Hadjiandreou, Andri. 2014. Intentions and Interpretations: Form, Narrativity and Performance Approaches to the 19Th-Century Piano Ballade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

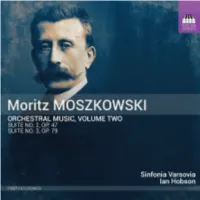

TOCC0557DIGIBKLT.Pdf

MORITZ MOSZKOWSKI: ORCHESTRAL MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Martin Eastick History has not served Moszkowski well. Even before his death in 1925, his star had been on the wane for some years as the evolving ‘Brave New World’ took hold after the Great War in 1918: there was little or no demand for what Moszkowski once had to offer and the musical sensitivities he represented. His name did live on to a limited extent, with the odd bravura piano piece relegated to the status of recital encore, and his piano duets – especially the Spanish Dances – continuing to be favoured in the circles of home music-making. But that was about the limit of his renown until, during the late 1960s, there gradually awoke an interest in nineteenth-century music that had disappeared from the repertoire – and from people’s awareness – and the composers who had been everyday names during their own lifetime, Moszkowski among them. Initially, this ‘Romantic Revival’ was centred mainly on the piano, but it gradually diversified to music in all its forms and continues to this day. Only very recently, though, has attention been given to Moszkowski as a serious composer of orchestral music – with the discovery and performance in 2014 of his early but remarkable ‘lost’ Piano Concerto in B minor, Op. 3, providing an ideal kick-start,1 and the ensuing realisation that here was a composer worthy of serious consideration who had much to offer to today’s listener. In 2019 the status of Moszkowski as an orchestral composer was ramped upwards with the release of the first volume in this Toccata Classics series, featuring his hour-long, four-movement symphonic poem Johanna d’Arc, Op. -

Songs for Piano Alone a Look at Franz Liszt’S Buch Der Lieder Für Piano Allein Books I and Ii

SONGS FOR PIANO ALONE A LOOK AT FRANZ LISZT’S BUCH DER LIEDER FÜR PIANO ALLEIN BOOKS I AND II BY JEREMY RAFAL Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December, 2012 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music __________________________________ Karen Shaw, Chairperson __________________________________ Edmund Battersby, Committee Member __________________________________ Emile Naoumoff, committee member ii Songs for Piano Alone A Look at Franz Liszt’s Buch der Lieder für Piano allein Books I and II Music circles have often questioned the artistic integrity of piano transcriptions: should they should be on the same par as “original works” or are they merely imitations of somebody else’s work? Franz Liszt produced hundreds of piano transcriptions of works by other composers making him one of the leading piano transcriptionists of all time. While transcriptions are the results of rethinking and remolding pre-existing materials, how should we view the “transcriptions” of the composer’s own original work? Liszt has certainly taken much of his original non-piano works and transcribed them for solo piano. But would these really be transcriptions, or different versions? This thesis explores the question of how transcriptions of Liszt’s own works should be treated, particularly the solo piano pieces in the two books of Buch der Lieder für Piano allein. While some pieces are clearly transcriptions of previous art songs, some pieces should really be characterized as independent piano pieces first before art songs. -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Robin Ticciati Grauschumacher Piano Duo – Klaviere Jens Hilse, Henrik M

Ticciati Robin Ticciati GrauSchumacher Piano Duo – Klaviere Jens Hilse, Henrik M. Schmidt – Schlagzeug Bartók: Konzert für zwei Klaviere, Schlagzeug und Orchester / Beethoven: Symphonie Nr. 4 Mo 21.9., 20 Uhr, Philharmonie Programm 2 3 Introduktion Mo 21.9./ 20 Uhr / Philharmonie Zeit der Kreativität Béla Bartók (1881ª1945) Es ist mir eine unbeschreibliche Freude, dass wir uns wieder in der Berliner Konzert für zwei Klaviere, Schlagzeug und Orchester BB 121 (1937/1940) Philharmonie musikalisch begegnen können: Sie, unser engagiertes, kritisches I. Assai lento – Allegro molto Publikum, und wir, die Musikerinnen und Musiker des DSO unter meiner Leitung. II. Lento, ma non troppo Es ist zwar alles ganz anders als vor einem guten halben Jahr, als wir hier zuletzt III. Allegro non troppo spielen konnten: Wir müssen auf Abstand bleiben – Sie im Saal, wir auf der Für die Urau°ührung werden zwei verschiedene Daten angegeben: Bühne; wir müssen Kartenkontingente begrenzen und Programme verkürzen. 14. November 1942 in der Royal Albert Hall, London, durch das London Philharmonic Orchestra unter Aber wir können das Erlebnis Musik wieder direkt und ohne mediale Vermittlung der Leitung von Sir Adrian Boult; Solisten: Louis Kentner und Ilona Kabos (Klavier), Ernest Gillegin und mit Ihnen teilen. Darüber sind wir sehr froh. Frederick Bradshaw (Schlagzeug). 21. Januar 1943 in der New Yorker Carnegie Hall durch das New York Philharmonic Orchestra unter der Leitung von Fritz Reiner; Klaviersolisten: Béla Bartók und seine Frau Ditta Pásztory. Am heutigen Abend präsentieren das DSO und ich erstmals eine Beethoven- Symphonie. Dabei setzen wir die Linie fort, die wir mit Händels ›Messias‹ begon- Ludwig van Beethoven (1770ª1827) nen und mit Mozarts letzten Symphonien weitergeführt haben: Die Streicher Symphonie Nr. -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor

Minnesota Musicians ofthe Cultured Generation Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor The appeal ofAmerica 1) Early life & arrival in Minneapolis 2) Work in Minneapolis 3) Into the out-of-doors 4) Death & appraisal Robert Tallant Laudon Professor Emeritus ofMusicology University ofMinnesota 924 - 18th Ave. SE Minneapolis, Minnesota 55414 (612) 331-2710 [email protected] 2002 Heinrich Hoevel (Courtesy The Minnesota Historical Society) Heinrich Hoevel Heinrich Hoevel German Violinist in Minneapolis and Thorson's Harbor A veritable barrage ofinformation made the New World seem like an answer to all the yearnings ofpeople ofthe various German States and Principalities particularly after the revolution of 1848 failed and the populace seemed condemned to a life of servitude under the nobility and the military. Many of the Forty-Eighters-Achtundvierziger-hoped for a better life in the New World and began a monumental migration. The extraordinary influx of German immigrants into America included a goodly number ofgifted artists, musicians and thinkers who enriched our lives.! Heinrich Heine, the poet and liberal thinker sounded the call in 1851. Dieses ist Amerika! This, this is America! Dieses ist die neue Welt! This is indeed the New World! Nicht die heutige, die schon Not the present-day already Europaisieret abwelkt. -- Faded Europeanized one. Dieses ist die neue Welt! This is indeed the New World! Wie sie Christoval Kolumbus Such as Christopher Columbus Aus dem Ozean hervorzog. Drew from out the depths of -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

MAHANI TEAVE Concert Pianist Educator Environmental Activist

MAHANI TEAVE concert pianist educator environmental activist ABOUT MAHANI Award-winning pianist and humanitarian Mahani Teave is a pioneering artist who bridges the creative world with education and environmental activism. The only professional classical musician on her native Easter Island, she is an important cultural ambassador to this legendary, cloistered area of Chile. Her debut album, Rapa Nui Odyssey, launched as number one on the Classical Billboard charts and received raves from critics, including BBC Music Magazine, which noted her “natural pianism” and “magnificent artistry.” Believing in the profound, healing power of music, she has performed globally, from the stages of the world’s foremost concert halls on six continents, to hospitals, schools, jails, and low-income areas. Twice distinguished as one of the 100 Women Leaders of Chile, she has performed for its five past presidents and in its Embassy, along with those in Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Japan, Ecuador, Korea, Mexico, and symbolic places including Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Chile’s Palacio de La Moneda, and Chilean Congress. Her passion for classical music, her local culture, and her Island’s environment, along with an intense commitment to high-quality music education for children, inspired Mahani to set aside her burgeoning career at the age of 30 and return to her Island to found the non-profit organization Toki Rapa Nui with Enrique Icka, creating the first School of Music and the Arts of Easter Island. A self-sustaining ecological wonder, the school offers both classical and traditional Polynesian lessons in various instruments to over 100 children. Toki Rapa Nui offers not only musical, but cultural, social and ecological support for its students and the area. -

The Harrovian

THE HARROVIAN VOL. CXXXI NO.14 January 26, 2019 As the Karelia Suite concluded, a swift change in the orchestra ORCHESTRAL CONCERT took place, so that only the strings remained on the stage. The Reflection and Thoughts, 19 January, Speech Room second piece began: a Violin Concerto in C Major by Haydn with Jonathan Yuan as soloist. Again, there were three parts to On the cold winter’s evening of Saturday, the School put on its this concerto, beginning with the Allegro moderato, followed the Orchestral Concert in Speech Room. It was a spectacular by Adagio and concluding with the Finale: Presto. There was event and the music was simply stunning. The orchestra, without a charming and delightful entrance by the violins, violas and a doubt, managed to deliver something astonishing and magical cellos in the Allegro moderato section and, as the soloist took that night. The standard and the quality of the sound that it over, there was a light, progressing harmony to accompany produced was startling, and everyone performed with great him. The soloist, Jonathan Yuan, performance his part solidly. enthusiasm, passion and emotion for the three pieces of music. Overall, the orchestra’s commencement was strong and majestic. The Adagio section was performed exceptionally well with a fine, clear-cut rhythm to distinguish the soloist from the accompaniment of the strings. There was an elegant and artistic start from the soloist, including a mesmerising harmony of the violins, violas and cellos with their unadorned yet graceful pizzicato passage. The Adagio movement was utterly striking and charming, saturated with peaceful, soothing and emotional phrases. -

April 2021 Vol.22, No. 4 the Elgar Society Journal 37 Mapledene, Kemnal Road, Chislehurst, Kent, BR7 6LX Email: [email protected]

