REPTILES; PREDATORS Aild AMPHIBIANS and BIRDS Cook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rodondo Island

BIODIVERSITY & OIL SPILL RESPONSE SURVEY January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF PRIMARY INDUSTRIES, PARKS, WATER AND ENVIRONMENT RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 RODONDO ISLAND BASS STRAIT Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015 NATURE CONSERVATION REPORT SERIES 15/04 Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Tasmania. © Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment ISBN: 978-1-74380-006-5 (Electronic publication only) ISSN: 1838-7403 Cite as: Carlyon, K., Visoiu, M., Hawkins, C., Richards, K. and Alderman, R. (2015) Rodondo Island, Bass Strait: Biodiversity & Oil Spill Response Survey, January 2015. Natural and Cultural Heritage Division, DPIPWE, Hobart. Nature Conservation Report Series 15/04. Main cover photo: Micah Visoiu Inside cover: Clare Hawkins Unless otherwise credited, the copyright of all images remains with the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced for study, research or training purposes subject to an acknowledgement of the source and no commercial use or sale. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Branch Manager, Wildlife Management Branch, DPIPWE. Page | 2 RODONDO ISLAND – Oil Spill & Biodiversity Survey, January 2015 SUMMARY Rodondo Island was surveyed in January 2015 by staff from the Natural and Cultural Heritage Division of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE) to evaluate potential response and mitigation options should an oil spill occur in the region that had the potential to impact on the island’s natural values. Spatial information relevant to species that may be vulnerable in the event of an oil spill in the area has been added to the Australian Maritime Safety Authority’s Oil Spill Response Atlas and all species records added to the DPIPWE Natural Values Atlas. -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

Draft Animal Keepers Species List

Revised NSW Native Animal Keepers’ Species List Draft © 2017 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to their specific needs. All content in this publication is owned by OEH and is protected by Crown Copyright, unless credited otherwise. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), subject to the exemptions contained in the licence. The legal code for the licence is available at Creative Commons. OEH asserts the right to be attributed as author of the original material in the following manner: © State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2017. Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59 Goulburn Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A290, -

Reptiles of the Wet Tropics

Reptiles of the Wet Tropics The concentration of endemic reptiles in the Wet Tropics is greater than in any other area of Australia. About 162 species of reptiles live in this region and 24 of these species live exclusively in the rainforest. Eighteen of them are found nowhere else in the world. Many lizards are closely related to species in New Guinea and South-East Asia. The ancestors of two of the resident geckos are thought to date back millions of years to the ancient super continent of Gondwana. PRICKLY FOREST SKINK - Gnypetoscincus queenlandiae Length to 17cm. This skink is distinguished by its very prickly back scales. It is very hard to see, as it is nocturnal and hides under rotting logs and is extremely heat sensitive. Located in the rainforest in the Wet Tropics only, from near Cooktown to west of Cardwell. RAINFOREST SKINK - Eulamprus tigrinus Length to 16cm. The body has irregular, broken black bars. They give birth to live young and feed on invertebrates. Predominantly arboreal, they bask in patches of sunlight in the rainforest and shelter in tree hollows at night. Apparently capable of producing a sharp squeak when handled or when fighting. It is rare and found only in rainforests from south of Cooktown to west of Cardwell. NORTHERN RED-THROATED SKINK - Carlia rubrigularis Length to 14cm. The sides of the neck are richly flushed with red in breeding males. Lays 1-2 eggs per clutch, sometimes communally. Forages for insects in leaf litter, fallen logs and tree buttresses. May also prey on small skinks and own species. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Australia Part 2 2019 Oct 22, 2019 to Nov 11, 2019 John Coons & Doug Gochfeld For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Water is a precious resource in the Australian deserts, so watering holes like this one near Georgetown are incredible places for concentrating wildlife. Two of our most bird diverse excursions were on our mornings in this region. Photo by guide Doug Gochfeld. Australia. A voyage to the land of Oz is guaranteed to be filled with novelty and wonder, regardless of whether we’ve been to the country previously. This was true for our group this year, with everyone coming away awed and excited by any number of a litany of great experiences, whether they had already been in the country for three weeks or were beginning their Aussie journey in Darwin. Given the far-flung locales we visit, this itinerary often provides the full spectrum of weather, and this year that was true to the extreme. The drought which had gripped much of Australia for months on end was still in full effect upon our arrival at Darwin in the steamy Top End, and Georgetown was equally hot, though about as dry as Darwin was humid. The warmth persisted along the Queensland coast in Cairns, while weather on the Atherton Tablelands and at Lamington National Park was mild and quite pleasant, a prelude to the pendulum swinging the other way. During our final hours below O’Reilly’s, a system came through bringing with it strong winds (and a brush fire warning that unfortunately turned out all too prescient). -

