The Deadlocked Supreme Court Fair Use Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President

Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2018: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President Updated October 9, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33225 Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to the Present Summary The process of appointing Supreme Court Justices has undergone changes over two centuries, but its most basic feature, the sharing of power between the President and Senate, has remained unchanged. To receive a lifetime appointment to the Court, a candidate must, under the “Appointments Clause” of the Constitution, first be nominated by the President and then confirmed by the Senate. A key role also has come to be played midway in the process by the Senate Judiciary Committee. Table 1 of this report lists and describes actions taken by the Senate, the Senate Judiciary Committee, and the President on all Supreme Court nominations, from 1789 through 2018. The table provides the name of each person nominated to the Court and the name of the President making the nomination. It also tracks the dates of formal actions taken, and time elapsing between these actions, by the Senate or Senate Judiciary Committee on each nomination, starting with the date that the Senate received the nomination from the President. Of the 44 Presidents in the history of the United States, 41 have made nominations to the Supreme Court. They made a total of 163 nominations, of which 126 (77%) received Senate confirmation. Also, on 12 occasions in the nation’s history, Presidents have made temporary recess appointments to the Court, without first submitting nominations to the Senate. -

Meet the Dean Nicholas W

BLSLawNotesThe Magazine of Brooklyn Law School | fall 2012 Meet the Dean Nicholas W. Allard becomes the Eighth Dean of Brooklyn Law School www.brooklaw.edu • 1 BLSLawNotes Vol. 17, No. 2 Editor-in-Chief Graphic Design Linda S. Harvey Ron Hester Design & Photography Assistant Dean for External Affairs Photographers Managing Editor Damion Edwards Andrea Strong ’94 Matilda Garrido Ron Hester Contributors Alan Perlman Diana Barnes-Brown Joe Vericker Bethany Blankley Tina Herrera Printer Alice Loeb Allied Printing Services, Inc. Andrea Polci Debra Sapp ’04 BLS LawNotes is published Andrea Strong ’94 semi-annually by Brooklyn Law School ClassNotes Editor for alumni, students, Caitlin Monck-Marcellino ’02 faculty and friends. Director of Alumni Relations Letters and Comments Faculty Highlights Editor We welcome letters and comments Bethany Blankley about articles in BLS LawNotes from Associate Director of Communications our graduates and friends. We will consider reprinting brief submissions Photo Editor in LawNotes and on our website. Matilda Garrido mailing address: Managing Editor BLS LawNotes 250 Joralemon Street Brooklyn, New York 11201 fax: 718-625-5242 email: [email protected] web: www.brooklaw.edu on the cover: Dean Nicholas W. Allard, with Brooklyn as his backdrop, photographed on the 22nd floor balcony of Feil Hall’s Forchelli Conference Center. 2 • BLSLawNotes | Fall 2012 CONTENTS FEATURES IN EVERY ISSUE 20 Meet the Dean: 3 Briefs From “Bedford Falls” to the Beltway Convocation; A Tech Revolution Grows in Brooklyn; to Brooklyn, Nicholas W. Allard Spotlight on OUTLaws; New Courses Bring Practice of Law into the Classroom; Janet Sinder Appointed Becomes the Eighth Dean of Library Director; Spring Events Roundup. -

