Send in the Clones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

French Animation History Ebook

FRENCH ANIMATION HISTORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Richard Neupert | 224 pages | 03 Mar 2014 | John Wiley & Sons Inc | 9781118798768 | English | New York, United States French Animation History PDF Book Messmer directed and animated more than Felix cartoons in the years through This article needs additional citations for verification. The Betty Boop cartoons were stripped of sexual innuendo and her skimpy dresses, and she became more family-friendly. A French-language version was released in Mittens the railway cat blissfully wanders around a model train set. Mat marked it as to-read Sep 05, Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. In , Max Fleischer invented the rotoscope patented in to streamline the frame-by-frame copying process - it was a device used to overlay drawings on live-action film. First Animated Feature: The little-known but pioneering, oldest-surviving feature-length animated film that can be verified with puppet, paper cut-out silhouette animation techniques and color tinting was released by German film-maker and avante-garde artist Lotte Reiniger, The Adventures of Prince Achmed aka Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed , Germ. Books 10 Acclaimed French-Canadian Writers. Rating details. Dave and Max Fleischer, in an agreement with Paramount and DC Comics, also produced a series of seventeen expensive Superman cartoons in the early s. Box Office Mojo. The songs in the series ranged from contemporary tunes to old-time favorites. He goes with his fox terrier Milou to the waterfront to look for a story, and finds an old merchant ship named the Karaboudjan. The Fleischers launched a new series from to called Talkartoons that featured their smart-talking, singing dog-like character named Bimbo. -

Film Essay for "Modern Times"

Modern Times By Jeffrey Vance No human being is more responsible for cinema’s ascendance as the domi- nant form of art and entertainment in the twentieth century than Charles Chaplin. Yet, Chaplin’s importance as a historic figure is eclipsed only by his creation, the Little Tramp, who be- came an iconic figure in world cinema and culture. Chaplin translated tradi- tional theatrical forms into an emerg- ing medium and changed both cinema and culture in the process. Modern screen comedy began the moment Chaplin donned his derby hat, affixed his toothbrush moustache, and Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character finds he has become a cog in the stepped into his impossibly large wheels of industry. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. shoes for the first time. “Modern Times” is Chaplin’s self-conscious subjects such as strikes, riots, unemployment, pov- valedictory to the pantomime of silent film he had pio- erty, and the tyranny of automation. neered and nurtured into one of the great art forms of the twentieth century. Although technically a sound The opening title to the film reads, “Modern Times: a film, very little of the soundtrack to “Modern Times” story of industry, of individual enterprise, humanity contains dialogue. The soundtrack is primarily crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” At the Electro Chaplin’s own musical score and sound effects, as Steel Corporation, the Tramp is a worker on a factory well as a performance of a song by the Tramp in gib- conveyor belt. The little fellow’s early misadventures berish. This remarkable performance marks the only at the factory include being volunteered for a feeding time the Tramp ever spoke. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

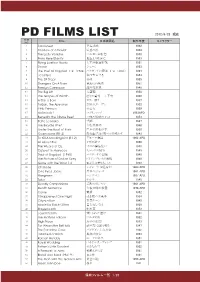

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Vaudeville Extravaganza! Live! 5 - Big Acts -5

ET KLE N IN JA Sept. 15, 8 pm, Alex Film Society presents VAUDEVILLE EXTRAVAGANZA! LIVE! 5 - BIG ACTS -5 a n d h s er oy Parlor B THE NIGHT BLOOMING JAZZMEN NOSTALGIC MUSIC REID & FAVERSHAM FARRAH SIEGEL COMEDY THRILLS RUSTY & ERIC GRIFF BUSS SWELLS FOOLOLOGY PLUS, On The Big Screen! Laurel & Hardy in THE MUSIC BOX (1932) The Three Stooges® in AN ACHE IN EVERY STAKE (1941) Alex Film Society presents the 8th annual VAUDEVILLE EXTRAVAGANZA! September 15, 2007, 8 pm. Alex Theatre, Glendale ach year, in the spirit of Vaudeville, and to THE MUSIC BOX honor the early history of the Alex Theatre, Black & White – 30 minutes – 1932 Ewe include a film portion as part of our Hal Roach Studios Inc. program. For our 8th annual event, we feature two shorts by the most enduring comedy teams in film Stan Laurel ................... Stanley history: Laurel and Hardy and The Three Stooges®. Oliver Hardy ................. Oliver Billy Gilbert .................. Prof. von Schwarzenhoffen* These films have a common theme as well, using a William Gillespie ........... Piano salesman* huge flight of stairs as an obstacle for our heroes. Charlie Hall .................. Postman* Stan and Ollie’s 1932 short, The Music Box, is Hazel Howell ................ Mrs. von Schwarzenhoffen* actually a remake of “Hats Off” a lost silent they did Lilyan Irene .................. Nursemaid* in 1927. Here the boys have to move a piano up a Sam Lufkin................... Policeman* huge flight of stairs (in the original it was a washing machine). Nearly ten years later, in An Ache in Directed by .................. James Parrott Every Stake, Larry, Moe and Curly seem to have Produced by ................ -