Venemous Snakes

WASAH WESTERN AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY of AMATEUR HERPETOLOGISTS (Inc) K E E P I N G A D V I C E S H E E T Venomous Snakes Southern Death Adder (Acanthophis Southern Death antarcticus) – Maximum length 100 cm. Adder Category 5. Desert Death Adder (Acanthophis pyrrhus) – Acanthophis antarcticus Maximum length 75 cm. Category 5. Pilbara Death Adder (Acanthophis wellsi) – Maximum length 70 cm. Category 5. Western Tiger Snake (Notechis scutatus) - Maximum length 160 cm. Category 5. Mulga Snake (Pseudechis australis) – Maximum length 300 cm. Category 5. Spotted Mulga Snake (Pseudechis butleri) – Maximum length 180 cm. Category 5. Dugite (Pseudonaja affinis affinis) – Maximum Desert Death Adder length 180 cm. Category 5. Acanthophis pyrrhus Gwardar (Pseudonaja nuchalis) – Maximum length 100 cm. Category 5. NOTE: All species listed here are dangerously venomous and are listed as Category 5. Only the experienced herpetoculturalist should consider keeping any of them. One must be over 18 years of age to hold a category 5 license. Maintaining a large elapid carries with 1 it a considerable responsibility. Unless you are Pilbara Death Adder confident that you can comply with all your obligations and licence requirements when Acanthophis wellsi keeping dangerous animals, then look to obtaining a non-venomous species instead. NATURAL HABITS: Venomous snakes occur in a wide variety of habitats and, apart from death adders, are highly mobile. All species are active day and night. HOUSING: In all species listed except death adders, one adult (to 150 cm total length) can be kept indoors in a lockable, top-ventilated, all glass or glass-fronted wooden vivarium of Western Tiger Snake at least 90 x 45 cm floor area. -

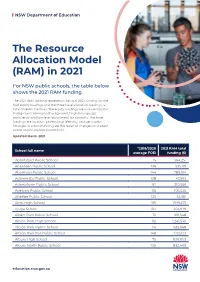

The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021

NSW Department of Education The Resource Allocation Model (RAM) in 2021 For NSW public schools, the table below shows the 2021 RAM funding. The 2021 RAM funding represents the total 2021 funding for the four equity loadings and the three base allocation loadings, a total of seven loadings. The equity loadings are socio-economic background, Aboriginal background, English language proficiency and low-level adjustment for disability. The base loadings are location, professional learning, and per capita. Changes in school funding are the result of changes to student needs and/or student enrolments. Updated March 2021 *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Abbotsford Public School 15 364,251 Aberdeen Public School 136 535,119 Abermain Public School 144 786,614 Adaminaby Public School 108 47,993 Adamstown Public School 62 310,566 Adelong Public School 116 106,526 Afterlee Public School 125 32,361 Airds High School 169 1,919,475 Ajuga School 164 203,979 Albert Park Public School 111 251,548 Albion Park High School 112 1,241,530 Albion Park Public School 114 626,668 Albion Park Rail Public School 148 1,125,123 Albury High School 75 930,003 Albury North Public School 159 832,460 education.nsw.gov.au NSW Department of Education *2019/2020 2021 RAM total School full name average FOEI funding ($) Albury Public School 55 519,998 Albury West Public School 156 527,585 Aldavilla Public School 117 681,035 Alexandria Park Community School 58 1,030,224 Alfords Point Public School 57 252,497 Allambie Heights Public School 15 -

Phylogeography and Population Genetic Structure of the Ornate Dragon Lizard, Ctenophorus Ornatus

Phylogeography and Population Genetic Structure of the Ornate Dragon Lizard, Ctenophorus ornatus Esther Levy*, W. Jason Kennington, Joseph L. Tomkins, Natasha R. LeBas Centre for Evolutionary Biology, School of Animal Biology, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia Abstract Species inhabiting ancient, geologically stable landscapes that have been impacted by agriculture and urbanisation are expected to have complex patterns of genetic subdivision due to the influence of both historical and contemporary gene flow. Here, we investigate genetic differences among populations of the granite outcrop-dwelling lizard Ctenophorus ornatus, a phenotypically variable species with a wide geographical distribution across the south-west of Western Australia. Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequence data revealed two distinct evolutionary lineages that have been isolated for more than four million years within the C. ornatus complex. This evolutionary split is associated with a change in dorsal colouration of the lizards from deep brown or black to reddish-pink. In addition, analysis of microsatellite data revealed high levels of genetic structuring within each lineage, as well as strong isolation by distance at multiple spatial scales. Among the 50 outcrop populations’ analysed, non-hierarchical Bayesian clustering analysis revealed the presence of 23 distinct genetic groups, with outcrop populations less than 4 km apart usually forming a single genetic group. When a hierarchical analysis was carried out, almost every outcrop was assigned to a different genetic group. Our results show there are multiple levels of genetic structuring in C. ornatus, reflecting the influence of both historical and contemporary evolutionary processes. They also highlight the need to recognise the presence of two evolutionarily distinct lineages when making conservation management decisions on this species. -

