Revisioning Person-Centred Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying Gabriel Marcel's Thought in Social

Marcel Studies, Vol. 1, Issue No. 1, 2016 Applying Gabriel Marcel’s Thought in Social Work Practice MARK GRIFFITHS, School of Health and Social Development, Deakin University Geelong Waterfront Campus, Victoria 3217, Australia. [email protected] Abstract: Gabriel Marcel‟s thought is applied to social work practice in the fields of restorative justice conferencing for young people and working with male perpetrators of family violence. Existential ideas have helped to shape social work from its beginnings, but with the one exception of Jim Lantz, the philosophical ideas of Gabriel Marcel have not been utilised. I argue that Marcel‟s existential concepts speak to the vocation of social work and the challenge to fully participate in the world in the 21st century. These concepts include the concrete value of people‟s lived experience, which includes elements of mystery and problem, the importance of being accessible and present to others, and seeking to respond to the cry of the world heard in our communities. Introduction Gabriel Marcel‟s thought is useful to social workers and to some of the key challenges facing the profession in the 21st century. Social workers are re-examining their vocation, moving beyond a social maintenance and functional role, focusing on the importance of relationship building in the attempt to heal social harms, and are embracing a holistic approach to concrete social problems that incorporates a spiritual perspective and a participatory understanding of human existence. In this article, Marcel‟s thought is applied to working in a men‟s behaviour change group addressing family violence, and in facilitating a restorative justice conference with a young offender and his victim, together with their supporters and other professionals. -

Revisioning Person-Centred Research

Edinburgh Research Explorer Revisioning person-centred research Citation for published version: Hilton, J & Prior, S 2018, Revisioning person-centred research. in M Bazzano (ed.), Revisioning Person- Centred Therapy: Theory and Practice of a Radical Paradigm. Routledge, London, pp. 277-287. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351186797 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.4324/9781351186797 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Revisioning Person-Centred Therapy Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge in Re-Visioning Person-Centred Therapy: Theory and Practice of a Radical Paradigm on 27/06/2018, available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781351186780 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Re-visioning Person-Centred Research Jo Hilton and Seamus Prior Abstract Students of the person centred approach frequently comment on how there is something nourishing and inspiring about reading the work of Carl Rogers. I/we would argue, in common with Bondi and Fewell (2016) and Canavan and Prior (2016) that this is no accident. -

Trabajo Investigativo Sobre Psicólogas Pioneras: Julia Jessie Taft (EEUU 1882-1960)

Alumnas de 1º de Psicología de los Grupos Profesora Ana Guil Trabajo investigativo sobre psicólogas pioneras: Julia Jessie Taft (EEUU 1882-1960) Eugenia de Gabriel Sánchez ([email protected]) Alicia Cabrera Torres ([email protected]) Clara Díaz Gutiérrez ([email protected]) Índice • Biografía • Tesis • Carrera profesional • Teoria Social • Bibliografía Biografía • Nació en 1882 en Dubuque, Iowa. • Falleció en 1960 en Flourtown, Pensilvania. • Estudió en la Universidad de Drake en Des Moines, Iowa donde obtuvo un título de Bachillerato con 22 años • Al año siguiente, estudió en la Universidad de Chicago y recibió un Ph.B • Durante los 4 años siguientes fue profesora en su antigua escuela de secundaria en Des Moines Biografía • Posteriormente, realizó su trabajo de posgrado en la Universidad de Chicago • Trabajo con George H. Mead gracias a una beca, quien fue su asesor de tesis —> PRAGMATISMO AMERICANO • Allí conoció a Virginia P. Robinson, su compañera de vida. Biografía • Trabajó con Otto Rank, discípulo de Freud. • Taft empezó siendo paciente suyo, pero pasó a ser su alumna y amiga, y con los años su exponente, su ejemplo. • Se conocieron en 1924, en una reunión de la American Psychoanalytic Association en Atlantic City, donde él impartió una conferencia sobre The Trauma Of Birth, libro suyo. • Este hecho impresionó a Taft y se incorporó a su grupo en 1927. • Posteriormente, Rank introdujo la idea de la terapia de voluntad, definida por ella como “fuerza creadora original”, “voluntad para explicar la conducta -