Ross E. Davies, Professor, George Mason University School of Law 10

A CRANK ON THE COURT: THE PASSION OF JUSTICE WILLIAM R. DAY Ross E. Davies, Professor, George Mason University School of Law The Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, Fall 2009, pp. 94-107 (BRJ is a publication of SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research) George Mason University Law and Economics Research Paper Series 10-10 This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network at http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=1555017 **SABR_BRJ-38.2_final-v2:Layout 1 12/15/09 2:00 PM Page 94 BASEBALL AND LAW A Crank on the Court The Passion of Justice William R. Day Ross E. Davies here is an understandable tendency to date the Not surprisingly, there were plenty of other baseball Supreme Court’s involvement with baseball fans on the Court during, and even before, the period Tfrom 1922, when the Court decided Federal covered by McKenna’s (1898–1925), Day’s (1903–22), Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Pro- and Taft’s (1921–30) service. 13 Chief Justice Edward D. fessional Base Ball Clubs —the original baseball White (1894–1921) 14 and Justices John Marshall Har - antitrust-exemption case. 1 And there is a correspon - lan (1877–1911), 15 Horace H. Lurton (1910–14), 16 and ding tendency to dwell on William Howard Taft—he Mahlon Pitney (1912–22), 17 for example. And no doubt was chief justice when Federal Baseball was decided 2— a thorough search would turn up many more. 18 There is, when discussing early baseball fandom on the Court. -

) I by Supreme Court of the United States

BRARY & COURT. U. & ) I by Supreme Court of the United States OCTOBER TERM In the Matter of: Docket No. 645 JOHN DAVIS Petitioner; Oftice-Sujy*®# Cwjrt, U.S. F ILED vs, MAR 11 1969 STATE OP MISSISSIPPI i*HN f. «avis, clerk Respondent.. x Duplication or copying of this transcript by photographic, electrostatic or other facsimile means is prohibited under the order form agreement. Place Washington, D„ C. Date February 27 1969 ALDERSON REPORTING COMPANY, INC. 300 Seventh Street, S. W. Washington, D. C. NA 8-2345 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 REBUTTAL ARGUMENT; PAGE Melvyn Zarrf Esq», on behalf of 3 Petitioner 27 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 !! 12 13 14 15 13 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 2 October Terra, 1968 3 "X JOHN DAVIS, Petitioner; 6 vs, No® 645 7 STATE OF MISSISSIPPI , a Respondent, 9 !0 Washington, D® C. February 27, 1969 11 The above-entitled matter came on for further 12 argument at 10:10 a.in, 13 BEFORE: 14 EARL WARREN, Chief Justice 15 HUGO L« BLACK, Associate Justice WILLIAM O, DOUGLAS, Associate Justice 16 JOHN M. HARLAN, Associate Justice WILLIAM J, BRENNAN, JR®, Associate Justice 17 POTTER STEWART, Associate Justice BYRON R, WHITE, Associate Justice 18 THURGOOD MARSHALL, Associate'Justice 19 APPEARANCES: 20 MELVYN ZARR, Esq. 10 Columbus Circle 21 New York, N. Y. 10019 22 G. GARLAND LYELL, JR., Esq, Assistant Attorney General 23 State of Mississippi Hew Capitol Building 24 Jackson, Mississippi 23 26 P R 0 C E E D I N G S MR. -

Tales from the Blackmun Papers: a Fuller Appreciation of Harry Blackmun's Judicial Legacy

Missouri Law Review Volume 70 Issue 4 Fall 2005 Article 7 Fall 2005 Tales from the Blackmun Papers: A Fuller Appreciation of Harry Blackmun's Judicial Legacy Joseph F. Kobylka Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph F. Kobylka, Tales from the Blackmun Papers: A Fuller Appreciation of Harry Blackmun's Judicial Legacy, 70 MO. L. REV. (2005) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol70/iss4/7 This Conference is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kobylka: Kobylka: Tales from the Blackmun Papers: Tales from the Blackmun Papers: A Fuller Appreciation of Harry Blackmun's Judicial Legacy Joseph F. Kobylka' This right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment's concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or, as the District Court determined, in the Ninth Amendment's reservation of rights to the people, is broad to encompass a woman's decision whether or not to termi- enough 2 nate her pregnancy. - Justice Harry A. Blackmun, Roe v. Wade I believe we must analyze respondent Hardwick's claim in the light of the values that underlie the constitutional right to privacy. If that right means anything, it means that, before Georgia can prosecute its citizens for making choices about the most intimate aspects of their lives, it must do more than assert that the choice they have made3 is an "'abominable crime not fit to be named among Christians.' - Justice Harry A. -

FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK Inc NI) Incorporating Planned Local TV and Temporary HD Muxes

As at 07 December 2020 FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK inc NI) incorporating planned Local TV and Temporary HD muxes 3PSB: Available from all transmitters (*primary and relay) 3 COM: From *80 primary transmitters only Temp HD - 25 Transmiters BBC A (PSB1) BBC A (PSB1) continued BBC B (PSB3) HD SDN (COM4) ARQIVA A (COM5) ARQIVA B (COM6) ARQIVA C (COM7) HD ARQIVA D (COM8) HD LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN 1 BBC ONE 65 TBN UK 12 QUEST 11 Sky Arts 22 Ideal World 64 Free Sports BBC RADIO: 1 BBC ONE NI Cambridge, Lincolnshire, 74 Shopping Quarter 13 E4 (Wales only) 17 Really 23 Dave ja vu 70 Quest Red+1 722 Merseyside, Oxford, 1 BBC ONE Scot Solent, Somerset, Surrey, 101 BBC 1 Scot HD 16 QVC 19 Dave 26 Yesterday 83 NOW XMAS Tyne Tees, WM 1 BBC ONE Wales 101 BBC 1 Wales HD 20 Drama 30 4Music 33 Sony Movies 86 More4+1 2 BBC TWO 101 BBC ONE HD 21 5 USA 35 Pick 36 QVC Beauty 88 TogetherTV+1 (00:00-21:00) 2 BBC TWO NI BBC RADIO: 101 BBC ONE NI HD 27 ITVBe 39 Quest Red 37 QVC Style 93 PBS America+1 726 BBC Solent Dorset 2 BBC TWO Wales BBC Stoke 102 BBC 2 Wales HD 28 ITV2 +1 42 Food Network 38 DMAX 96 Forces TV 7 BBC ALBA (Scot only) 102 BBC TWO HD 31 5 STAR 44 Gems TV 40 CBS Justice 106 BBC FOUR HD 9 BBC FOUR 102 BBC TWO NI HD 32 Paramount Network 46 Film4+1 43 HGTV 107 BBC NEWS HD Sony Movies Action 9 BBC SCOTLAND (Scot only) BBC RADIO: 103 ITV HD 41 47 Challenge 67 CBS Drama 111 QVC HD (exc Wales) 734 Essex, Northampton, CLOSED 24 BBC FOUR (Scot only) Sheffield, 103 ITV Wales HD 45 Channel 5+1 48 4Seven 71 Jewellery Maker 112 QVC Beauty HD 201 CBBC -

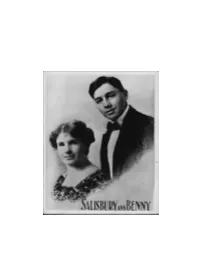

The Vaudeville Years – 1911 to 1932

Revision Date: May 17, 2020 Garth Johnson Jack Benny Day By Day: The Quick Reference Calendar Volume One: The Vaudeville Years – 1911 to 1932 Salisbury and Benny From Grand Opera To Ragtime Season One (1911) In this section I try to answer some of the “origin story” questions, but unfortunately the answers remain a mystery including - Leaving Waukegan - First Show - The Kublik Conflict Salisbury and Benny From Grand Opera to Ragtime Cora Folsom Salisbury and Benny Kubelsky were working in the orchestra pit of the Barrison Theater, in Waukegan, Illinois when it was sold and closed in 1911. Barrison Theater and Carnegie Library, Waukegan Illinois [“Waukegan” (Arcadia Publishing 2000 ISBN 9780738508368) Waukegan Historical Society] The Marx Brothers had just played the town with their act “Fun In Hi-Skool” in July and their mother/manager Mini had suggested Benny go on the road with them, but his parents said he could not. At seventeen, he was too young and impressionable for the travelling lifestyle. Cora, needing work to take care of her ailing mother, and seeing the potential in the young violinist, managed to persuade Benny’s parents a few weeks later that she would look out for him, and being the same age as the Kubelsky’s they relented. So it was with tears, reservations and anticipation about the future that seventeen year old Benny Kubelsky left Waukegan and began his career in show business. The acts first stop, according to Benny, was Gary Indiana and he relates the story of leaving Waukegan for that first time in Irving Fein’s book, “Jack Benny an Intimate Biography.” That may be what Benny recalls as the first show away from home, but a bill and notice for August 19, 1911 in the Racine Daily Journal, Racine Wisconsin, advertising “Salisbury and Kribelsky” appearing at the Racine Theater is currently the earliest documented appearance of the act. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

The Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States Hearings and Reports on the Successful and Unsuccessful Nominations Now Includes the Kavanaugh and Preliminary Barrett Volumes! This online set contains all existing Senate documents for 1916 to date, as a result of the hearings and subsequent hearings on Supreme Court nominations� Included in the volumes are hearings never before made public! The series began with three volumes devoted to the controversial confirmation of Louis Brandeis, the first nominee subject to public hearings. The most recent complete volumes cover Justice Kavanaugh. After two years, the Judiciary Committee had finally released Kavanaugh’s nomination hearings, so we’ve been able to complete the online volumes� The material generated by Kavanaugh’s nomination was so voluminous that it takes up 8 volumes� The definitive documentary history of the nominations and confirmation process, this ongoing series covers both successful and unsuccessful nominations� As a measure of its importance, it is now consulted by staff of the Senate Judiciary Committee as nominees are considered� Check your holdings and complete your print set! Volume 27 (1 volume) 2021 Amy Coney Barrett �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������Online Only Volume 26 (8 volumes) - 2021 Brett Kavanaugh ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������Online Only Volume 25 (2 books) - 2018 Neil M� Gorsuch ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������$380�00 -

Potter Stewart: Just a Lawyer Russell W

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Santa Clara University School of Law Santa Clara Law Review Volume 25 | Number 3 Article 1 1-1-1985 Potter Stewart: Just a Lawyer Russell W. Galloway Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Russell W. Galloway Jr., Potter Stewart: Just a Lawyer, 25 Santa Clara L. Rev. 523 (1985). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol25/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES POTTER STEWART: JUST A LAWYER Russell W. Galloway, Jr.* I. INTRODUCTION Retired Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart died on Decem- ber 7, 1985. Stewart was a member of the United States Supreme Court from 1958 to 1981. The purpose of this article is to review Stewart's illustrious career and his contributions during more than two decades of Supreme Court history. II. POTTER STEWART, CINCINNATI REPUBLICAN (1915-58) Potter Stewart was born January 23, 1915 into a family which lived in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father was a Republican politician, who served as Mayor of Cincinnati and Justice of the Ohio Supreme Court. Stewart received an impressive education at University School in Cincinnati at Hotchkiss School, and at Yale University, where he was class orator and received numerous honors; University of Cam- bridge; and Yale Law School, where he achieved an "outstanding record."' After graduating from Yale, Stewart practiced law in New York City (1941-42, 1945-47) with time out for service in the Navy during World War II. -

