Harappan Settlement Pattern on the Desert Margin with Special Reference to Hanumangarh District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Level Sustainable Livestock Production Index: Tool for Livestock Development Planning in Rajasthan

Ind. Jn. of Agri. Eco. Vol.67, No.2, April.-June, 2012 ARTICLES District Level Sustainable Livestock Production Index: Tool for Livestock Development Planning in Rajasthan Prem Chand and Smita Sirohi* I INTRODUCTION Since the past two decades, the concept of sustainability has increasingly occupied the centre stage for the development of the agriculture and allied sectors. With the manifestation of stagnating or declining productivity levels, widening regional disparities and the emergence of environmental externalities, the concerns emerged that development process should be sustainable, i.e., it should be environmentally non-degrading, technically appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable (FAO, 1991). Before targeting the policy interventions to maintain/enhance the sustainability of a crop or livestock production system, it is imperative to examine whether or not certain necessary conditions essential for sustainable development are present in a given region or ecosystem. The major approaches used in the literature to assess the sustainability of a biological production system in a particular region include, estimation of total factor productivity (Ehui and Spencer, 1990; Rosegrant and Evenson, 1995; Kumar and Mittal, 2006), computation of composite indices covering varied dimensions of sustainability (Saleth and Swaminathan, 1992; Yadav and Rai, 2001; Calker et al., 2004; Sen and Hatai, 2007; Singh and Hiremath, 2010) and Response-Inducing Sustainability Evaluation (RISE) (Hani et al., 2003). While each of these techniques has its own utility, the indexing approach provides a simple practical tool for indicating a set of projects and policies that can be implemented to address the problem areas that impede sustainability. In India, the empirical application of indexing approach has been made in the context of livelihood security, focusing on the ecological and economic dimensions related to crop production. -

Rajasthan List.Pdf

Interview List for Selection of Appointment of Notaries in the State of Rajasthan Date Of Area Of S.No Name Category Father's Name Address Enrol. No. & Date App'n Practice Village Lodipura Post Kamal Kumar Sawai Madho Lal R/2917/2003 1 Obc 01.05.18 Khatupura ,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.28.12.03 Madhopur,Rajasthan Village Sukhwas Post Allapur Chhotu Lal Sawai Laddu Lal R/1600/2004 2 Obc 01.05.18 Tehsil Khandar,Sawai Gurjar Madhopur Gurjar Dt.02.10.04 Madhopur,Rajasthan Sindhu Farm Villahe Bilwadi Ram Karan R/910/2007 3 Obc 01.05.18 Shahpura Suraj Mal Tehsil Sindhu Dt.22.04.07 Viratnagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Opposite 5-Kha H.B.C. Sanjay Nagar Bhatta Basti R/1404/2004 4 Abdul Kayam Gen 02.05.18 Jaipur Bafati Khan Shastri Dt.02.10.04 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Jajoria Bhawan Village- Parveen Kumar Ram Gopal Keshopura Post- Vaishali R/857/2008 5 Sc 04.05.18 Jaipur Jajoria Jajoria Nagar Ajmer Dt.28.06.08 Road,Jaipur,Rajasthan Kailash Vakil Colony Court Road Devendra R/3850/2007 6 Obc 08.05.18 Mandalgarh Chandra Mandalgarh,Bhilwara,Rajast Kumar Tamboli Dt.16.12.07 Tamboli han Bhagwan Sahya Ward No 17 Viratnagar R/153/1996 7 Mamraj Saini Obc 03.05.18 Viratnagar Saini ,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.09.03.96 156 Luharo Ka Mohalla R/100/1997 8 Anwar Ahmed Gen 04.05.18 Jaipur Bashir Ahmed Sambhar Dt.31.01.97 Lake,Jaipur,Rajasthan B-1048-49 Sanjay Nagar Mohammad Near 17 No Bus Stand Bhatta R/1812/2005 9 Obc 04.05.18 Jaipur Abrar Hussain Salim Basti Shastri Dt.01.10.05 Nagar,Jaipur,Rajasthan Vill Bislan Post Suratpura R/651/2008 10 Vijay Singh Obc 04.05.18 Rajgarh Dayanand Teh Dt.05.04.08 Rajgarh,Churu,Rajasthan Late Devki Plot No-411 Tara Nagar-A R/41/2002 11 Rajesh Sharma Gen 05.05.18 Jaipur Nandan Jhotwara,Jaipur,Rajasthan Dt.12.01.02 Sharma Opp Bus Stand Near Hanuman Ji Temple Ramanand Hanumangar Rameshwar Lal R/29/2002 12 Gen 05.05.18 Hanumangarh Sharma h Sharma Dt.17.01.02 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an Ward No 23 New Abadi Street No 17 Fatehgarh Hanumangar Gangabishan R/3511/2010 13 Om Prakash Obc 07.05.18 Moad Hanumangarh h Bishnoi Dt.14.08.10 Town,Hanumangarh,Rajasth an P.No. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Hanumangarh District