Person-Centred Therapy Vs. Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy

PERSON-CENTRED THERAPY VS. RATIONAL EMOTIVE BEHAVIOUR THERAPY The purpose of this paper is to present a brief comparison of the approach to psychotherapy of Carl Rogers and Albert Ellis. I have selected Albert Ellis for comparative purposes since he was one of the other therapists participating with Rogers in the film “Three Approaches to Psycotherapy” , made in 1964, centering on interviews with the client “Gloria”. Person-Centered Therapy Rogers first formulated the essentials of Person-Centered Therapy (PCT), an approach to helping individuals and groups in conflict, in 1940. At the time it was a revolutionary hypothesis that a self-directed growth process would follow the provision and reception of a particular kind of relationship characterized by genuineness, non-judgmental caring, and empathy. Its most fundamental and pervasive concept is trust. The foundation of Rogers’ approach is a human being’s actualizing tendency towards the realization of his or her full potential; which he described as a formative tendency observable in the movement toward 134greater order, complexity and interrelatedness. The person-centered approach is built on trust that individuals and groups can set their own goals and monitor their own progress towards them. It assumes that the clients can be trusted to select their own therapist, choose the frequency and length of their therapy, talk or be silent, decide what needs to be explored, achieve their own insights, and be the architects of own lives. Moreover, groups can be trusted to develop processes right for them and to resolve conflicts in the group. In Person-Centered Therapy, the therapist provides continuous and constant empathy for the client's perceptions, meanings and feelings. -

Nondirective Counseling

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Social Sciences 140 Nondirective Counseling Effects of Short Training and Individual Characteristics of Clients BY ERIK RAUTALINKO ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2004 ! "#$ % & % % ' ( ) * *( + , -( !( . &( -%% % ) & / . % . ( 0 ( ! ( 12 ( ( /3 45$$!51 "15! & * & 6 % ( / % % . + & 7 & % % & & ( ) * %* * % & & ( ) % %% % & & 8 * %% % ( ) 7 5 9' /5///: ( / ' / * +% & 9+;< , % &: , % % & & ( ) & +; , * % &( ) * * %% ( / ' // & * % % +; & % & ( 0 & , 7 % * & & % =& % =& * ( / ' /// * & 7 +; 5 7 * =& * %% , & ( +; & * 5 7 =&6 & * , & ( / & %% , & 8 % % , % & , & ( & % & 5 7 & , & ! " #! $% &''(! ! )*(&+' ! > -, + , ! / 25?!4 /3 45$$!51 "15! # ### 5!$$ 9 #@@ (,(@ A B # ### 5!$$: LIST OF PAPERS Paper I: Rautalinko, E., & Lisper, H.-O. (2004). Effects of training reflective listening in a corporate setting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 18, 281-299. Paper II: Rautalinko, E., Lisper, H.-O., & Ekehammar, B. (2004). Training reflective listening -

Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship

Éisteach Volume 14 l Issue 2 l Summer 2014 Carl Rogers, Martin Buber, and Relationship by Ian Woods Abstract This article gives a brief biographical sketch of Carl Rogers (1902-1987) and Martin Buber (1878-1965) and summarises their respective views on relationship before outlining the public dialogue in which they engaged in 1957. The outline concentrates on the part of the dialogue dealing with the therapist-client relationship and indicates some of the essential points of the exchanges between the two men, drawing out their differing perspectives. As well as commenting also on Brian Thorne’s view of the dialogue, the author’s own views are indicated both on the content of the dialogue and its implications for practice. The two men. assumption of power in 1933. He 1937 was published in English as “I arl Rogers and Martin Buber met had by then become the leading and Thou”. Cin public dialogue on 18 April interpreter of Hasidism and Jewish Following an enforced departure 1957 in the University of Michigan, mysticism and had begun what from Germany in 1938 (the same U.S.A. There was an age difference became a lifetime’s large literary year as Freud’s move to England), of 24 years between them, Buber output including more than sixty Buber became professor at the being 79 and Rogers 55 at the volumes on religious, philosophical Hebrew University of Jerusalem until time. The difference in background and related subjects. In 1923 he his retirement in 1951. During the between the two men was even more published “Ich und Du” which in early years of the State of Israel, he considerable. -

Winds of Change for Client-Centered Counseling

WINDS OF CHANGE FOR CLIENT-CENTERED COUNSELING C. H. PATTERSON Humanistic Education and Development, 1993, 31, 130-133. In Understanding Psychotherapy: Fifty Years of Client-Centered Theory and Practice. PCCS Books, 2000. The winds of change they are ablowing. Client-centered counseling should be growing. The winds of change are blowing on client-centered counseling (among others, Cain, 1986, 1989a, 1989b, 1989c, 1990; Combs, 1988; Sachse, 1989; Sebastian, 1989). In the 3 years following the death of Carl Rogers, many were expressing dissatisfaction with ''traditional'' or "pure'' client-centered counseling and were engaged in trying to supplement it, extend it, and modify it. The basic complaint seems to be that the counselor conditions specified by Rogers (1957) are not sufficient. Tausch, at the International Conference on Client-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapy in Belgium in 1988, is quoted by Cain (1989c) as stating that client-centered therapy, in its pure form, is not effective for some clients and insufficient for others. Cain (1989c) commented on Gendlin's (1988) plenary address at the Belgium conference, noting that "some consider Gendlin's work a creative extension of client-centered therapy, while others contend that experiential therapy is simply incompatible with the theory and practice of client-centered therapy" (pp. 5-6). Brodley (1988) belongs to the latter group, judging from her paper at the same conference "Client-Centered and Experiential-Two Different Therapies.'' Cain (1989c) reported that Gendlin said he -

Personal Construct Psychology

WHAT WE EXPECT WHAT WE GET WHAT WE GET How did we get to this…and how do we recover? NEW AND IMPROVED THEORY? OR….. SAME OLE’ THING…WITH A NEW LOOK. Ecclesiastes 1:9 Structure of Sanctuary “Given the evidence that treatments are about equally effective, that treatments WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT delivered in clinical settings are PSYCHOTHERAPY? AND WHAT IS THERE LEFT TO DEBATE? effective (and as effective as that BRUCE E. WAMPOLD, PH.D., provided in clinical trials), that ABPPZAC E. IMEL, PH.D. 2018 the manner in which treatments are provided are much more important than which treatment is provided, mandating particular treatments seems illogical.” “THE DEVELOPMENT OF A THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP IS THE MOST ACCURATE INDICATOR OF A POSITIVE OUTCOME.” - J. ERIC GENTRY CARL ROGERS • January 1902-February 1987 • Person Centered Therapy • Unconditional Positive Regard + Congruence = Person Centered Treatment “I am not perfect…but I am enough.” PAUL D. MACLEAN • May 1913-December 2007 • Triune Brain • Three Distinct Brain Segments: Protoreptilian Paleomammalian Neomammalian “An interest in the brain requires no justification other than a curiosity to know why we are here, what we are doing here, and where we are going.” THE TRIUNE BRAIN Reptilian Brain Limbic Brain Neocortex ERIK ERIKSON • June 1902-May 1994 • Stages of Development • Development happens in stages with spectrum type “virutes” “Hope is both the earliest and the most indispensable virtue inherent in the state of being alive.” STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT • Traumatic Reenactment regresses an -