BARB Quarterly Reach Report- Quarter Q3 2019 (BARB Weeks

BARB Quarterly Reach Report- Quarter Q3 2019 (BARB weeks 2658-2670) Individuals 4+ Weekly Reach Monthly Reach Quarterly Reach 000s % 000s % 000s % TOTAL TV 53719 89.0 58360 96.7 59678 98.9 4Music 2138 3.5 5779 9.6 11224 18.6 4seven 4379 7.3 11793 19.5 21643 35.9 5SELECT 2574 4.3 6663 11.0 11955 19.8 5Spike 4468 7.4 10115 16.8 16594 27.5 5Spike+1 199 0.3 625 1.0 1333 2.2 5STAR 5301 8.8 13032 21.6 22421 37.2 5STAR+1 643 1.1 2122 3.5 4759 7.9 5USA 3482 5.8 6742 11.2 10374 17.2 5USA+1 467 0.8 1242 2.1 2426 4.0 92 News 101 0.2 280 0.5 588 1.0 A1TV 101 0.2 285 0.5 627 1.0 Aaj Tak 164 0.3 364 0.6 698 1.2 ABN TV 105 0.2 259 0.4 548 0.9 ABP News 145 0.2 333 0.6 625 1.0 Akaal Channel 87 0.1 287 0.5 724 1.2 Alibi 1531 2.5 3383 5.6 5964 9.9 Alibi+1 299 0.5 740 1.2 1334 2.2 AMC 96 0.2 248 0.4 565 0.9 Animal Planet 405 0.7 1107 1.8 2542 4.2 Animal Planet+1 107 0.2 337 0.6 678 1.1 Arise News 43 0.1 133 0.2 336 0.6 ARY Family 119 0.2 331 0.5 804 1.3 ATN Bangla 101 0.2 243 0.4 481 0.8 B4U Movies 255 0.4 595 1.0 1021 1.7 B4U Music 226 0.4 571 0.9 1192 2.0 B4U Plus 91 0.2 309 0.5 766 1.3 BBC News 6774 11.2 11839 19.6 17310 28.7 BBC Parliament 990 1.6 2667 4.4 5430 9.0 BBC RB 1 469 0.8 1582 2.6 3987 6.6 BBC RB 601 609 1.0 1721 2.9 3457 5.7 BBC Scotland 1421 2.4 3216 5.3 5605 9.3 BBC1 39360 65.2 49428 81.9 54984 91.2 BBC2 27006 44.8 41055 68.1 49645 82.3 BBC4 8429 14.0 18385 30.5 28278 46.9 BET:BlackEntTv 163 0.3 552 0.9 1375 2.3 BLAZE 2181 3.6 4677 7.8 8098 13.4 Boomerang 685 1.1 1751 2.9 3429 5.7 Boomerang+1 266 0.4 790 1.3 1631 2.7 Box Hits 405 0.7 1247 -

CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2020 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit

KEY 1 Player 4 Full House PREMIUM CHANNELS CHANNEL GUIDE AUGUST 2020 2 Mix 5 Mixit + PERSONAL PICK 3 Fun 6 Maxit + 266 National Geographic 506 Sky Sports F1® HD 748 Create and Craft 933 BBC Radio Foyle HOW TO FIND WHICH CHANNELS YOU CAN GET + 267 National Geographic +1 507 Sky Sports Action HD 755 Gems TV 934 BBC Radio NanGaidheal + 268 National Geographic HD 508 Sky Sports Arena HD 756 Jewellery Maker 936 BBC Radio Cymru 1. Match your package to the column 1 2 3 4 5 6 269 Together 509 Sky Sports News HD 757 TJC 937 BBC London 101 BBC One/HD* + 270 Sky HISTORY HD 510 Sky Sports Mix HD 951 Absolute 80s 2. If there’s a tick in your column, you get that channel Sky One + 110 + 271 Sky HISTORY +1 511 Sky Sports Main Event INTERNATIONAL 952 Absolute Classic Rock 3. If there’s a plus sign, it’s available as + 272 Sky HISTORY2 HD 512 Sky Sports Premier League 1 2 3 4 5 6 958 Capital part of a Personal Pick collection 273 PBS America 513 Sky Sports Football 800 Desi App Pack 959 Capital XTRA 274 Forces TV 514 Sky Sports Cricket 801 Star Gold HD 960 Radio X + 275 Love Nature HD 515 Sky Sports Golf 802 Star Bharat 963 Kiss FM 516 Sky Sports F1® 803 Star Plus HD + 167 TLC HD 276 Smithsonian Channel HD ENTERTAINMENT 517 Sky Sports Action 805 SONY TV ASIA HD ADULT 168 Investigation Discovery 277 Sky Documentaries HD 1 2 3 4 5 6 + 518 Sky Sports Arena 806 SONY MAX HD 100 Virgin Media Previews HD 169 Quest