lR;eso t;rs lR;eso t;rs Brief Industrial Profile of Hanumangarh District Carried out by MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone : 0141-2213099 ,2212098,2215847 Fax: 0141-2210533 e-mail: [email protected] Web : www.msmedijaipur.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 4 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 5 1.2 Topography 5 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5-6 1.4 Forest 6 1.5 Administrative set up 7 2. District at a glance 7-11 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District -------- 11 3. Industrial Scenario Of --------- 11 3.1 Industry at a Glance 12 3.2 Year Wise Trend Of Units Registered 12 3.3 Details Of Existing Micro & Small Enterprises & Artisan Units In 13 The District 3.4 Large Scale Industries / Public Sector undertakings 13 3.5 Major Exportable Item 13 3.6 Growth Trend 14 3.7 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 14 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 14 3.8.1 List of the units in ------ & near by Area 14 3.8.2 Major Exportable Item 14 3.9 Service Enterprises 14 3.9.1 Potentials areas for service industry 14 3.10 Potential for new MSMEs 14-15 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprise 15 4.1 Detail Of Major Clusters 15 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 15 4.1.2 Service Sector 15 4.2 Details of Identified cluster 16 4.2.1 Leather Footwear 16 4.2.2 Plats of Paris 17 5. -

Regional Study of Variation in Cropping and Irrigation Intensity in Rajasthan State, India

Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726)(2017), 5(4): 98-105 98 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V5N4-art1314 REGIONAL STUDY OF VARIATION IN CROPPING AND IRRIGATION INTENSITY IN RAJASTHAN STATE, INDIA. ESTUDIO REGIONAL DE LA VARIACION DE LA INTENSIDAD DE IRRIGACION Y AGRICULTURA EN EL ESTADO DE RAJASTAN, INDIA. Arjun Lal Meena1 and Priyanka Bisht2 1- Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected] 2- Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Jai Narain Vyas University, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India. Email: [email protected] Submitted: 05th November 2017; Accepted: 12th December, 2017. ABSTRACT Agriculture is the primary activity which directly or indirectly influences the other activities. It plays a vital role to achieve the self-sufficiency in each sector of economy. Irrigation plays a crucial role in farming for those areas suffering from irregular pattern of rainfall. Rajasthan is the state of India which usually faces the drought condition as the monsoon gets fall. The farming in this state totally depends on the irrigation. This paper includes the district-wise distribution of cropping intensity and irrigation intensity including the comparison of 2013-2014 with the year 2006- 2007. Key words: Irrigation Intensity, Cropping Intensity, Net Area, Gross Area. RESUMEN La agricultura es una actividad primeria la cual está directa o indirectamente relacionada con otras actividades. Esta tiene un rol vital en la autosustentabilidad en cada sector de la economía. La irrigación tiene un rol importante en las granjas de Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, (ISSN: 0719-3726)(2017), 5(4): 98-105 99 http://dx.doi.org/10.7770/safer-V5N4-art1314 estas áreas y tiene un patrón irregular debido a las lluvias. -

A CASE STUDY of SIKAR, RAJASTHAN Manisha

Journal of Global Resources Volume 4 (01) January 2018 Page 133-137 ISSN: 2395-3160 (Print), 2455-2445 (Online) 20 STRATEGIC PLANS FOR INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT AND ITS POTENTIAL: A CASE STUDY OF SIKAR, RAJASTHAN Manisha Sharma 1and M. A. Khan 2 1 Head, Dept. of Geography. B.D. Todi College, Lachhmangarh (Sikar), India 2Deputy Director, Department of Minority Affairs, GoR, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India Abstract: Industrial Potential means anything that may be a possibility; potentially and existing in possibility, not in actuality and being potent. Industrial or economic potential is determined by the quantity of labor resources and the quality of their vocational training by the volume of production capacities of Industrial and construction organizations, by the production capacities of agriculture, by the extent of transportation arteries, by the development of sectors in the non-production sphere by advances in science and technology and by the resources of explored mineral deposits. Resources have the most vital role in the development of a region. The main resources of study area which have great significance for industrial development are minerals, agriculture and livestock. Water and electricity provides basis for Industrial development. However, the area has good potential for agro based, mineral based and livestock based industries. As Sikar enjoys the benefits of surplus agricultural production and large number of livestock, it would be worthwhile to propose few agro based and livestock industrial units. Limestone is also being exploited so, there is scope of cement and others industries. This paper describes a strategic plan for development of Industries and its potential in Sikar district. -

Sarasvati Civilization, Script and Veda Culture Continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution

Sarasvati Civilization, script and Veda culture continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution The monograph is presented in the following sections: Introduction including Abstract Section 1. Tantra yukti deciphers Indus Script Section 2. Momentous discovery of Soma samsthā yāga on Vedic River Sarasvati Basin Section 3. Binjor seal Section 4. Bhāratīya itihāsa, Indus Script hypertexts signify metalwork wealth-creation by Nāga-s in paṭṭaḍa ‘smithy’ = phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office, keeper of all accounts, registers’ Section 5. Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan is an Indus Script hypertext to signify Superintendent of phaḍa ‘metala manufactory’ Section 6. Note on the cobra hoods of Daimabad chariot Section 7 Note on Mohenjo-daro seal m0304: phaḍā ‘metals manufactory’ Section 8. Conclusion Introduction The locus of Veda culture and Sarasvati Civilization is framed by the Himalayan ranges and the Indian Ocean. 1 The Himalayan range stretches from Hanoi, Vietnam to Teheran, Iran and defines the Ancient Maritime Tin Route of the Indian Ocean – āsetu himācalam, ‘from the Setu to Himalayaś. Over several millennia, the Great Water Tower of frozen glacial waters nurtures over 3 billion people. The rnge is still growing, is dynamic because of plate tectonics of Indian plate juttng into and pushing up the Eurasian plate. This dynamic explains river migrations and consequent desiccation of the Vedic River Sarasvati in northwestern Bhāratam. Intermediation of the maritime tin trade through the Indian Ocean and waterways of Rivers Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, Ganga, Sarasvati, Sindhu, Persian Gulf, Tigris-Euphrates, the Mediterranean is done by ancient Meluhha (mleccha) artisans and traders, the Bhāratam Janam celebrated by R̥ ṣi Viśvāmitra in R̥ gveda (RV 3.53.12). -

Research Article IMPACT of FORMAL CREDIT on AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT in the RAJASTHAN

International Journal of Agriculture Sciences ISSN: 0975-3710&E-ISSN: 0975-9107, Volume 9, Issue 5, 2017, pp.-3763-3766. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217 Research Article IMPACT OF FORMAL CREDIT ON AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT IN THE RAJASTHAN KUMAWAT RAJU1*, SINGH N.K.1 AND PRAMENDRA2* 1Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture, Swami Keshwanand Rajasthan Agricultural University, Bikaner, 334006, Rajasthan 2Department of Agricultural Economics & Management, RCA, Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology, Udaipur, 313001, Rajasthan *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: January 09, 2017; Revised: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 17, 2017; Published: January 30, 2017 Abstract- The present study was conducted to analyse the impact of agricultural credit on agricultural development and constraints in advancing the agricultural credit. The study was conducted in the district of Bikaner region viz., Sriganganagar, Hanumangarh, Bikaner and Churu district. A lead bank of each selected district was selected purposively for collection of secondary and primary data in respect of agricultural loan supplied to the farmers. A sample of 30 farmers was drawn as borrower farmers from each selected district by probability proportion to the number of borrower farmers. The increasing trend was observed in the value of net worth with increase in farm size on both borrower and non-borrower farmers of the study area. At overall level about 47 to 50 per cent net worth value was higher on borrower farmers than the non-borrower farmers. The value of current assets was ranged from 1.81 to 3.82 on borrower farmers in comparison to non-borrower farmers 1.02 to 2.90. -

District Census Handbook, Churu, Rajasthan and Ajmer

CENSUS, 195 1 RAJASTHAN AND AJMER DISTRICT CERUS' ,HANDBOOK CHURU PART .-GENERAL DESCRIPTION AND CENSUS TABLES By Pt. YAMUNA LAL DASHORA, B.A., LL.B., Superintendent of Censl1s Operations, Rajasthan and Aimer. JODHPUR: P.RINTED AT THE GOVE]1};llENT PRESS 1956 1f.R:EFAcE, .... ,:, . - , 'The "CensuA Reports' ill' .qlq.en -·times :were printed one for the whole Province. of Ra.j putana and.another for A-jIl1:er-:Merwara._"Soin~ of the Principal 8tates now merged in Rajasthan published 'their own reports. This time the -State Census H eports have been published in the following volumes:- 1. Part I A .. Report. 2. Part 1--B .. ~ubsidiary Tables and District Index of Non-Agricultural Occupations. 3. Part I -C .. Appendices. 4. Part U-A .. r::eneral Population Tables, Household and Age Sample Tables, Social and Cultural Tables, Table E Summary Figures by Administrative Units, and Local 'KA' Infirmities. 5. Part II-B .. Economic Tables. They contain statistics down to the district level The idea of preparing the District Census Handbook separately for each district was put forward .by' Shri R. A. GopaJaswami. I. C. R., Registrar General. India, and ex-officio Census' Commissioner of' India, as part of a plan intended to secu~e an effective, method of preserving the census records prepared for areas below the qistrict level. 'He proposed that all the district, census tables and census abstracts prepared during the process of sorting and cOinpilatiori should be bound together in a single manuscript volume, called the District Census Handbook, and suggested to the State Governments that the Handbook (with or without the addition of other useful information relating to the district) should be printed and pub lished at their own cost in the same manner as the village statistics in the past. -

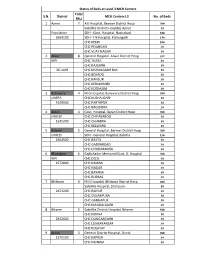

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N

Status of Beds at Level 3 MCH Centers Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 1 Ajmer 7 A K Hospital, Beawer District Hosp 300 Satellite District Hospital, Ajmer 30 Population SDH - Govt. Hospital, Nasirabad 100 2664100 SDH- Y N Hospital, Kishangarh 150 CHC KEKRI 100 CHC PISANGAN 30 CHC VIJAY NAGAR 30 2 Alwar 8 General Hospital, Alwar District Hosp 332 NIPI CHC TIJARA 30 CHC RAJGARH 50 36 LAKH CHC KISHANGARH BAS 50 CHC BEHROD 50 CHC BANSUR 30 CHC KERLIMANDI 30 CHC KOTKASIM 30 3 Banswara 4 M G Hospital, Banswara District Hosp 300 UNFPA CHC KUSHALGARH 50 1629900 CHC PARTAPUR 30 CHC BAGIDORA 30 4 Baran 4 Govt. Hospital, Baran District Hosp 300 UNICEF CHC CHIPABAROD 30 1245200 CHC CHHABRA 50 CHC KELWARA 30 5 Barmer 5 General Hospital, Barmer District Hosp 200 UNICEF SDH - General Hospital, Balotra 150 2404500 CHC BAYTU 30 CHC GADRAROAD 30 CHC DHORIMANNA 30 6 Bharatpur 6 RajBahadur Memorial Govt. D. Hospital 300 NIPI CHC DEEG 50 2572800 CHC KAMAN 30 CHC NAGAR 30 CHC BAYANA 50 CHC RUPBAS 30 7 Bhilwara 6 M G Hospital, Bhilwara District Hosp 400 Satellite Hospital, Shahpura 50 2453200 CHC RAIPUR 30 CHC GULABPURA 50 CHC GANGAPUR 50 CHC MANDALGARH 50 8 Bikaner 5 Satellite District Hospital, Bikaner 100 CHC NOKHA 50 2322600 CHC DUNGARGARH 30 CHC LUNKARANSAR 30 CHC KOLAYAT 30 9 Bundi 3 General District Hospital, Bundi 300 1170100 CHC KAPREN 30 CHC NAINWA 50 Total S.N. District MCH Centers L3 No. of Beds FRU 10 Chittorgarh 5 District Hospital, Chittorgarh 300 1629900 CHC BEGUN 50 CHC KAPASAN 50 CHC BADISADRI 50 CHC NIMBAHERA 100 11 Churu 5 D B Hospital, Churu District Hospital 225 2059300 SDH - S R J Hospital, Ratangarh 100 SDH - S B Hospital, Sujangarh 100 CHC RAJGARH 50 CHC SARDARSHAHAR 75 12 Dausa 3 District Hospital, Dausa 150 NIPI CHC LALSOT 30 1606100 CHC MAHUWA 30 13 Dholpur 4 Sadar District Hospital, Dholpur 300 1196300 CHC RAJAKHERA 30 CHC BARI 50 CHC BASERI 30 14 Dungarpur 4 General District Hospital, Dungarpur 300 UNICEF SDH - Govt. -

