Ilo Working Paper Cover.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resettlement Plan India: Maharashtra State Road Improvement Project

Resettlement Plan November 2019 India: Maharashtra State Road Improvement Project Improvement of road Shrirampur Vaijapur Risod Washim Pusad Mahagaon Fulsawangi Mandvi Road SH-51 Km (Section Washim to Pusad Shivaji Chowk) Km 242/200 to 298/249 (Package- EPC -5) Prepared by Public Works Department, Government of Maharashtra for the Asian Development Bank. ii CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1stAugust 2019) Currency unit – Indian rupees (₹) ₹1.00 = $0.0144 $1.00 = ₹69.47 NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of India and its agencies ends on 31 March. “FY” before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2019 ends on 31 March 2019. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AP Affected Person ARO Assistant Resettlement Officer AE Assistant Engineer BPL Below Poverty Line BSR Basic Schedule of Rates CAP Corrective Action Plan CoI Corridor of Impact CPR Common Property Resources CE •Chief Engineer DC District Collector DLAO District Land Acquisition Officer DP Displaced -

Oct Nov 2006

Dams, Rivers & People VOL 4 ISSUE 9-10 OCT-NOV 2006 Rs 15/- Lead Piece Climate Change is Here – when will we wake up? There is increasing evidence that shows that Another recent report, titled Feeling the Heat from the ? climate change is already here. It is already Christian development agency Tearfund predicts that affecting the rainfall, floods, droughts, sea- Climate change threatens supplies of water for millions levels, land erosion and so on. of people in poorer countries. By 2050, five times as much land is likely to be under "extreme" drought as The frequency of extreme weather incidents is clearly now. "It's the extremes of water which are going to increasing, the unprecedented floods in Mumbai and provide the biggest threat to the developing world from Gujarat in 2005 and 2006, the unprecedented floods in climate change… droughts will tend to be longer, and Barmer this year the unusual rainfall deficit in Bihar and that's very bad news. Extreme droughts currently cover Assam this year are only a few of the recent incidents. about 2% of the world's land area, and that is going to 2005 has already been declared the warmest year in spread to about 10% by 2050." it said. The positive side recent times. of the Tearfund report is that simple measures to A recent study at the School of Oceanographic Studies "climate-proof" water problems, both drought and flood, of Jadavpur University (The Hindustan Times 011106) have proven to be very effective in some areas. In Niger, says that 70 000 people would be affected in the eastern the charity says that building low, stone dykes across and western part of the Suderbans due to rising sea contours has helped prevent runoff and get more water levels. -

Agricultural Trends in Yavatmal Maharashtra - a District Level Analysis Sanjay Tupe* and Vaishali Joshi

Agro Economist - An International Journal Citation: AE: 7(1): 45-49, June 2020 DOI: 10.30954/2394-8159.01.2020.7 Agricultural Trends in Yavatmal Maharashtra - A District Level Analysis Sanjay Tupe* and Vaishali Joshi RNC Arts, JDB Commerce and NSC Science College Nashik Road, Nashik-422101, India *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 18-07-2020 Revised: 23-07-2020 Accepted: 15-10-2020 ABSTRACT This paper attempts to assess the changes in cropping pattern in Yavatmal district for the period from 1991 to 2010. We divide the period into two distinct periods: 1991-2000 and 2001-2010. The trends in the production of cereal crops, pulses and cash crops were observed using mean comparison t test and dummy variable regression model. The statistical and simple econometric exercises support the noticeable change occurred in the cropping pattern in the Yavatmal district during the period of economic reforms. The production of wheat was increased marginally during the period, but production of jowar crops drastically declined. The crops such as soybean and sunflower took overjowar during the study period. The trend showing decrease in overall production of cereals is a cause of concern for the government in particular and public in general. If the trend continues, it would be worrisome in terms of production of traditional crops. Keywords: Cropping pattern, trends, Maharashtra, economic reforms Maharashtra has more heterogeneity in crop consists of 16 Talukas. It is a major cotton producing production and cropping pattern arising from its district of Maharashtra. The district boundary varied agro-climatic conditions. Cropping pattern in touches five districts of Maharashtra namely the state varies from region to region. -

Maharashtra Village Social Transformation Mission

MAHARASHTRA VILLAGE SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION MISSION January 2018 DEBRIEF JANUARY 31, 2018 VILLAGE SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION FOUNDATION Mumbai-400 021 Contents Highlights from the Field ................................................................................................... 2 Amravati District ................................................................................................................ 2 Yavatmal District ................................................................................................................ 3 Raigad District ..................................................................................................................... 6 Aurangabad District ........................................................................................................... 7 Wardha District ................................................................................................................... 9 Nandurbar District ........................................................................................................... 12 Gadchiroli District ............................................................................................................ 15 Chandrapur District ......................................................................................................... 18 Nanded District ................................................................................................................. 20 Parbhani District ............................................................................................................. -

Annual Plan 2009-10

INDEX ANNUAL PLAN 2014-15 PART-I Chapter Subject Page No. No. Section – I General 1 Annual Plan 2014-15 – At a Glance 1-3 2 Economic Outline of Maharashtra 4-6 3 Planning Process 7-12 4 Central Assistance/Institutional Finance External Aided 13-17 Projects 5 Decentralization of Planning (District Planning) 18-20 6 Schedule Caste Sub-Plan 21-24 7 Tribal Sub Plan 25-28 8 Statutory Development Boards and Removal of Backlog 29-35 9 Woman and Child Development 36-42 10 Western Ghat and Hilly Area Development Programme 43-47 11 Human Development Index 48-50 Section 2 Sector wise 1 Agriculture and Allied Services 1-55 2 Rural Development 56-62 3 Special Area Development Programme 63 4 Water Resources and Flood Control 64-65 5 Power Development 66-79 6 Industry and Mining 80-94 7 Transport and Communication 95-102 8 Science, Technology and Environment 103-111 9 General Economic Services 112-125 10 Social and Community Services 126-237 11 General Services 238-246 ANNUAL PLAN 2014-15 AT A GLANCE Introduction: 1.1.1 Preparation and implementation of Five Year Plans and Annual Plans is one of the most important instruments for General Economic Development of the State. The main objective of planning is to create employment opportunities, improve standard of living of the people below the poverty line, and attain self-reliance and creation to infrastructure. 1.1.2 Size of Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-12) was determined at Rs.1,27,538/- crore. However, sum of the Annual Plans from year 2007-08 to 2011-12 sanctioned by the Planning Commission arrived actually at Rs.1,61,124/- crore. -

Government of Maharashtra Revenue and Forest Department Government Order No.: FLD-2021/CR-32/F-10 Mantralaya, Mumbai 400 032 Date: 09.03.2021 Reference: 1

Forest Land-Yavatmal Black topping and Improvement of Digras- Pusad-Darvha road joining Pusad Taluka Head Quarter to Yavatmal District, Tal. Pusad, Digras, Darvha, Ner, Dist. Yavatmal (Design Chainage km 98/380 to km 98/480) Government of Maharashtra Revenue and Forest Department Government Order No.: FLD-2021/CR-32/F-10 Mantralaya, Mumbai 400 032 Date: 09.03.2021 Reference: 1. Revenue and Forest Department, Government of Maharashtra Circular No. FLD-2019/C.R.76/F-10, dt.03.05.2019. 2. Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests and Nodal Officer, Maharashtra State, Nagpur Letter No. Desk-17/NC/I/C.R.41/277/20-21, dt.23.07.2020. 3. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, New Delhi Letter No. FC-11/117/2019-FC, dt.09.11.2020 Preamble: Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests and Nodal Officer, Maharashtra State, Nagpur, vide letter under reference No.2 has submitted a proposal to the State Government for black topping and improvement of Digras- Pusad-Darvha road joining Pusad Taluka Head Quarter to Yavatmal District, Tal. Pusad, Digras, Darvha, Ner, Dist. Yavatmal (Design Chainage km 98/380 to km 98/480), which is received from the Executive Engineer, Public Works Division, Pusad. After careful consideration and scrutiny of the proposal, this Government is pleased to grant approval for the aforesaid proposal. Government Order: The Deputy Conservator of Forests, Pusad Forest Division, Pusad has certified that the road under reference is existing from prior to 1980. Hence, in exercise of powers conferred to the State Government, vide MoEF&CC, Government of India's Handbook of Guidelines for effective and transparent implementation of the provisions of Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 [Chapter-11, Para-11.1 (iii) & 11.6] and letter under reference No.3, Government of Maharashtra is pleased to grant approval for black topping and improvement of Digras- Pusad-Darvha road joining Pusad Taluka Head Quarter to Yavatmal District, Tal. -

