Restriction of Speech Because of Its Content: the Peculiar Case of Subject-Matter Restrictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK Inc NI) Incorporating Planned Local TV and Temporary HD Muxes

As at 07 December 2020 FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK inc NI) incorporating planned Local TV and Temporary HD muxes 3PSB: Available from all transmitters (*primary and relay) 3 COM: From *80 primary transmitters only Temp HD - 25 Transmiters BBC A (PSB1) BBC A (PSB1) continued BBC B (PSB3) HD SDN (COM4) ARQIVA A (COM5) ARQIVA B (COM6) ARQIVA C (COM7) HD ARQIVA D (COM8) HD LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN 1 BBC ONE 65 TBN UK 12 QUEST 11 Sky Arts 22 Ideal World 64 Free Sports BBC RADIO: 1 BBC ONE NI Cambridge, Lincolnshire, 74 Shopping Quarter 13 E4 (Wales only) 17 Really 23 Dave ja vu 70 Quest Red+1 722 Merseyside, Oxford, 1 BBC ONE Scot Solent, Somerset, Surrey, 101 BBC 1 Scot HD 16 QVC 19 Dave 26 Yesterday 83 NOW XMAS Tyne Tees, WM 1 BBC ONE Wales 101 BBC 1 Wales HD 20 Drama 30 4Music 33 Sony Movies 86 More4+1 2 BBC TWO 101 BBC ONE HD 21 5 USA 35 Pick 36 QVC Beauty 88 TogetherTV+1 (00:00-21:00) 2 BBC TWO NI BBC RADIO: 101 BBC ONE NI HD 27 ITVBe 39 Quest Red 37 QVC Style 93 PBS America+1 726 BBC Solent Dorset 2 BBC TWO Wales BBC Stoke 102 BBC 2 Wales HD 28 ITV2 +1 42 Food Network 38 DMAX 96 Forces TV 7 BBC ALBA (Scot only) 102 BBC TWO HD 31 5 STAR 44 Gems TV 40 CBS Justice 106 BBC FOUR HD 9 BBC FOUR 102 BBC TWO NI HD 32 Paramount Network 46 Film4+1 43 HGTV 107 BBC NEWS HD Sony Movies Action 9 BBC SCOTLAND (Scot only) BBC RADIO: 103 ITV HD 41 47 Challenge 67 CBS Drama 111 QVC HD (exc Wales) 734 Essex, Northampton, CLOSED 24 BBC FOUR (Scot only) Sheffield, 103 ITV Wales HD 45 Channel 5+1 48 4Seven 71 Jewellery Maker 112 QVC Beauty HD 201 CBBC -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

BARB Quarterly Reach Report- Quarter Q3 2019 (BARB Weeks

BARB Quarterly Reach Report- Quarter Q3 2019 (BARB weeks 2658-2670) Individuals 4+ Weekly Reach Monthly Reach Quarterly Reach 000s % 000s % 000s % TOTAL TV 53719 89.0 58360 96.7 59678 98.9 4Music 2138 3.5 5779 9.6 11224 18.6 4seven 4379 7.3 11793 19.5 21643 35.9 5SELECT 2574 4.3 6663 11.0 11955 19.8 5Spike 4468 7.4 10115 16.8 16594 27.5 5Spike+1 199 0.3 625 1.0 1333 2.2 5STAR 5301 8.8 13032 21.6 22421 37.2 5STAR+1 643 1.1 2122 3.5 4759 7.9 5USA 3482 5.8 6742 11.2 10374 17.2 5USA+1 467 0.8 1242 2.1 2426 4.0 92 News 101 0.2 280 0.5 588 1.0 A1TV 101 0.2 285 0.5 627 1.0 Aaj Tak 164 0.3 364 0.6 698 1.2 ABN TV 105 0.2 259 0.4 548 0.9 ABP News 145 0.2 333 0.6 625 1.0 Akaal Channel 87 0.1 287 0.5 724 1.2 Alibi 1531 2.5 3383 5.6 5964 9.9 Alibi+1 299 0.5 740 1.2 1334 2.2 AMC 96 0.2 248 0.4 565 0.9 Animal Planet 405 0.7 1107 1.8 2542 4.2 Animal Planet+1 107 0.2 337 0.6 678 1.1 Arise News 43 0.1 133 0.2 336 0.6 ARY Family 119 0.2 331 0.5 804 1.3 ATN Bangla 101 0.2 243 0.4 481 0.8 B4U Movies 255 0.4 595 1.0 1021 1.7 B4U Music 226 0.4 571 0.9 1192 2.0 B4U Plus 91 0.2 309 0.5 766 1.3 BBC News 6774 11.2 11839 19.6 17310 28.7 BBC Parliament 990 1.6 2667 4.4 5430 9.0 BBC RB 1 469 0.8 1582 2.6 3987 6.6 BBC RB 601 609 1.0 1721 2.9 3457 5.7 BBC Scotland 1421 2.4 3216 5.3 5605 9.3 BBC1 39360 65.2 49428 81.9 54984 91.2 BBC2 27006 44.8 41055 68.1 49645 82.3 BBC4 8429 14.0 18385 30.5 28278 46.9 BET:BlackEntTv 163 0.3 552 0.9 1375 2.3 BLAZE 2181 3.6 4677 7.8 8098 13.4 Boomerang 685 1.1 1751 2.9 3429 5.7 Boomerang+1 266 0.4 790 1.3 1631 2.7 Box Hits 405 0.7 1247 -

CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2020 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit

KEY 1 Player 4 Full House PREMIUM CHANNELS CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2020 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit + 266 National Geographic 506 Sky Sports F1® HD 748 Create and Craft 933 BBC Radio Foyle HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET + 267 National Geographic +1 507 Sky Sports Action HD 755 Gems TV 934 BBC Radio NanGaidheal + 268 National Geographic HD 508 Sky Sports Arena HD 756 Jewellery Maker 936 BBC Radio Cymru 1. Match your package to the column 1 2 3 4 5 6 269 Together 509 Sky Sports News HD 757 TJC 937 BBC London 101 BBC One/HD* + 270 Sky HISTORY HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD 951 Absolute 80s 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel Sky One + 110 + 271 Sky HISTORY +1 511 Sky Sports Main Event INTERNATIONAL 952 Absolute Classic Rock 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as + 272 Sky HISTORY2 HD 512 Sky Sports Premier League 1 2 3 4 5 6 958 Capital part of a Personal Pick collection 273 PBS America 513 Sky Sports Football 800 Desi App Pack 959 Capital XTRA 274 Forces TV 514 Sky Sports Cricket 801 Star Gold HD 960 Radio X + 275 Love Nature HD 515 Sky Sports Golf 802 Star Bharat 963 Kiss FM 516 Sky Sports F1® 803 Star Plus HD + 167 TLC HD 276 Smithsonian Channel HD ENTERTAINMENT 517 Sky Sports Action 805 SONY TV ASIA HD ADULT 168 Investigation Discovery 277 Sky Documentaries HD 1 2 3 4 5 6 + 518 Sky Sports Arena 806 SONY MAX HD 100 Virgin Media Previews HD 169 Quest -

Watch German Politics Chauvin Verdict “Is Not

Watch German Chauvin verdict The high cost Is lying politics “is not justice” of free money always wrong? JULY 2021 COVER The pressure is everywhere to take the COVID-19 vaccine. Should you? (Gary Dorning/TRUMPET) JULY 2021 | VOL. 32, NO. 6 | CIRC. 241,917 77 percent of cdu members say their party has chosen the wrong man. The CDU’s pick for chancellor, Armin Laschet, and Chancellor Merkel FEATURES DEPARTMENTS FROM THE EDITOR 1 What Does Free Money Cost? 15 WORLDWATCH 28 Watch German Politics! INFOGRAPHIC SOCIETYWATCH 31 What Will Happen After The Value of a Dollar 18 Trump Regains Power 2 PRINCIPLES OF LIVING 33 Is Lying Always Wrong? 20 ‘Six Days Shall You Labor’ ‘This Verdict Is Not Justice’ 6 Hero Worship for Another The Woman Who Saved the DISCUSSION BOARD 34 Career Criminal 32 Man Who Saved the World 22 COMMENTARY 35 Report: Britain Is Not Racist COVER STORY 9 The Former Prophets: How History Becomes Prophecy 24 Gotten Your Jab Yet? THE KEY OF DAVID TELEVISION LOG 36 Where Are Vaccine The Real Rift Caused by Passports Leading? 12 the Royal Couple 26 Is Coronavirus the Mark of the Beast? 14 GETTY IMAGES GETTY Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Flurry’s Trumpet executive editor Stephen Regular news updates and alerts News and analysis weekly television program Flurry’s television program from our website to your inbox updated daily theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpetdaily theTrumpet.com/go/brief theTrumpet.com FROM THE EDITOR GERALD FLURRY Watch German Politics! ermany will vote for a new chancellor on Septem- party. -