Death Adders {Acanthophis Laevis Complex) from the Island of Ambon

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Herpetozoa Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 19_1_2 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kuch Ulrich, McGuire Jimmy A., Yuwono Frank Bambang Artikel/Article: Death adders (Acanthophis laevis complex) from the island of Ambon (Maluku, Indonesia) 81-82 ©Österreichische Gesellschaft für Herpetologie e.V., Wien, Austria, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at SHORT NOTE HERPETOZOA 19(1/2) Wien, 30. Juli 2006 SHORT NOTE 81 O. & PINTO, I. & BRUFORD, M. W. & JORDAN, W. C. & NICHOLS, R. A. (2002): The double origin of Iberian peninsular chameleons.- Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, London; 75: 1-7. PINHO, C. & FER- RAND, N. & HARRIS, D. J. (2006): Reexamination of the Iberian and North African Podarcis phylogeny indi- cates unusual relative rates of mitochondrial gene evo- lution in reptiles.- Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolu- tion, Chicago; 38: 266-273. POSADA, D. &. CRANDALL, K. A. (1998): Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution- Bioinformatics, Oxford; 14: 817-818. SWOFFORD, D. L. (2002): PAUP*. Phylogenetic analy- sis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0. Sinauer Associates, Uderland, Massachusetts. WADK, E. (2001): Review of the False Smooth snake genus Macroprotodon (Serpentes, Colubridae) in Algeria with a description of a new species.- Bulletin National Fig. 1 : Adult death adder (Acanthophis laevis com- History Museum London (Zoology), London; 67 (1): plex) from Negeri Lima, Ambon (Central Maluku 85-107. regency, Maluku province, Indonesia). Photograph by U. KUCH. KEYWORDS: mitochondrial DNA, cyto- chrome b, Macroprotodon, evolution, systematics, Iberian Peninsula, North Africa SUBMITTED: April 1,2005 and Bali by the live animal trade. -

Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd

Jemena Northern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd Northern Gas Pipeline Draft Environmental Impact Statement CHAPTER 12 – MATTERS OF NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SIGNIFICANCE Public August 2016 MATTERS OF NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL SIGNIFICANCE — 12 Contents 12. Matters of National Environmental Significance ............................................................. 12-1 12.1 Overview .................................................................................................................... 12-1 12.2 Relevant MNES ......................................................................................................... 12-2 12.2.1 Threatened species ............................................................................................ 12-2 12.2.2 Plains Death Adder (Acanthophis hawkei) ........................................................ 12-13 12.2.3 Carpentarian Antechinus (Pseudantechinus mimulus) ...................................... 12-18 12.2.4 Threatened species conclusion ......................................................................... 12-23 12.3 Risk assessment ...................................................................................................... 12-23 12.3.1 Potential impacts .............................................................................................. 12-23 12.3.2 Planning ............................................................................................................ 12-24 12.3.3 Construction .................................................................................................... -

Index to Scientific Names of Amphibians and Reptiles for Volume 43 (2008)

Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 43(12):204-206, 2008 Index to Scientific Names of Amphibians and Reptiles for Volume 43 (2008) January 1-16 April 57-72 July 109-124 October 157-172 February 17-32 May 73-92 August 125-140 November 173-188 March 33-56 June 93-108 September 141-156 December 189-208 Acanthophis 24 constrictor 65, 66, 120 Cordylus cataphractus 88 Diplodactylus antarcticus 1, 142 constrictor 96 Craugastor 104 steindachneri 24 hawkei 24 imperator 96 fitzingeri 169 taenicauda 24 praelongus 169 occidentalis 96 mimus 169 Draco 49, 50 rugosus 24 Bogertophis 43 noblei 169 Egernia woolfi 24 Boiga irregularis 23, 63, 107 Crocodylus cunninghami 4, 142 Acanthosaura crucigera 50 Bothrops 157, 158 rhombifer 50 frerei 23 Acris 73 jararacussu 157 siamensis 48 hosmeri 24 crepitans 19, 20, 43, 73 Bradypodion melanocephalum 139 Crotalinus kingii 24 blanchardi 73 Buergeria japonica 105 catenatus 106 stokesii 24 crepitans 73, 78 Bufo 42, 73 viridis 106 Elaphe 42, 43, 75 Acrochordus javanicus 50 americanus 17 Crotalus 74 carinata 100, 101 Adelphobates captivus 89 boreas boreas 90 atrox 88, 200 mandarina 100, 101 Afroedura 52 celebensis 134 ericsmithi 123 obsoleta 20, 137 Agkistrodon marinus 23, 50, 66 horridus 74, 79 porphyracea 100 contortrix 76 terrestris 62 lannomi 123 spiloides 75 piscivorus 76, 106 Bungarus 27 massasaugus 106 taeniura 100 leucostoma 90 Caiman crocodilus 76 messasaugus 106 vulpina 75 Ahaetulla prasina 50 Calloselasma rhodostoma 49, 50 mitchellii 29, 202 Eleutherodactylus 69, 104 Alligator mississippiensis 76, 120 Cantoria violacea