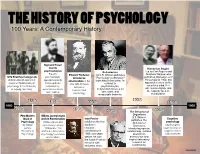

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

Pioneras Del Trabajo Social

Pioneras del Trabajo Social Exposición bibliográfica Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y del Trabajo Del 7 al 31 de enero de 2014 Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y del Trabajo Biblioteca Universidad de Zaragoza C/ Violante de Hungría, 23 50009 Zaragoza (España) Realizado por: Miguel Miranda Aranda Jesús Gracia Ostáriz Rosa Pueyo Moy Página Web: http://biblioteca.unizar.es/biblio.php?id=20 Correo Electrónico: [email protected] SUMARIO Introducción ....................................................................................... 3 Catálogo bibliográfico ........................................................................ 5 Introducción La Biblioteca de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales y del Trabajo hace años que viene recopilando obras de las pioneras del Trabajo Social y de autores que, aun sin ser parte de la profesión, tuvieron algún papel en su nacimiento y desarrollo. No sin esfuerzo, en los últimos años la Biblioteca de la Facultad ha conseguido ir acumulando un número importante de obras, a menudo difíciles de conseguir. El esfuerzo merece la pena porque se trataba de conseguir que alumnos y profesores puedan tener accesible lo que escribieron las pioneras, convertidas ya en nuestros clásicos. Cualquier disciplina necesita de estas referencias y no sólo por motivos históricos, sino para construir su propia identidad. De la misma manera que no hay psicólogos que no hayan leído a sus clásicos, ni sociólogos o antropólogos que no hayan leído a los suyos, tampoco debería haber trabajadores sociales que ignoren lo que supusieron, en su momento y todavía hoy, las aportaciones de Mary Richmond, de Jane Addams, de Gordon Hamilton, de Octavia Hill, de Virginia Robinson, de Jessie Taft, Charlotte Towle, así como por qué citamos a los Web o a Edward T. -

The Human Being: J.L. Moreno's Vision in Psychodrama

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY, VOL. 8, NO. 1, MARCH 2003, pp. 31 – 36 The human being: J.L. Moreno’s vision in psychodrama NORBERT APTER Institut ODeF, 65, rue de Lausanne, CH – 1202, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract Integrating two different psychotherapeutic approaches is more and more frequent among psychologists. Psychodrama is often chosen as one. In order to be coherent and efficient, serious attention must be paid to verifying the compatibility of the two chosen approaches when integrating them (even partly), especially in terms of their vision of the human being. In order to facilitate this necessary verification, Norbert Apter reviews here Moreno’s psychodrama vision of the human being: a relational being, the spontaneity and creativity of which form the pillars enabling him to actualize his interactions and the interiorized roles on which he relies. Introduction Many psychologists throughout the world rely on psychodrama and its tools. There are many non-psychodramatists who have chosen to integrate only certain aspects of the method into their own school of psychotherapy (psychoanalysis, Jungian analysis, Adlerian analysis, family therapy, cognitive therapy, behavioural therapy, etc . .). (Blatner & Blatner, 1988, p. 2) list some 13 major therapeutic currents in which professionals chose to include some elements of psychodrama as a tool. The technique of psychodrama according to a given vision of the human being1 was developed by the psychiatrist, Jacob Levy Moreno (1889 – 1974). However, visions of the human being underlying various implementations of psychodrama are diverse and varied. Many people use psychodrama based on an approach that differs from Moreno’s vision of the human being. -

Healthy Personality

HEALTHY PERSONALITY Presented by CONTINUING PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATION 7.2 CONTACT HOURS “I wanted to prove that human beings are capable of something grander than war and prejudice and hatred.” Abraham Maslow, Psychology Today, 1968, 2, p.55. Course Objective Learning Objectives The purpose of this course is to provide an Upon completion, the participant will understand understanding of the concept of healthy personality. the nature, motivation, and characteristics of the Seven theorists offer their views on the subject, healthy personality. Seven influential including: Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, Erich psychotherapists-theorists examine the concept Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung, Viktor of healthy personality allowing the reader to Frankl, and Fritz Perls. integrate these principles into his or her own life. Accreditation Faculty Provider approved by the California Board of Neil Eddington, Ph.D. Registered Nursing, Provider # CEP 14008, for Richard Shuman, MFT 7.2 Contact Hours. In accordance with the California Code of Regulations, Section 2540.2(b) for licensed vocational nurses and 2592.2(b) for psychiatric technicians, this course is accepted by the Board of Vocational Nursing and Psychiatric Technicians for 7.2 contact hours of continuing education credit. Mission Statement Continuing Psychology Education provides the highest quality continuing education designed to fulfill the professional needs and interests of nurses. Resources are offered to improve professional competency, maintain knowledge of the latest advancements, and meet continuing education requirements mandated by the profession. Copyright © 2006 Continuing Psychology Education 1 Continuing Psychology Education P.O. Box 9659 San Diego, CA 92169 FAX: (858) 272-5809 phone: 1 800 281-5068 www.texcpe.com HEALTHY PERSONALITY INTRODUCTION personality offered by Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, Erich Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung, Viktor Frankl, and Fritz The study of healthy personality was ignored for a long time Perls.