this newsletter to showcase Arts & Sciences faculty accomplishments in the realms of justice, equity, and rights. Each quarterly issue features faculty members whose work engages a particular topic on the forefront of public consciousness. In this issue we explore the impact of COVID-19 on Asian- American communities, amid our national reckoning with the recent wave of anti- Asian racism and violence. While we are highlighting faculty who have been working in these elds, our hope is to bring the whole Arts & Sciences community into this critical conversation and to promote faculty collaboration across departments. Inside the issue, you'll nd highlights from interviews with professors David Henry Hwang and Mae Ngai, Faculty Spotlights, Columbia Events, and Recommended Reading. An Interview with Mae Ngai & David Henry Hwang Mae Ngai is Lung Family Professor of Asian American Studies and Professor of History at Columbia University. Mae is a U.S. legal and political historian whose research engages questions of immigration, citizenship, and nationalism. She is the author of Impossible Subjects (2004), which won six major book awards; The Lucky Ones (2010); and The Chinese Question (forthcoming Summer 2021). Mae recently published a piece on the history of anti-Asian racism in the U.S. in The Atlantic. David Henry Hwang is Associate Professor of Theatre and Playwriting Concentration Head at the Columbia University School of the Arts. David is a playwright, screenwriter, television writer, and librettist. Many of his stage works, including FOB, M. -

Jeanne Sakata Joel De La Fuente Lisa Rothe

PRESENTS BY Jeanne Sakata STARRING Joel de la Fuente SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Mikiko Suzuki MacAdams Margaret E. Weedon Cat Tate Starmer Daniel Kluger PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER CASTING Mary K. Botosan Pat McCorkle, Katja Zarolinski, CSA BERKSHIRE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE DIGITAL ADVERTISING NATIONAL PRESS REPRESENTATIVE Charlie Siedenburg The Pekoe Group Matt Ross Public Relations DIRECTED BY Lisa Rothe SPONSORED IN PART BY Carol and Alfred Maynard & Dick Ziter and Eric Reimer Hold These Truths was first produced in 2007 by East West Players in Los Angeles, California, under the title of Dawn’s Light: The Journey of Gordon Hirabayashi. It was commissioned in 2004 by Chay Yew, former Director of the Center Theater Group’s Asian Theatre Workshop, and further developed with the Lark Play Development Center, the New York Theatre Workshop, and the Epic Theatre Ensemble. Hold These Truths received its New York Premiere at the Epic Theatre Ensemble in October 2012. ST. GERMAIN STAGE MAY 22–JUNE 8, 2019 CAST Gordon Hirabayashi ............................................................................. Joel de la Fuente* STAFF Production Stage Manager .................................................................... Mary K. Botosan* Stage Management Intern ........................................................................ Melina Yelovich Master Electrician/Light Board Operator ...................................................Joey Rainone IV Sound Engineer .............................................................................................. -

Negotiating Images of the Chinese: Representations of Contemporary Chinese and Chinese Americans on US Television

Negotiating Images of the Chinese: Representations of Contemporary Chinese and Chinese Americans on US Television A Thesis Submitted to School of Geography, Politics, and Sociology For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cheng Qian September, 2019 !i Negotiating Images of the Chinese: Representations of Contemporary Chinese and Chinese Americans on US Television ABSTRACT China's rise has led to increased interest in the representation of Chinese culture and identity, espe- cially in Western popular culture. While Chinese and Chinese American characters are increasingly found in television and films, the literature on their media representation, especially in television dramas is limited. Most studies tend to focus on audience reception with little concentration on a show's substantive content or style. This thesis helps to fill the gap by exploring how Chinese and Chinese American characters are portrayed and how these portrayals effect audiences' attitude from both an in-group and out-group perspective. The thesis focuses on four popular US based television dramas aired between 2010 to 2018. Drawing on stereotype and stereotyping theories, applying visual analysis and critical discourse analysis, this thesis explores the main stereotypes of the Chinese, dhow they are presented, and their impact. I focus on the themes of enemies, model minor- ity, female representations, and the accepted others. Based on the idea that the media can both con- struct and reflect the beliefs and ideologies of a society I ask how representational practice and dis- cursive formations signify difference and 'otherness' in relation to Chinese and Chinese Americans. I argue that while there has been progress in the representation of Chinese and Chinese Americans, they are still underrepresented on the screen. -