Journal April 2021 Vol.22, No. 4 The Elgar Society Journal 37 Mapledene, Kemnal Road, Chislehurst, Kent, BR7 6LX Email: [email protected] April 2021 Vol. 22, No. 4 Editorial 3 President Sir Mark Elder, CH, CBE Ballads and Demons: a context for The Black Knight 5 Julian Rushton Vice-President & Past President Julian Lloyd Webber Elgar and Longfellow 13 Arthur Reynolds Vice-Presidents Diana McVeagh Four Days in April 1920 23 Dame Janet Baker, CH, DBE Some notes regarding the death and burial of Alice Elgar Leonard Slatkin Relf Clark Sir Andrew Davis, CBE Christopher Robinson, CVO, CBE Book reviews 36 Andrew Neill Arthur Reynolds, Relf Clark Martyn Brabbins Tasmin Little, OBE CD Reviews 44 Christopher Morley, Neil Mantle, John Knowles, Adrian Brown, Chairman Tully Potter, Andrew Neill, Steven Halls, Kevin Mitchell, David Morris Neil Mantle, MBE DVD Review 58 Vice-Chairman Andrew Keener Stuart Freed 100 Years Ago... 60 Treasurer Kevin Mitchell Peter Smith Secretary George Smart The Editors do not necessarily agree with the views expressed by contributors, nor does the Elgar Society accept responsibility for such views. Front Cover: Portrait photograph of Longfellow taken at ‘Freshfields’, Isle of Wight in 1868 by Julia Margaret Cameron. Courtesy National Park Service, Longfellow Historical Site. Notes for Contributors. Please adhere to these as far as possible if you deliver writing (as is much Editorial preferred) in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Copyright: it is the contributor’s responsibility to be reasonably sure that copyright permissions, if required, are obtained. Professor Russell Stinson, the musicologist, in his chapter on Elgar in his recently issued Bach’s Legacy (reviewed in this issue) states that Elgar had ‘one of the greatest minds in English music’.1 Illustrations (pictures, short music examples) are welcome, but please ensure they are pertinent, This is a bold claim when considering the array of intellectual ability in English music ranging cued into the text, and have captions. -

The Psycho-Physiological Effects of Volume, Pitch, Harmony and Rhythm in the Development of Western Art Music Implications for a Philosophy of Music History

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 1981 The Psycho-physiological Effects of Volume, Pitch, Harmony and Rhythm in the Development of Western Art Music Implications for a Philosophy of Music History Wolfgang Hans Stefani Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stefani, Wolfgang Hans, "The Psycho-physiological Effects of Volume, Pitch, Harmony and Rhythm in the Development of Western Art Music Implications for a Philosophy of Music History" (1981). Master's Theses. 26. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/26 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University school o f Graduate Studies THE PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF VOLUME, PITCH, HARMONY AND RHYTHM IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF WESTERN ART MUSIC IMPLICATIONS FOR A PHILOSOPHY OF MUSIC HISTORY A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment o f the Requirements fo r the Degree Master of Arts by Wolfgang Hans Martin Stefani August 1981 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE PSYCHO-PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF VOLUME, PITCH, HARMONY AND RHYTHM IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF WESTERN ART MUSIC IMPLICATIONS FOR A PHILOSOPHY OF MUSIC HISTORY A Thesis present in partial fulfillment of the requirements fo r the degree Master of Arts by Wolfgang Hans Martin Stefani APPROVAL BY THE COMMITTEE: Paul E. -

RCA LHMV 1 His Master's Voice 10 Inch Series

RCA Discography Part 33 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA LHMV 1 His Master’s Voice 10 Inch Series Another early 1950’s series using the label called “His Master’s Voice” which was the famous Victor trademark of the dog “Nipper” listening to his master’s voice. The label was retired in the mid 50’s. LHMV 1 – Stravinsky The Rite of Spring – Igor Markevitch and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 2 – Vivaldi Concerto for Oboe and String Orchestra F. VII in F Major/Corelli Concerto grosso Op. 6 No. 4 D Major/Clementi Symphony Op. 18 No. 2 – Renato Zanfini, Renato Fasano and Virtuosi di Roma [195?] LHMV 3 – Violin Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2 (Bartok) – Yehudi Menuhin, Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 4 – Beethoven Concerto No. 5 in E Flat Op. 73 Emperor – Edwin Fischer, Wilhelm Furtwangler and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 5 – Brahms Concerto in D Op. 77 – Gioconda de Vito, Rudolf Schwarz and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1954] LHMV 6 - Schone Mullerin Op. 25 The Maid of the Mill (Schubert) – Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Gerald Moore [1/55] LHMV 7 – Elgar Enigma Variations Op. 36 Wand of Youth Suite No. 1 Op. 1a – Sir Adrian Boult and the London Philharmonic Orchestra [1955] LHMV 8 – Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F/Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D – Harold Jackson, Gareth Morris, Herbert Sutcliffe, Manoug Panikan, Raymond Clark, Gerraint Jones, Edwin Fischer and the Philharmonia Orchestra [1955] LHMV 9 – Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C Minor Op.