(River/Creek) Station Name Water Body Latitude Longitude NWMP

NWMP STATION DETAILS ( GEMS / MINARS ) SURFACE WATER Station Type Monitoring Sr No Station name Water Body Latitude Longitude NWMP Project code (River/Creek) Frequency Wainganga river at Ashti, Village- Ashti, Taluka- 1 11 River Wainganga River 19°10.643’ 79°47.140 ’ GEMS M Gondpipri, District-Chandrapur. Godavari river at Dhalegaon, Village- Dhalegaon, Taluka- 2 12 River Godavari River 19°13.524’ 76°21.854’ GEMS M Pathari, District- Parbhani. Bhima river at Takli near Karnataka border, Village- 3 28 River Bhima River 17°24.910’ 75°50.766 ’ GEMS M Takali, Taluka- South Solapur, District- Solapur. Krishna river at Krishna bridge, ( Krishna river at NH-4 4 36 River Krishna River 17°17.690’ 74°11.321’ GEMS M bridge ) Village- Karad, Taluka- Karad, District- Satara. Krishna river at Maighat, Village- Gawali gally, Taluka- 5 37 River Krishna River 16°51.710’ 74°33.459 ’ GEMS M Miraj, District- Sangli. Purna river at Dhupeshwar at U/s of Malkapur water 6 1913 River Purna River 21° 00' 77° 13' MINARS M works,Village- Malkapur,Taluka- Akola,District- Akola. Purna river at D/s of confluence of Morna and Purna, at 7 2155 River Andura Village, Village- Andura, Taluka- Balapur, District- Purna river 20°53.200’ 76°51.364’ MINARS M Akola. Pedhi river near road bridge at Dadhi- Pedhi village, 8 2695 River Village- Dadhi- Pedhi, Taluka- Bhatkuli, District- Pedhi river 20° 49.532’ 77° 33.783’ MINARS M Amravati. Morna river at D/s of Railway bridge, Village- Akola, 9 2675 River Morna river 20° 09.016’ 77° 33.622’ MINARS M Taluka- Akola, District- Akola. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Yavatmal District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Yavatmal District Carried out by MSME- Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) CGO Complex, Block ‘C’, Seminary Hills, Nagpur-440006 Phone: 0712-2510046, 2510352 Fax: 0712- 2511985 e-mail:[email protected] Web- msmedinagpur.gov.in 1 Contents S. Topic Page No. No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 5 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 5 1.2 Topography 5 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 6 1.4 Forest 7 1.5 Administrative set up 7 2. District at a glance 7-9 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District Yavatmal 10 3. Industrial Scenario of Yavatmal 11 3.1 Industry at a Glance 11 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 11-12 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In 13-18 The District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 19 3.5 Major Exportable Item 19 3.6 Growth Trend 1919 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 19 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 19 3.8.1 List of the units in Yavatmal & nearby Area 20 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 20 3.9 Service Enterprises 20 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 20 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 20 2 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 21 5. General issues raised by industry association during the course of 22 meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 23 3 4 Brief Industrial Profile of Yavatmal District 1. General Characteristics of the District: For the purpose of administrative conveyance, the district is divided into 16 Tahsils and 16 Panchayat Samities. -