Aida Tour Announcement Release

Disney Theatrical Productions Announces To Launch North American Tour Following Premiere at Paper Mill Playhouse February 4 – March 7, 2021 Re-Imagined New Production Directed by Schele Williams and Choreographed by Camille A Brown New York, NY - Disney Theatrical Productions (under the direction of Thomas Schumacher) proudly announces the launch of a new North American tour of Elton John and Tim Rice’s Tony®-winning Broadway smash Aida, following the premiere at Paper Mill Playhouse, February 4 – March 7, 2021. The production will play Charlotte, Chicago, Fort Worth, Kansas City, Los Angeles, Nashville, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., among other cities to be announced. 1 To receive news about the Aida North American tour, please sign-up for email alerts at AidaOnTour.com. For information on the Paper Mill run, visit PaperMill.org. The new production, updated and re-imagined, retains the beloved Tony and Grammy®-winning score and features a book revised by David Henry Hwang, who co-authored the acclaimed original production with Linda Woolverton and Robert Falls. The new Aida is directed by Schele Williams (a member of the original Broadway cast) and choreographed by Tony-nominee Camille A. Brown. Sets and costumes are by seven-time Tony winner Bob Crowley, and lighting is by six-time Tony winner Natasha Katz, who both won Tonys for their work on Aida in 2000. The music department includes Tony Award- recipient Jason Michael Webb (musical supervision), Tony Honor recipient Michael McElroy (vocal arrangements and co-incidental arranger), Jim Abbott (orchestrations) and Tony-winner Zane Mark (dance arrangements). Casting will be announced later this year. -

Informacja Prasowa AIDA-1.Pdf

TWÓRCY I REALIZATORZY Muzyka Teksty piosenek ELTON JOHN TIM RICE Libretto LINDA WOOLVERTON oraz ROBERT FALLS i DAVID HENRY HWANG Produkcja oryginalnej inscenizacji Disney Theatrical Productions Reżyseria WOJCIECH KĘPCZYŃSKI Przekład MICHAŁ WOJNAROWSKI Kierownictwo muzyczne, dyrygent JAKUB LUBOWICZ II reżyser SEBASTIAN GONCIARZ Scenografia MARIUSZ NAPIERAŁA Kostiumy DOROTA KOŁODYŃSKA Choreografia AGNIESZKA BRAŃSKA Reżyseria światła MARC HEINZ Reżyseria dźwięku PAWEŁ KACPRZYCKI, JAN KLUSZEWSKI Fryzury JAGA HUPAŁO Charakteryzacja SERGIUSZ OSMAŃSKI Kierownictwo techniczne ANNA WAŚ Asystent kierownika muzycznego PIOTR SKÓRKA Przygotowanie wokalne LENA ZUCHNIAK, JACEK KOTLARSKI Asystent scenografa MONIKA OSTROWSKA Współpraca kostiumologiczna AREK CHRUSTOWSKI Asystent kostiumografa ANNA ADAMEK Asystent choreografa MARIUSZ BOCIANOWSKI Asystent reżysera światła JASPER NIJHOLT Programowanie i realizacja światła oraz multimediów MICHAŁ MARDAS Programowanie i obsługa systemu VA MICHAŁ MAŁCZAK Asystentka EWELINA KULAWIUK Inspicjent TOMASZ NARLOCH Kierownictwo produkcji ALINA RÓŻANKIEWICZ Polska prapremiera 26 października 2019 roku Teatr Muzyczny ROMA Musical „AIDA” jest prezentowany na podstawie porozumienia z Music Theatre International (Europe) Limited, www.mtishows.eu 2 OBSADA AIDA Natalia Piotrowska Anastazja Simińska Basia Gąsienica Giewont RADAMES Jan Traczyk Marcin Franc Paweł Mielewczyk AMNERIS Zofia Nowakowska Agnieszka Przekupień Monika Rygasiewicz DŻOSER Jan Bzdawka Janusz Kruciński MEREB Piotr Janusz Michał Piprowski NEHEBKA Katarzyna -

Equity Tmplate

SEPTEMBER “The greatest tragedy in life 2011 is not death; the greatest tragedy takes place when our Volume 96 talents and capabilities are Number 7 underutilized and allowed to rust while we are living.” EQUITYNEWS —Amma A Publication of Actors’ Equity Association • NEWS FOR THE THEATRE PROFESSIONAL • www.actorsequity.org • Periodicals Postage Paid at New York, NY and Additional Mailing Offices First Membership Meeting of Production Contract Negotiations Update the 2011-2012 Season he negotiations for the a presentation of their proposals. side is listening intently to what Production Contract have The afternoon of the first day the other says and a better will be held on been in full swing since was devoted to the start of understanding about positions is Monday, October 10, 2011 – Western Region (11 am) T the last week of July. The two discussions and signaled that emerging. That open dialogue Monday, October 10, 2011 – Central Region (1 pm) sides have met more than a both sides were ready to do and the examination of the Friday, October 14, 2011 – Eastern Region (2 pm) dozen times and the talks are business. issues are allowing for these The Western Regional Meeting will convene on Monday, progressing slowly through each Negotiations can be a slow negotiations to be productive. October 10, 2011 at 11 am in the Bellamy Board Room in the of the proposals. process, as each side presents Still too early (at press time) to Equity office, 6755 Hollywood Boulevard, The first session set a new their point of view or holds report specifics, it is the intent of 5th Floor, Hollywood, CA. -

Read the Road Show Program

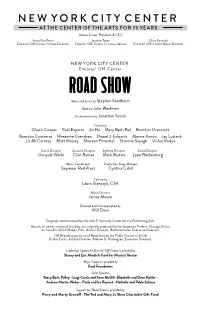

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

EQUITY News DECEMBER 2012

DECEMBER “Come, woo me, woo me; 2012 fornowIaminaholiday humor, and like enough Volume 97 to consent.” Number 9 —William Shakespeare EQUITYNEWS AsYou Like It,Act IV, Scene 1 A Publication of Actors’ Equity Association • NEWS FOR THE THEATRE PROFESSIONAL • www.actorsequity.org • Periodicals Postage Paid at New York, NY and Additional Mailing Offices Membership Meetings in All Regions 2013 Annual Election Gets Underway Will Select Nominating Committees he 2013 Equity elections pal, Chorus or Stage Manager. the Eastern Region (three Prin- Equity’s 2013 National Election gets underway at upcoming are just around the cor- You don’t even have to be at the cipals, two Chorus, and one Membership Meetings in each Region. The agenda for each Tner, and now is your Membership Meeting if you Stage Manager) and 11 mem- Meeting includes a Special Order of Business to nominate and chance to step up and be a part send a letter or email of accept- bers-at-large (seven Principals, select the membership portion of the Regional Nominating of the action. Even if you don’t ance to the election staff in your three Chorus and one Stage Committee. see yourself actually running for region’s office city before the Manager). office, you can still make your meeting and have someone The Central Regional Nomi- The EASTERN REGIONAL MEMBERSHIP MEETING will be held on mark on the 2013 Elections by nominate you at the meeting. nating Committee has ten Friday, January 11, 2013 at 2 pm serving on your Regional Nomi- Don’t worry if you haven’t members: four members select- in the Council Room (14th Floor) of the Equity Building nating Committee! served on a committee before– ed from the Central Regional 165 West 46th Street, New York Nominating Committees this is a terrific way to get your Board, Councillors and Officers feet wet, learn a lot and put your resident in the Central Region The agenda includes: The Nom Com (as it’s affec- experience to work for your (two Principals, one Chorus, • Presentation of the St.