Gastroesophageal Reflux in Patients with Subglottic Stenosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Management and Outcome of Tracheobronchial Malacia and Stenosis Presenting to the Paediatric Intensive Care Unit

Intensive Care Med 52001) 27: 722±729 DOI 10.1007/s001340000822 NEONATAL AND PEDIATRIC INTENSIVE CARE David P.Inwald Current management and outcome Derek Roebuck Martin J.Elliott of tracheobronchial malacia and stenosis Quen Mok presenting to the paediatric intensive care unit Abstract Objective: To identify fac- but was not related to any other fac- Received: 10 July 2000 Final Revision received: 14 Oktober 2000 tors associated with mortality and tor. Patients with stenosis required a Accepted: 24 October 2000 prolonged ventilatory requirements significantly longer period of venti- Published online: 16 February 2001 in patients admitted to our paediat- latory support 5median length of Springer-Verlag 2001 ric intensive care unit 5PICU) with ventilation 59 days) than patients tracheobronchial malacia and with malacia 539 days). stenosis diagnosed by dynamic con- Conclusions: Length of ventilation Dr Inwald was supported by the Medical Research Council. This work was jointly trast bronchograms. and bronchographic diagnosis did undertaken in Great Ormond Street Hos- Design: Retrospective review. not predict survival. The only factor pital for Children NHSTrust, which re- Setting: Tertiary paediatric intensive found to contribute significantly to ceived a proportion of its funding from the care unit. mortality was the presence of com- NHSExecutive; the views expressed in this Patients: Forty-eight cases admitted plex cardiac and/or syndromic pa- publication are those of the authors and not to our PICU over a 5-year period in thology. However, patients with necessarily those of the NHSexecutive. whom a diagnosis of tracheobron- stenosis required longer ventilatory chial malacia or stenosis was made support than patients with malacia. -

The Role of Larygotracheal Reconstruction in the Management of Recurrent Croup in Patients with Subglottic Stenosis

International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 82 (2016) 78–80 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijporl The role of larygotracheal reconstruction in the management of recurrent croup in patients with subglottic stenosis a,b,c, a,b a,d,e Bianca Siegel *, Prasad Thottam , Deepak Mehta a Department of Pediatric Otolaryngology, Childrens Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, Pittsburgh, PA, USA b Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, MI, USA c Wayne State University School of Medicine Department of Otolaryngology, Detroit, MI, USA d Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, TX, USA e Baylor University School of Medicine Department of Otolaryngology, Houston, TX, USA A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Objectives: To determine the role of laryngotracheal reconstruction for recurrent croup and evaluate Received 16 October 2015 surgical outcomes in this cohort of patients. Received in revised form 4 January 2016 Methods: Retrospective chart review at a tertiary care pediatric hospital. Accepted 6 January 2016 Results: Six patients who underwent laryngotracheal reconstruction (LTR) for recurrent croup with Available online 13 January 2016 underlying subglottic stenosis were identified through a search of our IRB-approved airway database. At the time of diagnostic bronchoscopy, all 6 patients had grade 2 subglottic stenosis. All patients were Keywords: treated for reflux and underwent esophageal biopsies at the time of diagnostic bronchoscopy; 1 patient Laryngotracheal reconstruction had eosinophilic esophagitis which was treated. All patients had a history of at least 3 episodes of croup Recurrent croup in a 1 year period requiring multiple hospital admissions. -

Subglottic Stenosis: Current10.5005/Jp-Journals-10001-1272 Concepts and Recent Advances Review Article

IJHNS Subglottic Stenosis: Current10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1272 Concepts and Recent Advances REVIEW ARTICLE Subglottic Stenosis: Current Concepts and Recent Advances 1Oshri Wasserzug, 2Ari DeRowe ABSTRACT Signs and Symptoms Subglottic stenosis is considered one of the most complex and The symptoms of SGS in children are closely related to challenging aspects of pediatric otolaryngology, with the most the degree of airway narrowing. Grade I SGS is usually common etiology being prolonged endotracheal intubation. The asymptomatic until an upper respiratory tract infection surgical treatment of SGS can be either endoscopic or open, but recent advances have pushed the limits of the endoscopic occurs, when respiratory distress and stridor, which are approach so that in practice an open laryngotracheal surgical the hallmarks of SGS, appear. Grades II and III stenosis approach is considered only after failed attempts with an can cause biphasic stridor, air hunger, dyspnea, and endoscopic approach. In this review we discuss these advances, suprasternal, intercostal, and diaphragmatic retractions. along with current concepts regarding the diagnosis and Prolonged or recurrent episodes of croup should raise treatment of subglottic stenosis in children. suspicion for SGS. Keywords: Direct laryngoscopy, Endoscopic surgery, Laryngo- At times, the appearance of SGS may be insidious and tracheal surgery, Prolonged intubation, Subglottic stenosis. progressive. It is important to recognize that a compro- How to cite this article: Wasserzug O, DeRowe A. Subglottic Stenosis: Current Concepts and Recent Advances. Int J Head mised airway in a child can lead to rapid deterioration Neck Surg 2016;7(2):97-103. and require immediate appropriate intervention to avoid Source of support: Nil a catastrophic outcome. -

Stridor in the Newborn

Stridor in the Newborn Andrew E. Bluher, MD, David H. Darrow, MD, DDS* KEYWORDS Stridor Newborn Neonate Neonatal Laryngomalacia Larynx Trachea KEY POINTS Stridor originates from laryngeal subsites (supraglottis, glottis, subglottis) or the trachea; a snoring sound originating from the pharynx is more appropriately considered stertor. Stridor is characterized by its volume, pitch, presence on inspiration or expiration, and severity with change in state (awake vs asleep) and position (prone vs supine). Laryngomalacia is the most common cause of neonatal stridor, and most cases can be managed conservatively provided the diagnosis is made with certainty. Premature babies, especially those with a history of intubation, are at risk for subglottic pathologic condition, Changes in voice associated with stridor suggest glottic pathologic condition and a need for otolaryngology referral. INTRODUCTION Families and practitioners alike may understandably be alarmed by stridor occurring in a newborn. An understanding of the presentation and differential diagnosis of neonatal stridor is vital in determining whether to manage the child with further observation in the primary care setting, specialist referral, or urgent inpatient care. In most cases, the management of neonatal stridor is outside the purview of the pediatric primary care provider. The goal of this review is not, therefore, to present an exhaustive review of causes of neonatal stridor, but rather to provide an approach to the stridulous newborn that can be used effectively in the assessment and triage of such patients. Definitions The neonatal period is defined by the World Health Organization as the first 28 days of age. For the purposes of this discussion, the newborn period includes the first 3 months of age. -

A Case of Tracheal Stenosis As an Isolated Form of Immunoproliferative Hyper-Igg4 Disease in a 17-Year-Old Girl

children Case Report A Case of Tracheal Stenosis as an Isolated Form of Immunoproliferative Hyper-IgG4 Disease in a 17-Year-Old Girl Natalia Gabrovska 1,*, Svetlana Velizarova 1, Albena Spasova 1, Dimitar Kostadinov 1, Nikolay Yanev 1, Hristo Shivachev 2, Edmond Rangelov 2, Yanko Pahnev 2, Zdravka Antonova 2, Nikola Kartulev 2, Ivan Terziev 3 and Kaloyan Gabrovski 4 1 Department of Pulmonary Diseases, Multiprofile Hospital for Active Treatment of Pulmonary Diseases “St. Sofia”, Medical University–Sofia, 1431 Sofia, Bulgaria; [email protected] (S.V.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (D.K.); [email protected] (N.Y.) 2 Department of Pediatric Thoracic Surgery, Pediatric Surgery Clinic, University Multiprofile Hospital for Active Treatment and Emergency Medicine “N. I. Pirogov”, 1606 Sofia, Bulgaria; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (E.R.); [email protected] (Y.P.); [email protected] (Z.A.); [email protected] (N.K.) 3 Department of Pathology, University Hospital ‘’Tsaritsa Uoanna–ISUL”, 1527 Sofia, Bulgaria; [email protected] 4 Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital “St. Ivan Rilski”, Medical University–Sofia, 1431 Sofia, Bulgaria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +359-887-931-009 Abstract: Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a lymphoproliferative disease which is described almost exclusively in adults. There are only a few pediatric patients who have been observed with this disorder. Here, we describe a rare case of IgG4-RD in a 17-year-old girl with Citation: Gabrovska, N.; Velizarova, a single manifestation—tracheal stenosis without previous intubation or other inciting event. -