Soil Fertility and Its Consequences for Vidarbha Region

ISSN(Online): 2319-8753 ISSN (Print): 2347-6710 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (A High Impact Factor, Monthly, Peer Reviewed Journal) Visit: www.ijirset.com Vol. 8, Issue 7, July 2019 Soil Fertility and Its Consequences for Vidarbha Region Wasupiyush A. 1*, Gawande Sagar M.2 M.E, Department of Civil Environmental Engineering, Anantrao Pawar COE & R, Pune, India. 1 Department of Civil Environmental Engineering, Anantrao Pawar COE & R, Pune, India. 2 ABSTRACT. India is the country where the 90 % population is depends on farming . the main income of source is their farms , but now a days development in technology is carried by farmers to earn maximum money . for that they use various types of pesticides various methods which gives them temporarily profit but that effects on human health , climatic change , water quality , soil quality , the use of pesticides makes land barrel .if the soil is rocky an on slope area that soil is infertile in nature because of runoff , in this paper we discuss about the eastern side of Maharashtra called vidarbha there is one town name yavatmal which have many issues of infertility of soil so what is the properties of that soil and which crops are taken in that particular area will discuss below . the max no of farmers suicide is from vidarbha because the rainfall is not sufficient and the type of soil found mainly black cotton soil the water holding capacity is poor that effects on directly the fertility of soil so we trying to found out the solution for that whole problem. -

(BILT) Chandrapur District, Maharashtra

Ph.D. SYNOPSIS Assessment of Hydrochemical Quality of Groundwater around Ballarpur Industries Limited (BILT) Chandrapur District, Maharashtra. ABSTRACT The groundwater is one of the most important criteria to ascertain its suitability for human beings and irrigation. As Ballarpur is an industrial area the present study focus on the effects of industrial waste water effluent on groundwater as well as on surface water occurring in Ballarpur area within the Chandrapur District of Maharashtra. The obtained results will be compared with World Health Organization (WHO) and Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) limits. Keywords: Groundwater, Physico-chemical Parameters, Seasonal variation, Hydrogeochemistry. INTRODUCTION As far as we know, earth is the only place in the entire universe where liquid water is found in considerable quantities. In general, it is believed that most of the earth’s water has been formed from oxygen and hydrogen released from rocks through volcanic activity. Earth is unique in having an atmosphere that traps the water vapour and a temperature range that keeps most of it in the Liquid form. Water is therefore a characteristic feature of earth. The sustainability of groundwater for drinking purpose is judged on the basis of pH, - +2 +2 -2 TDS, Total Hardness, Cl , Ca , Mg , Total alkalinity, Sulphate (SO4 ), Sodium, Potassium, etc. and sustainability of groundwater for irrigation purpose is judged on the basis of Sodium contents and Electrical Conductivity. STUDY AREA Chandrapur district is one of the eleven district of Vidarbha region of Maharashtra. It is bounded on south by Telangana state and east by Gadchiroli district on north by Bhandara, Gondia, Nagpur and Wardha district on by west by Yavatmal district. -

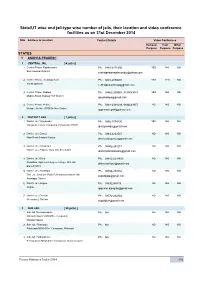

State/UT Wise and Jail-Type Wise Number of Jails, Their Location and Video Conference Facilities As on 31St December 2014