Best Picture of the Yeari Best. Rice of the Ear

SUMMER 1984 SUP~LEMENT I WORLD'S GREATEST SELECTION OF THINGS TO SHOW Best picture of the yeari Best. rice of the ear. TERMS OF ENDEARMENT (1983) SHIRLEY MacLAINE, DEBRA WINGER Story of a mother and daughter and their evolving relationship. Winner of 5 Academy Awards! 30B-837650-Beta 30H-837650-VHS .............. $39.95 JUNE CATALOG SPECIAL! Buy any 3 videocassette non-sale titles on the same order with "Terms" and pay ONLY $30 for "Terms". Limit 1 per family. OFFER EXPIRES JUNE 30, 1984. Blackhawk&;, SUMMER 1984 Vol. 374 © 1984 Blackhawk Films, Inc., One Old Eagle Brewery, Davenport, Iowa 52802 Regular Prices good thru June 30, 1984 VIDEOCASSETTE Kew ReleMe WORLDS GREATEST SHE Cl ION Of THINGS TO SHOW TUMBLEWEEDS ( 1925) WILLIAMS. HART William S. Hart came to the movies in 1914 from a long line of theatrical ex perience, mostly Shakespearean and while to many he is the strong, silent Western hero of film he is also the peer of John Ford as a major force in shaping and developing this genre we enjoy, the Western. In 1889 in what is to become Oklahoma Territory the Cherokee Strip is just a graz ing area owned by Indians and worked day and night be the itinerant cowboys called 'tumbleweeds'. Alas, it is the end of the old West as the homesteaders are moving in . Hart becomes involved with a homesteader's daughter and her evil brother who has a scheme to jump the line as "sooners". The scenes of the gigantic land rush is one of the most noted action sequences in film history. -

Hands Up! by Steve Massa

Hands Up! By Steve Massa Raymond Griffith is one of silent come- dy’s unjustly forgotten masters, whose onscreen persona was that of a calm, cool, world-weary bon vivant – some- thing like Max Linder on Prozac. After a childhood spent on stage touring in stock companies and melodramas, he ended up in films at Vitagraph in 1914 and went on to stints at Sennett,- L Ko, and Fox as a comedy juvenile. Not mak- ing much of an impression due to a lack of a distinctive character, he went be- hind the camera to become a gagman, working at Sennett and for other comics like Douglas MacLean. In 1922 he re- turned to acting and became the ele- gant, unflappable ladies’ man. Stealing comedies such as “Changing Husbands,” “Open All Night,” and “Miss Bluebeard” (all 1924) away ing very popular with his character of “Ambrose,” a put- their respective stars Paramount decided to give him his upon everyman with dark-circled eyes and a brush mous- own series, and he smarmed his way through ten starring tache. Leaving Sennett in 1917 he continued playing Am- features starting with “The Night Club” (1925). brose for L-Ko, Fox, and the independent Poppy Come- dies and Perry Comedies. His career stalled in the early “Hands Up!” (1926) soon followed, and is the perfect 1920s when he was blacklisted by an influential produc- showcase for Griffith’s deft comic touch and sly sense of er, but his old screen mate Charlie Chaplin came to the the absurd. The expert direction is by Clarence Badger, rescue and made Mack part of his stock company in films who started in the teens with shorts for Joker and Sen- such as “The Idle Class” (1921) and “The Pilgrim” (1923). -

All Texts by Genre, Becoming Modern: America in the 1920S

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION k National Humanities Center Primary Source Collection BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S americainclass.org/sources/becomingmodern A collection of primary resources—historical documents, literary texts, and works of art— thematically organized with notes and discussion questions 1 __Resources by Genre__ ___Each genre is ordered by Theme: THE AGE, MODERNITY, MACHINE, PROSPERITY, DIVISION.___ External sites are noted in small caps. COLLECTIONS: CONTEMPORARY COMMENTARY NONFICTION, FICTION, ILLUSTRATIONS, CARTOONS, etc.* THE AGE 1 “The Age” PROSPERITY 1 “Age of Prosperity” MODERNITY 1 Modern Youth PROSPERITY 2 Business MODERNITY 2 Modern Woman PROSPERITY 3 Consumerism MODERNITY 3 Modern Democracy PROSPERITY 4 Crash MODERNITY 4 Modern Faith DIVISIONS 1 Ku Klux Klan MODERNITY 5 Modern City: The Skyscraper DIVISIONS 2 Black & White MACHINE 1 “Machine Age” DIVISIONS 3 City & Town MACHINE 3 Automobile DIVISIONS 5 Religion & Science MACHINE 5 Radio DIVISIONS 6 Labor & Capital DIVISIONS 7 Native & Foreign DIVISIONS 8 “Reds” & “Americans” POLITICAL CARTOON COLLECTIONS THE AGE 3 –Chicago Tribune political cartoons: 24 cartoons (two per year, 1918-1929) PROSPERITY 1 –“Age of Prosperity”: 12 cartoons PROSPERITY 4 –Crash: 12 cartoons DIVISIONS 1 –Ku Klux Klan: 16 cartoons DIVISIONS 2 –Black & White: 18 cartoons DIVISIONS 4 –Wets & Drys: 8 cartoons DIVISIONS 6 –Labor & Capital: 14 cartoons DIVISIONS 7 –Native & Foreign: 6 cartoons DIVISIONS 8 –“Reds” & “Americans”: 8 cartoons 1 Image: Florine Stettheimer, The Cathedrals of Broadway, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. Gift of Ettie Stettheimer, 1953. 53.24.3. Image: Art Resource, NY. Reproduced by permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; cropping permission request in process. -

Hannah Arendt, Charlie Chaplin and the Hidden Jewish Tradition

LILIANE WEISSBERG' HANNAH ARENDT, CHARLIE CHAPLIN, AND ffiE HIDDEN JEWISH TRADITION 1. THE HIDDEN TRADITION ln 1944, Hannah Arendt publishes her essay, "TheJew as Pariah: The Hidden Tradition." 1 By this time the German political philosopher has settled down in her last place of exile, New York City, Europe is at war; European Jews are sent to the camps, and A.rendt, who was never to shy away from any criticism directed atJews themselves, reflects upon their fate; she considers any missed opportunities in their social and political engagement. Arendt has just completed her first book since writing her dissertation on St. Augustine,2 a study entitled, Rahel Varnhagen: Ibe Life of afewess. She had begun the book in 1927, and most of it had been written in Berlin. Yet, Arendt fled to Paris with the incomplete manuscript in 1933. The book is first to appear in English translation in 1956.3 Arendt is also writing essays on the contemporary situation of Jews and Zionism far various American and German A.merican papers, and she begins work on what will become her major oeuvre, Ibe Origins of Totalitarianism.4 The füst section of Ibe Origins is entitlec.l, "Antisemitism," and will concern the history of the Jews as well. How could one understand what had happened to this people, and how could Jews themselves have prevented these events? These are questions that have haunted Arendt since the 1930s. Already, in Rahel Varnhagen, Arendt deplores the lack of political commitment on the side of)ews, along with their long-standing rejection of or oblivion to-political action. -

Sennett Creative Campus, Echo Park's Newest Modern

SENNETT CREATIVE CAMPUS, ECHO PARK’S NEWEST MODERN/CREATIVE OFFICE ENVIRONMENT 1745- 1759 GLENDALE BOULEVARD, ECHO PARK, CALIFORNIA David Aschkenasy Executive Vice President Phone 310.272.7381 email [email protected] The Sennett Creative Campus is greater Los Angeles’ most unique creative office destination. The Spaces: +/- 6,500 - 14,000 sq ft Campus offers one of the largest and architecturally significant, contiguous office spaces available. Rate: $1.95 psf, Modified Gross Originally built in 1946, and fully modernized and renovated in 2015, 1745-1759 N Glendale Blvd is a Parking: In rear of building, free of charge 30,000 Square Foot +/- campus environment that brings the glory of old Hollywood to life in the 21st Century. Comprised of 4 buildings, outdoor patios and surface parking lots, 1745-1759 N Glendale Features: • Exposed Ceilings Blvd is equipped with dramatic exposed wood truss ceilings, new HVAC & electric, polished concrete • Loading Dock and hardwood floors, brand new restrooms, reclaimed wood kitchens, multiple skylights and ample • Concrete & Hardwood Flooring parking. Greater Los Angeles is very limited with regard to true creative office space of this scale and • Exposed HVAC Ducting caliber. While there is availability in Silicon Beach (Venice and Santa Monica), Hollywood, and the • High Ceilings Arts District, the Sennett Creative Campus offers the same Creative Office Build outs at a fraction of the price. The Campus is priced at least 50% below these other creative office locations, and offers • Private Exterior Patios free parking for an additional savings. There is also the opportunity to have the exclusive use of the • Skylights rooftop billboard.