Respiratory Complications and Goldenhar Syndrome

breathe case presentations.qxd 06/03/2007 17:56 Page 15 CASE PRESENTATION Respiratory complications and Goldenhar syndrome Case report W. Jacobs1 A 29-year-old female was referred to hospital A. Vonk Noordegraaf1 with progressive asthmatic complaints. On pre- R.P. Golding2 sentation, the patient had been experiencing J.G. van den Aardweg3 orthopnoea, an audible wheeze during daily P.E. Postmus1 activities, and sporadic coughing without spu- tum production. The patient had a history of recurrent airway infections and a 5-kg weight Depts of 1Pulmonary Medicine loss during the previous year, and had stopped and 2Radiology, Vrije Universiteit smoking several years before. She was known to Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, have oculo-auriculo-vertebral (OAV) syndrome, and 3Dept of Pulmonary i.e. Goldenhar syndrome, which is a develop- Medicine, Medisch Centrum mental disorder involving mainly first and sec- Alkmaar, The Netherlands. ond branchial arch anomalies. On physical examination, she was not dys- pnoeic at rest, and had a respiratory rate of Correspondence: -1 -1 14 breaths·min , pulse 80 beats·min , blood W. Jacobs pressure 110/70 mmHg and temperature Dept of Pulmonary Medicine Figure 1 37.9°C. The left hemifacial structures and the Vrije Universiteit Medisch Centrum Postero-anterior chest radiograph. left hemithorax were underdeveloped. A chest Postbus 7057 examination revealed a systolic heart murmur 1007 MB Amsterdam grade 2/6 over the apex, and inspiratory and The Netherlands expiratory wheezing over both lungs. There was Task 1 Fax: 31 204444328 E-mail: [email protected] no oedema or clubbing. Arterial blood gas analy- Interpret the chest radiograph. -

Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis: a Review

1111 Editorial Section of Interventional Pulmonology Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: a review Carlos Aravena1,2, Francisco A. Almeida1, Sanjay Mukhopadhyay3, Subha Ghosh4, Robert R. Lorenz5, Sudish C. Murthy6, Atul C. Mehta1 1Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA; 2Department of Respiratory Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile; 3Department of Pathology, Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, 4Department of Diagnostic Radiology, 5Head and Neck Institute, 6Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Heart and Vascular Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: C Aravena, AC Mehta; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: C Aravena, AC Mehta; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Atul C. Mehta, MD, FCCP. Lerner College of Medicine, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave, A-90, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Idiopathic subglottic stenosis (iSGS) is a fibrotic disease of unclear etiology that produces obstruction of the central airway in the anatomic region under the glottis. The diagnosis of this entity is difficult, usually delayed and confounded with other common respiratory diseases. No apparent etiology is identified even after a comprehensive workup that includes a complete history, physical examination, pulmonary function testing, auto-antibodies, imaging studies, and endoscopic procedures. This approach, however, helps to exclude other conditions such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). It is also helpful to characterize the lesion and outline management strategies. -