State/UT wise and jail-type wise number of jails, their location and video conference facilities as on 31st December 2014 SNo Address & Location Contact Details Video Conference Remand Trial Other Purpose Purpose Purpose STATES 1 ANDHRA PRADESH 1 CENTRAL JAIL [ 4 jail(s) ] 1 Central Prison, Rajahmundry Ph.: 0883-2471990 YES NO NO East Godavari District [email protected] 2 Central Prison, Visakhapatnam Ph.: 0891-2870601 YES YES NO Visakhapatnam [email protected] 3 Central Prison, Kadapa Ph.: 08562-200559, 9494633643 YES NO NO Madras Road, Kadapa YSR District [email protected] 4 Central Prison, Nellore Ph.: 0861-2331639, 9494633857 NO NO NO Mulapet, Nellore SPSR Nellore District [email protected] 2 DISTRICT JAIL [ 7 jail(s) ] 1 District Jail, Vijayawada Ph.: 0866-2574236 YES NO NO Vijaywada Taluka Compound Vijayawada-520003 [email protected] 2 District Jail, Guntur Ph.: 0863-2232547 NO NO NO Main Road Brodipet Guntur [email protected] 3 District Jail, Srikakulam Ph.: 08942-241251 NO NO NO District Jail, Ampolu, Gara (M), Srikakulam [email protected] 4 District Jail, Eluru Ph.: 08812-2244633 NO NO NO Kotadibba, Opp Govt. degree College, Dist Jail, [email protected] Eluru-534001 5 District Jail, Anantapur Ph.: 08554-257232 NO NO NO Dist. Jail Jantaloor (Post) Bukkarayasamudram (M) [email protected] Anantapur District 6 District Jail, Ongole Ph.: 08592280419 NO NO NO Ongole [email protected] 7 District Jail, Chittoor Ph.: 08572-242844 NO NO NO Greamspet, -

Yavatmal District at a Glance 1

YAVATMAL DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical Area 13519 sq. km Administrative Divisions : Taluka-16; Yavatmal, Ner, (As on 31/03/2011) Babhulgaon, Kalamb, Darwha, Digras, Pusad, Umarkhed, Mahagaon, Arni, Ghatanji, Kelapur, Ralegaon, Maragaon, Zhari- Zhamni and Wani Villages : 2108 Population (As per census 2011) : 27,75,457 Male 14,25,593 Female 13,49,864 Literacy 87.00% Sex Ratio 941 Average Annual Rainfall : 850 mm to 1150 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic unit : Three; Satpuda hill range, Plateau and Penganga and Wardha plain Major Drainage : Two; Wardha and Penganga, 3. LAND USE (2010-11) Forest Area : 2397 sq. km. Net Area Sown : 8746 sq. km. Cultivable Area : 10095 sq. km. 4. SOIL TYPE Three types of soils, Shallow coarse, Medium black and Deep black 5. PRINCIPAL CROPS (2010-11) Wheat : 160 sq. km. Cotton : 3867 sq. km. Jowar : 1092 sq. km. Soyabean : 1664 sq. km. Pulses : 1791 sq. km. 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (2010-11) Nos./Potential Created (ha) Dugwells : 40945 / 94807 Tubewells/Borewells : 805 / 1921 Tanks/Ponds : 71 / 10095 Other Minor Surface Sources : 7072 / 18360 Net Irrigated Area : 52193 7. GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS (As on 31/03/2011) Dugwells : 46 Piezometers : 19 8. GEOLOGY Recent : Alluvium Upper Cretaceous-Lower : Deccan Trap Basalt Eocene Cretaceous : Lameta Beds Upper Carboniferous - Permian : Gondwana Pre-Cambrian : Vindhyan /Pakhals/Penganga Beds Achaean : Granites/ Gneisses 9. HYDROGEOLOGY Water Bearing Formation : Aquifers belonging to Archean, Penganga Beds, Gondwana, Lameta and Deccan Traps Premonsoon Depth to Water : 1.00 to 16.60 m bgl Level (May 2011) Postmonsoon Depth to Water : 0.90 to 15.20 m bgl Level (Nov.