Final Population Figures, Series-18, Rajasthan

PAPER 1 OF 1982 CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 18 RAJASTHAN fINAL POPULATION FIGU~ES (TOTAL POPULATION, SCHEDULED CASTE POPULATION AND .sCHEDULED TRIBE POPULATION) I. C. SRIVASTAVA ·1)f the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Rajasthan INTRODUCfION The final figures of total population, scheduled caste and scheduled tribe population of Rajasthan Stat~ are now ready for release at State/District/Town and Tehsil levels. This Primary Census Abs tract, as it is called, as against the provisional figures contained in our three publications viz. Paper I, fFacts & Figures' and Supplement to Paper-I has been prepared through manual tabulation by over 1400 census officials including Tabulators, Checkers and Supervisors whose constant and sustained efforts spread over twelve months enabled the Directorate to complete the work as per the schedule prescribed at the national level. As it will take a few months more to publish the final population figures at the viJ1age as well as ward levels in towns in the form of District Census Handbooks, it is hoped, this paper will meet the most essential and immediate demands of various Government departments, autonomous bodies, Cor porations, Universities and rtsearch institutions in relation to salient popUlation statistics of the State. In respect of 11 cities with One lac or more population, it has also been possible to present ~the data by municipal wards as shown in Annexure. With compliments from Director of Census Operations, Rajasthan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION (iii) Total Population, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribt' Population by Districts, 1981 Total Schedu1ed Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population. ( vi) 1. Ganganagar District 1 2. -

Kalibangan (Pre – Harappan Settlement)

Kalibangan (Pre – Harappan Settlement) Dr. Dilip Kumar Assistant Professor (Guest) Dept. of Ancient Indian History & Archaeology, Patna University, Patna Paper – CC-XI, Sem. – III Kalibangan is a town located at 29.47°N 74.13°E on the left or southern banks of the Ghaggar (Ghaggar - Hakra River) in Rajasthan. The Kalibangan pre-historic site was discovered by Luigi Pio Tessitori, an Italian Indologists (1887–1919). He was doing some research in ancient Indian texts and was surprised by the character of ruins in that area. He sought help from Sir John Marshall of the Archaeological Survey of India. At that time the ASI was conducting excavations at Harappa, but they were unaware of the significance of the ruins. In fact, Tessitori was the first person to recognize that the ruins were 'Prehistoric' and pre-Mauryan. Luigi Pio Tessitori also pointed out the nature of the culture, but at that time it was not possible to guess that the ruins of Kalibangan lay within the Indus Valley Civilization. He died five years before the Harappan culture was formally recognized. After India's independence, both the major Harappan cities together with the Indus became a part of Pakistan and Indian archaeologists were compelled to intensify the search for Harappan sites in India. Amlanand Ghosh (Ex. Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, or ASI) was the first person to recognise this site as Harappan and marked it out for excavations. Under the leadership of B. B. Lal (then Director General, ASI), Balkrishna (B.K.) Thapar, M. D. Khare, K. M. Shrivastava and S. -

Indus Valley Civilization

Indus Valley Civilization From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Extent of the Indus Valley Civilization Bronze Age This box: • view • talk • edit ↑ Chalcolithic Near East (3300-1200 BCE) Caucasus, Anatolia, Levant, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Elam, Jiroft Bronze Age collapse Europe (3200-600 BCE) Aegean (Minoan) Caucasus Basarabi culture Coț ofeni culture Pecica culture Otomani culture Wietenberg culture Catacomb culture Srubna culture Beaker culture Unetice culture Tumulus culture Urnfield culture Hallstatt culture Atlantic Bronze Age Bronze Age Britain Nordic Bronze Age Italian Bronze Age Indian Subcon tinent (3300- 1200 BCE) China (3000- 700 BCE) Korea (800- 300 BCE) arsenic al bronze writing , literatu re sword, chariot ↓ Iron Age The Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) that was located in the northwestern region[1] of the Indian subcontinent,[2][3] consisting of what is now mainly modern-day Pakistan and northwest India. Flourishing around the Indus River basin, the civilization[n 1] primarily centred along the Indus and the Punjab region, extending into the Ghaggar- Hakra River valley[7] and the Ganges-Yamuna Doab.[8][9] Geographically, the civilization was spread over an area of some 1,260,000 km², making it the largest ancient civilization in the world. The Indus Valley is one of the world's earliest urban civilizations, along with its contemporaries, Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. At its peak, the Indus Civilization may have had a population of well over five million. Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft (carneol products, seal carving) and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin.