Desert Legends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Fort Bowie U.S

National Park Service Fort Bowie U.S. Department of the Interior Fort Bowie National Historic Site The Chiricahua Apaches Introduction The origin of the name "Apache" probably stems from the Zuni "apachu". Apaches in fact referred to themselves with variants of "nde", simply meaning "the people". By 1850, Apache culture was a blend of influences from the peoples of the Great Plains, Great Basin, and the Southwest, particularly the Pueblos, and as time progressed—Spanish, Mexican, and the recently arriving American settler. The Apache Tribes Chiricahua speak an Athabaskan language, relating Geronimo was a member of the Bedonkohe, who them to tribes of western Canada. Migration from were closely related to the Chihenne (sometimes this region brought them to the southern plains by referred to as the Mimbres); famous leaders of the 1300, and into areas of the present-day American band included Mangas Coloradas and Victorio. Southwest and northwestern Mexico by 1500. This The Nehdni primarily dwelled in northern migration coincided with a northward thrust of Mexico under the leadership of Tuh. the Spanish into the Rio Grande and San Pedro Valleys. Cochise was a Chokonen Chiricahua leader who rose to leadership around 1856. The Chockonen Chiricahuas of southern Arizona and New primarily resided in the area of Apache Pass and Mexico were further subdivided into four bands: the Dragoon Mountains to the west. Bedonkohe, Chokonen, Chihenne, and Nehdni. Their total population ranged from 1,000 to 1,500 people. Organization and Apache population was thinly spread, scattered of Apache government and was the position that Family Life into small groups across large territories, tribal chiefs such as Cochise held. -

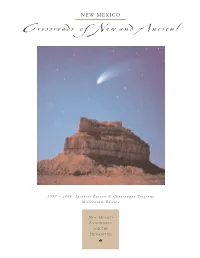

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

The Cretaceous System in Central Sierra County, New Mexico

The Cretaceous System in central Sierra County, New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, New Mexico Museum of Natural History, Albuquerque, NM 87104, [email protected] W. John Nelson, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, [email protected] Karl Krainer, Institute of Geology, Innsbruck University, Innsbruck, A-6020 Austria, [email protected] Scott D. Elrick, Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign, IL 61820, [email protected] Abstract (part of the Dakota Formation, Campana (Fig. 1). This is the most extensive outcrop Member of the Tres Hermanos Formation, area of Cretaceous rocks in southern New Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rocks are Flying Eagle Canyon Formation, Ash Canyon Mexico, and the exposed Cretaceous sec- Formation, and the entire McRae Group). A exposed in central Sierra County, southern tion is very thick, at about 2.5 km. First comprehensive understanding of the Cretaceous New Mexico, in the Fra Cristobal Mountains, recognized in 1860, these Cretaceous Caballo Mountains and in the topographically strata in Sierra County allows a more detailed inter- pretation of local geologic events in the context strata have been the subject of diverse, but low Cutter sag between the two ranges. The ~2.5 generally restricted, studies for more than km thick Cretaceous section is assigned to the of broad, transgressive-regressive (T-R) cycles of 150 years. (ascending order) Dakota Formation (locally deposition in the Western Interior Seaway, and includes the Oak Canyon [?] and Paguate also in terms of Laramide orogenic -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Fort Craig's 150Th Anniversary Commemoration, 2004

1854-1885 Craig Fort Bureau of Land Management Land of Bureau Interior the of Department U.S. The New Buffalo Soldiers, from Shadow Hills, California, reenactment at Fort Craig's 150th Anniversary commemoration, 2004. Bureau of Land Management Socorro Field Office 901 S. Highway 85 Socorro, NM 87801 575/835-0412 or www.blm.gov/new-mexico BLM/NM/GI-06-16-1330 TIMELINE including the San Miguel Mission at Pilabó, present day Socorro. After 1540 Coronado expedition; Area inhabited by Piro and Apache 1598 Spanish colonial era begins the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, many of the Piro moved south to the El Paso, 1821 Mexico wins independence from Spain Before Texas area with the Spanish, probably against their will. Others scattered 1845 Texas annexed by the United States and joined other Pueblos, leaving the Apache in control of the region. 1846 New Mexico invaded by U.S. General Stephen Watts Kearney; Territorial period begins The Spanish returned in 1692 but did not resettle the central Rio Grande 1849 Garrison established in Socorro 1849 –1851 hoto courtesyhoto of the National Archives Fort Craig P valley for a century. 1851 Fort Conrad activated 1851–1854 Fort Craig lies in south central New Mexico on the Rio Grande, 1854 Fort Craig activated El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, or The Royal Road of the Interior, was with the rugged San Mateo Mountains to the west and a brooding the lifeline that connected Mexico City with Ohkay Owingeh, (just north volcanic mesa punctuating the desolate Jornada del Muerto to the east. of Santa Fe). -

Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett

Library of Congress Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett Redfield Georgia B. FEB 15 1937 [?] 2/11/37 512 words Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett Given In An Interview. Feb. 9-1937 “As an ‘old-timer’-as you say-I will be glad to tell you anything you would like to hear of my life in our Sunshine State-New Mexico”; said Elizabeth Garrett in an appreciated interview graciously granted this writer. Appreciated because undue publicity of her splendid achievuments and of her private life, is avoided by this famous but unspoiled musician and composer. “My father, Pat Garrett came to Fort Sumner New Mexico in 1878. He and my mother, who was Polinari Gutierez Gutiernez , were married in Fort Sumner. “I”Was born at Eagle Creek, up above the Ruidoso in the White Mountain country. “We moved to Roswell (five miles east) while I was yet an infant. I have never been back to my birthplace but believe a lodge has been built on our old mountain home site. “You ask what I think of the Elizabeth Garrett bill presented at this session of the legislature? To grant me a monthly payment during my lifetime for what I have accomplished of the State Song, I think was a beautiful tho'ught. Early Life of Elizabeth Garrett http://www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh1.19181508 Library of Congress “I owe appreciation and thanks to New Mexico people and particulary to Grace T. Bear and to the “Club o' Ten” as the originators of the idea. If this bill is passed New Mexico will be the first state that has given such evidence of appreciation (in such a distinctive way) to a composer & autho'r of a State Song. -

Klondike Basin--Late Laramide Depocenter in Southern New Mexico

KlondikeBasin-late Laramide depocenter insouthern New Mexico by TimothyF. Lawton and Busse// E. Clemons, Departmentof Earth Sciences, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003 Abstract It was deposited in alluvial-fan, fluvial, Basinis thusa memberof a groupof late and plava environments adiacent to the Laramidebasins developed in and ad- The Klondike Basindefined in this pa- Lund uftift. Conglomerates'inthe lower iacentto theforeland in Paleogenetime. per occurs mostly in the subsurfaceof part of the section were derived from southwestem New Mexico, north of the nearby sedimentary shata of the uplift; Introduction Cedar Mountain Range and southwest volcanic arenites in the middle and up- Mexico and of Deming. The basin is asymmetric, per part of the section were derived from In southwestern New thickening from a northern zero edge in older volcanic rocks, including the Hi- southeastern Arizona, the Laramide the vicinity of Interstate 10 to a maxi- dalgo Formation, lying to the west and orogeny created a broad belt of north- mum preservedthickness of2,750 ft (840 northwest, and possibly to the north as west-trending faults and folds during the m) of sedimentary strata about 3 mi (5 well. approximate time span of 75-55 Ma (Da- km) north of the sbuthembasin margin. The age of the Lobo Formation and vis, 1979;Drewes, 1988).In contrast with The southem basin margin is a reverse development of the Klondike Basin are Laramide deformation of the Rocky fault or fault complex that bounds the bracketedas early to middle Eocene.The Mountain region, extensivevolcanism ac- Laramide Luna uplift, alsodefined here. asdasts Hidalgo Formation, which occurs companied shortening in Arizona and New The uplift consists of Paleozoic strata in the Lobo, has an upper fission-track has been inter- overlain unconformably by mid-Tertiary ageof 54.9+2.7Ma (Marvinetal.,1978\. -

Issue No. 87: April 2011

ZIM CSWR OVII ; F 791 IC7x CII nOl87 ~r0111Ca oe Nuevo Mexico ~ Published since 1976 - The Official Publication of the Historical Society ofNew Mexico OJ April 2011 Issue Nurrrbez- 87 Lincoln County - Full of History According to the New Mexico Blue county seat was in the now historic Book, Lincoln County was . at one time. district of the village of Lincoln where the the largest county in New Mexico. Lincoln County War and Billy the Kid's Created on January 16, 1869 and named role in the conflict are a major part of in honor of Presid ent Abraham Lincoln. their history. the area in the south central part of the Not only is Lincoln County known as state. has had more than its share of "Billy the Kid Country" it also is the site of "exciting" (then and now) events. The first Fort Stanton which has a lonq and colorful history beqinntns in the days before the CivilWar. They have a museum and visitors center. To learn more about Fort Stanton. see recently published book by Lynda Sanchez. Fort Stanton: An Illustrated History. Legacy of Honor, Tradition ofHealing. Capitan qained fame with Smokey Bear when a cub was found on May 19, 1950 after a fire in the Lincoln National Signs in Lincoln New Mexico (Photograph by Carlee n Lazzell, April 28 . 2010) Forest. Shortly thereafter Smokey was the Smokey Bear Historical Park where A few miles to the northeast of taken to the National Zoo in Washin~ton , there is a museum and a nearby qift shop. Capitan are the ruins of the New Deal DC and he became the livin~ symbol of Community businesses have capitalized camp for young women. -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Route 66 Archive NEW MEXICO

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Route 66 archive NEW MEXICO Rev. September 2016 Box 1 Accommodations Lists of motels and hotels acquired from internet sources, circa 2001. Articles and press cuttings: 1930s-2004 1 “Route 66: Across 1930s New Mexico. Excerpt from The WPA Guide to 1930s New Mexico . “US 66 Opened to Travel: New Program is Planned.” New Mexico: The Highway Journal , Dec 1937. Sagebrush Lawyer . Arthur Thomas Hannett, 1964. Excerpt. “Route 66: The Long and Lonesome Main Street of the West.” Today’s Empire, Jun 1982. 2 “Buckle Up: Let’s Get Some Kicks.” The Albuquerque Tribune , Jun 1990. “The New Mexico Misunderstanding.” El Palacio , Summer 1994. “Dad Got His Kicks Building Route 66.” Reminisce , Mar/Apr 1995. “The Interstates Midlife Crisis. The Albuquerque Tribune , Jun 1996. “Not Too Many Kicks Now Along Route 66.” Phoenix Newspapers, Inc., Oct 1997. “N.Y. Artists Win Socorro Commission.” Albuquerque Journal , Nov 1997. “State Planning to Save Bridge to American Past.” Albuquerque Journal , Mar 1998. “Speed Reads.” The Albuquerque Tribune , Apr 1998. “Museum Exhibit Tribute to Route 66.” Albuquerque Journal , Jul 1999. “Dig This!” Albuquerque Journal , Jul 1999. “Signs of Life.” Albuquerque Journal , Aug 1999. “County Shares Route 66 History.” Albuquerque Journal , Aug 1999. “Road to Yesterday.” Albuquerque Journal , Aug 2000. 1 “Plan to Help Restore the Kicks on Old Route 66 Gets a $10 Million Boost.” The San Diego Union-Tribune , Aug 1999. “Mother Road Gold.” Albuquerque Journal , Sept 1999. “First a Trail, Then Two Rails and a Road.” Albuquerque Journal , Sept 1999. “Calendar Brings State’s History Into Focus.” Albuquerque Journal , Dec 1999.