The Red Stockings of 1869 by Joseph S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

Rescatan a Elvira

Domingo 12 de Julio de 2015 aCCIÓN EXPRESO 5C A LFONSO ARAUJO BOJÓRQUEZ LOS RED STOCKINGS DE CINCINNATI l Club Cincinnati se estableció el 23 de junio de de acuerdo a aquella época, no Brooklyn y cuando el único am- vino la reacción de los Atlantics, 1866, en un despacho de abogados, en el que elabo- había guantes, el pitcher lanzaba payer, de nombre Charles Mills, que en forma sensacional hicie- raron los estatutos y designación de funcionarios, por debajo del brazo, la distancia cantó el pleybol, había gente por ron tres, para salir con el triunfo E desde donde lanzaba, era de solo todos lados y fácilmente rebasa- 8-7. Los gritos de la multitud se donde eligieron como presidente y lo convencieron de que formara 50 pies, la pelota un poco más ban los 12 mil afi cionados. Los podían escuchar por cuadras a a Alfred T. Gosharn. u n equ ipo profesion a l , busc a ndo chica que la actual y el bat era pitchers anunciados fueron Asa la redonda, escribió el corres- Después de jugar cuatro par- jugadores de otras ciudades, que cuadrado. Brainard, que había ganado to- ponsal del New York Sun. Los tidos en ese verano, se unieron se distinguieran en jugar buen Empezaron ganando con dos los juegos de Cincinnati y se jugadores de Cincinnati abor- en 1867 a la NABBP (National beisbol. Por lo pronto en 1868 mucha facilidad a equipos lo- enfrentaría a otro gran lanzador, daron rápidamente su ómnibus Association of Base Ball Players) llevaron a cabo 16 partidos per- cales y pronto llegó su fama a George Zettlein, que era un buen y dejaron el recinto, molestos e hicieron el acuerdo para jugar diendo solo ante los Nationals de otras ciudades, que los invita- bateador. -

By Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis

America’s Pastime: How Baseball Went from Hoboken to the World Series An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Kimberly Parkhurst Thesis Advisor Dr. Bruce Geelhoed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April 2020 Expected Date of Graduation July 2020 Abstract Baseball is known as “America’s Pastime.” Any sports aficionado can spout off facts about the National or American League based on who they support. It is much more difficult to talk about the early days of baseball. Baseball is one of the oldest sports in America, and the 1800s were especially crucial in creating and developing modern baseball. This paper looks at the first sixty years of baseball history, focusing especially on how the World Series came about in 1903 and was set as an annual event by 1905. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Carlos Rodriguez, a good personal friend, for loaning me his copy of Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, which got me interested in this early period of baseball history. I would like to thank Dr. Bruce Geelhoed for being my advisor in this process. His work, enthusiasm, and advice has been helpful throughout this entire process. I would also like to thank Dr. Geri Strecker for providing me a strong list of sources that served as a starting point for my research. Her knowledge and guidance were immeasurably helpful. I would next like to thank my friends for encouraging the work I do and supporting me. They listen when I share things that excite me about the topic and encourage me to work better. Finally, I would like to thank my family for pushing me to do my best in everything I do, whether academic or extracurricular. -

A Foul Ball in the Courtroom: the Baseball Spectator Injury As a Case of First Impression

Tulsa Law Review Volume 38 Issue 3 Torts and Sports: The Rights of the Injured Fan Spring 2003 A Foul Ball in the Courtroom: The Baseball Spectator Injury as a Case of First Impression J. Gordon Hylton Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation J. G. Hylton, A Foul Ball in the Courtroom: The Baseball Spectator Injury as a Case of First Impression, 38 Tulsa L. Rev. 485 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol38/iss3/3 This Legal Scholarship Symposia Articles is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hylton: A Foul Ball in the Courtroom: The Baseball Spectator Injury as a A FOUL BALL IN THE COURTROOM: THE BASEBALL SPECTATOR INJURY AS A CASE OF FIRST IMPRESSION J. Gordon Hylton* The sight of a fan injured by a foul ball is an unfortunate but regular feature of professional baseball games. Similarly, lawsuits by injured fans against the operators of ballparks have been a regular feature of litigation involving the national pastime.' While the general legal rule that spectators are considered to have assumed the risk of injury from foul balls has been reiterated over and over, injured plaintiffs have continued to sue in hope of establishing liability on the part of the park owner.2 Although the number of such lawsuits that culminated in published judicial reports is quite large, it is somewhat surprising that the first cases to reach the appellate court level did not do so until the early 1910s, nearly a half century after the beginnings of commercialized baseball.' * Professor of Law, Marquette University. -