Chest Wall Abnormalities and Their Clinical Significance in Childhood

Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 15 (2014) 246–255 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Paediatric Respiratory Reviews CME article Chest Wall Abnormalities and their Clinical Significance in Childhood Anastassios C. Koumbourlis M.D. M.P.H.* Professor of Pediatrics, George Washington University, Chief, Pulmonary & Sleep Medicine, Children’s National Medical Center EDUCATIONAL AIMS 1. The reader will become familiar with the anatomy and physiology of the thorax 2. The reader will learn how the chest wall abnormalities affect the intrathoracic organs 3. The reader will learn the indications for surgical repair of chest wall abnormalities 4. The reader will become familiar with the controversies surrounding the outcomes of the VEPTR technique A R T I C L E I N F O S U M M A R Y Keywords: The thorax consists of the rib cage and the respiratory muscles. It houses and protects the various Thoracic cage intrathoracic organs such as the lungs, heart, vessels, esophagus, nerves etc. It also serves as the so-called Scoliosis ‘‘respiratory pump’’ that generates the movement of air into the lungs while it prevents their total collapse Pectus Excavatum during exhalation. In order to be performed these functions depend on the structural and functional Jeune Syndrome VEPTR integrity of the rib cage and of the respiratory muscles. Any condition (congenital or acquired) that may affect either one of these components is going to have serious implications on the function of the other. Furthermore, when these abnormalities occur early in life, they may affect the growth of the lungs themselves. The followingarticlereviewsthe physiology of the respiratory pump, providesa comprehensive list of conditions that affect the thorax and describes their effect(s) on lung growth and function. -

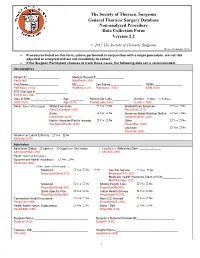

Annotated Non-Analyzed Procedure

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons General Thoracic Surgery Database Non-analyzed Procedure Data Collection Form Version 2.2 © 2012 The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Revised February, 2012 • Procedures listed on this form, unless performed in conjunction with a major procedure, are not risk adjusted or analyzed and are not mandatory to collect. • If the Surgeon Participant chooses to track these cases, the following data set is recommended. Demographics Patient ID: ___________________ Medical Record #:_________________ PatID (80) MedRecN (100) First Name:__________________ MI:_____ Last Name:___________________ SSN#:_________________ PatFName (110) PatMInit (120) PatLName (130) SSN (140) STS Trial Link #:____________________ STSTLink (150) Date of Birth:____/____/______ Age: ________ Patient Zip Code:__________ Gender: Male Female DOB (160) Age (170) PostalCode (180) Gender (190) Race: Select all that apply → White/Caucasian Yes No Black/African American Yes No RaceCaucasian (200) RaceBlack (210) Asian Yes No American Indian/Alaskan Native Yes No RaceAsian (220) RaceNativeAm (230) Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Yes No Other Yes No RacNativePacific (240) RaceOther (250) Unknown Yes No RaceUnk (260) Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity: Yes No Ethnicity (270) Admission Admission Status: Inpatient Outpatient / Observation If Inpatient → Admission Date: ____/___/_____ AdmissionStat (280) AdmitDt (290) Payor: Select all that apply ↓ Government Health Insurance: Yes No PayorGov (300) If Yes: Select all that apply: ↓ Medicare Yes No If Yes → Fee For Service: Yes No PayorGovMcare(310) MedicareFFS (320) Medicare Health Insurance Claim (HIC)#:____________ MHICNumber (331) Medicaid Yes No Military Health Care Yes No PayorGovMcaid(340) PayorGovMil(350) State-Specific Plan Yes No Indian Health Service Yes No PayorGovState(360) PayorGovIHS(370) Commercial Health Insurance Yes No Non-U.S. -

Clinical Review Laryngotracheal Anomalies in Children with Craniofacial Syndromes

Clinical Review Laryngotracheal Anomalies in Children With Craniofacial Syndromes Frank A. Papay, MD, FACS* Vincent P. McCarthy, MD† Isaac Eliachar, MD‡ James Arnold, MD§ Cleveland, Ohio INTRODUCTION sleep apnea. Recent literature reviews have ad- dressed the causes of sleep apnea in various cranio- he formation of the nasal oropharyngeal airway facial syndromes and will not be discussed in detail in conjunction with the laryngotracheal airway T herein.1,2 Craniofacial syndromes that involve an ab- and its related structures is a complex process de- normal anterior and middle cranial base in associa- pendent on the separate yet interrelated ontologic tion with mid-facial maxillary hypoplasia often have development of the mouth, nose, pharynx, larynx, narrow nasopharyngeal channels causing nasopha- and the tracheo-bronchial tree. These relationships ryngeal airway constriction. In neonates who are ob- are also influenced by the adjacent formation of the ligate nasal breathers, this may pose difficulties such posterior cranial base, anterior craniofacial skeleton, as a physiologic choanal atresia type of nasopharyn- neck, and adjacent thoracic structures. Not surpris- geal obstruction. In addition, the mid to lower cranial ingly, a vast array of airway anomalies can occur base in close association with the oropharyngeal cav- when each interrelated adjacent structure is abnor- ity, may cause respiratory comprise with the base of mal. Because of its vital nature, life-threatening air- the tongue and the glottic opening. Patients having way anomalies are apparent at birth or soon after. cranial base, maxillary midfacial hypoplasia with an Respiratory distress, cyanosis, difficulty feeding, and additional mandibular hypoplasia, will in essence visually observed abnormalities can lead to an early have partial obstruction in all zones of the upper diagnosis. -

1 Pediatric Pulmonary Puzzlers Physical Examination

Pediatric pulmonary puzzlers Bruce K. Rubin MEngr, MD, MBA, FAARC Jessie Ball duPont Professor and Chairman, Pediatrics Physician in Chief Children’s Hospital of Richmond Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine [1] Noisy breathing in a baby A three month old baby comes to well child check with noisy breathing “since birth” He is feeding vigorously with no choking or excessive spitting up and no respiratory distress with feeding. He has hiccups often No history of pneumonia or otitis media Physical Examination Height and weight 50% for age. Not hypoxemic. Happy baby HEENT: Normal including intact palate by palpation. No head bobbing Neck: No masses Chest: No deformity or retractions Lungs: bilaterally equal air entry with coarse breath sounds and loud inspiratory stridor, no wheezes Investigations? 1 Laryngomalacia Most common cause of chronic stridor in infancy - 60-75% Prolapse of epiglottis or arytenoids into glottis causes upper airway obstruction Should NOT be confused with tracheomalacia Occasionally there is slow maturation of other cartilage May occurs as part of cartilage dysplasia syndrome Laryngomalacia Sometimes there is a family history Coexisting GE reflux is common and due to air swallowing Air swallowing also causes hiccups, flatulence, and abdominal distention Tend to be vigorous feeders and grow well Stridor improves in prone position 2 Laryngomalacia Time Course: Usually begins after 2-4 weeks Significant improvement by 1 year Mild symptoms persist for 2-4 years Need for surgical intervention determined by -

Chronic Stridor in Children Developed by Hannah Kraicer-Melamed and Dr. Jonathan Rayment for Pedscases.Com January 9, 2019 Intro

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Chronic Stridor in Children” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Chronic Stridor in Children Developed by Hannah Kraicer-Melamed and Dr. Jonathan Rayment for PedsCases.com January 9, 2019 Introduction This podcast was written by both Hannah Kraicer-Melamed and Dr. Jonathan Rayment. I’m Hannah, a student at McMaster University and Dr. Rayment is a Pediatric Respirologist at B.C. Children’s Hospital. Objectives Today’s podcast will discuss an approach to chronic stridor in children. Stridor is a common, distressing problem in children. We think about the common causes of acute stridor like croup, epiglottitis, or inhaled foreign bodies, but what happens when it doesn’t go away? There are a number of important structural and functional causes of stridor that a physician caring for children needs to consider. After listening to this podcast, the learner should be to: 1. Define stridor and differentiate it from wheeze 2. List the major causes of chronic stridor 3. Order appropriate investigation for a child with chronic stridor 4. Understand the management of the major causes of chronic stridor If this is a newer topic for you, you might want to check out the PedsCases podcasts on Evaluation of Stridor and Croup, before listening to the rest of this podcast. Case Let’s start with a case. You are working in a community clinic, and your next appointment is Charlie, a 4-month-old whose parents are bringing them in for assessment of noisy breathing.