Annex 2: Methodology

Small Screen: Big Debate – a five-year review of Public Service Broadcasting (2014- 2018) Annex 2: Methodology Publication date: 27 February 2020 Contents Section 1. Research survey methodology 1 2. TV output and spend analysis 3 3. TV and AV consumption analysis 9 4. Listening analysis: RAJAR 16 Annex 2: Methodology 1. Research survey methodology Technology Tracker The Technology Tracker is a quantitative face-to-face CAPI survey, measuring awareness, access, usage and attitudes towards fixed and mobile telecoms, internet, multi-channel TV, on-demand services, and radio/audio. The survey is conducted once a year (January-February) among UK adults, aged 16+ (c. 3,900 adults in 2019). The data are initially weighted to correct the over-representation of nations, regions and areas to produce a geographically representative sample. They are then weighted by age, gender, social class, working status, and region to match the known population profile. PSB Tracker The PSB Tracker is conducted using a mixed methodology with online and CAPI face-to-face data collection. The sample was split 50% online / 50% face-to-face. In 2019, a total of 3,130 interviews were conducted (2,188 in England; 313 in Scotland; 315 in Wales; 319 in Northern Ireland). There have been methodological changes over time. In 2014, the tracker was a telephone survey, between 2015 and 2017, it was a 75% online and 25% face-to-face approach and in 2018, the study moved to 50% online and 50% face-to-face. In 2018 and 2019, frequent occasional viewers (defined as those who say they are occasional viewers but watch PSB channels every day or most days) have also been included. -

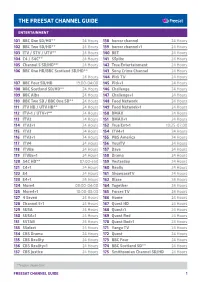

The Freesat Channel Guide

THE FREESAT CHANNEL GUIDE ENTERTAINMENT 101 BBC One SD/HD** 24 Hours 138 horror channel 24 Hours 102 BBC Two SD/HD** 24 Hours 139 horror channel+1 24 Hours 103 ITV / STV / UTV** 24 Hours 140 BET 24 Hours 104 C4 / S4C** 24 Hours 141 5Spike 24 Hours 105 Channel 5 SD/HD** 24 Hours 142 True Entertainment 24 Hours 106 BBC One HD/BBC Scotland SD/HD** 143 Sony Crime Channel 24 Hours 24 Hours 144 Pick TV 24 Hours 107 BBC Four SD/HD 19:00-04:00 145 Pick+1 24 Hours 108 BBC Scotland SD/HD** 24 Hours 146 Challenge 24 Hours 109 BBC Alba 24 Hours 147 Challenge+1 24 Hours 110 BBC Two SD / BBC One SD** 24 Hours 148 Food Network 24 Hours 111 ITV HD / UTV HD** 24 Hours 149 Food Network+1 24 Hours 112 ITV+1 / UTV+1** 24 Hours 150 DMAX 24 Hours 113 ITV2 24 Hours 151 DMAX+1 24 Hours 114 ITV2+1 24 Hours 152 True Ent+1 10:25-07:00 115 ITV3 24 Hours 154 ITV4+1 24 Hours 116 ITV3+1 24 Hours 155 PBS America 24 Hours 117 ITV4 24 Hours 156 YourTV 24 Hours 118 ITVBe 24 Hours 157 Dave 24 Hours 119 ITVBe+1 24 Hours 158 Drama 24 Hours 120 S4C HD** 07:00-end 159 Yesterday 24 Hours 121 C4+1 24 Hours 160 Really 24 Hours 122 E4 24 Hours 161 ShowcaseTV 24 Hours 123 E4+1 24 Hours 162 Blaze 24 Hours 124 More4 09:00-04:00 164 Together 24 Hours 125 More4+1 10:00-05:00 165 Forces TV 24 Hours 127 4 Seven 24 Hours 166 Home 24 Hours 128 Channel 5+1 24 Hours 167 Quest HD 24 Hours 129 5USA 24 Hours 168 Quest+1 24 Hours 130 5USA+1 24 Hours 169 Quest Red 24 Hours 131 5STAR 24 Hours 170 Quest Red+1 24 Hours 133 5Select 24 Hours 171 Yanga TV 24 Hours 134 CBS Drama 24 Hours 172 Quest 24 -

CBS Primetime Triple Threat Sponsorship Opportunity 2020

CBS Primetime Triple Threat Sponsorship Opportunity 2020 Channel Investment Start Platforms Available now On-Air Online The Opportunity Scheduling & Accreditation Sky Media and AMC Networks are excited to offer brands and advertisers the opportunity to sponsor primetime Primetime across CBS Justice, CBS Drama and CBS Reality. This • 1800-2400 package offers six hours a day across three channels of • Approx. 540 hours per month varied programming, from documentaries to docudramas, • Approx. 4.320 sponsorship credits per month from long-running serial dramas to classic cult series. • 15” Openers/Closers • 5” Break Bumpers (3 breaks per 1 hour show) About the Channels CBS Justice is one of the biggest general entertainment channels in the country. Viewers will be thrilled by the Example Programming twists and turns in these famous TV series such as NCIS and CSI Miami. Heroic characters from the many series and CBS Justice CBS Reality action and adventure films on offer will wow an audience • NCIS • Judge Judy who demand their TV with thrills. • NCIS: LA • Murder Wall • Scorpion • New Scotland Yard Files • CSI Miami • The Real Prime Suspect CBS Reality is as unpredictable as real life. Be captivated, shocked and entertained by this award-winning channel, CBS Drama which brings you compelling and heartfelt factual • Medium documentary series and specials that will shock and • Father Dowling Mysteries challenge, inspire and motivate. Audiences may not have • Perry Mason experienced the outrageous situations in Judge Judy, but Online they will certainly relate to the genuine human emotions shown. The drama doesn’t have to stop at on-air sponsorship. -

CBS Primetime Sponsorship Opportunity 2021

CBS Primetime Sponsorship Opportunity 2021 Channel Investment Start Platforms On-air Social Online Competition The Opportunity Scheduling & Accreditation Sky Media and AMC Networks are excited to offer brands Primetime and advertisers the opportunity to sponsor primetime • 1800-2400 across CBS Justice, CBS Drama and CBS Reality. This • Approx. 540 hours per month package offers six hours a day across three channels of Approx. 4.320 sponsorship credits per month varied programming, from documentaries to docudramas, • from long-running serial dramas to classic cult series. • 15” Openers/Closers • 5” Break Bumpers (3 breaks per 1 hour show) About the Channels CBS Justice is one of the biggest general entertainment Example Programming channels in the country. Viewers will be thrilled by the twists and turns in these famous TV series such as NCIS CBS Justice CBS Reality and CSI Miami. Heroic characters from the many detective • The Fugitive • Judge Judy and action series on offer will wow an audience who • CSI Cyber • Evidence of Evil demand their TV with thrills. • Perry Mason • Murder Wall • NCIS • Fatal Vows CBS Reality is as unpredictable as real life. Be captivated, CBS Drama shocked and entertained by this award-winning channel, • Medium which brings you authentic criminal cases and • Father Dowling Mysteries investigations expertly dissected using cutting-edge • Perry Mason forensic technologies that will shock and challenge, inspire and motivate. Audiences may not have experienced the Online outrageous situations in Judge Judy, but they will certainly relate to the genuine human emotions shown. The drama doesn’t have to stop at on-air sponsorship. As part of any sponsorship campaign on the channels, CBS can offer online display media as added value. -

Bbc One Hd Uk

UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ONE FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ONE HD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ONE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC TWO FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC TWO HD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC TWO SD UK: Entertainment: UK: ITV FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: ITV HD UK: Entertainment: UK: ITV SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 4 FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 4 HD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 4 SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 5 FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 5 HD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHANNEL 5 SD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ONE FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ONE HD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ONE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY WITNESS FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY WITNESS SD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ATLANTIC FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: SKY ATLANTIC SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 4SEVEN SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 5SELECT SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 5STAR SD UK: Entertainment: UK: 5US SD UK: Entertainment: UK: ALIBI FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: ALIBI SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC ALBA SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC FOUR FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC FOUR HD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC FOUR SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BBC RED BUTTON SD UK: Entertainment: UK: BET SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CBS DRAMA SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CBS JUSTICE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CBS REALITY SD UK: Entertainment: UK: CHALLENGE SD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL HD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL SD UK: Entertainment: UK: COMEDY CENTRAL EXTRA SD UK: Entertainment: UK: DAVE FHD UK: Entertainment: UK: DAVE SD -

CHANNEL GUIDE JUNE 2021 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit

KEY 1 Player 4 Full House PREMIUM CHANNELS CHANNEL GUIDE JUNE 2021 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit + 266 National Geographic 509 Sky Sports News HD INTERNATIONAL 951 Absolute 80s HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET + 267 National Geographic +1 510 Sky Sports Mix HD 1 2 3 4 5 6 952 Absolute Classic Rock + 268 National Geographic HD 511 Sky Sports Main Event 800 Desi App Pack 958 Capital 1. Match your package to the column 1 2 3 4 5 6 269 Together 512 Sky Sports Premier League 801 Utsav Gold HD 959 Capital XTRA 101 BBC One/HD* + 270 Sky HISTORY HD 513 Sky Sports Football 802 Utsav Bharat 960 Radio X 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel + 110 Sky One + 271 Sky HISTORY +1 514 Sky Sports Cricket 803 Utsav Plus HD 963 Kiss FM 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as + 272 Sky HISTORY2 HD 515 Sky Sports Golf 805 SONY TV HD ® part of a Personal Pick collection 273 PBS America 516 Sky Sports F1 806 SONY MAX HD ADULT 274 Forces TV 517 Sky Sports NFL 807 SONY SAB To PIN protect these channels, go to 276 Smithsonian Channel HD 518 Sky Sports Arena 808 SONY MAX 2 virginmedia.com/pin + 519 Sky Sports News 165 Pick 277 Sky Documentaries HD 809 Zee TV ENTERTAINMENT + 520 Sky Sports Mix 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 166 S4C HD* + 278 Sky Documentaries 810 Zee Cinema HD Sky Nature HD + 521 Eurosport 1 HD 969 Adult Previews 100 Virgin Media Previews HD + 167 TLC HD 279 815 B4U Movies -

Virgin Tv 360 Channel Guide

HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET KEY VIRGIN TV 360 1. Match your package to the column 4. If a channel is available in both SD 1 2 1 Mixit 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you and HD, and your package includes 101 BBC One/HD* the HD version, you will get that channel � 2 Maxit automatically see the HD content + 110 Sky One/HD CHANNEL GUIDE PREMIUM CHANNELS 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as part of a Personal Pick collection APRIL 2021 + PERSONAL PICK ENTERTAINMENT + 191 alibi +1 + 342 Kerrang! 625 NHKworld HD 865 BBC Two 1 2 192 CBS Justice 344 Vevo 870 ITV* 100 Virgin TV Highlights + 194 GOLD +1 345 Clubland TV KIDS 101 BBC One/HD* 196 More4 +1 346 Now 80s 1 2 RADIO 102 BBC Two HD* 197 CBS Drama 347 Now 90s 700 Kids TV On Demand All your radio channels can be found on the 103 ITV HD & STV HD & UTV HD* 200 Yesterday +1 348 Now 70s 701 CBBC HD homepage menu under the radio tile. 104 Channel 4/HD & S4C HD*� 201 CBS Reality +1 702 CBeebies HD Baby TV 105 Channel 5/HD� 202 Horror Channel +1 MOVIES 703 ADULT � 204 Netflix 1 2 + + 704 Cartoon Network/HD� 106 E4/HD 1 2 205 Prime Video 400 Virgin Movies & Store + + 705 Cartoon Network +1 107 BBC Four HD 968 A Message For Parents + 207 Sky Crime +1 401 Sky Cinema Premiere HD + + 706 Cartoonito 108 BBC One HD & BBC Scotland HD* 969 Adult Previews � + 209 Crime + Investigation HD 402 Sky Cinema Select HD + + 712 Nickelodeon/Nick HD� + 109 Sky One/HD 970 Nightly Television X � 213 Quest +1 403 Sky Cinema Hits HD 713 Nick +1 + 111 Sky Witness/HD + + 971 Babes & Brazzers 214 DMAX +1 404 Sky Cinema Greats HD Nick Jr.