Coaching Manual GAA Rounders Coaching Manual

GAA Rounders Cumann Lúthchleas Gael Coaching Manual GAA Rounders Coaching Manual Copyright: Cumann Cluiche Corr na hÉireann, CLG No re-use of content is permitted INDEX Chapter 1 Chapter 7 Why Coach 4Running 37 Chapter 2 Chapter 8 Throwing 6 Skills Practice 38 Overarm Throwing 6 (a) Throwing and Catching Exercises Underarm Throwing 7 (b) Running, Throwing and Catching Chapter 3 (c) Batting Practice Catching 8 Chapter 9 Chest High Ball 8 Batting 44 High Ball 8 Batting Order 44 Chapter 4 Strategy 44 Pitching 9 Chapter 10 Technique 9 Fielding 46 Strategy 9 Infield Play 46 Tips on Control 10 Outfield Play 46 Practices 11 Chapter 11 Chapter 5 Sliding 56 The Catcher 12 Chapter 12 Characteristics 12 Mini-Rounders 58 Technique 12 Rules 58 Squat Position 16 Aim of Mini-Rounders 59 Chair Position 18 Glossary 64 Chapter 6 Hitting 19 Choose the right Bat 19 Hitting Area 19 The Grip 20 Bat Position 22 The Stance 24 The Stride 27 The Swing 27 Bunting 33 3 GAA Rounders Coaching Manual CHAPTER 1 – Why Coach? A team and a coach are a unit. One does not function well without the other. A happy, united and sincere approach to learning the game is essential, and a good coach can nurture this. A coach is also responsible for motivating a team and ensuring it goes to play with the right attitude. The skills and techniques we impart to our young players and beginners will be their foundation as older and more seasoned players. Why do we coach Rounders? In answer there are several reasons. -

A National Tradition

Baseball A National Tradition. by Phyllis McIntosh. “As American as baseball and apple pie” is a phrase Americans use to describe any ultimate symbol of life and culture in the United States. Baseball, long dubbed the national pastime, is such a symbol. It is first and foremost a beloved game played at some level in virtually every American town, on dusty sandlots and in gleaming billion-dollar stadiums. But it is also a cultural phenom- enon that has provided a host of colorful characters and cherished traditions. Most Americans can sing at least a few lines of the song “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Generations of children have collected baseball cards with players’ pictures and statistics, the most valuable of which are now worth several million dollars. More than any other sport, baseball has reflected the best and worst of American society. Today, it also mirrors the nation’s increasing diversity, as countries that have embraced America’s favorite sport now send some of their best players to compete in the “big leagues” in the United States. Baseball is played on a Baseball’s Origins: after hitting a ball with a stick. Imported diamond-shaped field, a to the New World, these games evolved configuration set by the rules Truth and Tall Tale. for the game that were into American baseball. established in 1845. In the early days of baseball, it seemed Just a few years ago, a researcher dis- fitting that the national pastime had origi- covered what is believed to be the first nated on home soil. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

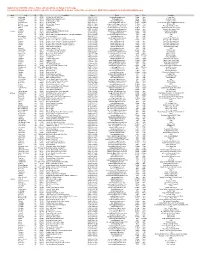

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

Wildcats' Thomas Does It

SATURDAY, MARCH 27, 2021 • SECTION B Editor: Ryan Finley / [email protected] WILDCATS’ THOMAS DOES IT ALL UA needs stat-sheet-stuffing senior to step up in Saturday’s Sweet 16 game vs. Texas A&M PHOTO BY KELLY PRESNELL / ARIZONA DAILY STAR Hansen: Game a battle of Aggies must contend with Familiar faces joining SPORTS SECTION program-building coaches Wildcats’ sensational Sam new ones in Sweet 16 field STARTS ON B9 Arizona’s Barnes, A&M’s Blair crossed Four-year captain Thomas baffles opponents Early upsets have changed the calculus in Check out the Star’s UA paths on their way to the top. B2 with versaility, defensive tenacity. B6-7 a tournament that’s typically chalky. B8 football and softball coverage, and read up on Saturday’s NCAATournament games. B2 NCAA EXTRA SATURDAY, MARCH 27,2021 / ARIZONA DAILYSTAR RESTORATION SPECIALISTS BARNES, BLAIR MEET IN SATURDAY’S SWEET 16 he master builders of the Calipari. Arizona won the WNIT title You get the best shot from T women’s Sweet 16 are Barnes and Blair have every- a day later, Barnes went on to be the super-powers like A&M. Arizona’s Adia Barnes and thing and nothing in common. the Pac-10’s 1998 Player of the How good are the No. 2-seeded Texas A&M’s Gary Blair. They are Barnes is 43. Blair is 75. Barnes Year and the leading scorer in Aggies? They start three Mc- restoration specialists, no job too was a pro basketball player. Arizona history. Blair, then, 50, Donald’s All-Americans: Aaliyah big, too messy or too tiresome. -

The Flying Scottsman" Tossups

"The Flying Scottsman" Tossups 1. Born in 1784 in Minden, by the age of 34 he had compiled a catalog including 50,000 stars. Among his most siginificant innovations was the development of a series of functions for use in astronomical calculations that now bear hisname. For ten pOints, who was this Prussian astronomer, who in 1838, while observing the star 61 Cygni became the first man to successfully measure the parallax of a star? ANS: Friedrich Bessell 2. Nicknamed "Bunny," five years after graduating from Princeton, he became editor of "Vanity Fair" magazine. A writer of broad interests, his books include the novel "I Thought of Daisy", the sociological study "Red, Black, Blond, and Olive", and a study of symbolism, "Axel's Castle". For ten pOints, name this man who translated the Dead Sea Scrolls and examined European radicalism in "To the Finland Station." ANS: Edmund Wilson 3. The son of a fireman, he attended night school in his late teens to learn to read so that he could study the work of James Watt. The work of Richard Trevithick served as the building blocks for this man's accomplishments, much as the work of John Fitch was followed by that of Robert Fulton. For ten pOints, who was this inventor, who in 1830 opened between Liverpool and Manchester the first railroad using steam powered locomotives? ANS: George Stephenson 4. Troubled with chronic poor health throughout his life, he habitually worked while staying in bed. A devout Catholic due to his Jesuit education, upon hearing of the condemnation of Galileo by the church, he abandoned a book supporting the Copernican system. -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible.